Amidst the loud landscape of grail pieces and hyper-consumerism, the most subversive trend is turning your back on it all.

A few weeks ago, a friend showed me a video of a group of teens, occupying a narrow alley somewhere in Greece. One by one, they stepped into the center of the circle they had formed and looked into a camera. It wasn’t the cypher I thought it was going to be. Instead, a boy stepped forward and started showing off each article of clothing he was wearing: Calvin Klein jacket: $200. Armani jeans: $300. Nike x Off-White shoes: $400. And in his final trick, he pushed up his jacket sleeve to reveal a Hublot watch: $15,000. The grand total was $15,909. An impressive near $16,000 performance that lasted only about a minute, and he did it all with his airpods still in.

The video was produced by The Unknown Vlogs, a YouTuber who hosts a series called “How Much Is Your Outfit?” where the host travels around various countries asking young hypebeasts to namedrop the labels they’re sporting along with the prices of each garment. Each item is underscored by a cha-ching sound effect and once the individual is done pimping their outfit and calculating the total (which typically lands anywhere between five to seven figures) said hypebeast will usually throw up a quasi gang sign before cooly swishing their Bieber bang to the side and flashing a smug grin into the camera.

After watching that video, I couldn’t help but reflect on how this attitude towards clothing mirrors a larger cultural mindset. On a global scale, the accelerated pace of information output has fed our mindless cultural addiction for more. This obsession manifests beyond an acquirement of the latest Apple product or knowledge of the buzziest events; it has spread into the very DNA of the fashion market. Near-hour long fashion shows and the premise of only four collections a year are only nostalgic whispers of the past, replaced with near ten-minute blips of models and fabric, pop-ups, surprise drops, and terms I still don’t understand, like “Instagram Fashion” and “pre-fall collections” (doesn’t this just mean summer?) With such a focus on quantity, fashion becomes less about self-expression and more about announcing to your Instagram followers that you’ve acquired the latest Nike drop.

Everyone should feel empowered to flex however they wish with whatever means they have, but watching those teens rattle off brands made me consider the origins of streetwear: born out of late 1970s LA surf and skate culture with Shawn Stussy, founder of the first-ever streetwear brand Stussy, at its forefront. The brand was embraced by a diverse confluence of hip hop, punk, and metal subcultures that formed the heart of American street culture in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The subversive, DIY aesthetics they pioneered gave a validating voice to marginalized communities as well as to lifestyles on the outskirts of the mainstream. For hip hop heads in New York in the 1980s, it was a competition of who could not only outperform the other but out-dress. Streetwear godfather Dapper Dan epitomized the essence of subversion by taking fabrics from luxury brands and reconstructing them to make his own designs. He reimagined the inaccessible and made it accessible—and cool—with iconic tracksuits, coats, and puffy-shouldered bombers for his community, who went to him to find something they could wear to assert their own audacious style and power on the street. Brands like Cross Colors, created in 1989 as the first hip hop clothing brand, Champion, Reebok, Rocawear, Nike, and Adidas (which became largely embraced by the hip hop community and gave rise to sneaker culture) marked a time where fashion was a vehicle to tell people what you were about or, at the very least, what you were striving for.

In comparing the roots of streetwear with the observation on today’s vapid attraction for more in fashion, it’s worth considering that perhaps we have gone overboard to the point where our collective focus has shifted from creative expression to mere logo-pimping. In the consumer’s accelerated zeal for label-driven clout and, consequently, fashion’s zeal to please their consumers, we risk losing our inherent sense of taste and expression unique to the individual. We risk reducing what we’re able to say through clothing and why we’re wearing it to the information listed on the tag.

