Ahead of Waters's new essay collection, 'Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder,' the writers reminisce on glory holes and redeem Warhol's legacy for Document S/S 2019.

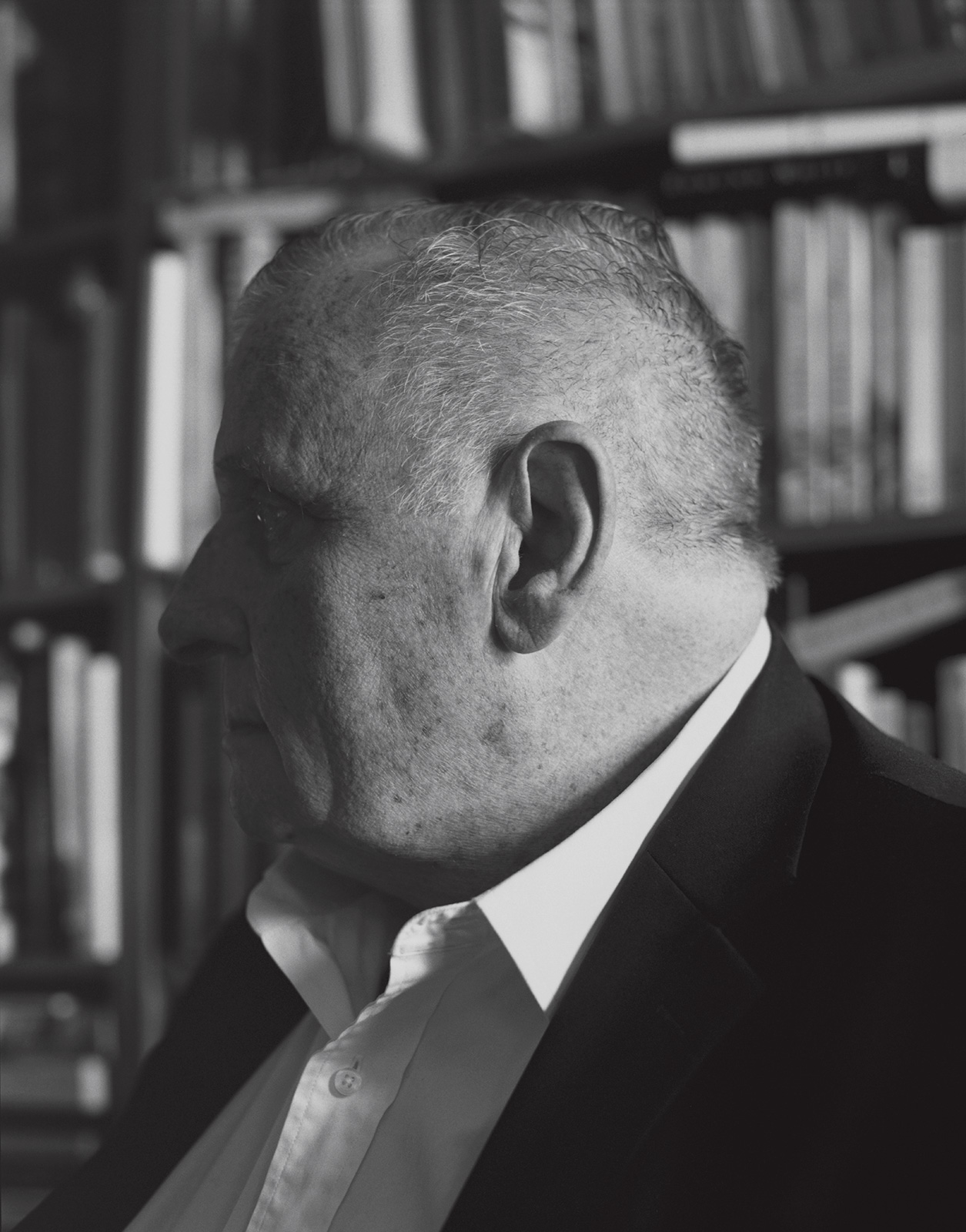

John Waters begins his upcoming collection of essays, Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder, bewildered by his own respectability. Once referred to as “the Prince of Puke”—and forever the champion of the underground, the fringe, and the midnight movie crowd—his mind was behind Divine eating dog feces in Pink Flamingos and her rosary bead anal penetration in Multiple Maniacs. Today, at the age of 72, Waters finds himself institutionally ordained, with two New York Times bestsellers and films hailed at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. (He’s also a regular college commencement speaker.) It is from this vantage point, reached through a gleeful compulsion to transgress, expose, shock, and repulse, that Waters bestows wisdom and cheeky advice underpinned by clever, sometimes unsettling, insight.

