In ‘LIBRARY,’ four live acts revel in the absurd, magic, and tender possibilities of literary encounters

The library has always been a site of worldbuilding. Its meticulous taxonomy of genres and subgenres opens new paths to information and new grounds to contest what is and isn’t included. It becomes a space for memory—and perhaps even a space for living. Jorge Luis Borges takes up this metaphysical dimension in his 1941 short story “The Library of Babel,” which conceives of the universe as an ever-shifting library. Communities and even civilizations form in all corners of this library. They organize religions and cults to deal with the impossibility of accessing truth in this seemingly infinite library that’s expanded beyond usability. Violence and disease arise. The library’s residents feverishly and methodically search for, guard access to, and interpret mysterious books that are said to reveal the truth of this life and what is to come.

The same concerns that establish the library as a heterotopia in Borges’s story— the peripheral as the center of knowledge production, crisis as the new normal, and the flow of time as as a series of arrested developments—become the parameters of LIBRARY, a multi-part, one-night-only performance program curated by writer and editor Whitney Mallett at Performance Space New York in the East Village. The evening celebrated the launch of the fourth issue of Mallett’s The Whitney Review of New Writing, a print-only publication in which writers and artists adopt stylized and personal approaches toward literary reviews. LIBRARY took the performative dimension of language further by presenting a video and four performances that highlighted the eruptions of passion that challenge the seeming systematicity of language.

The first acts of the night were by Kellian Delice, who presented two scenarios that drew attention to the spatially embodied aspects of political speech. In a neon-lit room adjacent to the theater, audience members waited to be invited to their seats while enjoying the offerings of the open bar. On a television screen installed mid-air, the documentation of Delice’s February performance STAR SPANGLED BANGER at movement space Pageant played on a television screen. In the video, the lines between performer and spectator are murky: a naked Delice, with his vision obstructed by a black plexiglass box, sings the national anthem and photographs the mostly white attendees. He poses in a dress made of physical issues of The New York Times. STAR SPANGLED BANGER draws attention to racialized differences and how the public circulation of language constructs and distributes these differences. Delice refuses to participate in this game (or field of play) and instead chooses to blow up these invested sites of power from within.