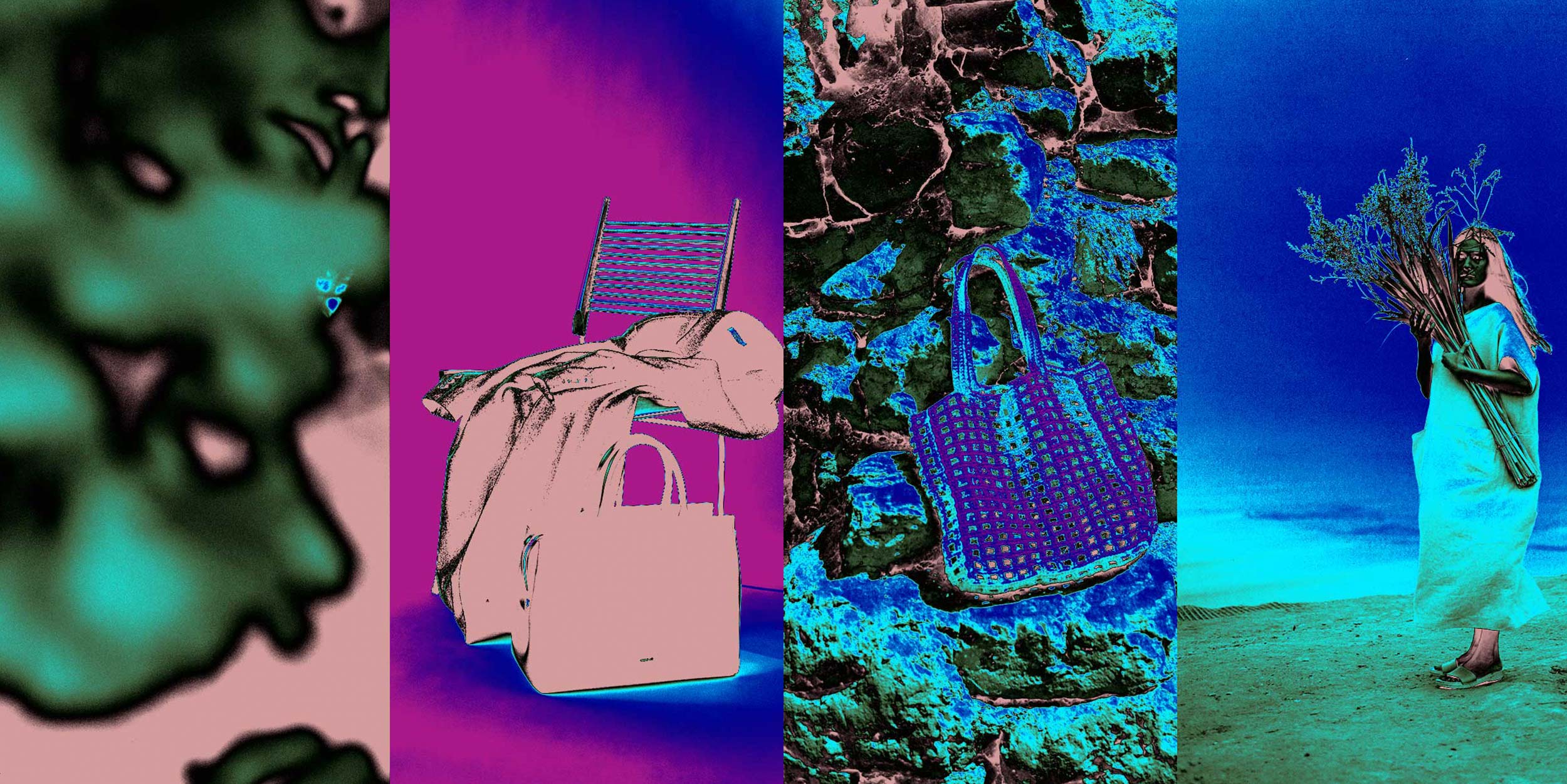

While this is the wave fashion has been riding over the past decade, there is also a growing movement signaling a promising shift in tide, reinvigorating the thrill of being able to both express and find yourself through clothing. Much like the way Millennials and Gen Zers are openly embracing self-care in their content-inundated lives, young fashion designers are also forging a beautiful reprieve from the rat race of trends by focusing not only on the quality of construction but also on the relationship between the garment and its wearer. Iconic minimalist fashion labels such as Issey Miyake, Jil Sander, and Helmut Lang have been cultivating the deeper personal resonance to be experienced with clothing through impressive yet quiet designs for decades. Today’s generation of minimalist designers is continuing this narrative through a unifying premise of fashion that is quieter, fashion that is more intimate, and fashion that strives to allow the wearer to feel a little bit more like themselves by directing the focus on the inner self over the broadcast self we project on screens.

“There are so many brands making hundreds of garments per season because there is a rapid hunger of consumption that needs to be satiated in our era of instant gratification,” says Jake Matluck, creative director of up-and-coming minimalist brand The Solipsist. “I want to combat that and present a new model of consumption and ethos around what we bring into our lives and how that, in turn, impacts our quality of life.

