Design meets desire in Vezzoli’s Monte Carlo show, a vivid reconstruction of Lagerfeld’s 1980s fantasy apartment—and a reflection on queer interior worlds

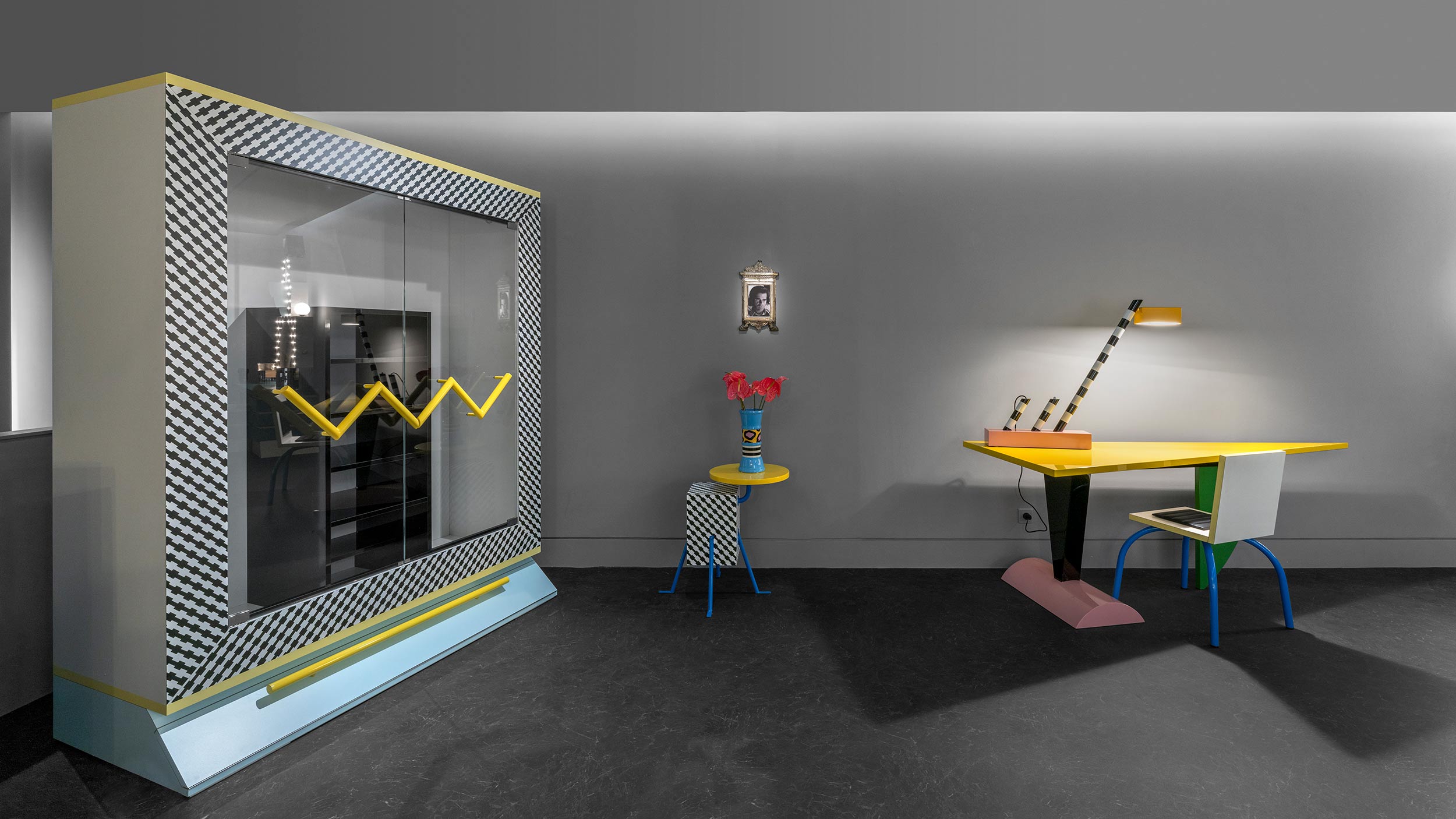

When Karl Lagerfeld, fashion’s most notorious monochrome minimalist, filled his Monte Carlo apartment with the riotous, color-saturated furniture of the Memphis Group in 1983, he created an unlikely temple—one now resurrected by Italian artist Francesco Vezzoli in his latest exhibition. Running at Almine Rech in Monte Carlo through May 24th, Francesco Vezzoli presents: KARL GOES TO MEMPHIS Tribute to a historic encounter in Monte Carlo is a meticulous reconstruction of Lagerfeld’s space, complete with dozens of original Memphis pieces alongside Vezzoli’s new works: eight portraits of Lagerfeld in baroque frames.

This isn’t Vezzoli’s first attempt at full-scale reconstruction of a sacred site. In 2013, he purchased the ruins of a 19th-century church from a southern Italian town, intending to reassemble it brick by brick in the courtyard of MoMA PS1—until Italian authorities intervened and clipped the project at its foundation.

