Virgil Abloh and Anne Pasternak discuss a "new Renaissance" in Document's Fall/Winter 2018 issue.

Some writers have confessed they feel a sense of panic when faced with interviewing Virgil Abloh. I get it. For me, it’s not because he’s arguably the hottest fashion designer of our day. I’m fearing our conversation because he’s as free and fluid in his thoughts as he is in his designs, so it can be tough for the rest of us to keep up.

I’ve met Virgil a few times—first, through a guy whose creativity also knows no bounds, my friend (and Brooklyn Museum trustee) Kasseem Dean, a.k.a. Swizz Beatz. Swizz asked me to moderate a conversation that Virgil also participated in at Art Basel last December. Throughout, Virgil seemed like a reluctant participant. So why did he want me to lead this interview now?

Nevertheless, when asked, I didn’t hesitate to say yes. Why? Because Virgil Abloh is an enigma—and a carefully self-designed one, at that.

It’s hard to contemplate how someone so young— he’s 38—has done so much. Born in Rockford, Illinois, to Ghanaian immigrant parents, Virgil graduated from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in 2002, and the Illinois Institute of Technology, in 2006, with degrees in civil engineering and architecture. In his early twenties,Virgil negotiated a meeting with Kanye West while working as a DJ by the name of Flat White. (Brilliant.) Before long, he was designing Kanye’s merchandise, working as his style consultant, and art-directing his album with Jay Z, Watch the Throne (for which Virgil was nominated for a Grammy). Meanwhile, he was also starting his own fashion companies, selling dead-stock Ralph Lauren rugby shirts, and even interning at Fendi. By 2014, Virgil had launched his off-the-charts-hot brand Off-White, and in 2015, he was nominated for the LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers. He has partnered on projects with Levi’s, Nike, and Ikea. And now—wait for it—Virgil is the artistic director of menswear for Louis Vuitton, an appointment that shattered ceilings and sent reverberations through the fashion world.

To me, Virgil Abloh represents creative freedom in ways that few ever dream of, let alone realize. I wanted to figure out why Virgil has captured the imagination of so many people. I wanted to find out how he does so much and, more importantly, why he does it. And I wanted to know if his practice is really, as he has said, an “art practice.”

Anne Pasternak: How are you doing?

Virgil Abloh: Super good. Really good. How are you? Anne—I’m awesome. We’re opening Soul of a Nation next week, our major Black Power show that started at the Tate Modern, and I really want you to come see it. I think you’re going to love it. So, listen, shall we dive in? First of all, Virgil—wow. You’ve had a huge year, from becoming the artistic director of Vuitton’s menswear collection in March to being named one of Time magazine’s top 100 most influential people in the world. Not to mention, my favorite: designing on-court dresses for the queen of tennis, Serena Williams, for the US Open. Of all the millions of things that have happened just this year, what would you say, when you’re reflecting back on this period of your life, will be the most meaningful, happiest, joyous moment for you?

Virgil: You know, it’s weird. I’m thankfully not that into the accolades. They don’t do much for my internal metric of happiness. What does rate as important to me is the ability to get out ideas—that’s what’s exciting to me. I’m super happy that I have a platform, and I have access, and I have an ability to dream out loud in many different spaces. What I focus on a lot about this last year isn’t so much the highlights on paper. It’s more like the moments in between that get me to those highlights—the journey-versus-the-end-goal sort of mantra.

Anne: When you talk about having platforms, I cannot for the life of me think of another creative person who has as many so-called hyphens as you do: fashion designer, entrepreneur, architect, DJ, furniture designer, stylist, artist…the list goes on and on. Let’s start with thinking about platforms. How have you defied being put in a box?

Virgil: It’s my upbringing, in a way. I had an education and support that didn’t mandate [fitting] into any box, per se. It was like, ‘Hey, just do good at school and show up to soccer practice on time.’ I had parents from a third-world country, Ghana, and work ethic was the only thing that was mandatory.

I went to school and studied architecture, and whenever you study a field that is involved in the arts or art history, you’re starting at zero. The first thing you learn about is the origination of an architect, period—and the initial logic of an architect was, they did everything. It wasn’t that you just built buildings; you were supposed to be well versed in everything in order to make buildings, as a civic service to people. I took that to heart. Maybe I read the book the wrong way. I was like, ‘Oh, this is a license to be into hip-hop, skateboarding, soccer, and art, and not have to decide between them, but to work.’

Anne: So, the realization that architects design space for social experience was liberating for you and turned you on to the greater civic possibilities of design for everyone?

Virgil: Exactly. If you build something on the planet, it no longer just affects you. It affects everything around it. And that’s when I started applying the things I was learning to the world I was living in.

Anne: Among all of these hyphens, there’s been a great deal written about you in terms of fashion and your work as a designer. Did you ever imagine that you’d be in fashion? What led you to it?

