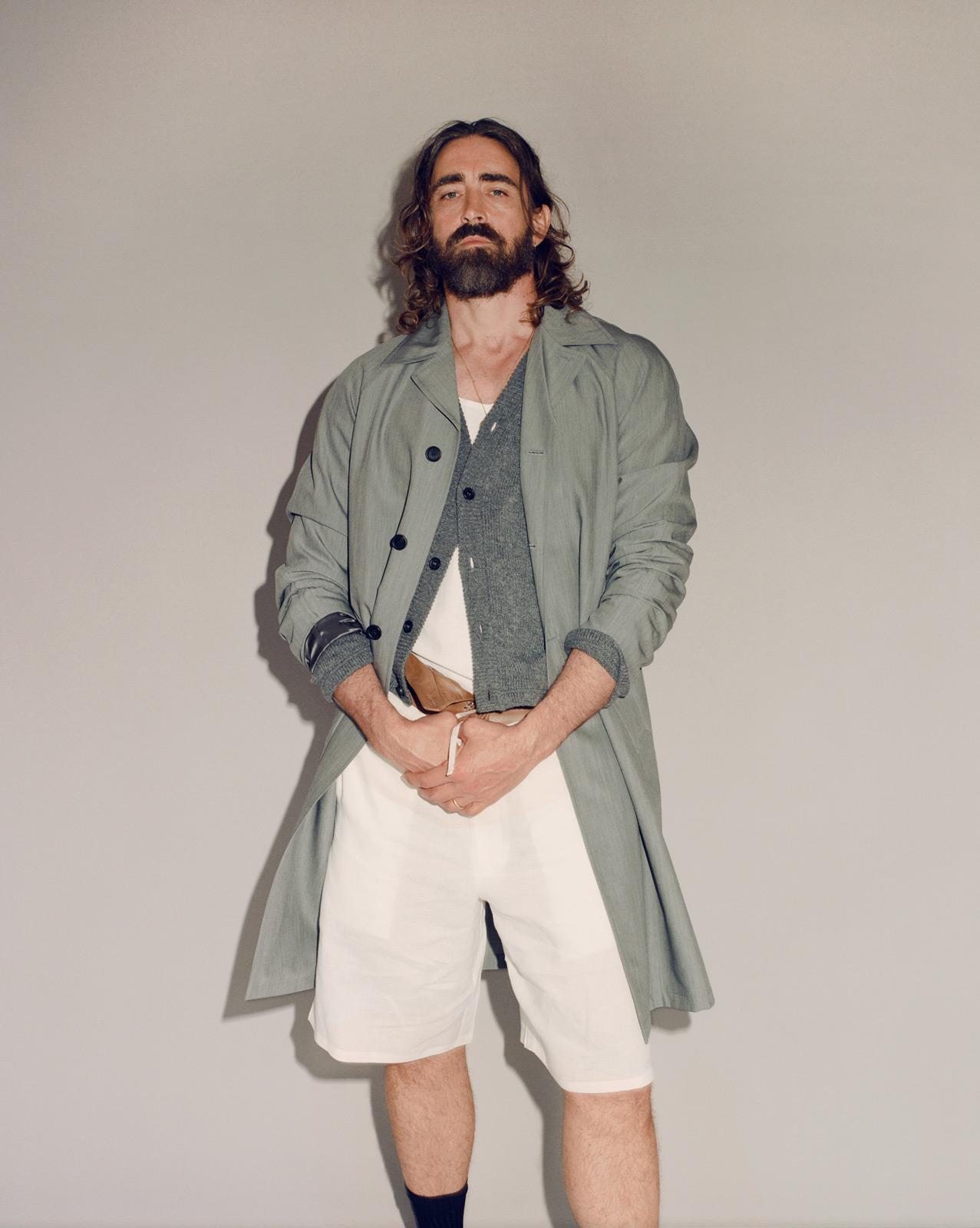

Hollywood’s most versatile actor joins Document to discuss the complexity of the mind, transcending traditional gender roles, and the characters he never forgot

A transgender showgirl. An American soldier with amnesia. A badly injured stuntman. A convicted criminal. An affable outsider, framed for murder. An elven king. A put-upon dog owner. A gay activist. A fast-talking piemaker with a dark secret.

These are just a few of the people Lee Pace has played over the course of his prolific 20-year acting career. After inhabiting so many characters, he says, you realize that some roles can be picked up and set aside at the production’s end—but others stick, even when the house lights are down.

For Pace, one of these characters is Joe MacMillan, the bisexual former IBM executive and aspiring disruptor he played in Halt and Catch Fire: a critically-acclaimed but little-watched drama about the ’80s tech revolution that is, in my opinion, an unsung masterpiece of television. Pace agrees—and when I mention I’m a fan at the beginning of our interview, his eyes light up. “I’m so proud of that show, and I am always happy to hear it means something to someone, because not that many people have seen it,” he enthuses. “I really cared about Joe—he was a bundle of contradictions, a real challenge, a riddle I was trying to solve.”

