For Document’s Fall/Winter 2023 issue, the actor breaks down the art of keeping out of rhythm and seeking comfort in destiny

September 2023, the Burberry show at London Fashion Week. It’s Daniel Lee’s second full collection for the brand and there’s still plenty of buzz. The show is oversubscribed and laden with Britain’s beautiful elite. Fashion show attendees are not unlike antelope at a watering hole: delicate in their movements, hyper-aware and pack-minded, conscious that one step out of line can spell disaster. But here comes Barry Keoghan.

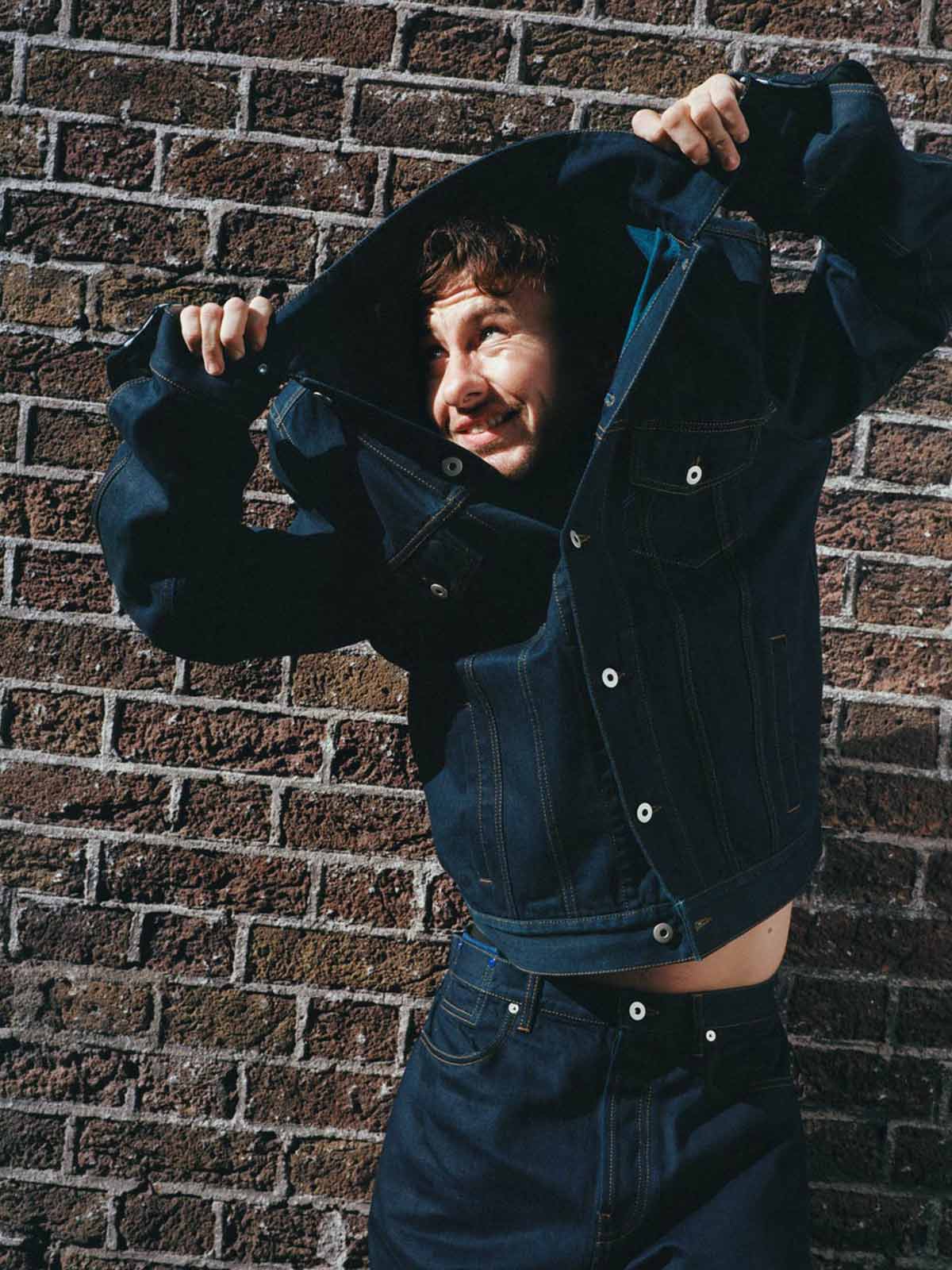

The Irish actor prowls and leaps, scampers from the step-and-repeat to the FROW and back again, grabbing former co-stars in a brotherly embrace, giggling with the door staff, coquetting with photographers. He is dressed in a baggy black-and-white houndstooth Burberry tracksuit, occasionally lifting the collar over his nose so only his impish, ice-blue eyes peek out. Hair cropped short, pearl-set rings worn curiously between the middle knuckle and nail of each index finger.

Young actors, now so often found at shows like this, tend to wilt in the glare of big fashion. They shift awkwardly in clothes they wouldn’t normally wear, jostle politely for ever-decreasing space on the bench, and feign fascination as models glide past. But Keoghan relishes in it, beaming and wide-eyed, drinking in the baffling pomp of it all, as if he’s up too late and at any minute, someone’s going to send him to bed.

“I was a messer, always looking up at the stars.”

“I always loved wearing what I wanted to wear,” he tells me, a few weeks after the show, “and not following the dress code of the lads. When I was growing up, you wore the North Face that everyone was wearing. I’d try to wear the denim jacket.”

That place Keoghan comes from is Summerhill, a neighborhood just north of the center of Dublin. In the 18th century, it was known for coachbuilding. Then, for tenement housing and the Monto red light district. Today, it’s a tough place to live. One former Dublin resident describes it to me as “the most notoriously dodgy” area of the city—which may not be a fact, but perhaps isn’t far off. Keoghan says acting aspirations are unusual in Summerhill. “Even to finish school is massive,” he explains. “Not to say where I come from, nobody finishes. But it’s still a big achievement. I [didn’t] do so well in school. I was a messer, always looking up at the stars.”

