"Blackness and queerness are just such expansive and deep wells of knowledge and inspiration. It’s a gift to be able to access that and create work that is formed by this abundance."

As June disappears in our rearview—rainbow flags removed from their poles, colorful corporate imagery assuming its normal aesthetic, and glitter washed from Greenwich Village cobblestones—the city will inevitably lose awareness of the landmark riot that began it all. The Brooklyn Museum is prolonging the remembrance with an exhibition memorializing Stonewall and the 50 year anniversary it celebrated this past June. Nobody Promised You Tomorrow—titled with the words of transgender artist, activist, and Stonewall icon Marsha P. Johnson—compiles works from twenty-eight LGBTQ+ artists across many intersections and identities to bring together one common feeling—Pride. The exhibition, which is taking place until December 8, weaves together mediums of painting, installation, performance, video, and sculpture to memorialize the fateful event that changed the course of history.

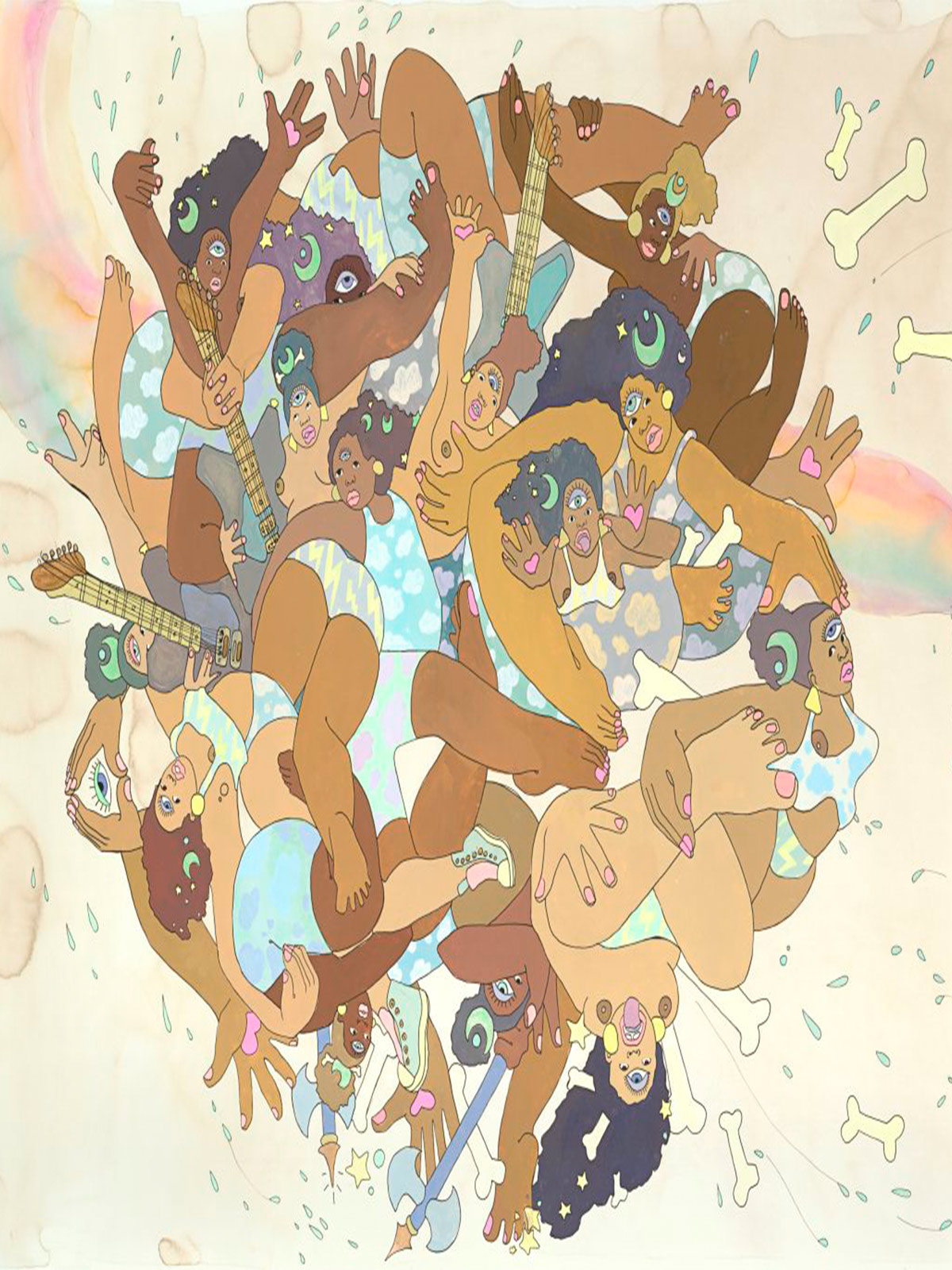

Document spoke with two participating artists, who find themselves right in the intersections Johnson and other LGBTQ+ activists often exist within. Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski is a queer, Afro-Puerto Rican multidisciplinary artist, who practices her craft with a dash of magic and lots of femme imagery, currently pursuing her MFA at the Yale School of Art. Her counterpart, Kiyan Williams, is a gender non-conforming multidisciplinary artist who roots their art within diasporic histories, often utilizing sediment and debris as tools for metaphor. Both artists sat down to unearth what it means to be an artist navigating through identities and how to keep your head above water in the sea of culturally imposed categories.

Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski—Kiyan and I have this really awesome history the past two years of randomly passing paths. So I’m really excited, Kiyan, to get to chat.

Kiyan Williams—Likewise!

Sophia Segarra—So, to begin, if you could talk a bit about your involvement in the show Nobody Promised You Tomorrow and what it means to you?

Amaryllis—I really love this show. I feel really excited about the work that everyone is doing. It’s unlike any group art collaboration that I’ve been able to participate in, in the sense that while it is in the Brooklyn Museum, it really feels like a show that is based in community. It also feels like it has a strong femme center, which I’ve never seen or been apart of in a large group like this. It feels so necessary for femme and queer femme to see a dynamic understanding of multiple perspectives, and it feels like that is present. I wonder what your experience has been Kiyan, but I see so much of my community there—it feels wild.

