The artists discuss streetwear, Orientalism, and the shifting demands of the art market for Document S/S 2019.

This conversation appears in Document No. 14, available for pre-order online now.

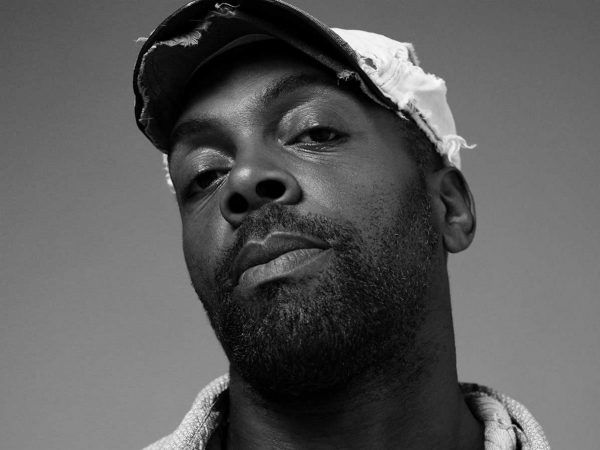

Over the last two decades, Japanese streetwear has blossomed into an undeniable movement in modern fashion, and that’s largely thanks to roots planted by Hiroshi Fujiwara. In the early 1980s, luxury labels like Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto dominated the Japanese fashion scene, and it wasn’t until the latter half of the decade that a young Fujiwara set out to restructure the aesthetics of Japanese youth. Armed with an influence born from his love of skating and hip-hop (which he experienced firsthand during visits to London and New York City), Fujiwara helped lead Japan toward what it is today: home to some of the industry’s most celebrated streetwear brands. He’s rightly called the “godfather of Japanese streetwear,” and under his label, Fragment Design, he’s demonstrated his technical prowess, innate precision, and keen eye for functionality through hundreds of collections, capsules, and collaborations.

Fujiwara’s most recent endeavor was participating in the latest iteration of Moncler’s Genius project, creating a series of technical outerwear. Adorned with his signature lightning-bolt insignia, the project is a reinterpretation of Moncler’s historic down jackets. Fujiwara is clear about his design intentions: He only creates products that he would wear, so when we see his designs, it’s an intimate look into his expansive creative process.

