Fashion designer Elena Velez thrives in paradox, daring the fashion world to digest contradicting narratives and the rawness of self-exposure in her latest collection, ‘Leech’

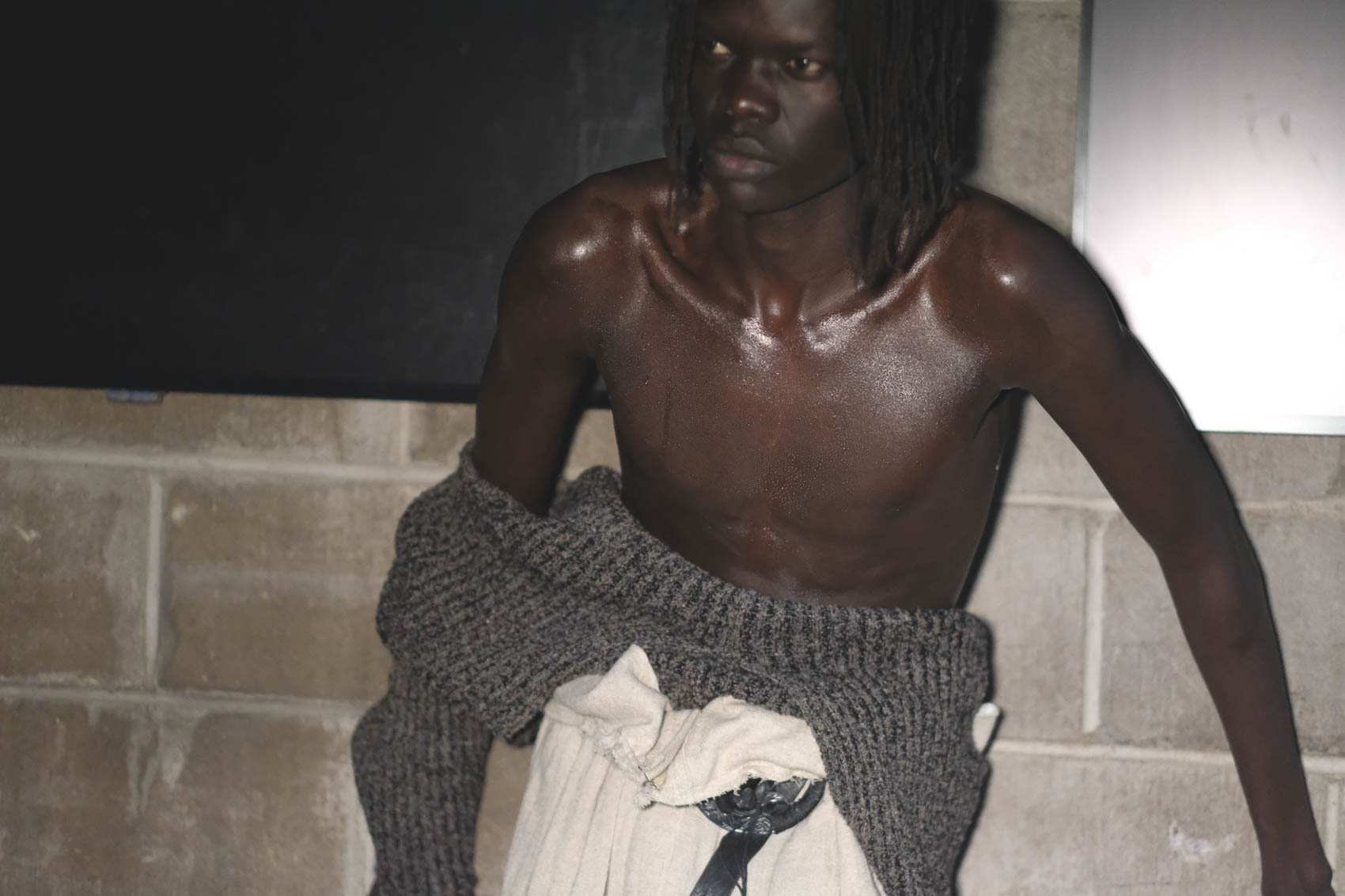

“I’ve created an autobiographical label, exploring a composite of feminine archetypes. This season feels like a biopsy—of myself as a founder, muse, and brand,” says Velez of her Fall/Winter 2025 collection, Leech. Backstage at the show, models practice: walking in elongated bustiers jingling with mismatched keys, sneering in mirrors, undulating their shoulders which are cast in an oil sheen from a mysterious mist. Leah McSweeney, between getting spidery false lashes applied, says that movement direction is involved, and that each model is a different character of the sea. And when lights are up in the showspace, the all-white room transforms into a runway-shore replete with large sandy rocks dotted jutting from the floor and a projection of a dim gray ocean on the walls, the smooth pull-push of the wave-y soundtrack deepens into a trance-like pulse, a siren’s song. Anna Delvey (ankle monitor and all) in a faded green leather skirt suit opens the show, staring hauntedly yet self-assuredly to the audience. Rico Nasty closes, slinking slowly between the rocks in a stained leather corset, a matching tall crown atop her head like a piece of black coral. “I’m fascinated by the siren and the snake—sailors and sirens, Eve and the serpent—mythological figures that blur good and evil,” says Velez of her collection. Models in wet-looking tattered dresses that resemble seaweed and boned wet t-shirts enchant audience members, some the temptresses, with slicked back hair and frocks layered with twine fencing like fishing nets, and some the tempted, dressed like wayward sailors who got too close, with half-buttoned paper bag pants and high-neck cotton shirts. “At a time when grand narratives feel obsolete, I want to explore new, imperfect depictions of female power.”

