Nicholas Weist visited Vince Aletti at his East Village apartment to dissect his immense collection of pop culture, fashion, fine art and gay pulp fiction.

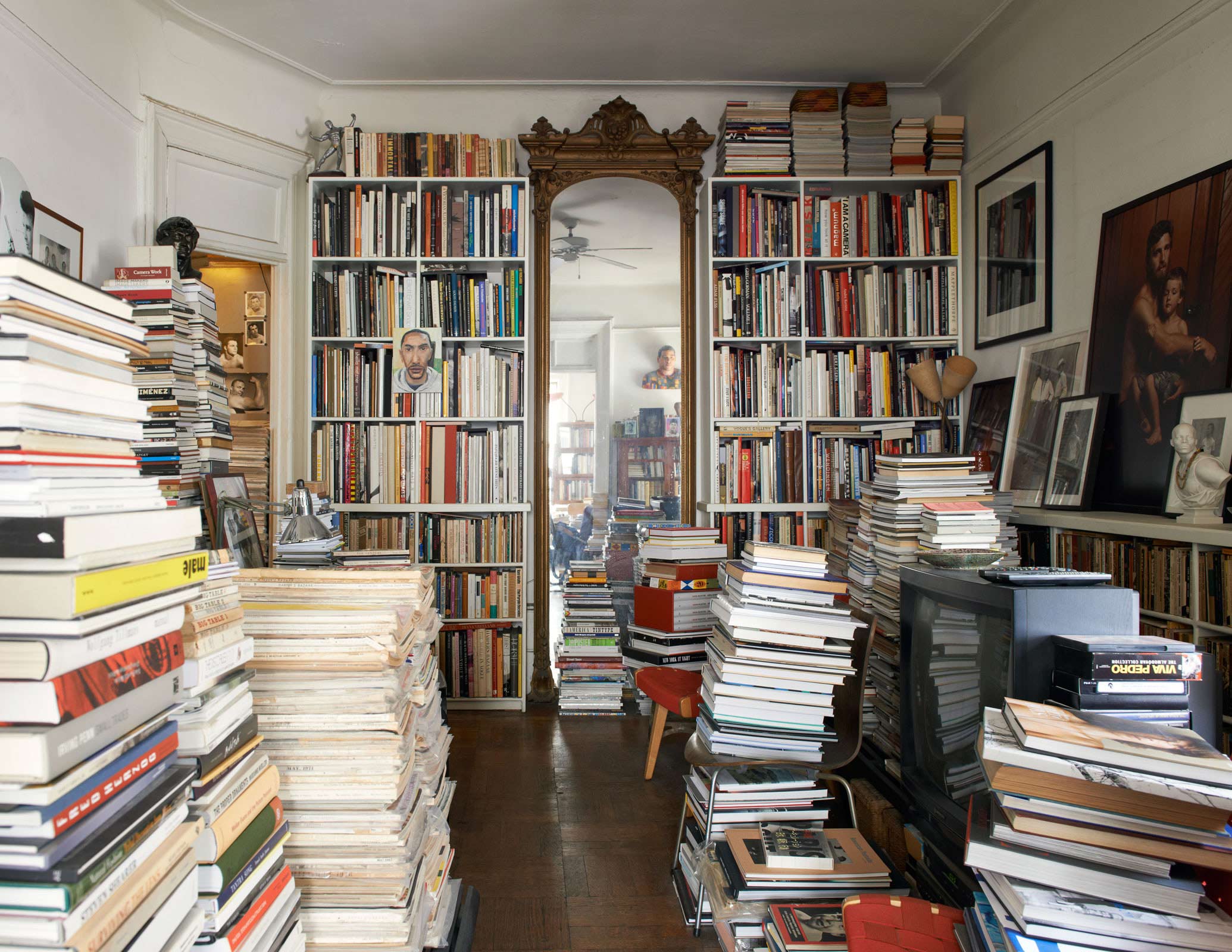

Vince Aletti’s East Village apartment is like a time capsule from the last three and a half decades. Seemingly endless stacks of neatly piled books and magazines fill the music and photography writer’s space. When organizations like the Metropolitan Museum of Art need to find old issues, they turn to Aletti’s vast collection, where they can find a mix of pop culture, fashion, fine art and gay pulp fiction. Nicholas Weist visited Aletti in his apartment to dissect his immense collection.

