In 'Farming,' Idris plays a teenage Akinnuoye-Agbaje as he seeks empowerment through joining his neighborhood skinhead gang

This conversation will appear in Document’s upcoming Fall/Winter 2019 issue, available for pre-order now.

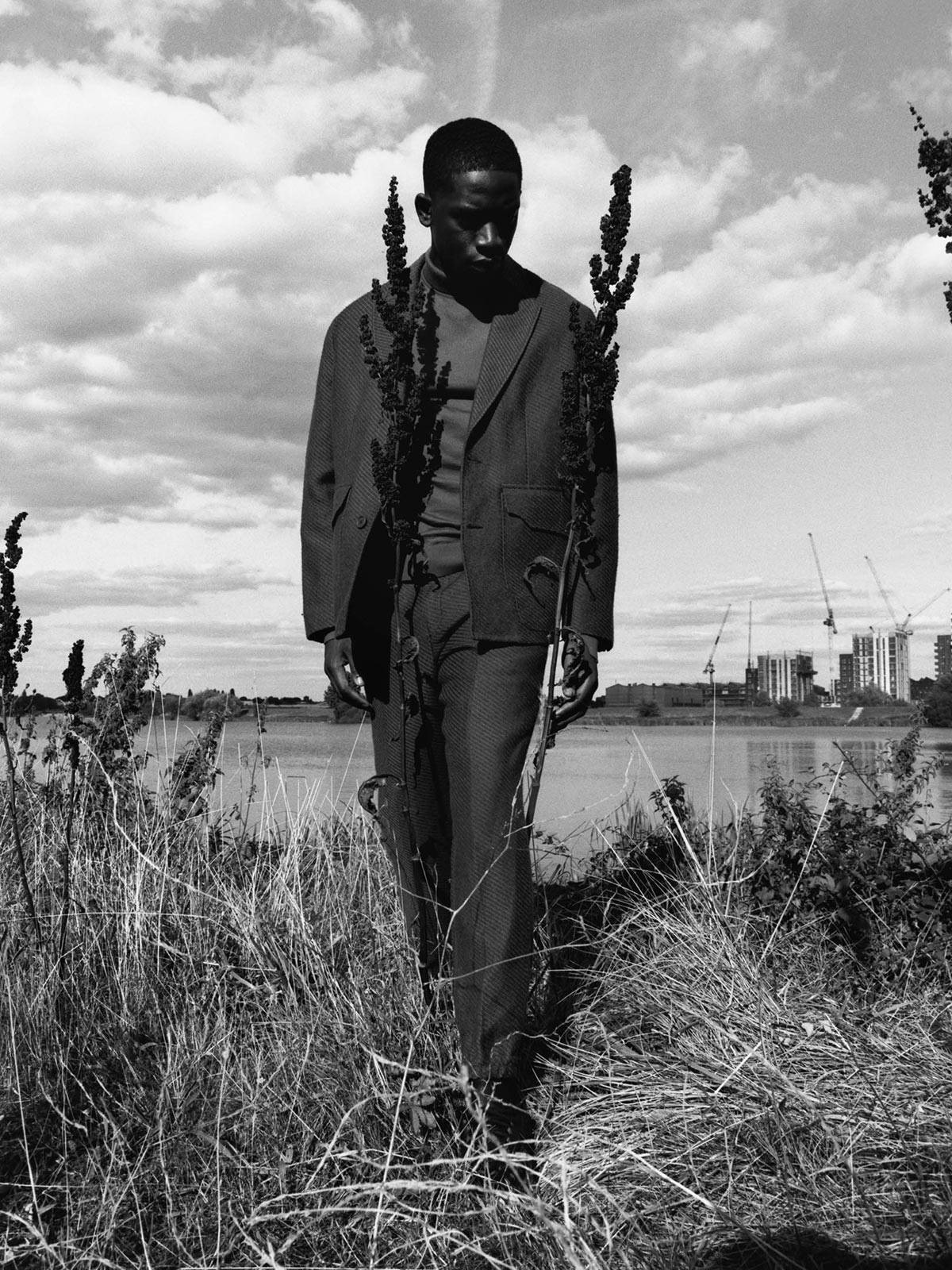

In Harper Lee’s seminal novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, lawyer Atticus Finch tells his daughter Scout: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view…until you climb in his skin and walk around in it.” Actor Damson Idris understands this plenty, given that he lives in other peoples’ skins for a living. But in his latest film, Farming, he is tasked with doing so in an unusually intense way: interpreting the life and experiences of his director.

