For Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue, the filmmakers ruminate on the transportive power of cinema, the art of interpretation, and the importance of honoring your audience

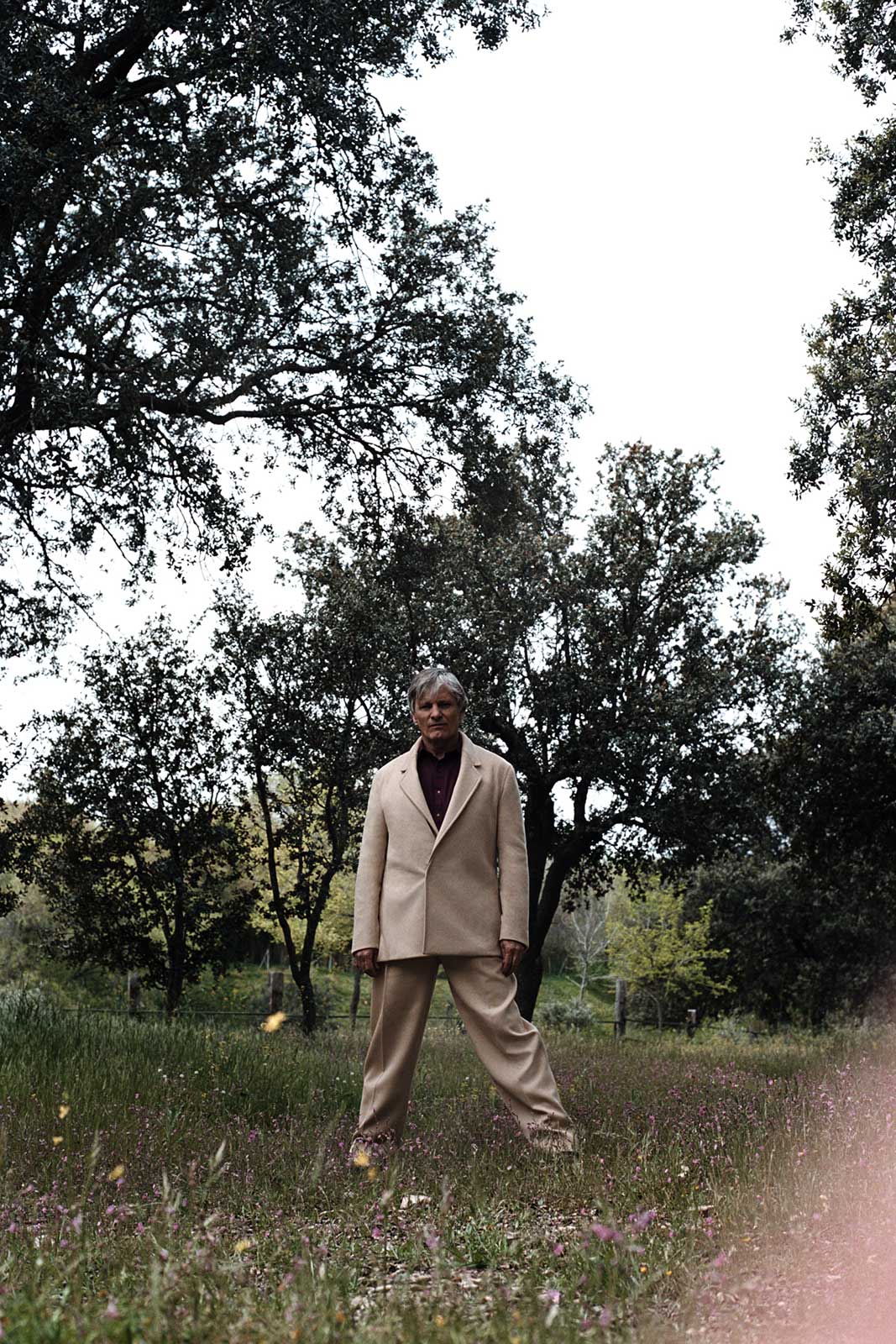

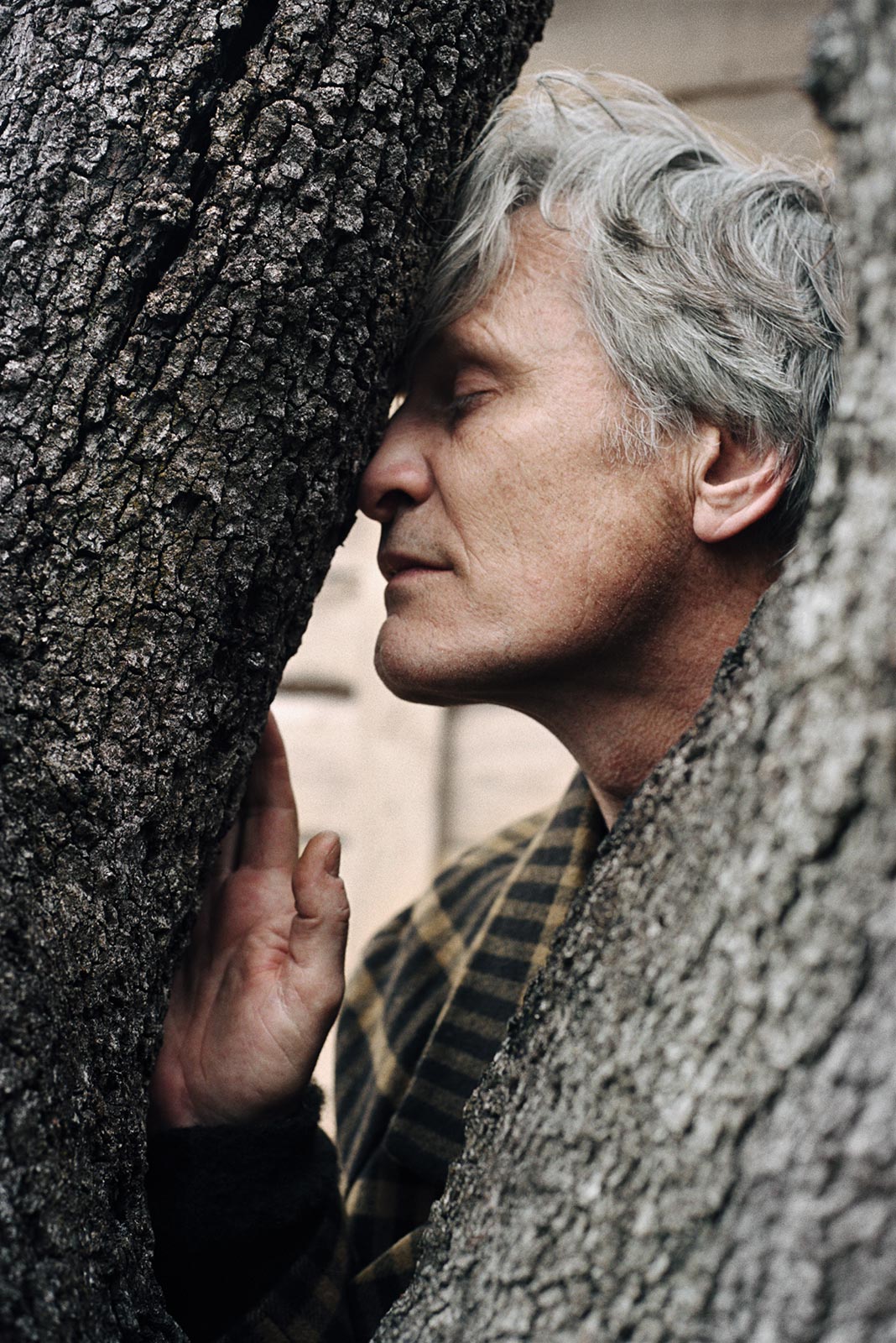

Viggo Mortensen plays characters who flicker between violence and vulnerability, revealing interiorities that complicate even the most extreme instincts. In A History of Violence (2005), the actor portrays Tom Stall, a small-town restaurant owner haunted by his mafioso past: a man who never moves until necessary, yet transforms into a hardened criminal when called to act. Faced with a threat, his affect changes like a cloud blotting out the sun; after unleashing unimaginable brutality, the sky clears again, and he turns back into a wholesome family man. In Eastern Promises (2007), he’s a menacing yet enigmatic fixer with ties to London’s most dangerous crime family. However, he’s driven by a mysterious moral compass his compatriots lack, even if it fails to prevent him from hacking off limbs or killing opposing mobsters in a nude fistfight. In 2022’s sci-fi body horror Crimes of the Future, his character’s interiority is quite literally put on display, with Mortensen embodying the role of a performance artist who grows new organs in his body only to have them surgically removed in front of rapt audiences. But he’s just as capable of concealing as revealing: As Sigmund Freud in the historical drama A Dangerous Method (2011), animus simmers behind the psychoanalyst’s clinical detachment. With Mortensen, still waters run deep—and he channels this potent emotional undercurrent in his directorial