To discuss his latest work, Waters pairs up with Edmund White, who recently joined the ranks of Philip Roth, Cormac McCarthy, and Toni Morrison as a recipient of the PEN/Saul Bellow Award for Achievement in American Fiction. White is a seminal queer voice in literature and a prolific writer of memoir, biography, and fiction. Like Waters, he finds himself canonized after experiencing life on society’s margins. Co-author of the first edition of The Joy of Gay Sex (published in 1977), and author of the iconic A Boy’s Own Story, White is revered for his candid recollections of childhood isolation in the 1950s Midwest, as well as New York’s underground gay sex scene and the AIDs epidemic. His half-century writing career continues unabated with the literary memoir The Unpunished Vice: A Life of Reading, published last year, and his forthcoming novel, A Saint in Texas.

Here, Document eavesdrops on a chat between two living legends as they decode death, sexting, and Andy Warhol’s lasting influence.

Above The Fold

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

Document: Hi, it’s John from Document Journal. Is anyone there?

John Waters: I’m here. John Waters.

Edmund White: Hi, is this John?

John Waters: This is both Johns. It’s like a hooker convention.

Edmund: Great! [Laughs] How are you?

John: I’m well. I’m nervous since this is my first interview for my new book.

Edmund: Oh, I love this book. I thought it was so great.

John: Thank you. I’m also nervous because you’re one of my favorite writers. You being the first [interviewer] makes me doubly nervous.

Edmund: Oh, okay. Well, I think it’s a really funny book. I mean, there are so many great lines in it. And so many things fascinate me, like your chapter about Warhol—when you say nobody will get a fame that original again in our lifetimes.

John: I agree with that, you know. Of course—I wrote it. I think that was me thinking about sticking up [for Warhol]. Why is he the villain all the time now—in every movie, in every book—when he made every person famous? He was the ultimate person who thought about branding. So I’m just kind of sticking up for him from beyond the grave.

Edmund: I like that. I feel the same way toward him, and I think that all of his originality is challenging everybody’s fixed ideas about what art is. It’s a single work of art? Okay, he does multiple. It’s done by one person? Okay, you get a group to do it. There was a moment when he would sign anybody’s things for $10. He set up a stand on Sheridan Square where you could bring your iron or whatever and he would sign it.

John: I know. Salvador Dalí ruined his whole career by signing anything at the end, and Andy made it better. Salvador Dalí was just greedy.

Edmund: Yeah, and his wife, too.

John: The only person who did everything before Andy, in a way, was Duchamp. He did everything first. It was amazing.

Edmund: Yeah, he was great. But I hate Dalí. I love to make fun of him.

John: In the very beginning I liked him. I’ve done things with the Dalí Museum in Florida before. But he ruined his own career through bad publicity.

Edmund: Through greed, yeah. Of course, you know so much about art and collecting, and I thought your chapter about the golden age of monkey art was so funny.

John: That took a lot of research. But it really did start with Betsy, in Baltimore, the first [monkey artist] I knew about who became a national star. It is really the only genre of art that isn’t so expensive that you can’t buy it. So I’m tipping people off: This is the new thing to buy.

Edmund: I thought that was hilarious. And I like the way that you compare the various monkeys to living artists.

John: Yes, but they’re all artists I really like. And if you take the trouble, you can Google those monkeys and you’ll see some are like Twombly, some are minimalist, some are abstract expressionist. I’m just trying to think what their career would be like in the current art world today. I only make fun of things I like.

Edmund: Definitely, and you’re very explicit about things you don’t like. You call Studio 54 awful.

John: Well, I always hated it there. And I could get in. I was a Mudd Club boy. Disco sucks, you know? I liked the punk rock clubs.

Edmund: Right. Another controversial thing you say is that Andy Warhol’s movies are his best work, and I agree with you.

John: They’re the most radical.

Edmund: Most radical.

John: And one day, when collectors have frames in their walls for video art, they will be seen for what they really are: a still and a movie put together—which is really radical, because he went back to the beginning of movies and stopped it.

Edmund: I know. Absolutely. And those weird things like showing a man asleep for eight hours.

John: Empire was really the best. It was such a good idea that Andy even gave another director a co-credit, which he never did any other time. So that’s pretty amazing. Jonas Mekas filmed it.

Edmund: Yes. He recently left us.

“I saw an ad in a magazine recently—you can now send away for a portable glory hole, and you just put it between any doors in your house. That’s hilarious. Poor cleaning people: ‘Pay no attention to that glory hole.’”

John: I know. I love Jonas. Jonas saved my life. I was a 15-year-old kid in Baltimore reading his column in The Village Voice. That’s how I knew about underground movies, that’s how I came to New York, everything.