Farming is the extraordinary story of a British Nigerian teenager called Enitan—played by Idris—who joins a white nationalist skinhead gang. It is also based on director Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje’s real life story. The title refers to a widespread but little known phenomenon where Nigerian immigrants would ‘farm’ their children out, often temporarily while they worked or studied, to predominantly white British families. Akinnuoye-Agbaje was fostered by a white family in a working class town, Tilbury, in the 1970s, at the time a breeding ground for white nationalism and violent extremism.

The film, which premiered at Toronto Film Festival last year and released this Fall, explores the febrile climate of the time, that leads Enitan, after years of racial abuse, to align himself with his white oppressors. And while it may be set in 1970s England, Farming deals in concerns that remain pressing from male violence and racism, to the crisis in masculine identity, a subject Idris is also exploring through his collaboration with Ermenegildo Zegna’s #WhatMakesAMan campaign.

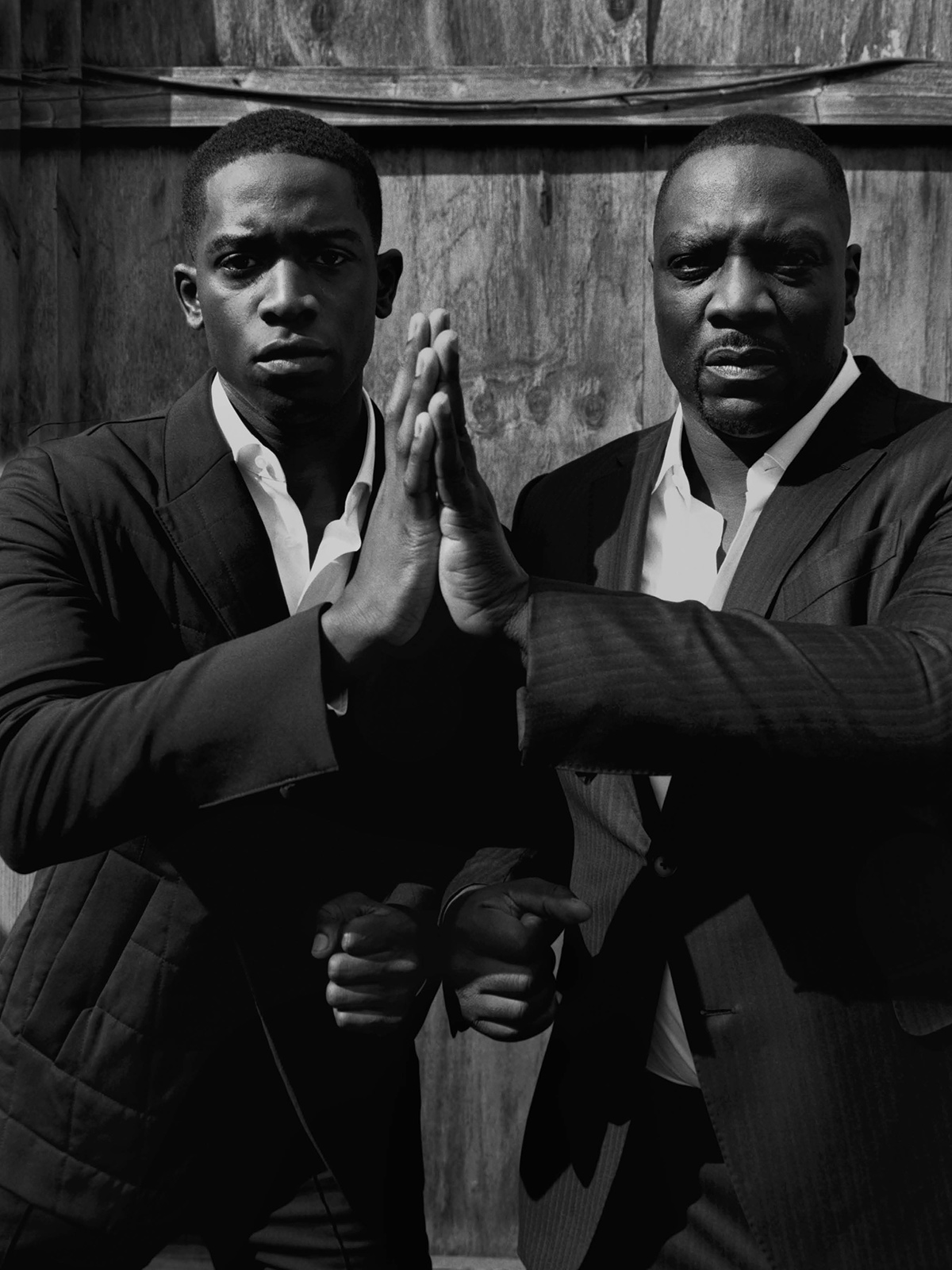

As a result, the work led Idris and his actor-turned-director Akinnuoye-Agbaje, who has worked in front of camera in shows from Lost to Game of Thrones, to some pretty dark places together. “It is very personal, intimate, sacred space and experience with you,” says Akinnuoye-Agbaje, 52, when Document meets with the two men in London in September. “When it needed to be turned on those experiences were the things we used to access, and it was totally between us, to keep it sacred so it wasn’t abused.” Idris, 28, who broke out in the FX show Snowfall agrees: “And only we knew, no one else knew. That was our special thing that bonded us.”

This bond is apparent when the two men, who spend increasingly less of their time in their home city London (they hadn’t seen each other in a year), meet for tea in The Standard hotel. Immediately warm and brotherly, their conversation is always easy and fluid, even if the topics are often not.

“A lot of the youth today, especially young men, are mixed up in badness, are involved in knife crimes, because they’re trying to find a sense of belonging in gang culture. But if you could just know yourself, then you can accomplish anything.”

