The artist’s work at the Sphere distorts time, identity, and the limits of perception—he sits down with Document to discuss both the human and post-human influences in his multimedia craft

Alexander Wessely’s most recent work, Afterlife presents Anyma: The End of Genesys is set to return to the Las Vegas Sphere at the end of the month following a sold-out run. The live performance collaboration with the multidisciplinary DJ, Anyma (Matteo Milleri), is as much an evolution of Wessely’s practice as it is a return to his roots. Similar to Wessely’s work, which incorporates photography, video, sculpture, and live experience—often all at the same time—Wessely’s path has been fluid. After cutting his teeth in photography, he began to feel “limited by the camera as a tool.” This pushed him towards more kinetic forms; video, music, and eventually, performance installation. Today, Wessely collaborates with artists such as The Weeknd, 070 Shake, and Grimes, and his work has been displayed in spaces across the world, from museums such as Fotografiska, to venues including the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Sweden and Madison Square Garden.

As the live arts space continues to adopt new forms of technology, there remains a human touch to Wessely’s work, which he carries into each project. This can be traced to his background in sculpture, a craft which he took up over a formative few months assisting a family of sculptors in Greece, where he spent part of his youth. With several projects in the works, Wessely maintains an experimental spirit in his practice, much like the various channels he worked in that led him to his multimedia approach in the first place. It’s a curiosity based on pushing boundaries, between real and surreal; human and posthuman. Across all of Wessely’s work, from his marble busts—previously on display at Fotografiska in Stockholm as part of his 2023 solo exhibition, Kortex—to the haunting, larger-than-life holograms that came to life at the Las Vegas Sphere this Winter, he maintains a corporeal concern with the human form at its rawest level.

Ahead of his performance series with Anyma at the Las Vegas Sphere, Document sat down with Wessely to speak about the origins of the pair’s collaboration and his ever-evolving practice.

“In the first 10 years of my career, I was trying to figure out what medium I wanted to work within, and now, for the last five years, it’s been more choosing the medium after the idea.”

Nick Vogelson: To start off, I wanted to take a few steps back. Can you share the story of how the collaboration between you and Anyma first began?

