In anticipation of his upcoming performance as Father Bartholomew Mary, Gideon Jacobs speaks with Trevor Paglen on how humanity’s ancient anxieties around visual representation are taking on new forms

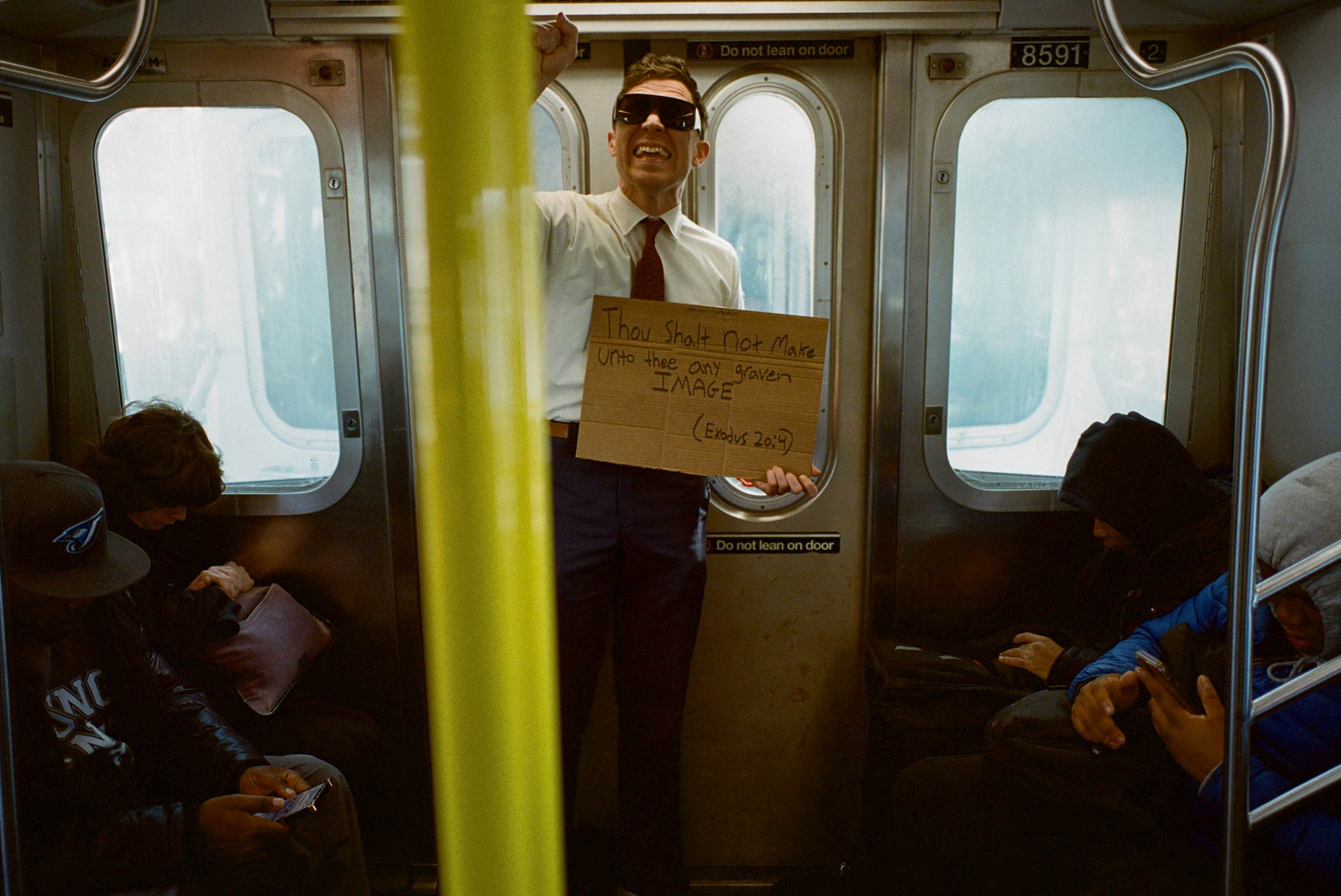

Tomorrow, April 18th, writer and performer Gideon Jacobs will premiere his new show Images at EARTH, the New York arts space run by Annika Kuhlmann, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, and Dean Kissick. The performance marks the start of a sold-out, three-show run. In it, he embodies Father Bartholomew Mary, a blind Southern preacher and Second Commandment fundamentalist whose sermons thunder against the idolization of imagery—old or new, divine or digital. As AI renders reality increasingly fluid, Images arrives as both a cautionary parable and philosophical provocation, with Father Bartholomew serving as a vehicle to explore our increasingly fraught relationship with images.

Ahead of this debut, Jacobs met with artist Trevor Paglen, known for his work examining surveillance systems and power structures, to discuss the theological, philosophical, and cultural implications of our image-saturated world. Their conversation resonates with Czech philosopher Vilém Flusser’s prescient observations about photography’s role in reshaping human consciousness. “The photograph is a kind of interface between us and the world,” Flusser wrote in his 1983 work, Towards a Philosophy of Photography. “We no longer experience the world directly but through photographs; we experience, know, evaluate and act upon it as a function of photographs.”