debut Falling (2020), playing a gay man embattled by psychological attacks from his mentally declining father. In his second directorial project, The Dead Don’t Hurt (2023), Mortensen—who acted in the Westerns Appaloosa (2008) and Hidalgo (2004)—returns to the American frontier, telling the story of two star-crossed lovers torn apart by the Civil War. Acting opposite Vicky Krieps, Mortensen exudes a quiet intensity as Holger Olsen, a disillusioned cowboy whose tenderness toward those he loves is exceeded only by the force required to protect them.

Mortensen wrote, directed, starred in, and created the score for both Falling and The Dead Don’t Hurt—a feat that highlights his multidisciplinary talents, which also include photography, painting, poetry, and publishing. But while the stories were born largely from his imagination, Mortensen hardly goes it alone. Rather, he sees storytelling as an act of collaboration and solicits ideas from cast and crew to forge a “complete cinematic world” as multidimensional as its creators. “Collaborating can take you outside of your comfort zone, which is why some directors resist. The movie becomes not your movie. But there’s always going to be a piece of you in any story you tell,” he reflects. “You never know where a good idea can come from, or from who.”

Ron Howard—whose six-decade cinematic career has spanned numerous genres, earning him two Academy Awards, four Emmys, two Golden Globes, and a Grammy—couldn’t agree more. The communal nature of storytelling is central to his approach, having discovered as a young director that his creative vision was strengthened by the inclusion of alternate perspectives. This proved essential