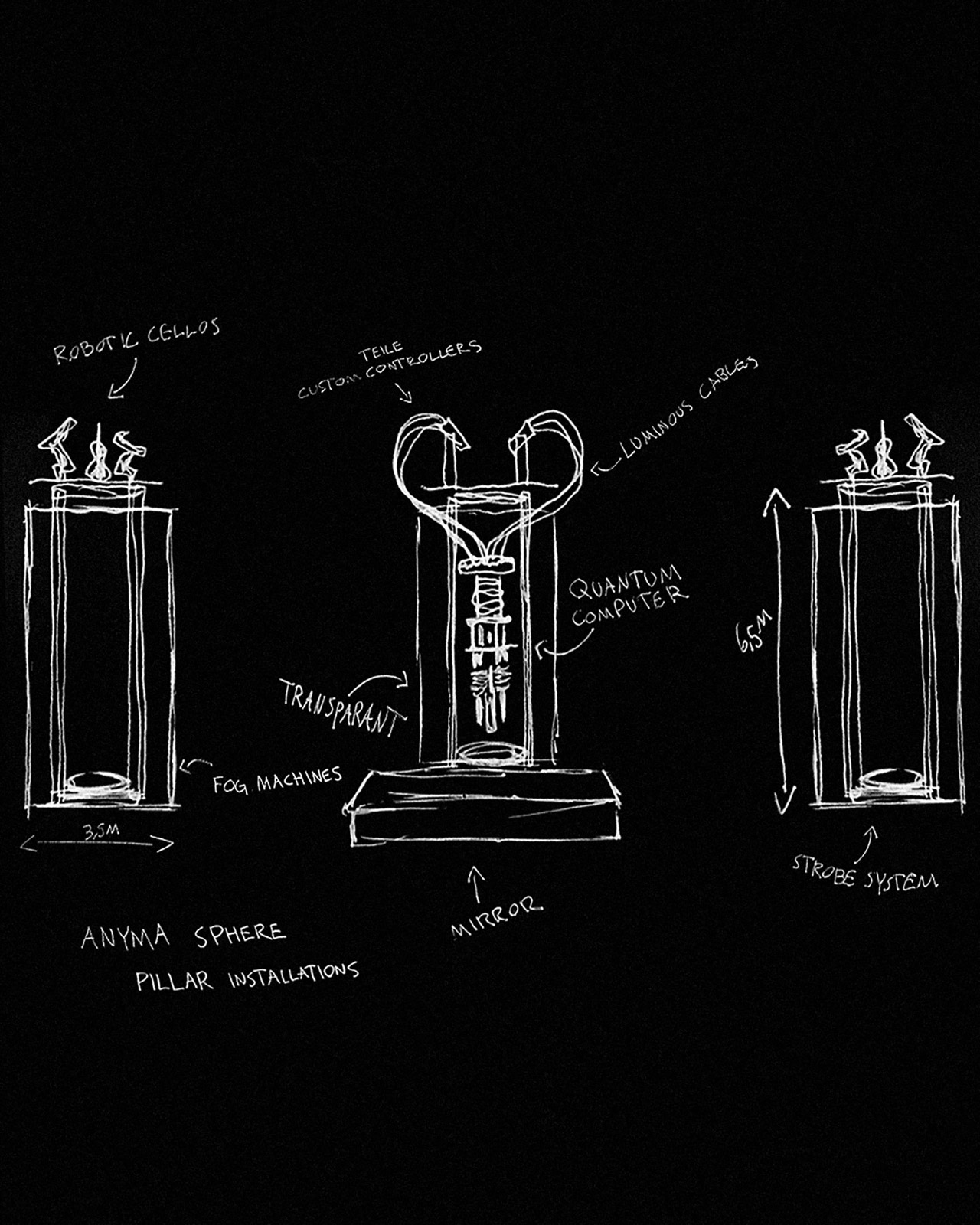

Alexander Wessely: It started out in late March when Anyma’s manager and long time friend of mine, Evan Baker, reached out and said ‘I think you guys should meet, I think there are a lot of synergies going on here, and Anyma has some quite interesting plans ahead.’ So in early April, Matteo (Anyma) and I met. He’s very straight to the point, so after 45 minutes of discussing everything from family to what inspires us, he asked me to be his creative director. He told me he was doing the Las Vegas Sphere later this year, and wanted to do a cybernetic opera. That directly drew my mind to a project I’ve been working on with the Swedish composer Jacob Mühlrad creating robotic cellos, so I threw that out there in the very first meeting with Matteo, and he loved the idea of it. Two weeks later, we were up and running.

Nick: It seems that a lot of the work that you do is very prescient, and very intuitive for you. Could you tell me a little bit more about the genesis of your practice? Specifically, how did you start to combine the understanding of light and image-making from your photography background with experience and how and how that’s gotten you to where you are now?

Alexander: The first 10 years of my career, between the ages of 20 and 30, were years of being almost confused, very curious, and very experimental. I was always trying to find the correct tool to express my ideas. I went to photography school in Sweden, and started out as a photographer for the first few years of my professional life. When I started to feel limited by photography, or by the camera as a tool, I abruptly stopped and started looking for new ways to express myself. I’m half-Greek and grew up part-time in Athens, a place which has been a main source of inspiration for me. My grandmother always preached Greek philosophy, history and everything in between. In 2016, I spent three months traveling around the country exploring sculpture, which is when I came across a family of fourth-generation sculptors outside a holy city called Meteora in central Greece. They took me in with open arms, and I started assisting in their studio.

Parallel with this, back in Sweden, I started exploring film and working with musicians, doing a couple of music videos here and there with various artists. It was quite messy, because all this time I was hesitant, and always asking myself, ‘What am I really doing?’ I was exploring all of these different things, but just dipping my toes because it never felt 100 percent. In 2019, Swedish House Mafia reached out to see what it would look like if I did a full artist project with live stage design, lights, visuals and full creative control. From there I started working with The Weeknd, we did the main stage of Coachella together in 2022, and more recently, a live project in São Paulo for his latest tour. In the first 10 years of my career, I was trying to figure out what medium I wanted to work within, and now, for the last five years, it’s been more choosing the medium after the idea.