The artists examine how humanity’s relationship with images has evolved from ancient religious prohibitions to our current crisis of visual authenticity. Their discussion echoes Flusser’s warning that technical images create a “magical consciousness” that can obscure rather than reveal reality—a concern that takes on new urgency in our AI-generated visualscape.

Gideon Jacobs: I’m trying to remember how much I’ve told you about the performance. Basically, Dean Kissick saw a clip of me performing as this character—a second commandment fundamentalist preacher who appears in a novel I’ve been working on. This character is a way for me to exercise, cathartically, some of my more iconoclastic anxieties about our species’ relationship to images. I personally don’t think iconoclasm is ever really the viable way forward—I don’t think it’s ever the right mode. Nobody imbues the image with more power than the image breaker or the censor. So this character allows me to get this part of my brain out there in a campy, absurd, hyperbolic way.

I’d be curious to hear, Trevor, how you hold the iconoclastic versus iconophilic parts of your brain. How would you classify your relationship to images at this point in your life?

Trevor Paglen: I feel like images are like goblins, in the sense that you want them to do things, but then they’re always going to do what they’re going to do. They’re just slippery fuckers, you know?

I don’t mean that in some kind of Neo-materialist way, but just in the sense that they’re extremely curious objects that are many things simultaneously and that are indefinable—and that indefinability changes over time, including for the same image. Their variability is also incredibly specific to the larger set of relationships they’re embedded within.

“I feel like images are like goblins, in the sense that you want them to do things, but then they’re always going to do what they’re going to do. They’re just slippery fuckers, you know?”

I guess I think about images in so many ways simultaneously that they’re just really hard to pin down. On one day, an image can have some kind of iconic status; the next day it can be a means of commodification or industrialization; and on the next day, it can be a neural trigger. What about you? Where is this anxiety coming from for you?

Gideon: That’s almost a question for me and my therapist—to trace where it’s coming from. The truth is, I’ve been orbiting this concern with our relationship to images my whole adult life. My first job was for Magnum Photos. I was there for five years, became a big part of my early professional life, deeply involved and interested in that organization. That’s obviously an organization founded on the image copyright and that sort of carried the torch of the power of images in some very old-fashioned way. But then, oftentimes, they were on the front lines of questions about the veracity of imagery.

Trevor: Interesting, because Magnum is very specific. It’s photography, which is a subset of images itself.

Gideon: It’s documentary, which is a subset of that subset.

Trevor: It’s a very specific genre, and it’s a genre I’ve been thinking about a lot. I’m wondering, how has your anxiety around images in general, and that mode of photography in particular, been complicated by the generative AI turn?

Gideon: Well, it’s funny, I quit my job at Magnum in my mid-to-late 20s, partially because I wanted to write full-time. But I think it’s telling that the first project I did after I left was a fake road trip on Instagram. It sounds silly now, but I thought, “What do people do after they quit a job and are in a searching moment? They drive across the country.” I decided to just do that on Instagram.

I drew a route on an atlas, and each day I would find a photo that was geo-tagged in whatever town I was supposed to be in, screenshot it and post it, then write an anecdote about “my day” taking that photo. I did this for almost a month. That was my reaction to leaving Magnum, this bastion of truth in documentary photography

This anxiety about images has been with me for ten years now. I’m 35. I think it has psychological roots—I acted professionally as a kid, and it doesn’t take a genius analyst to see that maybe a childhood where images of me were prioritized over the actual referent might have shaped my relationship with images.

Trevor: So you go from creating imaginary images that come to define you in this larger sense, and where do you go from there? Magnum, right?

Gideon: Exactly. I have this micro push-and-pull with images in my life. And humanity’s push-and-pull with images on the macro scale is a big part of our story. You and I talked previously about theological relationships with imagery in old cosmic structures—the Protestant Reformation and the Beeldenstorm, which I think literally means “image storm”—drunken Protestants in Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands going into Catholic churches and breaking things. And we talked about periods of iconoclasm in Byzantium.

When you said that images change all the time for you, to me that means you cannot make a fixed image. Your relationship to images defies imagistic stability.

Trevor: Yeah, completely. Having said that, there’s a macro question right now that your essay about imagery in the age of Trump articulates beautifully. If we look at this big history, the Second Commandment—depending on the translation—is either a ban on images that become objects of worship, or just all images. It seems you can read it both ways.

The strong version means a ban on all images; the weak version is a ban on representations of the divine. Both seem interconnected, and I suspect that philosophically, that’s the source of confusion. It’s difficult to disentangle the image of the divine from the image of the quotidian.

What’s the point of the Second Commandment? The strong version seems to imply that the transcendental signified must be located in a place that is beyond images, beyond language. So the divine must be in its own form, conveyed to you by ritual or liturgy—something non-imagistic.

The idea I’m trying out is whether photography upended that. As a genre, in the mid-19th century, people like Arago, or looking at the Magnum documentary tradition—photography held out the promise of having some kind of stable relationship to reality through images. Whether there’s a quasi-theological claim being implicitly made there.