Over the course of his three-decade-long career, Vezzoli has been featured at the Venice Biennale four times and has cast a glittering A-list of Hollywood stars in his film projects. Given his pedigree, you might expect some pretension in conversation, a bit of self-indulgent artspeak. And yet, during our phone interview, Vezzoli is remarkably down-to-earth, his approachability polished by a suave charisma and wit. Throughout our correspondence, on WhatsApp chats and group email threads alike, he would freely punctuate his messages with psychedelic hearts, glinting diamonds, and spinning pink roses from his arsenal of digital stickers. His playfulness with virtual iconography spills into the exhibit itself. Some artworks feature emoji waterdrops trickling down Karl Lagerfeld’s face; others depict him weeping Vezzoli’s signature embroidered tears. “Emoji is a fantastic vocabulary,” he explained, noting the waterdrops’ double entendre. “In gay/queer/Grindr vocabulary, they have a completely different meaning, so I love painting them on the face and on the swimsuit of Karl Lagerfeld.”

Despite his small-town provenance, the Italian pop artist was among the first of his generation to speak openly and casually about his sexuality. His own apartment, extensively documented online, is an exquisite sublimation of a quintessential gay neurosis—the obsessive drive to live in a gorgeous, immaculately furnished apartment. His curated collection includes rare Yantra vases by Sottsass, iconic Memphis furniture pieces, and a life-sized bronze of Sophia Loren modeled after de Chirico’s robed muses. His domestic universe might itself be reproduced in an exhibition someday.

Vezzoli sat down with Document to discuss the yet-again resurgent fascination with Memphis, its resonance in our anxious global reality (as expressed by his visceral reaction to this week’s all-woman-crew space flight spectacle), and the sophisticated loneliness mastered by gay men of a certain age.

Adnan Qiblawi: Ciao Francesco

Francesco Vezzoli: So nice to meet you Adnan. Did I pronounce your name correctly?

Adnan: You did, perfectly.

Francesco: Where are you from?

Adnan: I’m from Beirut, Lebanon. I’ve been in New York for 12 years now.

Francesco: And how long have you been working for Vogelson [Editor in Chief of Document Journal]?

Adnan: Not very long. How long have you known him?

Francesco: Long enough. Actually, I love him. I think he’s doing a great job. It’s a very weird moment for America, and I think he’s delivering a product that has all my respect.

Adnan: I feel like it’s not just a weird moment for America, it’s a weird moment for the whole world, really.

Francesco: Yeah, and America is helping to make us feel even weirder.

Adnan: I recently read the idea that the resurging fascination with Memphis is connected to our anxious global reality. Do you think there’s something to this?

Francesco: Well, certainly, when Memphis showed up, it was the peak beginning of the end for the Italian Red Brigades (or you can call it the civil war), a moment when political tension in Italy competed easily with what the United States is going through right now. In Italy, the years of the civil war were called the “lead years”—”Anni di Piombo”—to define the heaviness, the gloom of that period. And so Memphis, when it showed up, with all that color and with all that craziness and with all those unexpected shapes, and some wild references to plasticity, and a weird sense of eroticism—Miami, Los Angeles—it brought to the table a whole range of senses that had been erased during the dark years. So maybe people will soon want more Memphis in their life. At some point, regardless of what is wise or what is not wise, the human being is naturally inclined to look for some oxygen.

I mean, and forgive me for saying this, but those six women going into space yesterday, I was horrified. Horrified.

Adnan: [laughs] Tell me why.

Francesco: Because that is the most perverse, oblique, manipulative way of making politics. You’re a businessman who has made clear his proximity to the evil power that is running the country, and you put together a bunch of women that deliberately are trying to represent orientation and nationality and provenance. I find that horrifying. That’s manipulation of the public opinion. I wonder how someone like Oprah has accepted to send their pseudo-girlfriend into pace with that wife of Jeff Bezos. No—just a bunch of scary people for me. I’m not gonna listen to a Katy Perry song for the rest of my life.

Adnan: It is a horror. Do you feel that Italy is feeling the global anxiety that we’re talking about that might be leading to this reinterest in Memphis?

Francesco: The political climate here is slightly different from America, but certainly yes. To speak seriously about this, radical design is a very important chapter of our history of architecture. Radical design was on the forefront back then, and I think it’s still on the forefront now. Because when it comes to interior decoration, people have been quite reactionary in the last decades. So what I love about Memphis is that it has not lost its crazy power. Do you agree?

Adnan: I certainly do. Memphis design has gone in and out of fashion maybe five or six times since its ’80s debut. There’s a reason people keep coming back to it.

Francesco: If something has a crazy power from an artistic perspective, then it’s a good thing. It has some sort of intellectual value, from my point of view.

Adnan: And what drew you to make this show now?

Francesco: The answer is actually very banal. It was actually a geographical thing. I’m not an artist that is about his studio, or so much about producing the perfect painting and then sending artifacts around the world. That’s not the way it functions for me. Every project is a kind of made-to-measure idea. For a long time, Almine Rech was offering to let me do something in Monte Carlo because she was about to open the gallery there. I was always thinking about what would work well, because Monte Carlo is such a characterized place. It’s like a little land of fairy tales, but at the same time, it’s where the ultra-rich go, not always for the most noble reasons—to avoid paying taxes, etc. Monte Carlo has this multifaceted mythology.