“‘The Self’ is a major facet of The Solipsist. Solipsism is generally regarded as a narcissistic, nihilistic outward view on the world; however, I personally interpret it less so as we are alone in the world and more so as a self-reflection. If we can only be sure of our self and inner thoughts then the things we bring into our lives should have meaning and be carefully considered.”

Confidence, comfort, and being able to find yourself in what you’re wearing are all qualities of fashion that are ultimately invaluable and establish a deeper connection with clothing as opposed to quick flings with fleeting trends. It causes its wearer to slow down and fully immerse themselves in it, an effect that designer Lauren Manoogian strives for with her eponymous label which focuses on what Manoogian calls the “subtle essentialism” of design. “The collection is more about a tactile experience you as the wearer are having, your mood or emotions, and not about outward signifiers designed for other people to recognize—which itself is a statement. The act of wearing clothing is sensory, and there are experiential elements reserved exclusively for the wearer themselves.

“I work to remove unnecessary elements from the design to get to the point of each piece and what it wants to be. Each juncture and detail of the garment and accessory is considered. This may not be immediately evident to those using or seeing the piece, but perhaps over time they notice the unconventional or unique subtleties, or maybe they never notice at all but intuitively are attracted to those quiet qualities again and again.”

This attraction to quietude emphasizes the healing properties embedded into anti-trend fashion. For a hypebeast, a flex is a several thousand dollar hoodie decked out in script and graphic overlays which boosts them with the confidence to walk taller in their Yeezys. But, a flex can also be felt in something aesthetically more simple.

“My wearer is strong, confident, and open minded, a female who believes that nothing is impossible and always grows and explores with no boundaries. A female who is connected to and conscious of all things. When she is wearing my garments, I want her to feel timeless. I want her to feel an abundance of love and kindness and effortlessly confident in her own skin,” says Joanna Yi, designer and founder of The Open Book. “Every concept I create represents a process for healing my relationship with my inner self. I explore many types of healing modalities for creative expansion, including but not limited to art, history, philosophy, meditation, yoga, and quantum physics. My motive in life is to help others feel more love and wholeness through any creative medium that I can use to express that message, with fashion design as my base.

The fashion market has been defining itself by what it can gain in clout and surface profit, but it is becoming more apparent that there is abundant gain to be had in adopting a mode of consumption that privileges one’s connection with the self, and, in turn, others. Trends shouldn’t be wholly minimized; they allow us to play with clothing and become emblematic of the period in which they’re born, placing a timestamp on the generation’s era of fashion. But just as fashion has long preceded us, it will long succeed us, a continuation that’s indicative of an element of timelessness.

“Honestly, when I was in my 20s working as an assistant designer in Seoul, Korea with crazy fast paced working conditions, I couldn’t understand the real meaning of ‘classic’ because I had to design new styles everyday under the corporate’s seasonal sales plan,” says designer Mijeong Park. “Now I understand how difficult it is to make classic pieces. Without history, philosophy, introspection, it can’t be classic.

“The good thing is, not like the Baby Boomers or Generation X, Millennials do care about themselves. And they are willing to learn and listen to themselves. Maybe the uncertainty of their lives and futures causes them to look inwards and receive a higher level of self-awareness. They are not like traditional consumers who buy based on advertisements or go to department stores. They would rather research what they are interested in and, if they believe it, they will want to experience it. And they are brave enough to do it and not care about someone else’s eye. They can set their own standards.

“We don’t want to be a cool brand that customers are raving about. That is not ours. Rather than the instant success, we’ve decided to grow based on customer’s trust.”

Consumer tastes and behaviors are as hard to predict, as is what a designer may create for their next collection, but we can consistently rely on the fact that in making and consuming fashion we are inevitably saying something—even if it is that we couldn’t care less about it. With this grounding principle, it seems the only thing left to uncover is what it is that we want to say with what we wear. Emerging designers of the current generation are inspiring consumers to revisit this question, which, in effect, is calling for us to revisit ourselves. Embracing this empowering mode of “selfishness” may just be the fresh approach needed to reignite the evocative spark of fashion and give it a refreshing, unfeigned voice to speak above the rest.