Virgil: I didn’t imagine I would be in the center of it. I imagined I would be in whatever place was available on the outskirts. And that’s called ‘streetwear,’ and that’s what I was content with. Then I saw the opportunity, because the world was changing, to make a narrative with that through high fashion, which was sort of the pinnacle.

Anne: You read all the time that you’re being heralded for ‘bringing legitimacy to streetwear,’ and I cringe when I read that. I have to question: Legitimacy for whom? There’s a similar struggle over the paradigm of high versus low within the museum world, and I think it’s exclusionary and divides us along lines of race and class. I’m wondering if that statement that you’re bringing legitimacy to streetwear makes you cringe, as it does me.

Virgil: Well, it’s very much like the name Off-White, which makes you think along two polar opposites at the same time. That’s how I’ve been able to understand the world as it exists versus the world as it could be. That’s the balance that helps me think. So, yes, I think that statement is ludicrous, but at the same time I understand it. I understand that it’s a logic of how the world decides what should be on a runway and what shouldn’t.

At the same time, I’m an optimist, and I believe that I can be what it is I set my mind to. I’m not controlled by perception, because it’s not real. My work ethic is real, and that’s why I think I make as much stuff as I do. That can’t be erased. Logic, at a particular time, can.

Anne: It seems to me that really what you’re doing, not to bring up your engineering and architecture background, is being a bridge-builder. You’re creating space for this and that, and for them to coexist.

Virgil: Yeah. There’s an extremely low amount of dialogue that’s happening in the world today—or in the art system, or in fashion—about the boundaries that exist. I find a lot of fulfillment in connecting dots that I feel like might not otherwise intersect.

Anne: I know you’ve said in the past that discourse is missing from culture or from society. One of the reasons why I love being a museum director is that I witness daily how a museum supports discourse by bringing people together to learn and celebrate and question—and even debate and yell. I’m curious how that works when you’re working with a consumer brand. How do you create discourse?

Virgil: Well, I think brands are essentially another word for ‘tribes.’ People live with a product, and they understand the brand name and the brand value. The first source of inspiration about what project to make is how you can open up the logic of this brand to a customer base that might not otherwise know it, or restore the authenticity, or what the brand stands for, to a younger, millennial audience. I love how brands can communicate between the ‘tourists,’ who are casually interested and willing to understand, and the ‘purists,’ who are very precisely ‘anti.’

Anne: And what are you trying to communicate?

Virgil—That there’s a human behind a brand. That’s the story arc. It’s the Nike shoe that looks like somebody cut it up and wrote ‘Air’ on the side or drew on it. When I was younger, I didn’t believe there were humans behind these brands. I didn’t believe that I could ever get to a brand. Designers didn’t look like me. That was a huge thing that I had to work through, piece by piece. And that’s maybe why I enjoy working with varied brands. For me, brands are like people. It’s not a healthy person who has dialogue with just one person or with no one. I enjoy the dialogue and friendship.

“Fashion is only one prong to communicate during the time that we’re living in. Where I was coming from, it was the only device to get on a pedestal and have a voice loud enough to have an impact.”

Anne: Forgive me for saying so—you’re the pro on you—but I think you’re trying to say more than that. I don’t think it’s simply about, ‘Hey, kid, there are people designing these. There are people behind these brands.’ It seems to me you’re trying to shift the cultural dialogue. I go back to you as a bridge-builder—you’re bringing together urban, high fashion, wealthy elites and young kids, whether they’ve grown up in the suburbs or the projects. And they’re excited even when it’s something that they can’t afford or could only dream of attaining. There’s something in that bridging of these very distinct classes… I think there is a larger message to that.

Virgil: Well, the one thing I’m not—the one hyphen that you’ll never be able to put to my name—is a writer. I’ve dedicated my life to making. I’ll never be able to summarize it. And I think this goes hand in hand with this interview. How will this body of work be remembered? It’s possibly only through these interviews, when you come up with it. That’s the best pairing. I can’t decipher it.

Anne: I hear you. I’m married to an artist. I get it. But I’m going to go further with this for a minute. I think that your practice is one of great generosity and real inclusion. It’s a reminder that in a perfect society, we all exist side by side.

Virgil: True. That rings bells for me. I’m an optimist.

Anne: You once said to a group of young people, ‘My motivation is, in part, a bit of angst that comes from feeling like I don’t belong, that our generation doesn’t belong. I made a conscious decision that I wasn’t just going to be a consumer—that at least one of us would appear at the end of a Parisian runway.’ Do you still stand by that?

Virgil: One hundred percent. It sounds like my brain.

Anne: It’s a beautiful thing to say. Why does it matter to you that you are at the end of a Parisian runway?