I met Elena Velez outside of Sovereign House by accident. (I was invited to the launch party for Frontier, Glenn Beck’s magazine platforming conservatism as a lifestyle on what I can only assume was a fluke due to saying “Trump” a certain number of times in this essay). After being loosely profiled by the conservative haunt’s owner, enter Velez, who was stepping out for a smoke. I got the sense that Sovereign House Owner (forgot his name) introduced us as a joke, not thinking we’d get along.

But, we did. Velez—tall, with long dark hair and bangs resembling Emily the Strange, wearing a dark red lip and a camel-colored wool coat—was easily the chicest person at the event. I knew very little about her as a person: she’s a fashion designer, she’s married to an artist, she has two children, she pals around with the women of Red Scare. She greeted me warmly, asking what brought me to Sovereign House, and I told her, in as many words—perspective. It wasn’t the time for a full proto-interview on her design practice, one which I’d admired since my Drunken Canal days in 2020, so I ask her a question I’d had on my mind since February of 2024—what, in her own words, was the thesis behind the Gone With the Wind-inspired collection, oft-criticized for its racist overtones? And between sips of her cigarette, Velez lit aglow. She told me how the collection was meant to center the toxicity of girlbosshood, proffering 19th-century slave-owning white women as, perhaps, the first girlbosses who, in their apathy, were complicit in unspeakable violence for the sake of their own advancement. And in many ways, this is a concept that white women, in fact most people in general, are not able to see in Velez’s Fall/Winter 2024 collection, let alone hear—that there is a conceptual parallel between the Sophia Amoruso-type girlbosses we know contemporarily and the Scarlett O’Haras of yore, with plantation-owning lineage. And there on that rain-slicked street, I recognized the merit behind Velez’s willingness to provoke, even in the face of public scorn. It was the whole conceptual point of her design practice.

“In all of her iterations, the Elena Velez woman is morally reprehensible, full of rage, and gorgeous not in spite of her tendency toward violence, but because of it.”

“Fashion design felt like an unusual obsession, especially before I even had the language for it,” Velez tells me in a conversation over Zoom. The designer is of both Hispanic and American heritage, born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin as an only child to her single mother, a ship captain on the Great Lakes. “When Project Runway came out, I finally saw a path. My mom, though she didn’t fully understand my passion, supported me by finding sewing opportunities—Joann Fabrics after school, church friends with sewing machines.” From age eight, Velez knew that she wanted to attend Parsons School of Design at The New School, a goal she later accomplished, as well as earning her masters of fine arts from Central Saint Martins’ Fashion Design program. Through her studies in New York City and London, however, the designer maintained both a fascination with and appreciation of America as a country full of beauty and contradiction. “My senior thesis [at Parsons] explored World War II’s controlled commodity industry, balancing visual destruction of wartorn landscape with craftsmanship techniques that celebrated human-centered ingenuity and resilience,” she says. “I’m drawn to paradoxes; juxtapositions that feel modern, and tell layered narratives.”

So, what do we see when we look at an Elena Velez collection? In the case of How’s My Driving? from Fall/Winter 2023, it’s a series of sportswear-inspired shirt dresses and stained-looking corset-pencil skirt combinations brought together by a sense of urgency, even homicidal ideation, on the runway. (One model carried Velez’s CFDA award “like a bludgeon,” reported Vogue Runway’s Laird Borrelli-Persson in the show coverage.) For Spring/Summer 2024’s The Longhouse, models mudwrestle in eveningwear stained with silicone latex, shredded knit shifts, and waxy-looking draped bomber jackets. OnlyFans was a sponsor for Spring/Summer 2025’s La Pucelle, and Plan B was offered for free at the show’s afterparty. The clothing possesses the je ne sais quois of a good designer, in that it fits impeccably (and looks stunning on multiple different bodytypes), and is able to tell a story through these elements, from birth control and mud to exquisitely constructed full bustle skirts. In all of her iterations, the Elena Velez woman is morally reprehensible, full of rage, and gorgeous not in spite of her tendency toward violence, but because of it.