Nick: Can you talk a little bit more about your interest in sculpture, and your time living with the family of sculptors in Greece?

Alexander: It’s nostalgic, for one—some of my earliest memories are of living in Greece around my Yiayia and Papou (grandmother and grandfather), and the contrast between Greek architecture, Greek art and the history surrounding the two. On the other leg of it, memories are like scaffolding, these core sheets that encapsulate us. So it’s this very raw, brutalist thing that came along to preserve these works and has ingrained itself into the way I approach stage design. Sculpture, for me, is to create something ethereal and timeless that looks in on human expression. And then there’s the question of how to do it in a way that’s interesting in these times, which is where technology comes in. At this point, 50 percent of my process is machines, or carving out of the base block of stone, and the other half is retouch, which is that human element to it. The sculpture side of my practice is rooted far down into my being, in my childhood, and now venturing into this more pop-culture driven commercial world, these interests have really flourished. Now when I visit Athens, I do the same thing as I did when I was 20—go to the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion on the very Southwest point of the mainland. There’s a huge juxtaposition between sitting there versus being in the Sphere, but there are also a lot of synergies.

Nick: I wanted to ask about how you think about the boundaries of your practice, and what the limitations are, if there are any.

Alexander: Limitations have been out the window since a couple of years back. If there were any limitations within the actual craft or practice, or the mediums, there are none anymore.

Nick: Can you speak about what shifted in that moment a couple of years back?

Alexander: I came to this point after almost 10 years of trying to find myself and trying to fight what was coming to me, trying to find a perfect situation where I felt like it was all aligning and I had found my calling. All of a sudden, I was reviewing the past 10 years, running through photography as a medium, film as a medium, stage design and performative works, and I came to a point where people began reaching out wanting a mix of all these different things. That’s when I switched mentalities and asked myself, what happens if I don’t fight what’s coming to me?

This is a weird translation, but in Swedish, we say ‘with a straight back,’ meaning you’re not compromising. So as long as it’s not a compromise of my integrity or vision, I can figure out the medium after the idea. I’ve been running with this for the last five years, and it’s brought an insane sense of freedom to be limitless in what I do. When I started exploring sculpture 8 or so years ago and was meeting with galleries and agents, they’d tell me I needed to choose my path, to focus on one thing. I think now we’re living in very interesting times creatively, in this space where disciplines are merging, and everything is becoming this blob of expression. Looking back, it makes me very happy to feel like we are in quite fantastic times for expressionists that want to do things but don’t want to be boxed in in any way.

Nick: Now, going back to the performance at the Sphere, there’s clearly a lot of different collaborative processes, and I was curious if you could speak to the process of actually producing the work, and the tools you used to make it.

Alexander: When joining the project, we spoke with the art director and the lead visual artist, Alessio De Vecchi. He and Anyma already had a long standing collaboration where they established the base aesthetic of Anyma, which is a robot. When I was invited into the project as Creative Director, it felt very natural and organic to invite this sense of humanity, emotion and skin to the project. The very first piece we did together was one with Grimes, where she’s basically nude, but in this genderless humanoid shape—we really wanted to feel her inside the glass, wanting to get out. With everything being heavy VFX and CG, I was lucky to be working with an amazing team of people. It hasn’t been too far out of the ordinary. We have still been working in a studio. We have still shot on a regular camera. We have all these technical boundaries in mind, but it hasn’t felt damaging creatively and it’s also been quite a journey on a learning level to understand how complex it is to make something work in a projection space.

Nick: Lastly, I wanted to look ahead at what projects you have coming up that you might be able to speak to, and what are you most excited about?

Alexander: My taste for these immersive works has definitely grown after this most recent project, and so has what was one of the driving forces, the narrative that of blurring the lines between reality and imagination, forcing the viewer to question what’s what’s real and what’s not. It’s almost like a dream space where the audience forgets about reality for a period of time. These types of projects are more intriguing to me than ever.