Edmund: In your chapter about Provincetown, something you say is, ‘I’m against mandatory fixed sexual identity.’

John: I kind of am. I’m not a separatist. I know a few people who are gay and then they got girlfriends for awhile and the gay world gave them so much trouble. Well, I think they’re allowed to come in, too.

Edmund: I have lots of friends who are bisexual, and gay people always go, ‘Oh yeah, sure.’

John: No, but that’s not true. There are bisexual people. I wish I were. Didn’t Woody Allen say it doubles your chance for a date?

Edmund: Doubles your chance for a date.

John: The thing is there are people, especially young people, who don’t care. Some of them are gay for a week, some of them aren’t, some of them are gay forever. Even people who transition—I think they should be able to [transition] back if they want to.

Edmund: Women who were afraid of men when they’re young were called LUGs, lesbian until graduation.

John: I know that one. We owe lesbians a great thanks. They were soldiers for Act Up and they couldn’t even get AIDS. And they went to war with us, so they deserve great credit.

Edmund: I know, that is so wonderful. Before that, there was such a divide between gays and lesbians and then they pitched in and fought for us.

John: Yeah, and I think we never fought for them enough.

Edmund: Absolutely not. I also especially loved your chapter on Cry-Baby. That was your big Hollywood film right?

John: Well, I guess it was. Serial Mom was a Hollywood movie, too. After Hairspray, they all went through the Hollywood system completely. We were pretty loose on Cry-Baby. That was the only movie I ever made where, if the whole cast walked into a restaurant, people would run. They didn’t ask for autographs. They were just kind of horrified.

Edmund: ‘Martha, let’s leave right now.’

John: ‘Let’s get out of here.’ Right.

Edmund: I had never known about the existence of Kiddie Flamingos.

John: It’s not in my filmography. It was a video art piece. I got so sick of all the reviews of movies that said, ‘It’s so John Waters–esque.’ They were usually movies I hated because they were just gross, without being funny. So I thought, ‘Well, maybe I should imitate my censors and censor myself the most, and go back and make Pink Flamingos into a children’s movie.’ Because they’re similar. Many, many children’s books are gross-out books. I just took out all the dirty parts. And the kids didn’t know. They liked reading it, and they liked playing the parts. But the parents knew, so you could see them cringing, thinking, ‘Oh God, I hope they’re not gonna talk about the fucking chicken.’ [Pink Flamingos features a famous scene in which two characters, Cookie and Crackers, crush a live chicken between their legs during sex.]

I’m thinking of going further. I think I should do Female Trouble in an old-age home and Polyester in Braille for blind people. You know, I could redo them all.

Edmund: I loved the chapter you wrote about dying, and that you wanted to be buried with all your friends, and it would be called ‘Disgraceland.’

John: We call it that now. We all bought plots there. Mink Stole, Pat Moran, Dennis Dermody, me, lots of people. There are a few more I’m trying to lure in. Divine’s there anyway.

Edmund: That’s wonderful. And I had also never known about the Hungry Hole.

John: Oh God, that one. That place was in San Francisco, and I never went to it either, but many people told me about. And it did have glory holes for asses. Imagine that today! You think back on it like, ‘Whoa! Oh God!’ And I always pictured they should’ve had nurses there giving out gamma globulin shots. But I even have the logo for it. There definitely was a place. We had clubs then!

Edmund: Definitely. I mean there was a club in New York that was just called The Glory Hole.

John: Oh yeah, I went to that one. It was a chain. They had one in San Francisco, they had one in Los Angeles. I saw an ad in a magazine recently—you can now send away for a portable glory hole, and you just put it between any doors in your house. That’s hilarious. Poor cleaning people: ‘Pay no attention to that glory hole.’

Edmund: I met one of my lovers at The Glory Hole.

John: Really? Not that many people got lovers out of The Glory Hole.

Edmund: It was only because he was so sexy in The Glory Hole and then he invited me home to his apartment. And he had all the same books that I had and I thought, ‘Okay.’

“Some young people are gay for a week, some of them aren’t, some of them are gay forever. Even people who transition—I think they should be able to [transition] back if they want to.”

John: At The Glory Hole, all you could see was their dick, really.

Edmund: Well, that was enough.

John: I always thought it was scary in there because, suppose I just blew Rex Reed? You couldn’t tell whose dick it was. That was my fear.

Edmund: You’re right, you’re right. But going back to the book, I thought it was maybe self-serving, or maybe just kind, to say, ‘My fans are so great; they’re so cool and sexy.’

John: Well, they are. I still do my spoken word show a lot. I did 17 cities on the Christmas tour in 21 days. I see them all. They get their roots done. They’re all ages. But they dress well. They’re smart. They bring me great presents. My fans are a cut above. I think yours would be, too.