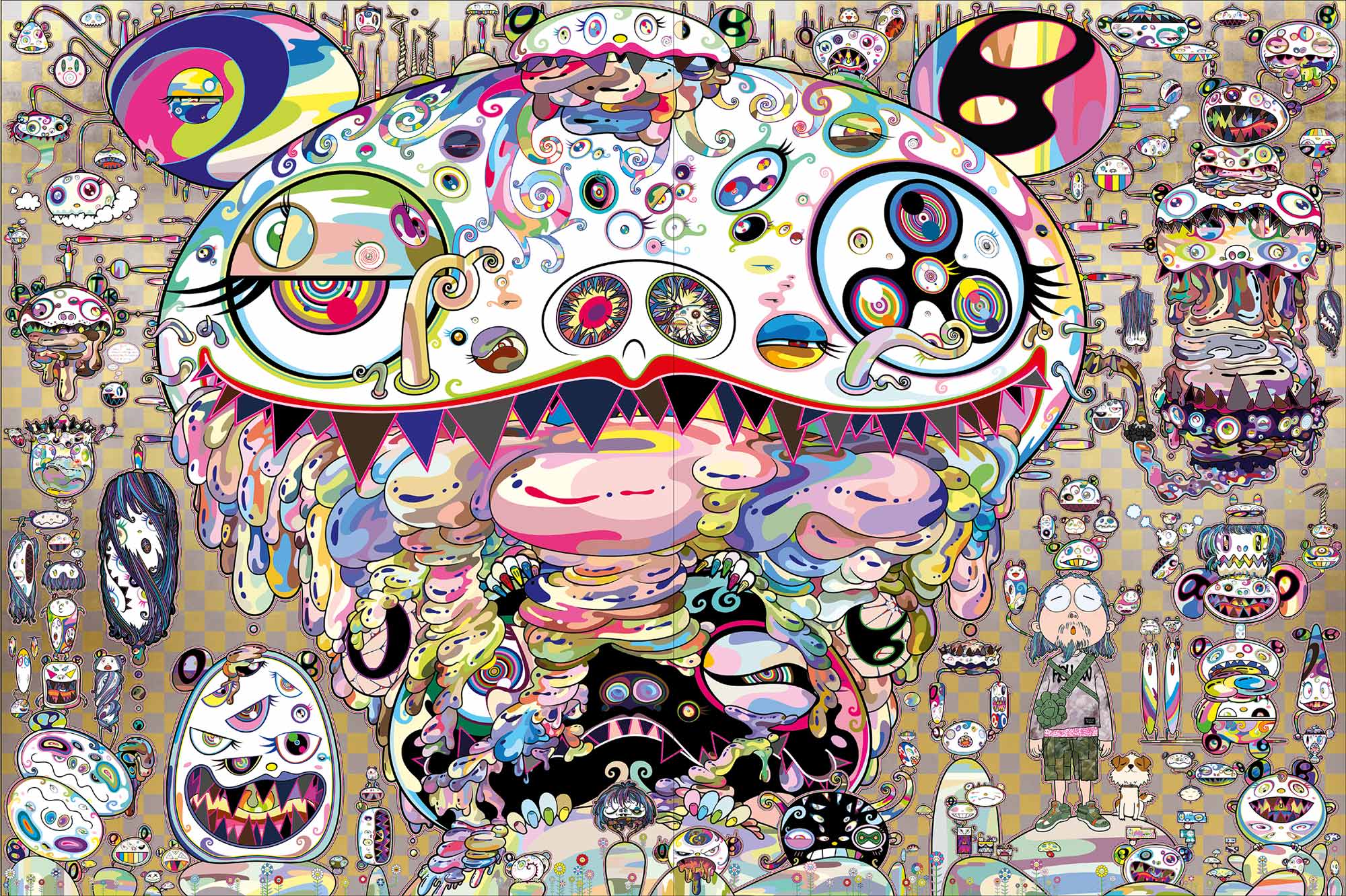

Fujiwara’s friend Takashi Murakami, meanwhile, is widely considered a grandmaster of contemporary art. It was also nearly two decades ago that Murakami formally presented Superflat, his new genre of pop art, which blends traditional ukiyo-e wood block prints with allusions to manga and anime. It’s also permeated the artist’s colorful and psychedelic sculptures, illustrations, and paintings. Like Fujiwara, Murakami has participated in iconic collaborations, from creating album covers for Kanye West to producing famed accessory collaborations with Louis Vuitton, which featured Murakami’s vibrant rendition of the LV monogram.

Fujiwara and Murakami have visibly altered their respective landscapes while perfecting the art of merging mediums. They’ve both reached formidable heights and proven hugely influential, yet they’re not afraid to surprise with unexpected, even quirky, projects. Here, they speak about their changing industries, the shrinking gap between their creative fields, and how they’ve adapted accordingly.

Above The Fold

LVMH’s Final Eight

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Document—Do you think fashion and the clothes we wear are important?

Takashi Murakami—Honestly, I don’t have a good sense of what the relationship with clothing is, nor is that what I’m focused on. My way of making things was painting and sculpture. Then I saw how people like Kanye West and Virgil [Abloh] became involved with clothing. During the process of making a promotional video with Kanye, I saw that you can take the same approach to clothing. I recently have had a strong interest in it as one aspect of making things. But the context in which I’m thinking about it is not at all in terms of creating apparel, loving it, and deciphering my relationship to it. So even now it always seems like playing dress-up. I don’t have any internal value telling me, ‘Oh, this outfit looks cool.’

In thinking about the flow of fashion history through this time period, I brainstorm in my head about what would be well received or interesting to do. But it doesn’t go beyond that. It’s Hiroshi who’s long been involved with fashion, so perhaps this kind of question is better directed toward him.