when shooting Thirteen Lives, the 2022 biographical survival drama on which he and Mortensen collaborated. Based on the true story of the Tham Luang cave rescue, the film depicts the mission to save the lives of 13 young boys trapped underground—accurately capturing not only the narrative but the nuances of Thai culture and language with the help of its crew. It wasn’t his first time adapting a real-life story: From A Beautiful Mind (2001) and Cinderella Man (2005) to Frost/Nixon (2008) and Apollo 13 (1995), Howard—who got his start as a child actor in the television sitcoms Happy Days and The Andy Griffith Show—merges biographical details with imagination to present gripping narratives that encourage audiences to think in new ways: “You try to be truthful in the spirit of the events they’re based on, but you’re using them as tools to change people’s perspective.” This, he says, is the promise of filmmaking: to engage you, to entertain you, and ultimately, to transport you.

“I like to be respected as an audience member. I don’t like to be spoon-fed things: It’s what’s said and what’s not said, what’s shown and not shown, that has equal weight.”

Ron Howard: Hey, Viggo.

Viggo Mortensen: Hey, good to see you. I’m going to join you and get a ball cap too. [Viggo puts on a ball cap to match Ron] Where are you?

Ron: I’m in LA. I’m acting this week, but it barely counts because I’m playing myself. It’s for a show called The Studio, where Seth Rogen plays a studio boss.

Viggo: Is he your boss?

Ron: He’s my boss in this, and I don’t love that about him. [Laughs] I feel rusty. But I think I know my lines. It’s been about 35 years since I actually had to memorize anything.