Damson—This film speaks to identity. The whole movie is about adolescence. My character has been taught self-hate and is trying to find his identity. I relate to that; teenagers relate to that. A lot of the youth today, especially young men, are mixed up in badness, are involved in knife crimes, because they’re trying to find a sense of belonging in gang culture. But if you could just know yourself, then you can accomplish anything. You, Adewale, sitting right here, proves it.

Adewale—Even though the story occurred over 30 years ago, the themes are still relevant. You know, identity, belonging, acceptance, racism…

Damson—Motherhood…

Adewale—Ostracism. Being an outsider, gang violence. It’s a case study of how young adolescents can end up in life- threatening gang culture. That’s why, when I was looking for someone to play a younger version of myself, the lead character in the movie, I wanted somebody who wasn’t polished. I wanted a rawness that I could harness. I remember when we first met. I’d heard whispers of an emerging black British talent.

Damson—I mean, of course. I’m fantastic!

Adewale—[Laughs] You did that audition at my apartment in L.A. and it was outstanding. Many of the very accomplished actors that we were seeing tended to gravitate to the more violent nature of the character, and what was required was an innate sensitivity and decency so that you could root for him regardless of what he was going through. You can’t really act that because the character doesn’t say more than 10 words throughout the whole movie. He’s emotive. So, it’s really important to have that sensitivity and you could do that flawlessly.

Damson—I told you I’m a big deal [laughs]. That meeting was so important for me because I could picture the guy, but I really just wanted to get in front of you and see what you had in your mind about this kid. We had those conversations when we were rehearsing in London and we’d sit down and just talk for hours about stories and circumstances that he was in. That’s now influenced how I approach every single role. I need to know the stuff that’s happened to this person off the page because that influences everything! Like that situation you had with the police in real life that isn’t in the script, remember you told me about that?