I wonder if the advent and proliferation of photography created a technological a priori that assumes some relationship between images and the world, or between observation and the world. It was part of this larger grounding of reality in empiricism. And whether that becomes upended in an age where you’re able to make photographic-looking images of whatever you want—creating this weird, perverted form of iconography that blends photography with iconology.

Gideon: I love that, Trevor. I think you’re getting at something I was excited about when I first met you. As fearful as I was about how quickly these AI technologies are growing, there was a part of me excited about AI undoing that moment with Arago and daguerreotype—the moment when Arago said, “We will be able to map the night sky,” connecting astronomy, photography, mapping, and classification.

People who are really interested in photography know that talking about truth in photographs is a little silly, but that’s also a very esoteric view. The average person’s interaction with photos for the last 100 years has been pretty one-to-one, with more recognition of manipulation as Photoshop emerged.

When you talk about the turn of the century and the advent of photography, I imagine an equation with representation on one side and truth on the other. The equal sign used to be so mysterious—whatever was going on between those two was the realm of theology and magic. But photography entered and made it more like “one equals one,” erasing a lot of that mystery.

You also talked about images being vehicles to the divine or the ineffable. A lot of my interest is in apophatic theology—the divine as that which cannot be captured or represented. “The Dao that can be told is not the eternal Dao.” I think the advent of photography is an under-recognized epistemological turning point in the way you’re pointing out.

Trevor: I really do feel that. I think it’s bigger than the invention of perspective, for sure.

Gideon: What gives me hope in this scary moment is something I was starting to get into—I don’t think iconoclasm is the answer, nor do I think icon worship is the answer. The opposite of adoration isn’t hate, it’s something like apathy or detachment. My hope is for a better relationship to images as they lose their truth claim in a popular sense—a divestment from their contents being meaningful.

Trevor: I’m imagining a presidency where you could have a Lincoln, or somebody like that who is not photogenic, not an actor…

Gideon: I’ve been thinking about when Dwight Eisenhower was up against Adlai Stevenson. Dwight was nailing the early TV commercials and campaign slogans, and Stevenson famously said, “I’m not going to appear in commercials. This isn’t dish soap.” Of course, he got crushed.

I’m not naive enough to think we’re any match for images. Our attention spans or our biology—a human brain that hasn’t changed much over thousands of years—I don’t think we’re going back to a realm where Lincoln and Douglas were having three-hour debates with people taking lunch breaks and coming back for another four hours.

But on a more day-to-day level, I hope that as images lose their truth status, we’ll have much more choice in whether we imbue or invest any emotional weight into them. There’s a part of me excited by the possibility of having that be more of a choice, and having a picture of myself really not always be “me,” or even have much relationship to me at all.

Trevor: This comes back to the question we opened with: what are all the things that images can do? What are all the things that they are? The way I understood the point of making images when I was younger was that you can effectively expand the range of what is sensible, what is intelligible, what is permitted into a cultural vocabulary—and that has political consequences.

In other words, if you say “women are people” or “trans people are people,” the creation of images is a big part of that project. And that project is not only about creating representations, but those representations have political consequences. There’s a million other ways that images work, though, and that dynamic obviously has a dark side as well.

“I worship superposition—reality before it is measured and takes form.”

Going back to the Second Commandment question: in the world you imagine, where we’re either more suspicious of images or we get rid of the idea of indexicality—if we detach images from the transcendent and that becomes a cultural norm—do you still need to have that transcendental signified somewhere in culture to have a coherent society? You can have a theocracy organized around the collective understanding of a god, or a democracy organized around a transcendental idea of empiricism. In the world you’re imagining, can you envision a world we’d want to live in that either had no transcendental signified, or where it was replaced with something that was neither this photographic, empirical a priori, nor a kind of theology?

Gideon: My formative experience with religion and spirit came from Buddhist meditation retreats. I used to go on 10-day silent retreats when I was very depressed after quitting Magnum. I remember walking into one of these retreats and hearing “The first Noble Truth is dukkha —life is suffering,” and I thought, “Now you’re talking. I’m in the right place, because this hurts.”

In some ways, you could read the Four Noble Truths as essentially: life hurts, and suffering is born out of expecting reality—ephemeral and always in motion—to possess qualities of images: stability, solidity, simplicity. Images present a false promise of what life really is on this plane.

I think images—even taking the Second Commandment in the less orthodox version—are dangerous. Especially now that they’ve gotten so immersive and dynamic, we’re no match for them. The problem is worshiping them.

I worship superposition—reality before it is measured and takes form. At this point in my life, I equate superposition with divinity: a cloud of possibilities before it manifests here.

What does a society like that look like? In my individual life, it makes me much happier. I’m not living and dying with the life and death of images. Images can change, come and go, be as scary as the apocryphal train in that Parisian theater at the turn of the century [referencing the myth of audiences fleeing in panic at the 1896 screening of the Lumière brothers’ train film]. The world of forms can do whatever, and it’s more up to me whether I’m going to jump out of the way of that train or not. I have slightly more agency.

Trevor: I think that’s a good place to land.