Nicholas Weist—So Vince, how did you start collecting?

Vince Aletti—Oh my god, how does anybody start accumulating things? I’ve done it all my life. As a kid, I had stamp collections. My interest was visual—the stamps had little pictures from all over the world. I remember also really relating to magazines as a kid, and subscribing to House & Garden. I didn’t know then that I was gay, but certainly it was a giveaway to everybody else.

I was interested in visual culture on different levels. My father was an amateur photographer and I grew up with a darkroom in the house. The mystery and romance of the darkroom is still potent for me. There were a lot of art books around the house, and my father had many “U.S. Camera Annuals.” They covered a populist idea of photography starting in the late ’30s—but it was edited by very smart people, and always included important photographers as well as camera club stuff. Often, as a kid, I looked for the nudes, but I also found incredible images that really stuck with me: Irving Penn and Richard Avedon and Bill Brandt…

Nicholas—When did you start collecting records?

Vince—I had 45s when I was a kid. I went to Antioch College, where one is constantly being shifted around for their work-study program—so you can’t accumulate much. It forced me to pare down what I was holding onto, but there were certain records that I always traveled with, and certain books and things.

Nicholas—You eventually donated your entire record collection to the Experience Music Project Museum in Seattle. Was it hard to let go?

Vince—No. Well, yes and no. Two friends, former editors at the Village Voice, had become curators at EMP. They told me that they had a great archive and an archivist who really took care of the material. I wanted to donate the collection to an organization that could keep it together and have a sense of its value as a collection. I spent a lot of time making sure everything I gave them was important. But I do regret it on some level, because all that music is still in my head, and most of it is not on CD, or available in quite the same way. Anyway, I desperately needed the space that all the records took up.

Nicholas—When did you move into this apartment?

Vince—[Laughs] 1976. Before this I lived two blocks away, on Avenue A and 12th Street. I was there for maybe 15 years.

Nicholas—I hope you’re rent-stabilized.

Vince—Yes, ha.

Nicholas—Has your library here been archived as well?

Vince—No, not at all. That’s become a bit of a problem, actually! When I’m looking for a certain book, it might take me days to find it. I need to be better organized, but that would take a whole year in itself. At least it’s orderly.

Nicholas—Is there one thing that you’ve been looking for lately and have had trouble finding?

Vince—I know I must have a copy of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” somewhere. I have a really large library of novels that I intend to read. I’ll think of a book I should read, and pull it out to put by my bed. But often that’s where it remains. Looking for a particular issue of a magazine, usually because someone asked me about it, can be a problem, unless it’s an American Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, which are very organized here by year.

Nicholas—Do you have plans for the magazines to end up somewhere, like your records?

Vince—I’ve been talking with different people who are interested in placing them with institutions, because most libraries that care about this kind of material have already been collecting it! Although in some cases they only have bound volumes. When the Costume Institute at the Met did that “Model As Muse” show, they borrowed some things from me because they wanted to have individual issues on display.

Nicholas—Is there a particular issue of something that is particularly meaningful for you?

Vince—Here’s an April 1965 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. This is a very rare one because it has a blinking, lenticular eye on the cover. Most of the copies I’ve seen don’t have the eye. This is from the middle of my college years when I was completely into pop culture. It was Richard Avedon’s 20th anniversary at Harper’s Bazaar, and he did every single picture in the issue—he basically designed it as well. Inside, he’s photographed Paul McCartney, Henry Geldzahler, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Jones, Bob Dylan, Roy Lichtenstein. They were all young at this point.

This magazine represents a major, major moment for me—really great design, interesting range of pictures and ideas. I remember obsessing about it and cutting it up to put pieces of it on the wall of my dorm room. I took it around to every apartment I lived in after that. Avedon was celebrating this moment in culture in a broad way, and included fashion and art. [Flipping pages.] Here’s Ringo. Here’s Lew Alcindor—later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar—as a teenager. I’m completely obsessed with this image. Here’s the club scene in London. For me, this is the equivalent of a great Avedon book. That’s one of the reasons why I love magazines. I think a great magazine has the quality and integrity of a great book. It’s more ephemeral, but it’s also more of that moment. There are no excuses—it doesn’t need to be an impressive feat of publication, it just needs to reflect what’s going on.