Velez is able to tap into less-than-traditional ideas of womanhood because of her upbringing, which inspired an intrepidness the designer attributes as distinctly American. She started her company in 2018 after deep self-analysis made her realize that she was using school “as a safe space to avoid having to jump into the industry,” she says. Between her formal start in 2018 and her relocation to New York City from London in 2020, a move spurred by COVID lockdowns she experienced after receiving her Graduate degree, the designer had been recognized by i-D Magazine and Teen Vogue as one to watch. By 2021, Velez’s brand was written up in Forbes, for centering production in the Midwest, a rarity in the industry that the designer says honors her roots, and in 2022 she won the CFDA Award for American Emerging Designer of the Year. In the face of her mounting success, (she’s dressed artists from FKA Twigs to Taylor Swift, and was a semi-finalist for the 2024 LVMH Prize) she remained true to her design perspective, an intentional image of woman as villain.

“I’m interested in women fully integrating their shadow selves—embracing their complexities while remaining resolute. That kind of depiction is missing in 2025,” says Velez. And this idea broaches one of the most interesting aspects of Velez’s work, her boundless pursuit of capturing multitudes by way of clothing on runways. In many ways, the critique posed against her Fall/Winter 2024 collection can be summarized as a misreading of the designer’s intentions, which were not effectively communicated to audiences in a way they could understand. If you see clothing inspired by plantation women, it only makes common sense to live in that moment of shock when that shock is meant to create a barrier for entry into her world.

Though, Velez’s sense is not common, on purpose. There is a level to her work that seeks to alienate people in this way, to shock them into either diving into her lore, or shunning her as a hapless purveyor of rage-bait. An Elena Velez collection feels almost like a test, asking audiences to choose to love her or hate her. To love her is to participate in her carefully constructed balancing act, her demonstrable talent on one side, the fact that she maintains at least social alignment with downtown’s mouthy young right adjacent on the other. To hate her is to stop at the shock she goads. Velez was spotted having a ball at the New York Young Republicans Gala in December of last year with the ladies of Red Scare, a rather opaque expression of her own politics. Or, is it? This is the question Elena Velez wants audiences to grapple with—how much truth is in an assumption, what kinds of evidence are required to socially indict?

Velez’s social life, when interpreted as a breadcrumb trail to her political beliefs, might lead to an answer. But to know the designer and her work is to know that she’s an unreliable narrator. Her trail will always mislead you because it’s designed to be unfollowable. While Fall/Winter 2024 may look like a misstep, what with its aesthetic symbols of plantation America and a later salon where Anna Khachiyan of Red Scare made an “I can’t breathe” joke, Velez and her point of view are not misguided; perhaps the execution this particular season can be read as such, but the attempt is sound. For Velez, the balance of contradiction, truth, and belief is material for her collections. “My work is a smoke signal for those craving depth in fashion—people tired of being patronized by the creative industries’ platitudes and condescensions. I want to prove you can operate on your own artistic difficulty setting and still succeed,” says the designer.

“That event was dense and ambitious—I’m still unpacking it,” she continues. “I’m drawn to American anti-heroines and flawed female figures, and in 2020, downtown New York was obsessed with Gone With the Wind. That cultural moment mixed with my own experience as a ‘contentious female founder,’ plus the hyper-censorial feeling of the city then, made the collection feel urgent.” To disavow or to laude her work is perhaps the least interesting bit about both Elena Velez the person, and Elena Velez the brand. Misunderstood as much as she is marvelled at, the designer seeks perspective in a landscape that she feels is resistant to accommodating disparate ideas. Fashion is not just something she’s good at, it’s a tool for her to unify things that might otherwise not go together. “I’m biracial, bilingual, caught between high fashion and Rust Belt blue-collar America. My mother is a Great Lakes ship captain—my understanding of womanhood has always been paradoxical,” says Velez. “I’ve always celebrated blue-collar craftsmanship, non-traditional fashion perspectives, and democratizing the industry to accommodate other relevant creative identities. That was once applauded; now, it’s vilified. Nothing about my work has shifted—only the cultural center has moved.” And regardless, Velez is okay with being the villain—it’s the conceptual framework that links her with the women she fashions on runways and red carpets.

Leech is the autobiographical biopsy Velez labels it, both an excavation and a defense mechanism, a manifestation of the designer’s willingness to stage her own crucible while daring audiences to misunderstand her. In the same way Velez fashions her runways—half stage, half battlefield—she attempts to fashion herself, an image of the designer as both martyr and menace. The spectacle of her work is not just in the clothing, but in the tension it cultivates, the friction between aesthetic provocation and conceptual risk. With each season, she sharpens her contradictions into something unignorable, which is what fashion is about—impact through clothing. The question is not whether Elena Velez is good or bad, right or wrong, it is whether audiences want to participate in her balancing act, to see two things as being true at the same time, to engage with a designer who, while at times feels contradictory in her demands for non-partisan affiliation while presenting rather opaquely conservative social and political views, is an earnest provocateur with major skill. Perhaps what ideologically appears as opaque is more oblique, slanting in an unknown direction. “I care more about asking compelling questions than providing easy answers. Ambiguity makes people uncomfortable, and they often interpret it in bad faith,” says Velez.

“I thrive in America because the American Dream is real—I’m living it. My work isn’t sentimental or nostalgic; it’s about defining what it means to be living in America, now. I use historical references to amplify the present, not to look back.”