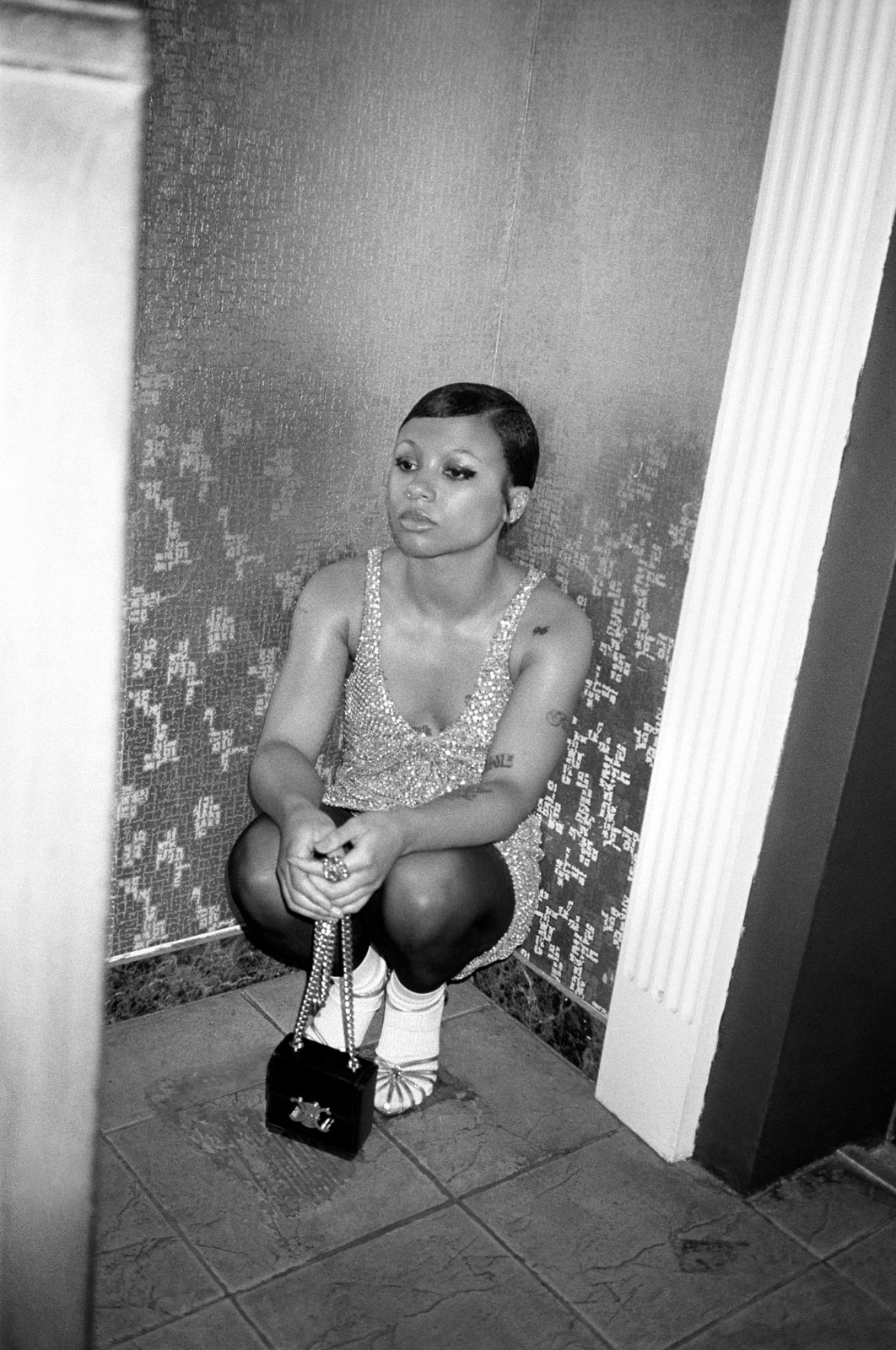

Resistant to the archetype, the actor is emblematic of a new generation of performers, committed to complex characters and storylines

“You’re not going to get me in trouble, because you want me to sing at Mass.” Myha’la Herrold sits at the desk of her hotel room in Wales, with its shitty WiFi and view of the bay, reminiscing on Catholic school. It was a “mutually beneficial relationship,” she says, through which she was afforded an excellent arts education, the scholarship to make it happen, and a free pass to breach dress code. In exchange, the diocese’s optics: brochures and handshakes, the parading around of a very talented Black girl.