Kiyan—It’s also been a very wonderful, exciting, and transformative experience being in the show. I had just started my first year of my MFA program at Columbia, and I was particularly disappointed by the kind of people who were engaging with my practice. Mostly the heterosexual, straight, white people were coming to my studio and offering me feedback. I wasn’t having many conversations around queerness or blackness. I felt there was a kind of conversation I wasn’t having—that I wanted to have. So, I just did a cold call email to some curators who’s curatorial projects I found really engaging and really exciting, and who were doing works with race, gender, and queerness. Curators of the exhibition came to the studio in Harlem, and I showed them several different projects I was working on. I got an email maybe a couple months later, asking me if I would be interested in presenting my project Reflections in the exhibition that they were curating. At that point in a journey, as an artist, it was really affirming to have a need that I felt wasn’t being met by the institution I was in and taking an initiative to reach out to the people I wanted seeing my work and engaging in my practice.

Amaryllis—I love that too, Kiyan, because oftentimes being a working artist felt just totally closed in mystery. So I love you sharing that background of what that process was to you. It also is very empowering to hear that there was an absence you took that risk to fill, for yourself; I think that’s awesome.

Sophia—Can you also each speak about specifically how you got started in making art and what made you passionate?

Amaryllis—I can look back and see that it’s always been a part of who I am. I grew up moving around so much that reading and drawing were anchors for my life. My process of becoming an artist and claiming that feels really similar to my coming out process—I had to understand who I was first and be able to accept that. I had this inherited shame around what it meant to be an artist. It’s also just a part of who I am in the sense that I can’t imagine doing anything else. At a certain point I started practicing saying ‘I’m an artist’ It felt really embarrassing, to be honest. It brought up all the shame that I had around why I got to say that. And then it was no question. It is who I am. It is the work that I do. It is what I feel like I bring to the table in terms of what I have to offer. I would say that process wasn’t something that worked right away. I really fought to be who I am, an artist, to know that regardless of external validation by experience.