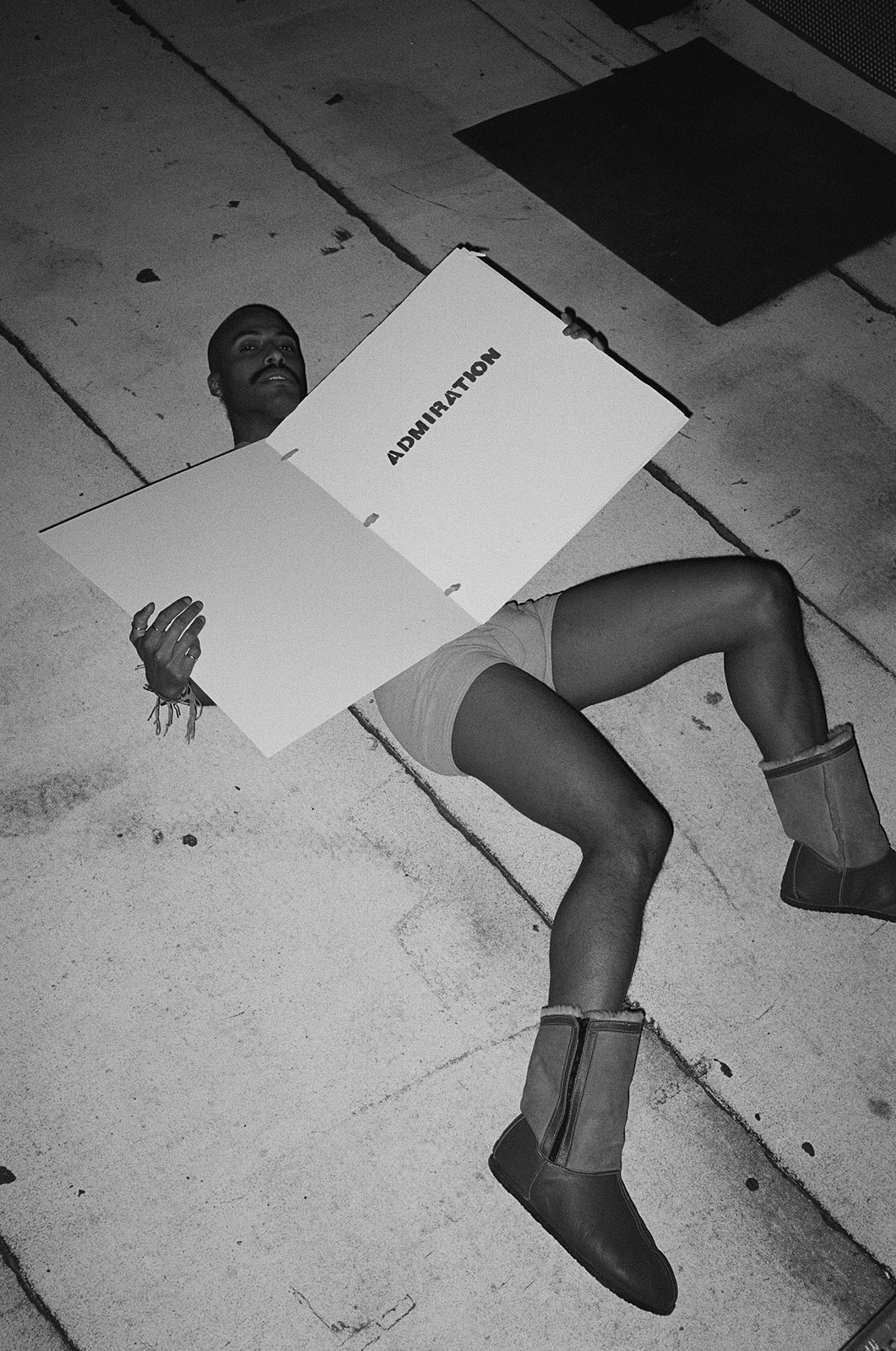

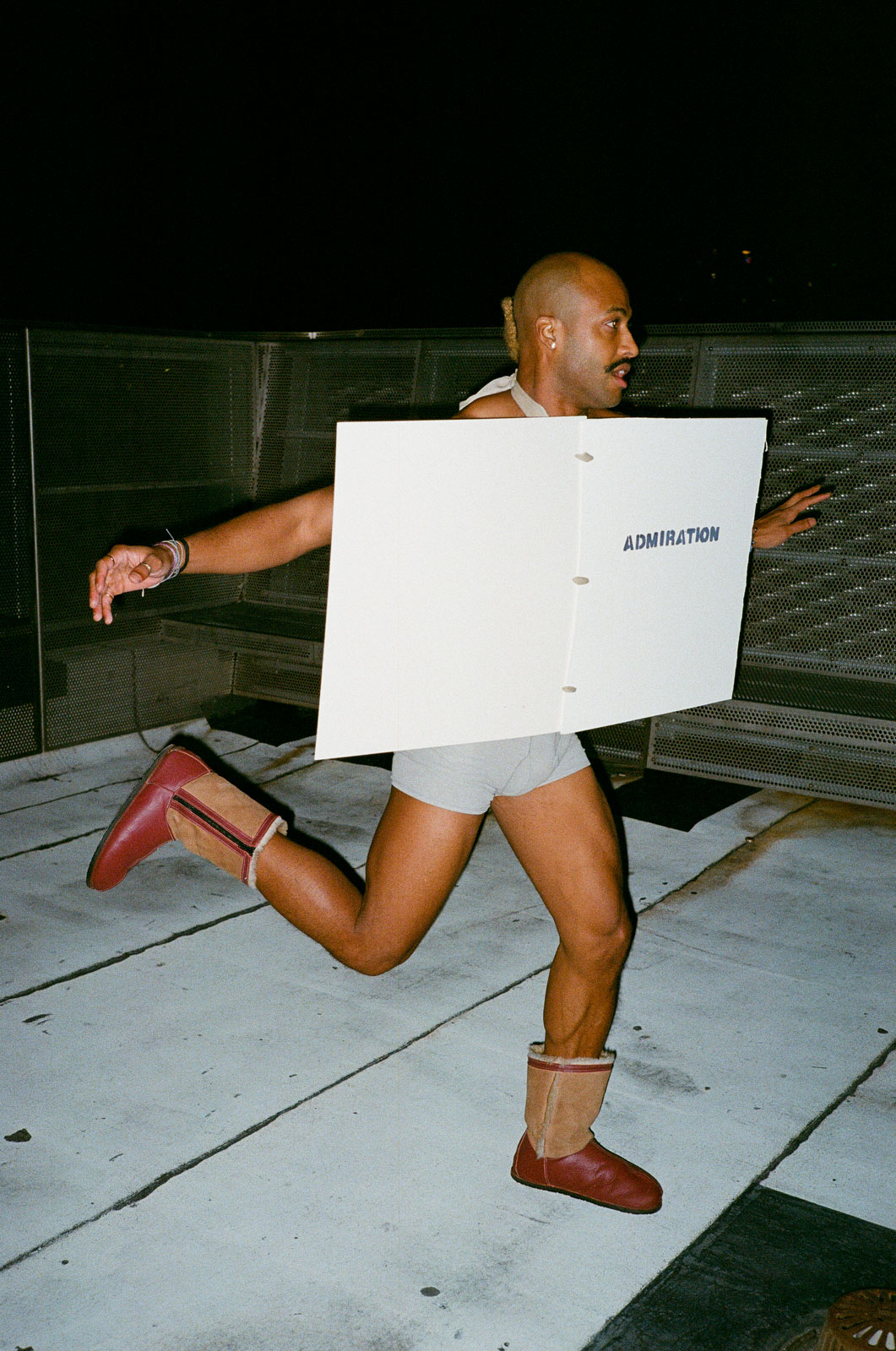

For his live performance in LIBRARY—I’m an Open Book—Delice dug further into what he described as an investigation into “celebrity culture, Black identity, white power, and moral disconnection.” Guests were invited one at a time to pass through hanging plastic sheets at one end of the hallway into Performance Space’s main theater. As they moved through the hall, performers on either side who wore only underwear and cardboard boards like oversized books shouted out pairs of morally or politically loaded words like “change” and “integration,” “status” and “greed” and “progress” and “loss.”

I’m an Open Book mines the generative force of language in describing and prescribing reality. By reappropriating words that ethically implicate us, I’m an Open Book gestures toward library as a contentious site of public formation—its function has become even more urgent given current far-right assaults on library systems—where collected objects of knowledge and history constantly are recontextualized within and outside, leading to newly invented or revived ideas of what community is.

Inside the theater, a desk was placed in the middle of the stage. Behind the desk stood filing cabinets stacked atop each other, flanked on either side by step ladders. The first performance in this space presented poet and painter Whitney Claflin’s language-based game Impulse, which comprises cards featuring a stock of words and phrases she first collected in 2011 and has been constantly evolving ever since. While Claflin could not be physically present for the demonstration of the game due to a knee injury suffered on election night, Mallett acted as a surrogate, shuffling, delivering, and dealing yellow prompt cards and white response cards. Viewers got close ups of the cards’ words via live-feed camera while Claflin’s soothing monotonous voice recording recounted both instructions for the game rules and a first-person narration of how the game might take on personal and political meaning. The audience gasped or laughed as they watched the overhead projector present cards reading “pi,” “Morpheus,” “American Apparel underpants,” and “Burning Man.”

Players were to match a choice from their hand of white cards with the yellow card in center, like a less lewd Cards against Humanity. No one won, Claflin explained, but during each round, someone would judge whose matches were best, and the winner would take that yellow card. Perhaps those words said something about that person, Claflin suggested. The game was also a kind of historical artifact—showing the way words and associations can so readily mutate and evolve. In one particularly fitting demonstration, the prompt of “retro” was paired up with phrases culled from different cultural imaginaries from the past decade such as “self-driving car.” What was once contemporary or considered futuristic becomes a slice of a previous moment. Volunteers played a couple rounds, and the audience got to vote on the winners. Impulse invited a collective untangling of language and time.

“The library’s function has become even more urgent given current far-right assaults on library systems—where collected objects of knowledge and history constantly are recontextualized within and outside, leading to newly invented or revived ideas of what community is.”