Keoghan’s time in Summerhill was perhaps defined by his mother’s struggle with addiction. He and his brother were in and out of foster care for years. When he was 12, she tragically passed away and they went to live with their grandmother. “My mum never knew I was into acting,” he says. But, he supposes, maybe she supposed he might be, as he danced to cheer her up while visiting her at the hospital, and that she knew he was destined to be a performer.

Much to his grandmother’s relief, Keoghan was one of the Summerhill boys who did finish school, but by then, he’d already decided he wanted to be an actor. In what has become a much-repeated, perhaps apocryphal tale, at 15, he saw a poster in a shop window offering open auditions for an independent film—Martin O’Connor’s Between The Canals—and something clicked. Keoghan didn’t have enough credit on his phone to call the number, so he used his grandmother’s, but was told the production was delayed waiting for finance. That, of course, meant nothing to the teenager. He just wanted to be paid to skip school, maybe ride his dirt bike around in the background of a movie. So for months, he kept calling, kept checking he hadn’t missed his chance. Finally, O’Connor called him back.

“I like the unrhythmic—just being, just behaving. Solely being in it, responding to the other actors, [and] just listening. Not having preempted behaviors or emotions ready to fire off.”

Fifteen years later, Keoghan is one of the most beguiling young actors in Hollywood. A breakthrough performance alongside Colin Farrell and Nicole Kidman in Yorgos Lanthimos’s The Killing Of A Sacred Deer (2017) made his boyish, handsomely hangdog face recognizable in Christopher Nolan’s cameo-laden war epic Dunkirk. Then, he started popping up all over the place: in HBO mini-series Chernobyl, in Nick Rowland’s grizzly debut Calm with Horses, and in Marvel’s TV spin-off, Eternals. Last year, Keoghan picked up where Joaquin Phoenix left off in a tantalizing, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it turn as the Joker in Matt Reeves’s The Batman, and then stole the show as lovable fool in Martin McDonagh’s The Banshees of Inisherin, for which he was nominated for an Oscar and awarded a BAFTA. That placed him firmly at cinema’s top table, but only now does he appear in a lead role, in Saltburn, Emerald Fennel’s lurid tale of English class, teenage longing, and human deceit. He has been busy, or making up for lost time. Really, he’s only just getting started.