Kiyan—I empathize with having a deep sense of internalized shame about becoming an artist. Because I am from a working-class family, I‘ve always known I have to do something with my life that will ultimately help me sustain my livelihood financially. I didn’t know how art-making could do that as a profession. In undergrad, I studied a mix of African American Studies, Women and Gender Studies, Queer Studies, and also took studio art classes. So, I was just experimenting with asking these questions about history in relationship to blackness and queerness, while also experimenting with different forms of artistic expression. Art-making is a form of making that allows me to engage in history and think about questions of embodiment when it comes to identity. I realized that I could do all the things I always wanted to do by being an artist.

Sophia—So, as you both are members of the LGBTQ+ community and you both are people of color, do you believe there is a responsibility to make art, or do you think it should come out naturally—do you have outside pressures?

Amaryllis—It’s important for me to understand that the art has always been oversaturated with identity. When it becomes frustrating is when it centralizes identities that are so pervasive that they become forces that operate invisibly. I think that as different artists who have been marginalized within the world, there’s a conversation around the resurgence of identity politics, and for me it’s the way to flatten the breadth of what we are bringing to the table as artists.

Kiyan—Yeah, that also totally resonates with me. The very unique lens which I experience the world is a gift. Blackness and queerness are just such expansive and deep wells of knowledge and inspiration. It’s a gift to be able to access that and create work that is formed by this abundance. I also think sometimes work about identity within a hegemonic context often translates to making work about identity that is easily packaged and legible to the dominant gaze. But as an artist, I get to make work that is super complicated and nuanced, mining that well of blackness and queerness.

Sophia—As your prominence grows, how has it been handling and interacting with both big institutions like the Brooklyn Museum and the wider audiences they bring?

Kiyan—For me, it’s been great working with the Brooklyn Museum. It’s been such a seamless process and support has been really generous. There’s also been great visibility. My project Reflections is based off of an archival video from an artist called Marlon Briggs. I’ve been doing research in his archives, and I encountered an interview he conducted with a black, trans, feminine, gender non-conforming artist Jessie Harris. The project is really just running to give voice to the experiences of this artist Jessie Harris—who speaks very candidly about what it means to be black and gender non-conforming in the 80s. The project was to assume the voice of the artist, and let Jessie kind of speak the experiences on their own terms.

Amaryllis—I have to second what you were saying about working with the Brooklyn Museum. I have loved working with the team. I also love knowing that there’s lots of different people who are seeing the work, from lots of different experiences and perspectives. That is something that I always dream of—when I dream of my work being seen in the world. A couple years ago I had this video piece, and I remember reading one comment that was “what has the world come to” and it was just so delicious, because I feel that way so often in the world, what is going on? what are we doing? I love that art can do that in a way that I think can be present and flamboyant and celebratory and also destabilizing at the same time.

Sophia—What excites you about making art today, are there any artists you’re excited by?

Kiyan—Being an artist gives me a platform and a process through which I can witness and process the experiences of living in these times and create a discourse around it that’s formed by my own particular lens of being a human. Sometimes I forget how much of a privilege it is to be an artist, even though its extremely challenging—every day I wake up and I get to explore and reflect on the things that haunt me, inspire me, and I get to render them tangible and share them with other people, and that feels like a gift. It’s something that I’m really grateful for.

Amaryllis—Yeah, I really resonate with that, Kiyan, what you were just saying. In my life I have often had the experience of the addiction to categorize. It’s just the way people feel faith, like they know their ground is stable. But I really feel excited about my work as an artist being an ongoing practice tending to the in-between. I feel inspired by the audacity of artists to make art. Kiyan, what you were saying really resonated with me about it both being an intense challenge and a wild privilege. There’s so many artists, both past and living—Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Belkis Ayon, Saya Woolfalk, Azza El Siddique, Genesis Baez, Chitra Ganesh, how about you Kiyan? There’s so many.

Kiyan—Beverly Buchanan, Rafa Esparza, Patrisse Cullors, Miatta Kawinzi, so many others whose work, I think, is really rigorous.