Hiroshi Fujiwara—I think what you said about your approach from the perspective of art was very fresh, important, and interesting. I appreciate you saying that. When you were talking about people like Kanye West being involved with fashion while making music, I thought this is something relatively common. There’s been a connection between fashion and music for a long time, as they are similar in nature. But as you might expect, when it comes to things like contemporary art, growing to like fashion and trying to seriously incorporate it or to play around with fashion are new concepts. For me, it seems to raise the value of fashion itself, for which I’m appreciative.

Takashi—But we collaborated in the past on the exhibition Hi & Lo. Starting at that time, I think that you and I somehow created a bridge between us.

Hiroshi—Yes. But I felt like you built out that bridge as the artist, and this made me very happy.

Takashi—The things Virgil did [with Kanye and Don C in Chicago] closely resemble what was happening with the Kichijoji technoculture in the ’90s. I initially misunderstood Ura-Harajuku as something unapproachable, that its goal was to be cool. But when I realized that this wasn’t the case, my nervousness dissipated. So it wasn’t that I was looking down on things, but it was more of…

Hiroshi—It’s not looking down on, but even if we go back a step from fashion to things like so-called modern art and otaku culture, it was you who created the bridge connecting these things.

Takashi—Well, despite my efforts I ended up being disliked by the otaku industry. [Laughs] But in regard to Orientalism, I think for those living in Japan, there is an underlying feeling of wanting to stop the caricaturing of their culture. But in the American contemporary art world, I also saw that there was an intense desire for this culture.

Hiroshi—Over there?

Takashi—No one had done it, so while I was doing it, I was internally wondering if it was okay to do. But at the same time, I was re-studying Japanese art history and having my work looked at by people like the Japanese art historian Nobuo Tsuji. And midway through doing this, I started to do a course correction so that there was consistency with the overall flow of Japanese art.

Hiroshi—To approach it seriously.

Takashi—That’s right. [Laughs] Like anime, fashion can be seen as insincere or only for amusement. So I tread lightly while hoping that people don’t get angry with me.

Hiroshi—I think that’s okay for fashion, right? I think that’s actually what comprises fashion.

Takashi—I see.

Hiroshi—I feel like there is a high hurdle for art, and that it has many rules you can’t see. It might have been like that in the past for fashion as well. Perhaps with the emergence of people like Kanye and the close relationship to music, those kinds of barriers were able to be sufficiently removed. This is precisely why someone like Virgil was able to become a designer for major brands and work with people like me. I think that’s where it started.

Takashi—I think you’ve recently been accelerating the pace of your collaborations.

Hiroshi—It’s been like this since I began working internationally with brands like Moncler and Louis Vuitton. Collaborations are all I have. I have nothing of my own, so I can only work with others. That was the case when I worked with you on Hi & Lo. I have nothing original, so my basic style is to join with others who allow me to play with them on their turf. I’ve been like that for a long time.

Takashi—I see. At a glance, it seems like you’re moving at great speed. These days, speed is also very important, so I thought you were truly changing yourself to match the times.

Hiroshi—I feel like I’m changing in a good way, and enjoying myself alongside those who will play with me. [Laughs] I think part of it is the generational difference. The younger generation is so active. Is that kind of lateral movement not as prevalent in the art world?

Takashi—Recently, yes. Two years ago, when I was tracking Virgil’s trends, I was talking to a guy named Ishida at a store called Cherry in Fukuoka. We discussed recent fashion forecasts. I thought to myself, ‘I get it. That’s another way to look at things.’ You can try to apply that point of view to modern art, but it’s a totally unchanging world. And within this trendless state, you have someone like Kaws, who is the epitome of street culture. He is completely unrelated to Western museums and critics. His activities are focused on Asia. Kaws is moving the contemporary art scene, or should I say the market itself. In a manner of speaking, Kaws also emerged from the bridge with Japanese culture. In the past, myself and other Japanese artists were obsessed with [Jean-Michel] Basquiat, New York, and overseas artists. They were looking at Asia and only seeking hybrids; there weren’t any really large themes.