Nicholas—Are there magazines you miss, that ended publication?

Vince—Oh, plenty. The Face, for instance. That’s one that I wish I had every issue of. It had great art direction, really good photos. The Face would jump on a new performer and put them on the cover when you hadn’t even heard of them yet. And usually they were right. There’s a really interesting magazine from the ’30s called The Bachelor. It looks like Vanity Fair or Town and Country, but it’s clearly gay. It didn’t cover gay subjects per se, but almost all the people in it are gay. There are Paul Cadmus covers, George Platt Lynes photography. There’s another men’s fashion magazine called Gentry that I also really like. It lasted for about four years in the ’50s and was focused on men’s fashion but had articles about hunting and fishing and golf, and covers by Henri Matisse and pullouts of Japanese calligraphy and Chinese vases.

“I think a great magazine has the quality and integrity of a great book. It’s more ephemeral, but it’s also more of that moment. There are no excuses—it doesn’t need to be an impressive feat of publication, it just needs to reflect what’s going on.”

Nicholas—When you add to your collection, do you feel the need to acquire things right when you see them, or do they drift into your consciousness through happenstance?

Vince—Often I feel like if I don’t buy something right away, then I’ll never buy it. Especially with magazines—if I see a magazine on a newsstand and kind of look through it and think, Oh, I don’t know, I almost never go back to buy it. But books are different. There are times when I want to go back to see a book twice before buying it, the same way I need to see a show twice before I get it.

Nicholas—Your collections—magazines, books, photographs—they are very democratic. Pop culture, high art, gay pulp all collide.

Vince—Yes, it’s a reflection of my taste, with some sense that it’s corrective to other things that are out there, but not in an academic way.

Nicholas—But also not in a dilettantish way.

Vince—Every picture has some kind of meaning for me. In my photography collection it’s important for me to represent my image of male—which is multicultural and historic in a broad range. I’m not focused on masterpieces. It’s important to me that a lot of unknown authors and subjects are represented. That’s part of how my book “Male” came together.

Nicholas—Did the show at White Columns come first, or the book?

Vince—The show happened first. Matthew Higgs, the curator of White Columns, came to my place to borrow some albums—he was doing a show on liner notes. When he was here, he got really interested in what was on the walls and asked me if I might be interested in doing a show. Working with Matthew was especially fun for me because he’s such a music nerd, especially about disco. He ended up organizing this publication of all my disco columns, Xeroxed and bound in a three-ring binder. We launched the binder at the closing of the “Male” show.

Nicholas—And is that what became the book “The Disco Files”?

Vince—Exactly. The publisher, DJhistory.com, researched the material, found all the things that I didn’t have copies of and made a real book out of it.

Nicholas—Do you keep the copies of the books you’ve written in a special place?

Vince—I should. I only have, like, two copies of “The Disco Files,” which is kind of crazy!

Nicholas—I have multiple copies of the books I’ve made, and every time I see them in cold storage I think, Why do I keep these?

Vince—I do too, about some of my books. I think, Yeah, I want to have them, but who really cares about this stuff anyway? [Laughs]

Nicholas—What would you grab if you had to leave for good and could only take what you could carry?

Vince—This picture and this handprint, both Gary Schneider, and both of Eddie Delgado, who died two years ago. I met Eddie at Paradise Garage and he became a really important part of my life.

I would also take this portrait of a shirtless young guy who was a boyfriend of mine at the time, named Manny. I asked Peter Hujar to photograph him, and Peter got some really wonderful pictures of him from that one session. I miss Peter in a lot of ways, one of which is missing him as someone who could photograph a friend and have that picture really mean something. I change the pictures in my apartment a lot, but this one has always been there, in that same space high on the wall. But all of these pictures mean something to me.

Nicholas—How did you meet Hujar?

Vince—Through a guy named Jim Fouratt. There were a few interesting characters at record companies who were hired because the company had no real understanding of the music they were putting out—Jim was one of those people. He was the company freak at Columbia Records. He was also very involved in gay rights and at the time, and he become famous for his involvement in gay liberation. I briefly worked for Columbia Records in their publicity department, and got to know Jim. While he and I were hanging out, he and Peter Hujar became boyfriends. When they broke up, I remained closer to Peter, and was really close to him until his death. He actually, for a long time, lived directly across the street from me.