On the internet, Keoghan is listed as having studied acting at The Factory, a drama school in Dublin. But if you ask him, he’ll say it isn’t true. Not in the traditional sense, anyway. Today, it’s the Bow Street Academy—Ireland’s national screen acting school. Back in the mid-2000s, he says, it was much less formal. He’d bunk off school and stop in, still wearing his uniform, to watchh old movies (Cool Hand Luke, On The Waterfront) and documentaries, play around with cameras, and workshop random scenes. “We’d be experimenting,” he explained in a January interview for the podcast In The Envelope, “bringing in scenes we’d printed off the internet, and all throw in a fiver for the heating.” It was more of a freeform actor’s studio than a school, he says, remembering being asked to stay in character for days at a time, just to see what it was like.

Keoghan is wary of the tenets and rules formal drama schools can instill in young actors, preferring instead to foster what he calls rawness. “I like the unrhythmic—just being, just behaving. Solely being in it, responding to the other actors, [and] just listening. Not having preempted behaviors or emotions ready to fire off.” It’s meditative, he says, nauseating at times.

On the set of Between The Canals, Keoghan realized that rawness for the first time. Rather than putting him on the back foot, the feeling of unknowing lingered as a potential strength. “You need to have that muscle to learn your lines, to hit your spot,” he says, describing how drama school can only get you so far. “But in terms of a performance, I’m always trying to go back to my first time on camera.”

In 2017’s The Killing Of A Sacred Deer, He plays Martin, the film’s villain and figure of pathos: a lost and lonely boy, a parasite. His performance stole the whole movie, and it was completely unrhythmic. But it set him on a path rich in work but perhaps lacking in variety, emerging as Hollywood’s foremost aloof, menacing lad.

In A24’s fantasy epic The Green Knight, for example, he plays a duplicitous scavenger, charming at first but diabolical after all. In Calm With Horses, he plays Dympna, an angry orphan searching for belonging in a world of hyper-violence. And last year, there was the Joker—pop culture’s ultimate troubled young man.

It means he’s hyper-selective now—a luxury, he admits—and only considers work that offers him the chance to learn something new, to be cast in a new light, or, ideally, both. “I get offered to play parts, and [some] I have to turn down, because it’s like, I’ve done that,” he says. “I’d work less for better quality, if that makes sense. Every project, I give my entire self to it.”

Would he do a rom-com? Or a Bond movie? “If it speaks to me, if the filmmaker is someone I admire. I don’t mean to be formal here, but it depends on the character. It depends on what it’s going to do for me when I read it.”

The Banshees of Inisherin, then, came at the perfect time. On paper, Dominic Kearney is another lost, lonely boy, but he’s funny too. Really funny. And crucially devoid of malice. Dominic is a palette cleanser for all the movie’s bloodshed and gloom, its moral compass, and in a small way, its hero. The film was nominated for almost every award going and it was Keoghan’s pivotal scene with Kerry Condon that lingers, still doing the rounds on social media a year later. “Well, there goes that dream…”

This resonance is what Keoghan strives for in his work. “I don’t want people to have me figure [a film] out [for them]. I want people to leave thinking about it for a few days. I think that’s the beauty—that’s what I love when I leave a movie.”

