Set in a Silicon Valley multiverse ruled by apps and algorithms, Schulman's latest book 'Come With Me' reveals the myriad consequences of our gluttonous hunger for knowledge.

“What do you want to know?”

It’s the question that sets in motion much of Helen Schulman’s fantastic and timely new novel Come With Me. It’s an age-old question and one that, for most of history, could be answered pretty simply: More. In the Digital Age, however, we’re awash in so much information and data, that our quintessential hunger for knowledge verges on gluttony. Indeed, today, the question we might be better served asking ourselves—and the one that Schulman deftly explores in her new work is: How much do we really want to know—about our family, our friends, and ourselves?

Set in the tech bubble of Palo Alto, the novel revolves loosely around the lives of the Reed family. Amy, the middle-aged mother of three, works for the son of her college roommate, a young Mark Zuckerberg-style computer genius named Donny. Though not terribly unhappy in her current life, Amy can’t help but wonder what might have happened had she made different choices. It’s a human trait most of us can relate to. But Donny has a very 21st-century take on the dilemma: He develops an app, called The Furrier, that uses personal data and a patent-pending algorithm to give users a peek at the parallel lives they could be leading. Amy serves as reluctant guinea pig, and must contend with the insight bequeathed—for better or worse—by the Furrier. Meanwhile, her husband Dan, an out-of-work journalist, spends his days gorging on information, researching leads to stories he never seems to get around to writing. Maryam, the magnetic award-winning photojournalist and trans woman who Dan befriends, insists on flying all the way to Fukushima, the Japanese city devastated by a nuclear meltdown, in search of Truth. And, back in Palo Alto, a sudden tragedy will shake the Reeds to the core, reminding each how little one can know of another’s inner life.

A good novel about technology will shed new light on what it means to live in the digital age, today. But a great novel on technology reminds us of the age-old questions that have plagued humankind since the first one of us picked up a rock. Come With Me belongs distinctly in the latter category. We caught up with Helen Schulman to discuss the seeds of the story, her process, and what it’s like working in the Age of Information, when her “job is to make stuff up.”

Above The Fold

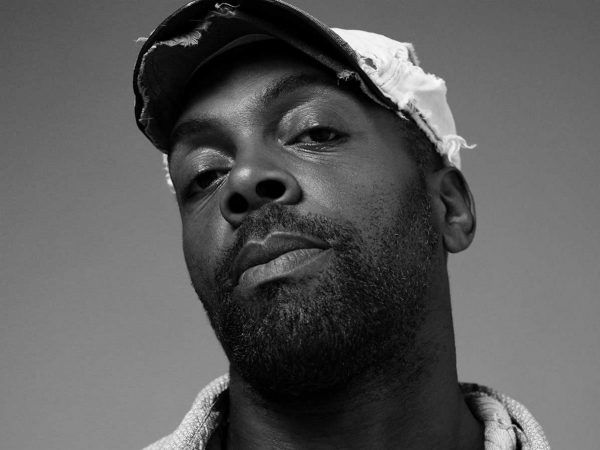

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

Hayley Phelan—While reading this novel I was sort of blown away by how much was packed into it: Silicon Valley, tech bro startup culture, teen suicide, young sexuality, the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, marriage, motherhood, trans identity… And it was told from multiple points of view! What was the original jumping off point for the story?

Helen Schulman—Bruce [my husband] grew up in Palo Alto, and so I’ve been going to Palo Alto for all these years, watching it all change. He has a very good friend who works at Google, and one day she invited us on a tour. I really knew nothing about it. And I was so struck by this weird world where you could get your dry cleaning done, or if you wanted to do yoga you could do yoga. If you wanted to sleep, there was a sleeping room, a tai chi room…It was this place that one one could leave. I was then interested in Sheryl Sandberg. Now, as a Jew, I’m not interested in Sheryl Sandberg. But at the time I thought, ‘Wow, it’s so interesting: This woman is like a den mother to all these baby boy geniuses, and has to try to corral them.’ So, I thought I could write something on that. I wrote a story but I couldn’t sell it, and just kind of passed around for a few years.

Then, I read a book by Max Tegmark about the multiverse theory, and it just blew me away. This is kind of what my brain does all the time. And so then, there was a piece in the Times about how the guys in Silicon Valley have all this power, but they don’t know what to do with it. They were reading science fiction to get ideas. Then I thought, ‘Oh wow, what if they read about multiverse theory?’ And that’s how I came up with the idea of The Furrier.

Hayley—It’s funny how you say your brain kind of naturally creates the kind of multiverse that The Furrier does with algorithms. While reading all the different scenarios that The Furrier spit out, it struck me as being very similar to the process of fiction writing, where you take one fact, or idea, and from there a whole universe emerges.