Pace doesn’t mind carrying characters like Joe around with him—but other roles, he explains, can be impossible to integrate, taking up so much space that they become like “a painful, uncomfortable growth that you need to treat.” “Joe Pitt was one of those characters,” he says, referencing the closeted Mormon lawyer he played in the 2018 Broadway remount of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. “He embodied the experience of being a queer person in a straight world—of having to chip away parts of yourself so that you can navigate it,” Pace recalls. “Playing him onstage every day, night after night, in front of an audience of people, many of whom were queer, and had probably gone through the same thing… Those were painful shoes to walk in.”

It’s a painful show to watch, too. Set in 1980s New York at the height of the AIDs epidemic, the play is a symbolic exploration of homosexuality in America—following Pitt and several other characters who struggle to square their sexuality with their beliefs. “Tony [Kushner] created a character, and then he stripped the skin off that character onstage,” Pace says. “By the end, he is left flayed and shivering—both in deep need of love, and fundamentally unlovable, because there’s this hurdle he needs to clear, and he won’t do it. He needs to be truthful with himself, and he can’t. He loses everything—all the fantasies and relationships that meant so much to him. And the audience is left to wonder, What happens to this man?”

At the time, Pace himself was not public about his sexual identity. Growing up queer in suburban Texas, he learned to rebuff those questions—maintaining privacy as a shield until he came out to his family in high school. Then, he headed to Juilliard, and from there, the silver screen. Though open with those he knew, he preferred to keep his personal life personal, steering interviews back toward his work and away from his sexuality. Then, Sir Ian McKellen—who co-starred with him in The Hobbit, and was among the first openly gay actors to be featured in a major cinematic franchise like Lord of The Rings—accidentally outed him, naming him as one of the queer actors attached to the project in a German-language interview. Though whispers followed, Pace tried to keep things under wraps; in another interview, he recalled having lost agents after disclosing his sexuality. At the time, Hollywood was still skeptical about a gay leading man.

This is all context for why—when Pace found himself embodying this conflict onstage every night—he found it impossible not to see Joe’s problems as his own. “I want to live now. Maybe for the first time ever. And I can be anything. Anything I need to be,” he would say, coming out to an audience of thousands—then, he would go home, and think about what that meant. “I couldn’t just let it go. I thought so much about that character, and what happens to him after the show. For a long time, I thought, You know what Joe did? He moved to Hawaii, met a great guy, and they spent the rest of their life renting surfboards on the beach. He never had to see any of those people ever again. And that got me through for a while,” he says with a faint smile. “But lately I think about him, and I think he was out on the dance floor on Fire Island, sweaty and on drugs and dancing with his brothers. Maybe he got sick, maybe he didn’t. Maybe he found the angel he was looking for.”

Pace is now out and proud; he lives with his husband upstate in a house he built himself, assuming the role of DIY architect, carpenter, and construction worker in between cinematic projects. The effort was mostly informed by YouTube videos, and the fact that he loves working with his hands. Pace started on the house just after wrapping the cult TV series Pushing Daisies, long before he would be seen in Marvel movies and other major franchises, and found that—as his star continued to rise—returning home to work on the land kept him grounded. Iit also instilled in him a sense of discipline, he says, describing it to GQ as “a fundamental lesson [in] self-sufficiency.” He watched countless YouTube videos and learned how to build a timber frame, having hand-designed and carved each joint himself. Then, one day in late November, he recruited a gang of friends to peg it together and lift it up. If Pace had to choose an alternate career, he says, maybe it would be something like that—but at the end of the day, he can’t imagine his life without acting.

What compels Pace toward his craft is simple: the drive to investigate humanity, and offer forth those findings to others. “What I love most about what I do—and I’ve really come to realize this as I get older—is that people have hard lives. They’re looking after the kids, they’re working hard, they’re solving their personal problems. And actors get to meditate on that and study it and interpret it, through their instrument, and then sing the song in a way that’s entertaining—because no one wants to take their medicine,” he says with a laugh. “That, I really do believe, is a worthy service.”

“People have hard lives. They’re looking after the kids, they’re working hard, they’re solving their personal problems. And actors get to meditate on that and study it and interpret it.”