“In a lot of ways, especially in an image sense, the school needed me,” Herrold says. “I felt very much like a token.” She took up jazz band and rock band and choir, starring in theater productions both out of passion and in the name of a lifelong game: to study drama at the school of her choice—ultimately, Carnegie Mellon—in the hopes of fulfilling her calling as an actor. She moved from San Jose, to Pittsburgh, settling post-grad in Brooklyn, where she landed her first adult role: Harper Stern of Industry, an HBO drama that follows the personal and professional trials and tribulations of aspiring young traders, as they compete for employment at one of London’s most prestigious investment banks.

Pierpoint & Co. is the “closest thing to a meritocracy there is—and I only ever want to be judged on the strength of my abilities,” Harper deadpans in her opening scene. “And paid for it,” her would-be supervisor, Eric Tao (Ken Leung), quips. There are a thousand layers to Herrold’s taking on of Harper—a tough-to-crack, unpredictable candidate; an American transplant amid a sea of Oxford highfliers; a black-and-white thinker with a Machiavellian streak, concealing the truth that she never actually completed her state school degree. Perhaps most compelling is the actor’s own maturation, alongside her character’s—and the challenges they share in a broader sense, edging into the folds of white-dominated spaces. If the trading floor is Harper’s self-approbation ground zero, Herrold’s was that first day on-set: “It was in a different country. I was entirely alone. I really had no reason to believe that I could do it.”

Needless to say, she managed—“faking it until my confidence became real.” And then Industry blew up, charming viewers with its bleak spectacle of wealth and pseudo-desire and the hamster wheel of success, littered with “all the bells and whistles—sex, drugs, and drama.” People can’t seem to agree on what, exactly, the show is about: addiction in its many forms, capitalism, identity politics infiltrating the boys’ club. To Herrold, Industry hinges on its relationships: “It’s character-driven. It’s relatable, whether or not you understand what we’re talking about—because, honestly, I don’t understand half of [the script’s financial jargon]. The show allows our audience to feel like they’re inside of it, because our characters are deeply, deeply complex.”

The workplace TV drama is nothing new. This American obsession has enjoyed many forms, from the sitcom (The Office, Brooklyn Nine-Nine), to the episodic procedural (Grey’s Anatomy, Law & Order), to the sprawling “prestige” series of the last Golden Age—Mad Men and House of Cards and The Wire. But its freshman class looks different, because our country is different—still seized by the gloss of money and status, but willing to view its pursuit through a darker lens. In Industry, there’s ketamine, and then there’s heroin; hot sex, and sexual harassment; wins that turn out to be losses in an endless Sisyphean chase. “The thing that makes it different from Succession or Billions is that Industry brings its viewers into its world through the eyes of the youngest, least wealthy people,” says Herrold. “I feel like literally anyone can relate to being young and hungry, and going up against your peers.”

“The thing that makes it different from Succession or Billions is that Industry brings its viewers into its world through the eyes of the youngest, least wealthy people. I feel like literally anyone can relate to being young and hungry, and going up against your peers.”

It’s this sort of angle that draws her to a project: fresh characters, with topical stories to tell. Industry prompted Herrold’s inadvertent pivot from the stage to the screen, following a stint pre-high school graduation, touring with The Book of Mormon. “Not to say I don’t love a good revival,” she says, “but, you know, there’s not much of a place for me on Broadway.” In the realm of film and television, the actor held a firmer grip on auditioners’ attention; casting calls were within reach, and far more stimulating: “Particularly with Harper—she was, like, the least conventional Black woman that I had come across [on-screen]. And I never felt like I fit into any kind of box.” It goes back to the burden of tokenization, that Herrold reckoned with as a teen: “Representation is not just all the colors of the rainbow, but [imagining roles] that are allowed to be many, many contradictory things at once. None of it is necessarily pretty. It’s kind of a mess. But everybody loves mess, and everybody can relate to mess. You know what I mean?”

To put it simply, Herrold does the antihero well, all while broadening the scope of who’s allowed to be one. And following Industry’s first season, she joined a whole cast of them. Bodies Bodies Bodies marked one of 2022’s most-anticipated films—an A24 black comedy horror, directed by Halina Reijn, with the cool-kid cast to end them all. The plot goes something like: A handful of rich, anxious, perpetually online twentysomethings make the trip to a friend’s mansion when a late-night hurricane cuts the power. They’re picked off by an untold murderer. It’s an ironic, (knowingly) done-to-death commentary on the worst parts of Gen Z culture, featuring youthful nihilism of the much less lucrative variety, sat next to the crew at Pierpoint.