Adewale—I remember it very clearly. I was six and going to primary school. It was autumn and the sun was out, there were leaves on the ground. All the kids were walking to school and there were two police officers in a car opposite. One of them beckoned me over. He smiled, spat in my face, called me a n****r and drove off. I just remember looking at the sun. That hadn’t changed. The leaves were still there, people were still going to school, and I just remember the heat and the hot saliva going down my face and not understanding what happened. But I just had to wipe it off and carry on to school. In the movie, that experience informs the skinheads’ standoff with police. Eni is seduced by the power the skinheads have against the police, who oppressed him. He says to himself, I want that power. That’s a reason he was seduced into that skinhead gang because of the fearlessness that they showed in front of the police. We took you to Tilbury as well, where I grew up and the real story happened…

Damson—I wanted to know exactly where these characters came from. The funny thing about Tilbury now is that it’s flipped and there’s loads of Nigerians.

Adewale—There’s an irony to it, you know, because my siblings and I, and other foster children, were the first black children entering that part of England. As a consequence, we faced a lot of racial persecution. And then, when we went back for the film, at least 60% of the population is black, and 90% of those are Nigerian. There was one pub that is shown in the movie called the Anchor Pub, and growing up, it was a house of fear for me, because if you walked by it and you were an ethnic minority, you would most certainly be set upon. It was a right-wing kind of pub where skinheads, sailors, and dockers congregated. It was known to be violent. That pub is now a Nigerian church.

Damson—Karma’s a bitch [laughs].

Adewale—Life is very mystical, and perhaps that is why we ended up landing there in the first place, but who knows.

Damson—We met this African guy in Tilbury who told us when he arrived there 20 years ago the locals threw eggs at him. The film was educational for me. A year after I finished it, I discovered that my sister had been farmed in the same way as my character in the film. She was sent to live with a white family for a whole year after coming from Nigeria. My mum was selling goods from London to Nigeria so she had to go back there. She was also studying, working a million jobs. This story shows a piece of British history that hasn’t been discussed. Before the film, I didn’t know anything about farming.

Adewale—That’s what is fascinating. The farmed children essentially became a part of the first black British generation to be born on British soil. And then the subsequent generation didn’t seem to have any knowledge of the phenomenon. That’s why it was important for us to journey back. It’s important to acknowledge the impact of racism. There is a distinct correlation between racism and self-hatred. And that is a very real psychological condition that affects generations long into their adult lives.

Colin Crummy—Why are violent nationalist and racist movements so male orientated?

Adewale—It was a violent culture that we lived in. Violence was a dialogue, a language that we spoke.

Damson—I remember we were doing a scene and you wanted our interaction around ‘hello’ to be violent, like, Hey, what’s up? Boom! Head butt, punch in the face, you know, smack on the head or whatever. That alone, if that’s how you say hello…

Adewale—That was the language—you head butt each other as a greeting. But why men? Why was it like that? It’s the lowest expression of human character. Our natural expression is compassion…togetherness. No man is an island, we want to be together. You look at the sun when it’s out. Everybody’s in the park. Even though you’re not talking, you like the company of others so that’s our natural tendency as human beings. Our lowest is violence. It’s a primal instinct, a lowlife condition. Violence is going to be prevalent in areas, where, for instance, there’s poverty and there’s no education to enlighten you about other tools of expression. It’s both men and women, but because males are the more dominant physically, that’s where it comes out. It also comes from low self esteem; an insecurity that means you should feel that you should embrace these packs. As we’ve seen in the film, when your character finds somebody that believes in him, and he’s provided with an opportunity by his parents, there is a transition.

Damson—And that’s the first opportunity.

Adewale—Right, yeah. If you ask why young men today are stabbing each other on the street, you have to start with the nurturing. Who’s policing them at home? And what’s the opportunity that they’re exposed to? You yourself fought hard to get out of a certain mindset. You got into football. Then acting. If you don’t have those opportunities to take you out of that mindset, you get tunneled into those negative situations.