Viggo: It’s like riding a bicycle. I remember the first movie where I got to ride a horse, Young Guns II [1990]. I had grown up riding horses, but I don’t think I’d been on a horse for 20-some years. I was a little nervous about it. But after I got on, I was like, Wow, I really like horses. I remember this, I like it! If you like doing it, it’ll come back to you.

Ron: I remember [director] Joe Johnston said you were such a horse man. What was that amazing movie that you guys did together?

Viggo: Hidalgo. By then I was back into it. For the movie I’d made before that, The Lord of the Rings [2001–3], I got to ride a fair amount. And the more different horses you ride, the more you learn to be flexible and to adapt—just like the more movies you’re in as an actor, or the more stories you tell as a director. You learn that every director is different, every actor is different, and every actor’s different on every day.

Camille Sojit Pejcha: You both started as actors and expanded outward to other forms of storytelling. How did directing influence how you see the actor’s role within a project?

Viggo: I’ve always been curious about the process and how it all works. If I was allowed, I would hang around set on days when I wasn’t working as an actor. I quickly realized there was more to it than just what was on-screen. There were a lot of people with different skills. And I could see that if everybody compromised a little bit on their own personal desires and point of view, it became a true collective effort.

I was just as nervous the night before starting shooting as a director as I always was before starting shooting as an actor. The one difference was that instead of being a nosy actor asking people questions on the set, I was being asked hundreds of questions every day by other people. And it’s important to take them seriously, these ideas from the cast and crew. You never know where a good idea can come from, or from who.

If the team on set feels that what they have to offer is of interest—that they’re not just punching the clock and adding their particular skill, but that their opinions matter—they’ll get more involved, work harder, and take the storytelling personally. That’s the ideal, when everybody feels like they’re doing something special.

Ron: I call it ‘the six-of-one rule,’ meaning six of one, half a dozen of another. You want that engagement. I started to realize that when someone presented an idea—which means they owned it and loved it enough to take that leap and mention it to the director—there’s an intangible X-factor to their ability to execute that. And if it works, it may elevate the story.

I directed my first movie when I had just turned 23. I was prepared, I was well-organized, but I was afraid to take anybody’s advice because I thought it would show weakness. I began to realize that my work was limited to my imagination. It took me a couple of tries before I recognized how much other people could contribute. My work took a giant leap when I began to accept that, and became excited about it, and realized that it wasn’t a demotion of my authority. Now, I’ve built my entire way of working around that. I’ve learned from them, they’ve learned from me.

Viggo: That’s a great feeling. I’ve worked with some directors who take this ‘my way or the highway’ approach. They don’t have to be rude about it for it to be clear that there are no suggestions, they’re blocking everything, you’re just a pawn. I believe that even the great films that have been made with that approach would have been better if they had included the crew and made people feel like they had ownership, a little piece of the story-telling. It’s a team sport, ultimately.

The other thing about movies is that it’s a complete creative universe. There’s no art form that’s not potentially involved! And collaborating can take you outside of your comfort zone, which is why some directors resist. The movie becomes not your movie, even if you’ve written it and are directing it. But there’s always going to be a piece of you in any story you tell. You are the product of all your experiences in life from childhood to right now. And that affects anything you do as a director, as a screenwriter, as a cinematographer, in any creative endeavor. I just assume that everything I’ve seen and done—everything I’ve been exposed to in life, including movies—is going to affect any performance I give. No matter how far the character seems from how I appear to people—or to myself, even—there’s always going to be a part of me in there.

I’ve been asked, ‘What was the audience you were thinking of when you made this movie?’ The answer is, I was making the movie for an audience of one. I was making the movie for myself. And I don’t mean that in a selfish way—I was trying to make the kind of movie I’d like to go see, and hopefully other people would like to see as well. In the end, as soon as I show the movie to you or anyone else, it’s no longer my movie, it’s yours.