Hiroshi—So it’s not that what Kaws is doing is fusion with fashion, but that contemporary art itself has become a lot like fashion?

Takashi—The moment that the Chinese art market opened, the market’s scale suddenly increased in size by a third. Because of this, there is a state of confusion regarding the course of action. I honestly think that this market-led period is quite reminiscent of the period of contemporary art history when [Julian] Schnabel emerged, the era of new paintings. It’s a state of disorder.

Hiroshi—People like me who have a dark way of thinking see that within this state of confusion, the price of Kaws’s work is greatly increasing. So I’m looking forward to seeing how things pan out.

Takashi—That’s true, but it can also be said that there is a mood of imminent recession.

Hiroshi—The recession doesn’t seem to be coming.

Takashi—When you ask Chinese feng shui masters about this, they say it’s definitely not coming. [Laughs] The reason being that the Chinese Communist Party absolutely won’t allow it.

Hiroshi—Gotcha.

“I have nothing original, so my basic style is to join with others who allow me to play with them on their turf. I’ve been like that for a long time.”

Takashi—The Communist Party and the Chinese economy support one-third of the world’s economy, so they are saying they won’t accept it. But if a recession does occur and prices decline in the work of older generation artists like myself, new buds will definitely be born. So for us, it feels like the start of an unhappy period, the beginning of an era.

Hiroshi—So when things change in the art industry, items from the past are discarded?

Takashi—Not thrown away, but—how should I put it?—I think it’s an industry that’s more susceptible to trends than you would think. It wants to create trends and follow them.

Hiroshi—I see.

Takashi—Recently things have changed again, especially from 20 years ago. Now there are a lot of individual museums, and there’s starting to be a scramble for customers. And as you might expect, people are beginning to look for hit-making content. There is a need for things that can sell in museum shops, and this nuance is totally different from how art used to be.

Hiroshi—Meaning that when the market got bigger, everyone awakened to money-making potential, or that this aspect has become necessary?

Takashi—Honestly, the reason people like Kaws are able to be consistent hit-makers is that the industry is not able to keep up with these needs. Artists like myself who have the ability to merchandise have the potential for rapid growth. I think this too might be something that people will soon become tired of. But I believe this can also be said for fashion, where, armed with a visa, you move from country to country. Do you think that’s the case for fashion?

Hiroshi—I don’t really feel like that’s currently the case with fashion, but I think the situation for artists surrounding merchandising that you mentioned might be the same in the music industry.

Takashi—I see.

Hiroshi—With music, you can no longer get by just producing CDs or performing live. Those who are able to create products that sell at their concerts are the ones who survive. It seems to me that this situation is reminiscent of the art world.

Takashi—This could be a different context, but I think Kanye might have started desiring to heighten his prestige because he had always been producing concert merchandise. Virgil had trained beside him, and became adept at combining various available elements to come up with something new, because they were always working under time constraints. So they combined this and that, and unveiled the mix that they produced. They trained in this for a while, and now that’s all they’re doing. When we talk about media mix, I think it might be the music industry that’s exerting various influence and bringing many changes.

Hiroshi—I feel that way, too. Virgil is doing a whole host of things now, but do you think he’s considering what he’ll do in a decade? It’s the same for me. Not that my products would stop selling, but I might get sick of it myself. I don’t think I’m looking at things with a long-term perspective.

Takashi—Really? In running my company, I’d be in trouble if I didn’t take a long-term perspective. Otherwise, I’d get behind the times.

Hiroshi—But that’s not only the case for art, right? In the past, you had to actually produce paintings to be viable. But now there’s merchandising, clothing, t-shirts, and offset printing; there’s many different options available, right?

Takashi—Yes.

Hiroshi—Different methods can be used to survive. Then, when the time comes, you can resume painting again. Don’t you think that’s possible? It’s different from old-school art, where you’d earnestly work on one painting.

Takashi—Apologies if this goes against what was said earlier: Every industry has a conservative mainstream, who will totally expel you if you fall out of favor with them. As such, you can’t lose the concentration needed to work on that one painting.