Damson—When I was 16, there was always a football pitch or something on the corner to play with. Now kids just stay in their house and play games. One of the huge negatives about gentrification is you don’t know your neighbors anymore. Even though there were 50 to 100 boys my age in my area, I knew every single one of them. That’s Jason, that’s his mum. That’s Peter, that’s Tyrese’s little brother. I mean, now, they have no idea who’s who. So they’re going to war with people who live above them.

Adewale—I agree. I think there’s been a prostitution of our values. Materialism now defines kids in society, rather than an appreciation of who you are as a person. Like you said, knowing your neighbor, knowing your mate. It’s all become about material acquisition as an identity. And that’s the constitution of our culture. Values really are what make Britain great. We’re very traditional. And when those traditions are sabotaged, that’s when society starts to fall apart. The other point about the film is that it’s about people who are searching for belonging. It’s a male-dominated film, but the story is very much driven by the search for mothers.

Damson—It’s interesting that the lead skinhead, who is also the eldest, is looked upon as a father figure. That makes them easily manipulated. The lead is very smart and intelligent, compared to the rest of them. When I was younger, something really bad was going to happen to me and a gang leader saved my life. I was talking to him recently and he didn’t even remember the incident. He was like, ‘When did that happen?’ This shaped so much of my life. I wanted to pursue football, I went to college, I went to university, I became an actor, just so I could get out of being in those types of situations, and he doesn’t even remember. I’m sure, if Enitan went back to Tilbury, people probably won’t remember.

Adewale—Well, actually I did go back. I interviewed one of the skinheads who was a rival. He remembered a lot of stuff. He acutely remembered who I was. He was in the rival gang. When we got out of school, we’d fight each other. I wasn’t sure how it was going to go this time. I was quite nervous, because I wasn’t sure if he’d turn up. But he did. It was one of the most profound experiences.

Damson—How is he now?

Adewale—He’s working with young offenders. So he’s doing a brilliant job, doing some proactive work with the youngsters, so they don’t end up back in prison. When we finished recording the documentary, he came up to me and said, ‘I’m really sorry.’

Damson—Aw, I knew it! That’s the stuff.

Adewale—He said, ‘I didn’t know that’s how it made you feel, and I’m really sorry about that.’ I know the world from which he came, so an apology like that…it means a lot. If doing this film would produce just that conversation, it was worth it. Because he grew, I grew, we grew, we got complete with each other. He’s doing great work in his life, and we realized we had more in common than not. He talked about his family background and how disenfranchised it was, the lack of a father figure in his life. We connected on a human level, which enabled him to just say, ‘I’m really sorry about that. I’ve changed.’ And he meant it. So that was a big deal for me.

Damson—The most important thing about this movie is that love was key to my character’s triumph. It wasn’t more violence, it was love. If more young people had role models they can look up to, they would be able to walk down different paths. If I didn’t have my two older sisters and three older brothers, then who knows what path I would’ve taken. It’s very important for parents to come up and others to set the standard and be like, There’s a bigger reality than carrying a knife, or trying to seek instant gratification. You can accomplish anything in life, all you’ve got to do is get your head down and work at it.

Adewale—You nailed it. It’s all about love and caring, it starts from there. That’s what we need more in society. Maybe it comes from the home, or your friends, or a mentor. What we’re doing today has consequences for how we’re going to have to live tomorrow. So if you want to know what the future is going to look like, look at how we’re treating our children. The hope is with young men like you, with that kind of attitude. That’s our future. The more young men that are exposing themselves to different experiences, learning. It’s only going to help. Because they will be the decision makers in another 10 to 20 years. We’ll be pensioners or gone.

Damson—I’ll still be out here in these streets!

Adewale—You’re the ones. We have to impart hope to you because you’re going to carry the torch.

#WhatMakesAMan, Ermenegildo Zegna’s new Fall/Winter 2019 campaign, confronts the future of masculinity by seeking to eliminate negative stereotypes and embrace love and self-expression.