I like to be respected as an audience member. I don’t like to be spoon-fed things: It’s what’s said and what’s not said, what’s shown and not shown, that has equal weight. When I’m watching a movie, something about it has to get me involved—the way it’s shot, the tone, the acting, the landscape. Even if I’m not quite sure where the story’s going, if there’s something attractive to me in the first 15 minutes, I’ll stay with you. And then if you give me enough to go on, I’ll stay with you all the way—I’ll take the information I’m given visually and aurally, and I’ll start putting it together myself.

Camille: It sounds like you’re almost giving people the tools to create their own story—making them your collaborator in a sense.

Viggo: Absolutely. You’re giving them just enough. Then it’s like, Build your own movie from here on out. You take part as well.

I remember during the pandemic, every day I tried to watch a movie that I hadn’t seen in 20, 30, even 40 years. I’d think, I remember really liking that movie. I wonder if I still will. And sometimes I liked them as much or more. And sometimes I was surprised: Why did I like that? Movies change every five years as you see them again, because you are changing. It’s the same with each audience. When a movie’s being released, I like to watch all or a large part of it at each screening. Sometimes, I’ll stay the whole movie. It’s like, Oh my God, I can’t believe I’m watching the whole thing again. But there’s something in that room that makes the movie different, that slightly changes how you see it.

Ron: And you never know how a story is going to land with people at various points in their lives, who’s going to connect with it or why. You have your viewpoint, your sense of what this narrative might mean, but it’s an invitation for people to connect with it on their own.

I had a chance to act with John Wayne in The Shootist [1976]. I asked him a lot of questions about John Ford, who was a real favorite filmmaker of mine. I said to Wayne, ‘When you directed The Alamo [1960], did he have any advice for you?’ And Ford [told Wayne], ‘Only take anything 90 percent there, whether it’s emotion or comedy or action, you want the audience to finish the final 10 percent their way.’

Viggo: It’s not a monologue, it’s a conversation.

Ron: When you shifted to working behind the camera in Falling and The Dead Don’t Hurt, I’m curious how you navigated directing the actors in the scene with you. Because you’re not a personality actor, who just says the lines one way. You go fully in, psychologically.

Viggo: Well, first of all, as an actor, Viggo’s pretty obedient and efficient. And he listens to the director. [Laughs]

In a strange way, it makes it easier because you’re doing what you should always do as an actor. I don’t have time to get self-conscious. I’m looking at you, the person who I’m acting with. Everything about your face, your voice—the tone, the timing, the pauses, everything you see and hear within that space. And that’s exactly how you should be as an actor: receiving, not imposing. But we’re human and we’re vain or paranoid or self-conscious, no matter how polished you are.

Even when I’m on set and I’m not acting, I try not to spend too much time looking at playback. You want to keep moving and keep the actor’s engine running. I only look if I’m in doubt, or if the cinematographer says the shot’s out of focus or the camera moved.

Ron: And that’s part of the excitement of live-action production. I’ve worked in animation too, and one of the things you think about with AGI [Artificially Generated Imagery] coming down the road is that it’s going to be a new iteration of the medium. Because there’s still going to be a difference between AI-generated characters, whether that’s bringing John Wayne back to life in a movie or doing something fantastical. Once that tech is in a place where you can control it enough to make a whole movie, there will still be something intrinsically interesting about knowing that this is a human, bespoke, handmade movie. And that’ll be an aesthetic.

Viggo: It’ll be a different genre. Like comparing opera to theater. When you were starting out, were there actors and directors that made you want to do it?

Ron: So many. Dustin Hoffman mesmerized me. I had to see every Sidney Poitier movie. His eyes, the way he was so focused. And then Meryl Streep was incredible, but so was Warren Beatty. It was an era where stories were really built around acting more than anything else. But my primary experience was with television, which was very formulaic in those days. So I had to discover movies more as a fan than anything else. I was going to the movies to go on a ride and a journey, and I never felt that way about watching a television episode.

When I acted in American Graffiti [1973] for George Lucas, it was completely mind-blowing, because he created a world. So much attention to detail, but not in a controlling way—it’s more what we did on Thirteen Lives. He created this environment, and then he kind of let the scenes happen within it. I was a little disoriented by it at first, but when I saw the movie, I realized that he was creating an experience for an audience. It wasn’t just telling a story. I realized, Oh, this is where cinema is going. If I want to be a filmmaker, this is another way of understanding how a story gets told and its potential.