Edmund: It’s true, but mine tend to be older gay men. I gave a talk last weekend at a museum in New Orleans, and there were all these poor, old gay men who crawled out from under the rocks.

John: Well, they’re home reading. Good.

Edmund: Exactly. The only exception to that was my Paris book, The Flâneur. I had always read at the Smithsonian in D.C., and there would always be the same 20 elderly gays. But for The Flâneur, it was all the kind of rich, heterosexual couples who love Paris.

John: Well, that’s great. You see, you’re crossing over.

Edmund: I was crossing over and they had to move the event to the Department of Agriculture.

John: Oh God. Did you get any farmers?

Edmund: No, alas. But they had 700 snowy-haired couples who all bought five and six copies as stocking stuffers.

John: Oh, that’s good. I like the kind of events where the book comes with it.

Edmund: In your book, I thought it was funny where you talked about everybody cruising with instant messages now, and if the bad grammar means you’re butch.

John: Well, I’m wondering—does it? Like, for phone sex, but now you’re texting. Is misspelling butch?

Edmund: I think it is.

“‘If you’re a Syrian refugee, is anything campy? Is there anything so bad it’s good?’ And then somebody said to me, ‘John, that’s an elitist comment, because, yes, I bet they do crack jokes.’”

John: Or rough trade? How do you tell if you’re texting? I guess poor English.

Edmund: I remember in the 1960s, in the early days of gay porn movies being shown in theaters, I remember going to one and there was this truck driver who was getting blown, and he said, ‘That is truly excellent.’

John: Well?

Edmund: I thought, ‘That doesn’t pass the rough trade test.’

John: Right. ‘Truly excellent.’ Well you never know what’s butch. Even in the bear community, I sometimes think, ‘Is fat butch now?’ I guess. I don’t totally get that.

Edmund: Let’s talk about your chapter about Provincetown and all the different groups who go up there for special weekends.

John: Oh God, it’s unbelievable.

Edmund: It seems like the bears are thinning out because they’re all having heart attacks, because they’re overweight.

John: They get fatter though. I’ve noticed that. But they still have a big event. Then they have Daddy Week and I was like, ‘Oh, please, I hope nobody thinks I’m there for that.’ And then Gay Pilots Week. I thought, ‘There’s enough of them?’ I thought it meant people dressed like pilots, but it doesn’t. But, then, I’m always out of the loop. I’ve lived in Provincetown for 54 summers. I flew in last summer, and it was all gay men on the plane, with a gay pilot. And when he landed, he said, ‘Welcome to Provincetown, gentlemen. See you at Tea Dance.’ I said, ‘Excuse me, I’m gay. I’ve been here 53 years. I have never once attended Tea Dance.’

Edmund: Great.

John: I felt like I was being stereotyped as a gay man.

Edmund: That’s funny. Another one of your controversial opinions is that you hate The Beatles.

John: Well, I did hate The Beatles. They were too damn cheery for me. When The Beatles were out, I liked The Rolling Stones better. But now I like The Beatles. Things change your musical taste. I like punk rockers and I still host a big punk rock festival. This is the fifth year I’m doing it, in Oakland. It’s called Burger Boogaloo. It’s great. We had Iggy, The Damned, lots of great people. Those are my people sometimes, and punk is kind of down-low anyway.

Edmund: Good for you. Well, I don’t have too many more questions.

John: That’s all right. I’m glad you were the first person I talked to who’s read the book.

Edmund: Tell me about your relationship to irony. How do you feel about irony?

John: Well, in the movie Pecker, I said I wanted the end of it. Irony is snobbery, but I am an irony dealer. So I plead guilty I guess. I think I say this in the book: ‘If you’re a Syrian refugee, is anything campy? Is there anything so bad it’s good?’ And then somebody said to me, ‘John, that’s an elitist comment, because, yes, I bet they do crack jokes.’ So I don’t know. It’s not up for me to decide that. But I wonder sometimes. It is an elitist taste, irony.

Edmund: I think so, too. And you deal with it sparingly.

John: Well, I really do like the things I address—not because they’re so bad, they’re good, but because they’re so good, they’re great to me. But I recognize that others might not agree.

Edmund: Andy Warhol said that pop art is a way of liking things.

John: It is, certainly, and everything in this book that I write about I do like. I like the whole Hollywood experience. They were fair to me. I like the art world. Everything. I’m even trying to like dying and figuring a way out of it.

Edmund: Good for you. We don’t want to be ironic about our own deaths.

John: It’s just me trying to be optimistic—that I’m gonna claw my way out and I know where I’m going to end up. Isn’t that the ultimate ‘glass half full’ kind of guy?