Pace isn’t a method actor per se, but he does dedicate a lot of time toward his roles. “The only way I know how to make sense of things is to think, think, think,” he says, describing how, at the beginning of Halt and Catch Fire, he enlisted his co-stars to do the same, suggesting they all meet every week to discuss their characters. It became a tradition: “We would cook dinner together every Sunday, read the script, and talk about what was on our mind—and in that process, we developed these close relationships in a creative work environment, not unlike the ones we had on the show. We would all defend our characters to one another, and sometimes it would get heated. At the time, I had trouble seeing what it was about Joe that made him so difficult to people. Mackenzie [Davis] would argue that he’s a sociopath—but also, her character was a sociopath!” he exclaims, before sitting back in his chair again, reflective. “We all contain multitudes, don’t we?”

Both Angels and Halt and Catch Fire are period pieces set in the ’80s, with messages that take on a renewed relevance in the modern day: “I think Halt and Catch Fire is the truest representation of entrepreneurship in America—and there’s nothing more American than being an entrepreneur,” says Pace. “You’ve got these people with the right idea at the wrong time—or they have the path perfectly laid in front of them, and they’re the ones who get in their own way. In that sense, it’s also a study of human relationships.”

Angels, meanwhile, explores the human cost of repression, hatred, and sickness. It’s not the first time Pace has tackled these themes: His Broadway debut, The Normal Heart, also focused on the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In that show, Pace assumed the role of gay activist Bruce Niles—one of the countless queer characters he has played over the course of his career, dating back to his breakout role as the transgender showgirl Calpernia Addams in his Sundance-winning cinematic debut, Soldier’s Girl.

This is by design: “I’m endlessly fascinated by depictions of masculinity,” he says. “The kinds of men in the world are as numerous as grains of sand. Yet we are fixated on this two-dimensional notion of masculinity, and a lot of people—especially the characters I play—they’re plagued by it, deformed by it. They spend their lives contorting themselves to fit in, being told they can only be and feel one specific thing, when humanity doesn’t work that way. We’re complex and contradictory beings, regardless of gender.”

In Pace’s view, his recent role as Brother Day in the sci-fi series Foundation acts as an extension of this interest: an embodiment of toxic masculinity, escalated to the point of becoming grotesque. “He’s this man with an absurd ego who believes he has control over nature, over who lives and who dies,” Pace says. “I find his insistence that he is the hero of the story—that he alone can solve the galaxy’s problems—funny, because the only solution he ever proposes is violence.”

Brother Day is the latest in a long line of clones that make up the galaxy’s ruling class—meaning that, in Foundation, Pace has been tasked with breathing life into multiple iterations of his character, the most recent of which is intent on doubling down on his own individuality. (This season, he even has an earring!) “The Brother Day I’m playing now is intent on ending the genetic dynasty, on being the last clone. He resists this notion of imperishable permanence. He is claiming his right to carve his own path—to make his own future,” Pace explains. “Last season, we saw Day have this vision—and what I believe that vision was, is his truth: You’re not a god, you’re just a man. And he’s acting accordingly.”

Themes of free will and determinism loom large in Foundation, which is based on a book series of the same name. “Isaac Asimov began these books not quite as a short story, but as a kind of connected world—it’s all about these characters and the fringes of the galactic empire, discussing their trade routes and whatnot as civilization is falling. And that’s what I find so wonderful about the perspective he takes: It’s this sideways look at the activities of a galactic empire in decline. It’s so sly. It’s so chill. It’s so intellectually stimulating.” he says.

Pace also studies the work of other storytellers. Currently, he’s most invested in Ursula K. Le Guin, and has been moving through her oeuvre with slow, focused intention, saving the books with the most mainstream success—Tales from Earthsea, for instance—for last. He recommends The Matter of Seggri, a social commentary on modern gender roles set in a world in which men have no significance, save for their reproductive purposes. “She has this way of creating this realm of respect and consent in her books, informed by this patient spirituality—and through that, she creates a real sense of space around gender,” he says. “And I’m really fascinated by that. Gender dynamics are extraordinarily complicated; they’re primal on one hand, and extremely civilized on the other. We humans are full of contradictions—and I think the best way we can hope to find enlightenment in that area is plays and books and art.”

When I ask Pace how he feels about watching himself on-screen, he pauses. “If I’m moody and distracted about other things, I’m gonna watch the scene back and be like, Why on earth did they edit it like that? Whereas, if I’m in the mood to have a good time, I’ll have a laugh. And if I’m in the mood to be nostalgic, I’ll remember what happened that day.” He compares the experience of watching his own performance to the way that memories function: your perception of the original event is influenced by the conditions under which you recall it, offering not an objective look at the past, but one filtered through the subjective experiences that make up our lives.“There are times that I watch myself acting, and I understand what I did that day—and then there’s times that I’m like, I don’t see it. I don’t know that guy,” he says with a laugh, then a pause, and finally, an introspective smile: “The mind is such a funny thing, isn’t it?”

Talent Lee Pace. Grooming Amy Komorowski. Stylist Assistant Brodie Reardon. Production Camera Club. Special thanks to Kalle Bergh.