Viggo: My mother was the first one who took me to the movies, and we would always talk about the story. At a certain point, I went from watching to wondering how it’s done. What’s the trick? Why is it that, afterward, I’m surprised when I walk outside and I’m in Manhattan, not the Sahara Desert? It’s in winter, not summer, or it’s not night, it’s day? Why am I moved to tears, or why am I suddenly thinking about somebody in my family? It’s not just that I like this movie. I’d always talked about movies with my mom, and I love stories, right? But I thought, Okay, the thing that’s moving me is what this actor is doing. I’m going to try to find out what that is. I had just moved to New York, and I literally looked up a theater workshop in the yellow pages. I had no idea! I went in and said, ‘I’m here to try out for the play. I want to audition, what do I do?’ And they said, ‘Well, bring back two pieces next Monday at 8pm.’ I said, ‘Two pieces of what?’ [Laughs]

I knitted together a monologue from a short story about Jack the Ripper by Isak Dinesen. And then there was a song I liked—this Irish song, a couple hundred years old, about this guy who’s forced to join the British Army and hates it. I came and I did this monologue that I put together from a short story, pretending I was Jack the Ripper, and then I sang this Irish song. And for whatever reason, they said, ‘Okay.’

It goes back to what my mom talked to me about when I was a little kid. She’s a woman of her time, housewife, mom of three kids. But I think she could have, in another life, been a screenwriter or director. It was always about the story. I remember being four and going to see Lawrence of Arabia [1962] with her in one of those big theaters where you had intermissions. We would sit in the front row, right in the center. And I always did that with my son, too, when he was little. You want to be in the movie.

Up to the end of her life, until she couldn’t go to the movies anymore, if I would visit her or she was visiting me, it’d be, ‘You want to go to the movies?’ ‘Yeah.’ And even if it was a bad movie, there’d be something that we found interesting that we talked about.

“You prepare as much as you can, but then you have to adapt and overcome. You have to get lucky with the story and what happens that day. But you can prepare for luck.”

Ron: Do you ever have that experience of seeing a movie and being so blown away by it that you just didn’t leave the theater and they didn’t kick you out and you just got to see it again?

Viggo: I did that when I saw Taxi Driver. There were only a few people there, because it came out in ’76, and this was in 1982. I remember I was stunned by that movie, and I did stay sitting there, just thinking about it. And then people started coming in and I thought, I’d love to see it again. Maybe they won’t notice. They didn’t. I watched it twice.

I also worked in a movie theater when I was first starting acting in New York City, and it was a revival movie theater.

Ron: Which one?

Viggo: It was the Thalia up on 95th and Broadway. At that time, it wasn’t as gentrified as now. I got held up twice by junkies with guns. The job was ‘sell the ticket, turn around, sell the popcorn’—one-person operation, right?

I just wanted to see stuff, as you do when you first get excited about acting. I was going to plays, too… ‘Second acting.’ I don’t know if you can still do that, but when people are milling around and standing outside at the intermission, you just walk in with them and when the lights go down, you just find a seat and watch the second half. So I saw the second half of plays for free many, many times. It didn’t matter what it was, musicals, whatever, you’re just soaking up everything. You can’t see enough.

Camille: You’ve both worked on a lot of projects based on true events. How do you see the relationship between real-life experience versus imagination in your approach to storytelling?

Ron: It depends on the reason you’re making the film. There’ve been films that I’ve made based on real events that were real, and the goal was just to show it: Here are these things that happened, and you just need to understand them in as authentic a way as possible. That was Thirteen Lives, that was Apollo 13.

With other films inspired by real events—A Beautiful Mind or Frost/Nixon—you can take more liberties. You try to be truthful in the spirit of the events they’re based on, but you’re using them as tools to change people’s perspective about something. Do you need to adhere to the details of the events, or are you just capturing the spirit, building upon it to create a narrative experience for the audience?