Hiroshi—But in a way, I also think you’re the type who has been abandoned by the old-school industry. And that’s fine, right? You started this way.

Takashi—Understood. But I don’t think that would happen to you, because you’re someone who started from scratch. Recently on Instagram curation sites, there are tons of pages featuring Ura-Harajuku culture, so even now people are rehashing this and reassembling this culture from 20 years ago. And this is something that you spread because you were an epoch-maker.

Hiroshi—But wasn’t it the same for you? I might have been an epoch-maker in that area, but I was ignored by the so-called real designers and major brands above me.

Takashi—Really?

Hiroshi—Yes, in the same way that people in the art industry and artists above you dismissed you when you emerged as a young artist. I’m not sure if that’s what happened to you, but I had the feeling that our situations were similar. Isn’t it true that you also initially received most support from those overseas?

Takashi—That’s right. But now it’s dicey as I became disliked by the conservative mainstream. Maybe they just don’t have time for me. They’re not dealing with me.

Hiroshi—[Laughs] But there’s a lot of people who properly recognize you, so I think the support from that side is strong.

Takashi—I’ve been doing touring museum shows in recent years. I just finished a North American tour of an exhibition last year, and later this year it will continue through Central and South America; it’s really like a circus. When I was offered the collaboration [with Louis Vuitton] years ago, factors like economic conditions were [also] shifting in a variety of ways. The reception of my work fluctuates based on the rapid transformations taking place in different countries, and it feels like the circus. That’s why I was asking if that was the case for you. But you’re really talented, so you might not feel that way.

Hiroshi—I think I’m the kind of person that always wants to work on something different, even though some of my old things might sell well elsewhere.

Takashi—That’s right. Last year, or was it this year that you did Pokémon?

Hiroshi—I did do Pokémon.

Takashi—A collaboration between Pokémon and The Conveni that I didn’t understand at all.

Hiroshi—[Laughs] Now I’m making Baby Star Ramen.

Takashi—Wow. Baby Star Ramen?

Hiroshi—I’m making new packaging for Baby Star Ramen to sell at places like convenience stores. It’s really low-end, but I also like doing lots of small things. The reason I’m allowed to play around with things like this is surely because of my large-scale work. It’s a good balance.

Takashi—I see. That’s wonderful.

Hiroshi—If people from abroad heard this conversation, they’d have no idea what we’re talking about.

“I make films as a part of the art business, but the film industry is not that profitable: everyone investing in their dreams to get closer to achieving them. This is also a big part of fashion.”

Takashi—That’s true.

Document—I wanted to ask if Mr. Murakami had any advice for Mr. Fujiwara in collaborating with a big legacy brand?

Hiroshi—Please give me advice.

Takashi—Don’t be modest. You’re already doing it. I’ve only worked with Louis Vuitton, so I want advice from you. I’ve been jealously observing your collaborations with brands like Moncler.

Document—What are your overall thoughts on streetwear?

Takashi—In the same way as when I entered the contemporary art industry, I’m studying Hiroshi and the history of Ura-Harajuku. I’m also looking at the context of price shifts for people like Kanye. My approach is a completely academic style, not the ‘real street’ of streetwear. My current interest is studying, so taking part in today’s talk with Hiroshi is an honor. But to be honest, I don’t really understand streetwear very well.

Hiroshi—The way I see it is that although for you it might just be the studying of street brands, in the process you’re gaining material and things to play with. It seems like you’re really enjoying yourself.

Takashi—I also make films as a part of the art business, but they’re a money-losing proposition. The film industry itself is not that profitable. Everyone is investing in their dreams to get closer to achieving them. In a different way, it made me think that this is also a big part of fashion.

Hiroshi—Yes, that’s well put. Very well put.

Takashi—Really? Thank you. [Laughs]

Document—What’s interesting to you in fashion right now?

Hiroshi—I’m always living in the middle of it so everything is interesting to me. There’s nothing new in particular that I could point to.

Takashi—I only started studying, and I’m really into Raf Simons. [Laughs]