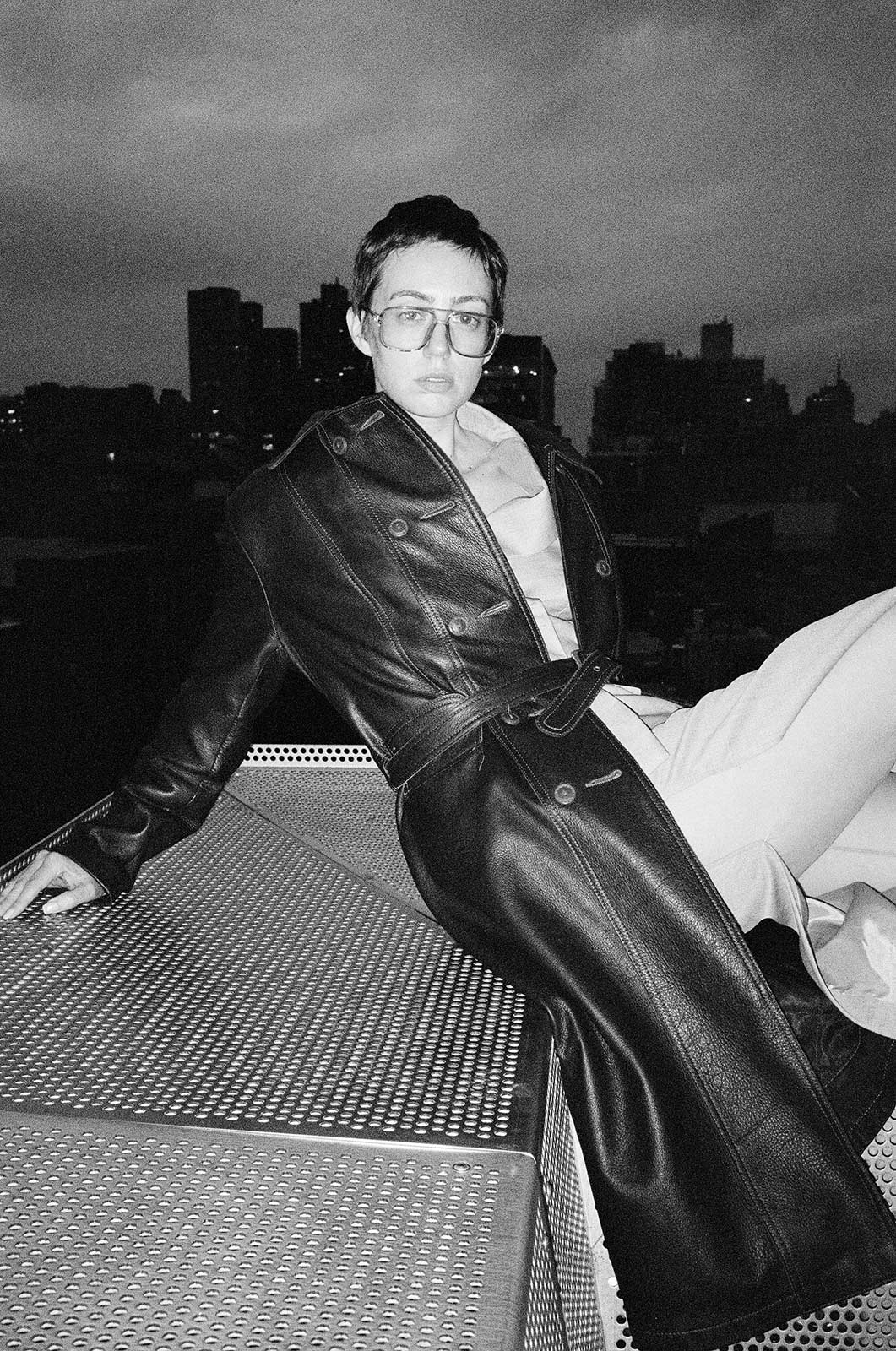

A collaborative theatrical performance by poet Maya Martinez and deputy editor of The Whitney Review Mani Mekala Rajagopal followed Claflin’s performance and made extensive use of the stage props. In pencil skirts and cleavage-bearing oxford shirts provided by rising indie brand Shame, Martinez and Rajagopal embodied a sexy librarian fantasy, guiding an imaginary visitor through this deconstructed library as a site of larger-than-life glamor, desire of dubious legality, and esoteric secrets. Engaging in a teasing exchange with an unseen guest, these librarians opened the towering cabinets behind them, reading files that hinted at hidden truths of this world, with subject matter ranging from the space shuttle Challenger disaster to watt-hours consumed by generative AI to Ozempic side effects. Fictive statements such as “Did you know all holes in the body are capable of breath?” appeared in the files periodically, suggesting that the library is porous, often exceeding or resistant to the full control of human intervention and organization. They began to bicker, then got into a physical fight over who was better suited at guiding the mysterious, absent visitor to absolute knowledge. The performance ended with the two making up, oversharing and reveling in conditions of suffering and insufficiency. According to Martinez, the performance is about the radical alterity of the library as an impossibly grand endeavor of classifying and taxonomizing human knowledge: “Maybe there is not one piece of knowledge that can answer everything. What if there are no answers and only others?” Martinez and Rajagopal asked us to suspend our disbelief and delight in shadows of doubt.