Helen—Yeah, I mean, I really have all these stories in my head going all the time. I go to the gym a lot and I walk across the park to get there and when I come back my husband is like, ‘What’s the weather?’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t know. Don’t ask me that! I’ve not been on planet earth for those couple of hours.’

“We have this big machine now that nobody knows how to handle, we don’t know what it can do, and we haven’t figured out the rules.”

Hayley—How do you pick what stories you want to actually write?

Helen—At some point, you just do. It’s almost arbitrary.

Hayley—Tech has featured prominently in both your recent novels. What fascinates you about it? What keeps you up at night?

Helen—Well, it’s changed everything. We have this big machine now that nobody knows how to handle, we don’t know what it can do, and we haven’t figured out the rules. I don’t do much, I don’t have social media. I use my computer to write on and research on. I don’t want to sound bitter because I used the internet so much in researching this book. I could get menus and recipes from Japan. I could Google Maps Amy’s run in Palo Alto. I mean, it was amazing.

Hayley—At the same time, it can be information overload.

Helen—Absolutely. Everything you read, you then Google again. If you’re a person who is interested in things it’s almost impossible not to. If you’re a person who’s scared to write and is interested in other things you could waste your whole life just going down that hole. In a way, Dan is the closest character to that, he’s so consumed by it because his days are empty. For him, he didn’t have a job, he’s frustrated, he feels like such a loser, there was nothing else to do but continue to hunt.

Hayley—Speaking of Dan, I thought you handled his midlife crisis so perfectly, in a way that was unsparing—and at times, cringeworthy—but still sensitive.

Helen—Dan is complicated. I had to work very hard to have sympathy for him. But I do think he’s in the middle of something very difficult. He hasn’t felt anything in so long, and it’s from that place that he’s making choices. Still, I don’t think Amy would ever do [what he did]. She might fantasize about it, but she wouldn’t do it.

Hayley—Maryam, Dan’s crush, is such a fascinating character. I had so much fun reading her! I appreciated the way you handled her identity as a trans woman, neither underplaying nor overplaying it. I felt like she got to be a whole person rather than having her identity flattened to this one signifier.

Helen—Thank you for saying that because it’s a point of contention. The trans people in my life are just like everybody in my life, they have a whole world. They’re not just one thing. I thought, why can’t I have a character that’s just like everybody else and not make it all about her being trans all the time. Because by the time he encounters her she’s so firmly grounded in who she is and it’s part of her. It’s like—for you and I—being women is part of who we are but it’s not the only thing or the most important thing about us.

[Maryam] has a really complicated history. She’s really an outsize character but that’s part of what Dan is attracted to in her. She’s got her own world to contend with. In my own life I love people who are superlative. They just kind of eat the world. To me, that’s what she does. In some ways, she’s extremely selfish, but she’s free.

Hayley—A lot of your books revolve around the intricacies and intimacies of family life. How much do you pull from your own family?

Helen—It’s funny because my first novel [Out of Time] revolved around two parents and spanned decades. I was 31 when it came out, and didn’t have kids yet, but people would always ask me if I was a mother. I think I could always sort of see ahead like that. Obviously, the family in [Come With Me] came from my brain and not someone else’s, but it’s not our family. I don’t live in Palo Alto. My husband isn’t out of work. I don’t have twins.

“In my own life I love people who are superlative. They just kind of eat the world.”

Hayley—I think it’s interesting how a lot of contemporary readers assume that a novel or a character draws deeply from personal experience. They almost feel cheated if it doesn’t. It reminds me of something that Maryam says, when Dan suggests she wouldn’t be able to understand because she doesn’t have children: ‘I really hate that shit, Dan. As if we all have to be identical to understand the texture and taste of what are bedrock human feelings. One might think that you did not believe in the divinely human and universal qualities of compassion, sympathy.’

Helen—I’m a fiction writer and my job is to make stuff up. We’re living in a world right now where some people say, ‘You can’t write that, you can’t write my story.’ And many writers are writing autofiction. But the idea of inventing and creating something that I don’t necessarily live in or have experience in, is what it’s always been about for me. I have nothing against auto fiction. I just don’t have anything interesting to say there. But my head is full of stories. I like going there and I love to read that too.

Hayley—I think it ties back into some of the themes explored in the book. The question, ‘How much do we want to know and how much is too much?’ Now that we have access to so much information about an author’s personal life, it’s like we can’t judge their work without throwing that into the equation.

Helen—Yeah, for me personally, I just don’t have that eagerness to know about an author. I don’t care who wrote it. When I was a child, this sounds so dumb, but I didn’t really occur to me that people actually wrote books. It was almost like God put them down.