Peter taught me a lot more by example than by talking. He taught me so much about how to look at pictures and what to think about when you’re looking at pictures. I can’t really remember going to shows with him, but he and I would sit and look at magazines, especially fashion magazines. He was a very interesting critic of all of that, about what worked and what didn’t. Also, knowing a working photographer, someone whose life was photography and who had difficulty making it work for himself, helped me to think about the person who makes the work we see on a wall. It doesn’t just come from some place in their head—rather, it’s a lifetime of involvement.

When I started writing about photography, one of the first ways I approached it was to write profiles of photographers—to write what I thought of as critical profiles. Mostly of people who were just starting out, partly because I was intimidated to write about someone who had a long history of photography, but mostly because there were young people I was very curious about.

“Men are a mystery, and that’s part of what’s exciting and attractive. The pictures are a way of having a larger sense of how men present themselves.”

Nicholas—Do you remember a couple of those people?

Vince—Oh sure! Dawoud Bey, Barbara Ess, Sally Mann, Neil Winokur …

Nicholas—Then this would be late ’80s, early ’90s?

Vince—Yeah, late ’80s. I always liked to find out the story behind the photographer, and also to realize how articulate most of the photographers were. Maybe I was just lucky, but almost everyone I talked to was very eloquent about their work, and not in an academic way. They didn’t have any sort of lingo; they were just passionate and real.

Nicholas—Do you have a personal connection with any of the other artists you collect?

Vince—There are some photographers that I’m really friendly with—Gary Schneider, Bill Jacobson. But there are a lot of people I don’t know and whom I don’t want to get to know too well, because I feel like I need to maintain a certain distance.

Nicholas—It’s difficult for a critic to be close with an artist, I’d imagine.

Vince—It’s a fine line. I think once you get to know somebody, especially if they’re nice—and most often they are—but even if they’re not nice and you don’t want to get to know them at all, it’s a difficult situation. You just need to be able to step back. Not from what their intent is, because that’s important to understanding their work, but in order to not get caught up in their personality.