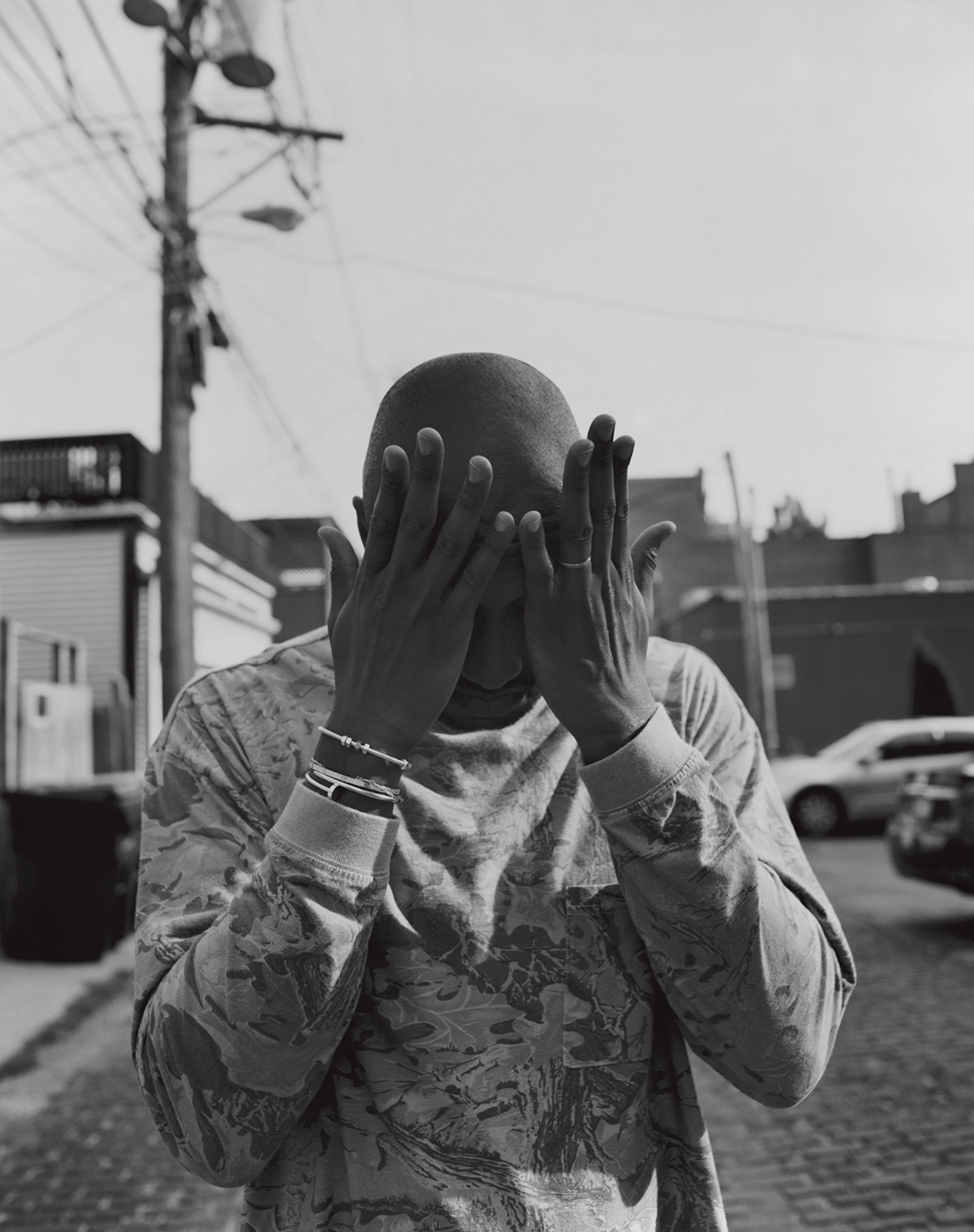

Virgil: Because I know that there’s a kid somewhere from off the beaten path that, like myself, didn’t believe it was possible—because he never saw it was possible. Seeing that image will make the conversation a lot shorter with a kid on the South Side of Chicago who’s trying to decide if he should sell drugs or go to fashion school. They’ve seen my narrative play out. This is my destiny. I was supposed to be here. Look at my body of work.

Anne: That reminds me a bit of one of the most powerful moments I ever had at the Brooklyn Museum, which was seeing the Kehinde Wiley exhibition. To see young people see themselves as they are—their ‘streetwear,’ their hoodies, and their low-riding jeans, all of that painted with such beauty and dignity—and watching them see themselves reflected in one of the most historic, oldest, biggest, most badass museums on the planet…

Virgil: Yeah, exactly.

Anne: It was really powerful. And when you’re the king of the Parisian runway, Virgil, I think you’re not only saying to young people, ‘You have this opportunity.’ You’re also saying that you’re seeing. ‘I see you. You’re here. Be here.’