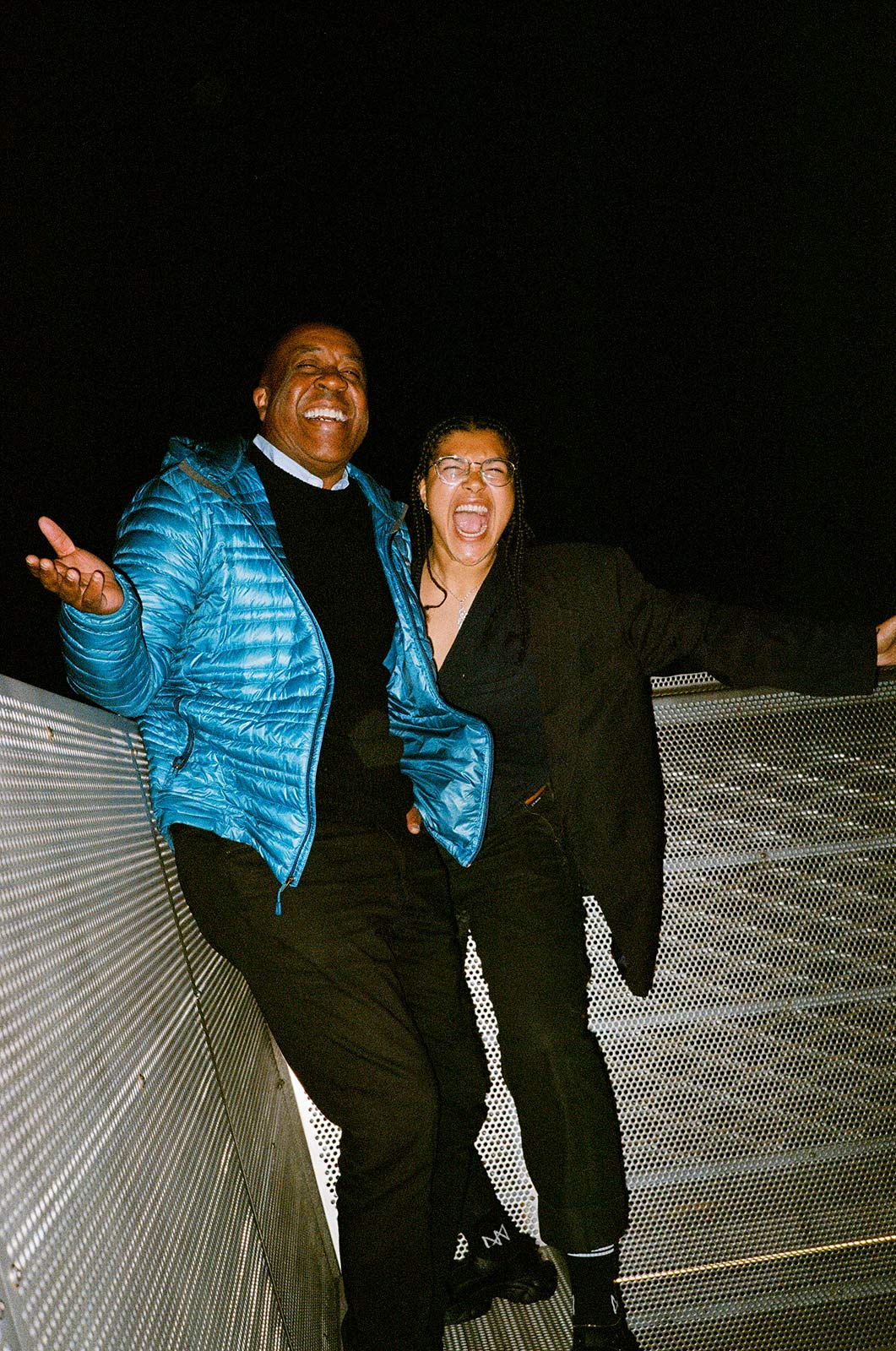

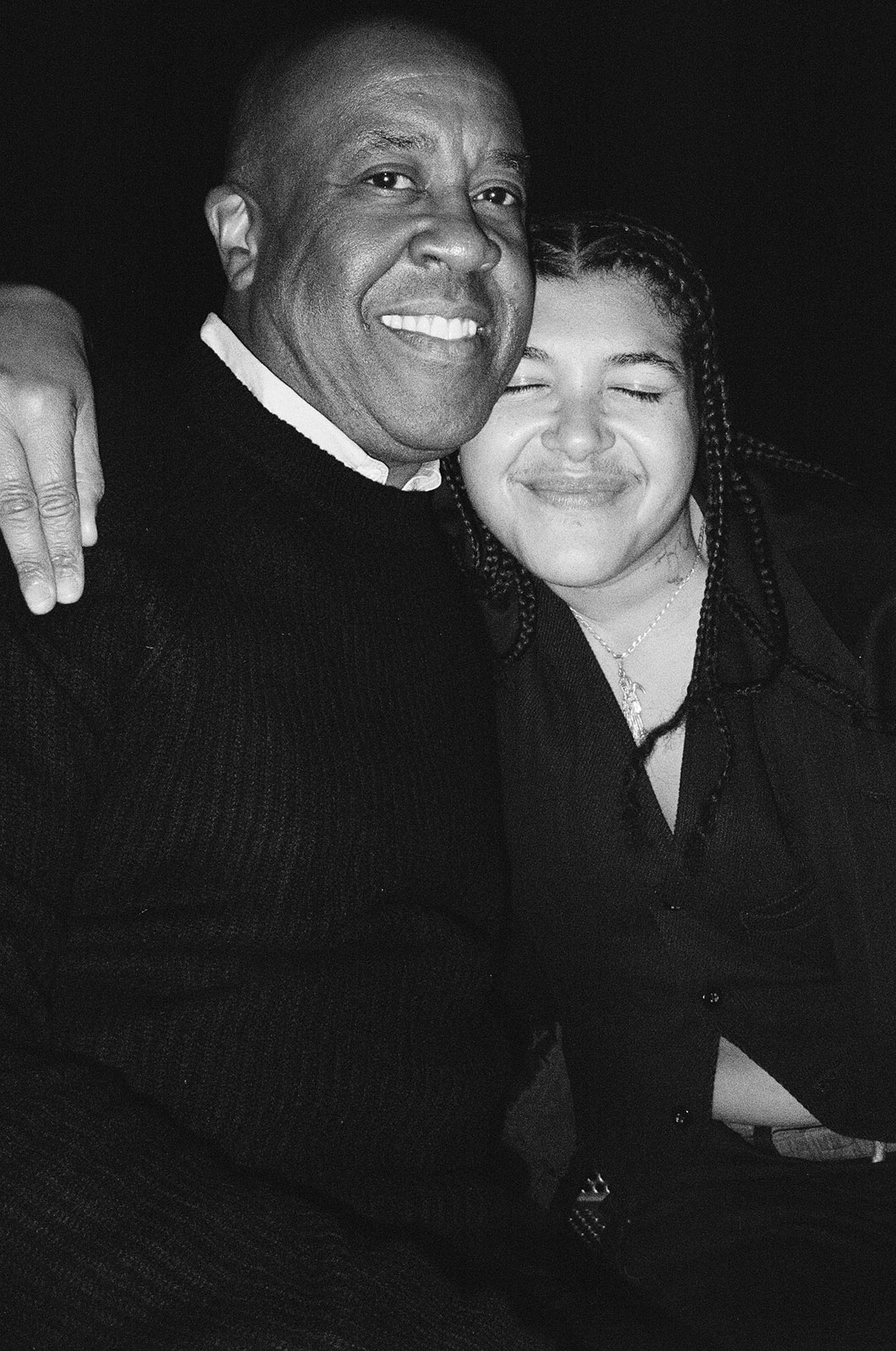

The final act presented a more personal version of archival reading. Stagehands brought out chairs and decorative plants to turn the deconstructed office into a set reminiscent of a daytime talk show. Out walked writer and artist Esmé Naumes-Givens and their librarian father David Givens. Their live conversation revisited childhood diary entries and a playlist their father made for them when they were 11, paying sensitive attention to how certain episodes—Naumes-Givens’s appreciation for Ye, for example—might gain new meaning given current social or political context while others continue to evoke tender, cherished memories of adolescence.

Throughout LIBRARY, artists erected various allegorical or fantastical presentations of the library. They suggested the library as a refuge when collective intellectual endeavors are under threat from manufactured precarity. For one night at Performance Space, we were invited to experience the library as a place between mythology and fact, awaiting its actualization of reading in communion in each mystical promise of liberation. Throughout the process, we came to understand the library not as a celebrated site of democratic participation but as a more-than-human agent, capable of evolving and adapting to and against popular taste, however clumsily and awkwardly. It mirrors and reflects our own archival impulses and desires for transcendence. LIBRARY moved us through the future, present, and past, reveling in both revelation and obfuscation while taking us to the limits of language, knowledge, and reality.