And so to Saltburn, where Euphoria meets Brideshead Revisited. In Emerald Fennell’s follow-up to her lauded 2020 directorial debut Promising Young Woman, we meet Oliver Quick, a Northern boy set adrift in the grasping, class-obsessed maze of Oxford University in the mid-2000s. On a scholarship, he won his place on pure merit but soon realizes that he is simply not cool enough, not beautiful enough, and not connected enough to ever fit in. But Felix Catton—the most handsome, mesmeric, aristocratic student in the whole school—takes a shine to poor Oliver and opens the big oak doors to a world that high society would have never allowed him to even know existed. Skullduggery ensues.

Keoghan is perfect as Oliver. The film is a slow, sardonic burn that eventually erupts into an elongated, eye-watering crescendo, and he grows with it, bolstered by brilliant performances from the likes of Rosamund Pike and Alison Oliver. But this is new ground for Keoghan. A lead role, finally, and also one that stretches him in all directions. His physicality is tested and so is his presence, his capacity to hold your attention past the punchline, and ultimately, his commitment.

Saltburn will be a hit and rightly push Keoghan into rarified air. But 13 years on from that first movie, he still thinks of himself as being new to the game. There is a touch of detachment in the way he speaks about his career, almost as if it’s been happening to him. There’s a sense of a hidden force pushing him along, or at least letting him know he’s in the right place. That force, he thinks, might be his mother.

In American Animals, Bart Layton’s 2018 heist movie starring Keoghan as a hapless book thief, a slick montage scene is set to Elvis Presley’s “A Little Less Conversation,” the song that Keoghan danced to for his mother in the hospital all those years ago. And while choosing his character’s accessories from the prop table on another production, he was drawn to a bracelet which turned out to be engraved with his mother’s name, Debbie.

“I don’t believe in God, to be quite honest. I do believe in hard work. If you want to succeed in having that experience, [playing] that part, committing to that energy works.”

I ask if he believes in destiny. “Definitely,” he shoots back without hesitation, before clarifying: “That’s not to say I believe it’s [the case for everyone], but it gets me by. It’s my comfort.”

He’s a big believer in manifestation, too, and though he may be at a stage in his career where roles come somewhat gift-wrapped, he has hustled in ways most actors wouldn’t dare. There was the tweet he sent comic book icon Stan Lee in 2013, begging to be made a superhero, which he often credited (jokingly, but not that jokingly) to his casting in Eternals. And then there was the unsolicited self-tape he made for The Batman director Matt Reeves demonstrating, he hoped, his suitability for the role of the Riddler. He even published it online for maximum exposure. Paul Dano was eventually cast, but Keoghan got the Joker, so technically, it still worked. “I think, subconsciously, when you put something out into the universe and say it into existence, you make choices towards that,” he says. “I don’t believe in God, to be quite honest. I do believe in hard work. If you want to succeed in having that experience, [playing] that part, committing to that energy works.”

Now 31, Keoghan enters a new chapter. He couldn’t play the lost boy anymore, even if he wanted to. And he has a son now, Brando, and fatherhood has reframed everything. “It’s new territory for me,” he says. “It’s definitely making me age quicker. I’ll be able to play the older parts I’ve always wanted to play. When [he] smiles at me, there’s no fucking word I can put on it. It’s beautiful, it’s unconditional, it’s indescribable.”

At the Burberry show, the thing that sets Keoghan apart from the other guests is that he looks happy. Despite unconventional beginnings to a career, he managed to bend it all to his will. Has he been able to pause for reflection?

“Right now, I feel very positive,” he says. “And sometimes feeling positive is unsettling for me. Not to sound really depressing, but [when I’m] in a happy moment, I tend to look for some sort of unhappiness in it. I always tend to think that there’s something else around the corner. Right now, I’m learning to sit in happiness.”

Thank god he found his seat.

Hair Franziska Presche at The Good Company Reps. Photo Assistants Luke Stulinski, Hayleigh Longman, Zillah Rauter. Stylist Assistants Serena Park, Amy Seo, Federico Cantarelli. Tailor Vikkie Tarbuck. Make-up Assistant Aoibhín Killeen. Production Parent. Talent Director Tom Macklin.