Virgil: Yeah, exactly. That’s the message. And going back to what you were saying earlier—this can happen in a lifetime only through working. It doesn’t happen through posturing and thinking it’s possible. That’s what motivates me every day.

Anne: I know you love art. You’ve acknowledged Basquiat and Warhol as big influences. You’ve collaborated with Jeff Koons and Jenny Holzer, and you painted signs for Takashi Murakami’s show. You even said that your practice is not fashion, but an art practice. So let’s talk about this as an art practice.

Virgil: All of the different realms that I play in or make things in are simply, in my mind, part of a story arc that’s a much wider narrative. Fashion is only one prong to communicate during the time that we’re living in. Where I was coming from, it was the only device to get on a pedestal and have a voice loud enough to have an impact. For that young generation, it’s really how we communicate. The word ‘fashion,’ in my mind, is barely broad enough to describe the community of kids that hang out in front of Supreme every Thursday, that are part of that community. ‘Fashion’ also ties into music, art, and cultural boundaries. Under the hood of my logic isn’t a fashion logic. The end goal isn’t clothes. I’m not even that into clothes, to be honest. I’m more into what clothes mean to people.

Anne: In the so-called art world—

Virgil: —Capital ‘A’—

Anne: —It would be hard for you to fit in, because you defy categorization. You’re a painter, a photographer, and a fashion designer, but in fact, what you’re saying is that by talking about your work as an art practice, it actually liberates you to work in a much more creative universe. With that said, you’re going to have a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art [MCA] Chicago.

“I feel like we’re at a new Renaissance for young people, and it’s only if the presiding generation, the gatekeepers, adopt the new attitude that they will make that new Renaissance happen.”

Virgil: Yeah, in June 2019.

Anne: Very exciting. What would success look like to you for that exhibition?

Virgil: When you lift off all of the accolades, nothing hits my core more than the feeling of getting out ideas. Most people know who I am in the last three years. There was 12 years before that of all of these ideas, before anyone was paying attention or thought that I was any different than another black kid from Chicago. These ideas didn’t just come overnight. The exhibition will give a window into what I was thinking 15 years ago and the through lines of the ideas that I’ve been developing since then. It’s going to be a range of work, from fashion to art to music to photography—truly a multidisciplinary exhibition. The museum reached out to me three years ago.

Little did they know, from Louis Vuitton to Off-White showing small shows in Paris, what would ultimately be captured in the exhibition. Going back to your question of what success in that space looks like to me, it’s not being forgotten. So the work will be written about and documented, but most importantly, young kids who are fanatics of culture and coming to a museum maybe for the first time can look at work that they relate to and learn things that they didn’t know. That’s the success for me.

Anne: I was thinking, as you were describing it, about our David Bowie exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. I don’t think that there are that many people who have historically broken from those expected silos of the kind of practice David Bowie had—and certainly that you have. I find it really exhilarating.

Virgil: It’s the final frontier. I feel like we’re at a new Renaissance for young people, and it’s only if the presiding generation, the gatekeepers, adopt the new attitude that they will make that new Renaissance happen. If the gatekeepers of the art world keep those different silos around race, gender, equality, et cetera, we know what the world looks like. It shocks me that in creative spheres, there are people who are vehement not to let the natural evolution of art take place.

Michael Darling called me about the exhibition. With what he saw coming three years ago, he said, ‘There’s something at play.’ As the curator of an institution like MCA Chicago, he’s the one telling the stories. He was like, ‘I’m going to make a bet that the next Andy Warhol doesn’t look like Andy Warhol. He might look like you.’ That lets the gate open for a possibility that what may come in the future doesn’t look like what it did in the past.

Anne: What’s the next dream? Something that you haven’t done that you’re wanting to do at some point in your life?

Virgil: It’s tricky. Nowadays, if people ask me that and I say the answer in an interview, it might happen. Maybe I’d get a phone call. Then I’d be like, ‘Wait, this didn’t happen through hard work—it happened through clout.’ I consider that cheating. I don’t want to skip any levels. I want to work it out. There’s stuff I want to design that I haven’t designed yet. I’ll leave it at that.

Anne: I can’t wait. So what didn’t we talk about that you hoped we would talk about?

Virgil: You know, actually, we hit the nail on the head. You hit it with a reference to my main focus right now: As soon as the Louis Vuitton show was done, in an odd way, it became less of the dream, you know? Because it’s reality. So the dream now is that kids like me become the new artists; that there’s exhibitions three, four, five, ten years after mine by other individuals who weren’t ‘artists.’ And if you take the slider to our conversation, it’s when we talked about streetwear and legitimacy. We hit that, and it’s recorded in this conversation. Now it’s up to me to make more and more bodies of work and display them, in and out of museums, and in and out of galleries, so that one day, that doesn’t become a question. It looks like an ideology of the past.