As Industry does with the workplace drama, Bodies Bodies Bodies toys with the slasher. We know these tropes well: On an anniversary or holiday or some other significant night, a killer (usually a man, usually wielding a knife) tracks down and murders a group of victims, one by one. Characters of note are the “first to die” and the “final girl”—political choices in the horror landscape, perhaps more so than the identity of the villain himself. Reijn takes care to lay out such a sequence, subverting expectations little by little (the white guys perish first, the murderer has no clear MO), working up to a critical point: There is no killer—or, each and every character comprises his whole.

Herrold plays Jordan, the antagonist stood between Sophie (Amandla Stenberg) and Bee (Maria Bakalova)—a six-week-old couple, characterized by the former’s love bombing and the latter’s general meekness. These three are the last left standing, with Jordan’s being the conclusive death. From start to finish, she teases out the lack of trust within the group—alleging a recent affair with Sophie, compelling Bee to Check… her… texts with a dying breath.

As much as Bodies Bodies Bodies presents a character list of modern-day archetypes—vapid podcaster (Rachel Sennott), silver-spoon-fed cokehead (Pete Davidson), middle-aged himbo you met online (Lee Pace)—it’s Herrold’s performance, in particular, that leaves you wanting for a prequel. There’s a bitchy-just-because to artfully manipulative to cripplingly neurotic arc to Jordan, all conveyed through a thick mist of apathy. She scoffs at her peers’ symptomatic insecurities, then catastrophically fails to combat her own, resorting to the same violent paranoia actively bringing about their collective demise.

Parallels could be drawn between Harper and Jordan: pragmatic, impassive, brave characters, whose complexities flood in when masks are lifted, in scenes few and far between. “But as a human being,” Herrold says, “I’m nothing like those people.” These roles, her first major credits, are far from representative of her breadth as an actor, just beginning to come to light. “I want people to say, She has that range. I’m very much ready to play something more innocent, something in the world of romance—a character who’s not so on-the-outside.” Returning to live performance isn’t off the table, nor is bringing her voice back to the forefront. Her dream role? Eartha Kitt in a biopic: “I haven’t sung in ages—and I love her with a passion.”

“Everybody loves mess, and everybody can relate to mess. You know what I mean?”

In the works are two film projects: There’s Dumb Money, Craig Gillespie’s biographical dramedy on the GameStop short squeeze of 2021. “I’m excited to see that one,” says Herrold, “because there’s a bunch of separate storylines. I was really only with Talia Ryder for the 10 or so days we shot. It’ll kind of be like seeing a movie I’m not in.” Leave the World Behind is a psychological thriller, adapted from Rumaan Alam’s novel of the same name; in the face of a cyberattack, two families—one white, one Black, both well-off—are forced together inside a Long Island vacation home, grappling with survival side-by-side. Kevin Bacon, Ethan Hawke, and Mahershela Ali assume starring roles (“I’m really hoping that I’ve held my own against the big dogs”)—but Herrold seems most staggered in the face of Julia Roberts: “I was very much just taking notes. I want people to look at me the way they look at her.”

It’s clear that Herrold pays respect to the greats of her industry, and all the way down from there. The only child of a single mother, that virtue’s been instilled as her cardinal rule: “[I was taught], You do whatever you want to do—but karma exists. Respect applies to everyone and everything.”

So she navigates acting as she navigates life: with give-and-take in mind. Herrold’s profession, “collaborative by nature,” no longer makes room for scene-stealers. Her unfolding oeuvre carves out distinct paths, for more open-handed stars—smarter, younger, relationally minded, quicker on their feet. They seek out new perspectives or live them as people, with the knowledge of one intrinsic truth: “You won’t gain the most success unless everyone’s allowed to do what they do well.”

Hair Bob Recine at The Wall Group. Make-up Yadim at Art Partner. Manicure Eri Handa at Home Agency. Photo Assistants Zane Shaffer, Matchull Summers. Digital Technician Sebastiano Arpaia. Stylist Assistants Oré Zaccheus, Malka Krijestorac, Rachel Le. Hair Assistant Le’Kema Allman. Make-up Assistant Aimi Osada. Production Block Productions. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan. Talent Director Tom Macklin. Post Production INK.

Document Journal Spring/Summer 2023 Issue No. 22 is available for pre-order now. New covers will be unveiled over the coming days.