Viggo: What is essential to keep the story moving forward? What are things that are going to up the stakes for the characters involved? I think of A Dangerous Method, a David Cronenberg movie where I play Sigmund Freud. There are conversations between Freud and Jung that Christopher Hampton wrote. There are certain liberties taken, but it’s based on deep research about how they interacted, using dialogue and jokes as a way of showing their competitiveness or rivalry. Who knows if it actually happened exactly like that? But it feels like it might have.

Ron: The big difference is your relationship with the audience. In a documentary, the audience is much more patient; they’re leaning in, curious, they wouldn’t be there if they didn’t want information. But with any scripted project, people want to be entertained. ‘Engage me. Take me on the journey.’ You’re still trying to convey a truth, an insight, but the promise to the audience is different.

Viggo: The details make you believe it, whether it’s a completely fictional story, straight documentary, or a docu-fiction. Objects, props, and landscapes—they are characters in a way, too. And the more specific you are about something, the more you have a chance to appeal universally, whether it’s with language, behavior, or the details of the objects that you see.

In The Dead Don’t Hurt, for example, it’s a completely made-up story. I didn’t want to reinvent the Western. I wanted to make a movie that I would like as much as say, Red River [1948], one of the good old-fashioned Westerns I watched growing up. And it was so much fun. When I was in Australia shooting Thirteen Lives, I found a video store in a nearby mall that was selling all their DVDs. There were hundreds of Westerns—all the movies I’d seen as a kid and 150 more. It was a closeout sale. And I said, ‘What price would you give me if I bought the Westerns?’ They go, ‘Which ones?’ I go, ‘All of them.’ I did several trips, two or three big bags at a time. On weekends I’d get takeout, and I’d watch four in a day. Then I started making notes.

The research for a movie can be as much fun as the actual shoot—sometimes more fun. You just never know what’s going to happen. You prepare as much as you can, but then you have to adapt and overcome. You have to get lucky with the story and what happens that day. But you can prepare for luck. If you’ve got a lucky break and you’re not prepared for it, you might not even realize it!

We made The Dead Don’t Hurt as accurate and as faithful to the classic Western tradition as we could—but one thing that makes our story different is that there’s a woman at the center of the story. That’s not what you usually see in classic Westerns. And certainly, you don’t stay with the woman when her male partner goes off to war. You usually go with him, and then you come back and she gives him a big hug, or she’s dead or something, but you go with him. In The Dead Don’t Hurt, we stay with her.

Ron: That’s one of my favorite sequences in the movie. I love Westerns, and I love my Westerns realistic. The Dead Don’t Hurt is so strong, and it feels so honest. I’m not surprised about all that research you did because, man, it feels like you’re there.

Viggo: On Thirteen Lives, you had people who had actually been there. And so they could say, ‘I understand why you’re skipping this, but what you’re doing is very much in the spirit of the argument we had on that day.’ I imagine the same is true on Apollo 13.

Ron: I remember when preparing for Apollo 13, we were doing what they called the ‘Vomit Comet,’ which was an airplane that would do these parabolas, and as it would dive down, you’d go weightless for 23 seconds. It’s one of the ways that NASA trains and tests certain procedures. And the astronaut Jim Lovell gave us the idea that we could achieve weightlessness in there if the government would allow us. We had to take our Air Force physicals, we had to go through training, we had to go through a test run so they would see that we weren’t flakes. It was physically demanding. And we would do two days in a row, two flights each day. Each one was about two hours, about 40 or 50 parabolas per flight. Years later, one of the real astronauts was asking Tom Hanks about it, and he explained our regimen. And he said, ‘Oh, we never did two days in a row. That thing beat the hell out of you.’

Viggo: ‘You guys are crazy.’ [Laughs]

Grooming Joe Burwin. Photo Assistants Steve Pane, Olivier Peresse. Stylist Assistant Irene Monje. Production Director Lisa Olsson Hjerpe at CHAPEL Productions. Local Producer Adriana Suárez. Production Assistant Karim Lemrini. Location Granja El Álamo. Casting Director Tom Macklin.