At some point I realized, “You know that the apartment of Karl Lagerfeld was done entirely by Memphis?” That’s the thing that should be back on the map. What was really exciting is that there isn’t actually an academic book about it, which is what I hope our book will achieve. What happened there—such a strong statement from such a powerful pop figure who decided to live completely immersed in the fantasy of a rather anarchic and radical architecture avant-garde—it rarely happens, and it needed documentation. So I was lucky that the Memphis people wanted to cooperate with me, that they gave me all the blueprints and reconstructed some pieces that were made to measure to fit Karl’s apartment. It was super exciting.

“At some point, regardless of what is wise or what is not wise, the human being is naturally inclined to look for some oxygen.”

Adnan: So this is more a documentation than it is an ode or a love letter to Memphis or to Karl, or is this both?

Francesco: It’s both, especially because I was very close to Ettore Sottsass, who was the founder of Memphis. I’ve made my declaration of love to him already many times. I collect his work when I can, and I’m a big fan of his. I knew him really, really well.

Adnan: What was your relationship with him like?

Francesco: Well, Milano was a different city. If you were like me, a kid from the province arriving in the city, the only stars Milano had back then were the designers, and the fashion designers (but I was not working or interested yet in fashion). But the real stars and the real industry for which we were on the top of our game was the design industry. So Ettore Sottsass, Achille Castiglioni, they were really the best in the world at their job. They were the stars. When I met Ettore, he was always very friendly to me. He had spent many years in America, so he was very cosmopolitan, inclusive, open-minded. You just wanted to listen to him, to his perspective on culture. He was a great photographer, a great writer. For me, he was one of the most inspiring people I’ve ever met.

Adnan: There is an element to this show that speaks on the gay sensibility. Can you tell me about that?

Francesco: Yes, I realized this only a few weeks ago. There are very few examples of this kind of immersive house in the history of design or architecture. The ones that come to mind are the Paul Rudolph Halston/Tom Ford townhouse, and then there was a moment before the Second World War when a famous count commissioned Le Corbusier for an apartment overlooking a fantastic panorama of Paris.

I believe that these kinds of hyper-immersive architectural experiences, in these three cases at least, were commissioned by single gay men. Given the different time frames, they hadn’t done an official coming out, but their sexual identity is now widely taken for granted. Such radical experiences of living immersed in someone else’s architectural brain was a way of projecting a fictitious identity. There was something practical—the gay men of the ’30s, ’60s, and ’80s inevitably didn’t have a family, didn’t have children. Those are only acquired rights of the last decade. But back then, it was about a certain kind of sophisticated loneliness. This kind of projection, this kind of courage was a compensation for the loneliness.

I think it’s the essence of queerness in some ways—something has been taken away from me, so I’m going to be more daring, more courageous. I’m going to take a very daring perspective on life and aesthetics. That’s a mechanism that has ruled upon aesthetics in the 20th century. Now it’s completely different, but even if you’re young, I’m sure you get what I’m saying.

Adnan: I understand completely. When I read about your exhibition, it made me think of growing up gay in Beirut. I thought of my older ex-boyfriend, and how his home was an articulation of his beauty and his sadness. It was at once an expression of his gayness but also his baby, his child, his project that he channeled all his existential dread into.

Francesco: You see? You shifted this perspective into your country that for so many reasons—religious, political—had a completely different unfolding of gender identity and sexual problematics, and you immediately spoke about the gay person in the late 90s with the perfect apartment, with the obsessive collection. You gave me the most brilliant answer, not only because it comes from a person that has both an experience of America and an experience of a place in the world that is very different from America. You basically counter-proved exactly what I was trying to say.

Adnan: So is that what Karl is crying about in your artwork? With your embroidered signature tears streaming down his face.

Francesco: Yes. There’s always a mirror in the game, it’s always Karl mirroring himself. It’s about perception of the self—how you perceive yourself, how others perceive you, and whether that has to do with your sexual identity or your age, the two big taboos.

It’s funny because I’m supposed to be the first post-war Italian artist that has dealt in a very open way with his sexual identity. It seems crazy, but it’s written. I had my artistic coming out in my first interview with what was then the most important magazine for art in Italy, Flash Art. I had just finished my first project. Literally 30 years ago, they gave me my first cover.

After having studied in London and meeting Leigh Bowery and whatever, I was speaking in such a loose way about my identity. I had left Italy behind. I just took that the world was open-minded as a rule. At some point in the interview, Massimiliano Gioni, who now is the director of the New Museum in New York, asked, “So what is your work all about?” And I replied, “It’s about the obsession of a provincial faggot who wants to live in a house full of perfect furniture,” or something like that. And they printed this sentence so big. I couldn’t really understand, but it was like I was coming out without planning it.

But it just goes so perfectly back to what you were saying earlier, and to the tears, and to the reflections, and those pictures of Karl at the table projecting the perfect identity of the designer. I think this exhibition was a due gesture, and I’m happy I’ve done it. The most stupid thing an artist could say is “I’m happy I’ve done it,” but it’s true—I’m happy I’ve done it.