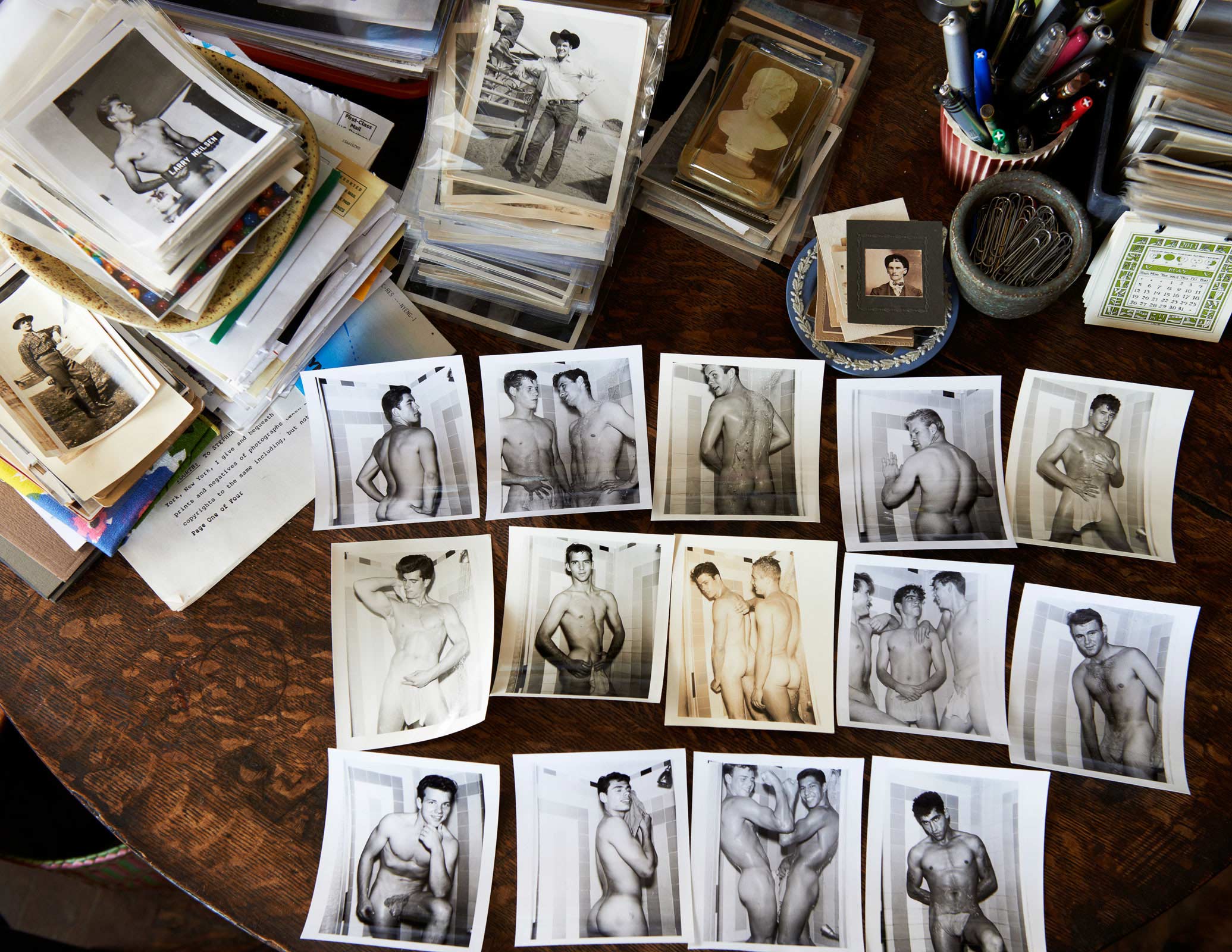

Nicholas—You also collect pictures by beefcake photographers like Bob Mizer.

Vince—In fact, I just published a book with Acne about my collection of Bruce of Los Angeles’ photographs of cowboys. He traveled to rodeos all around the country in his spare time. I like that these pictures aren’t well-known. Also they’re real guys, although clearly the whole cowboy thing was part of a fetish of masculinity. The cowboy, the construction worker, the motorcycle guy …

At some point I would love to do a book of these shower pictures from the Athletic Model Guild, which was run by Bob Mizer. Mizer was the most eccentric and long-lasting, most witty of all the physique photographers. When you look at a lot of his work, you see that he had a basic series of things he would do with models—some poses, some places, some backdrops—and at some point, I assume at the end of the session, they would end up in the shower. The shower itself—I’ve seen pictures of it—is actually a very small, narrow space, but it’s nicely tiled. And the pictures are all taken essentially from the same angle and distance. I have a feeling that the camera or maybe a tripod was just there, already set up. So we are looking into the same space, from the same angle, at a whole population of guys who came though over the years. These seem to be mostly from the 1960s.

Nicholas—It’s curious that although your collection is very focused on male portraiture, it’s also divorced from a particular sexuality.

Vince—I’m not concerned with whether the artist is straight or gay. That has nothing to do with how I receive the work. I think of Larry Clark as a good example—like, where is he? He had a gay take on guys maybe, but he’s not gay. I also have a lot of anonymous work. Like this. This guy with the hat, which is also in the “Male” book. I don’t know anything about this image—it even came in that frame.

Nicholas—Do you think about the narrative of the subject?

Vince—Sometimes. For instance, this picture of two soldiers in the snow. I think the setting is beautiful, but are they soldiers? What are they doing there? The format of so many of these, the detail, the way they’re framed and designed, is fascinating. Here’s two cowboys. Actually I’m not sure if he’s a cowboy or just some kind of—

Nicholas—an ecologically-inclined dandy.

Vince—Yeah. His boots are pretty gay.

Nicholas—His tie is outrageous.

Vince—I did a show at ICP called “This Is Not a Fashion Photograph.” I often look at pictures that are not fashion photographs, but really, they are great fashion pictures.

Nicholas—And maybe the photographs can tell you about their own periodicity.

Vince—Exactly. And suggest details of people’s lives. It can be really moving.

Nicholas—Have you drawn any conclusions about maleness, or the imaging of men?

Vince—No. I don’t think about those ideas to draw conclusions, but to open them up and to keep them open. When I have thought about them, and when I’ve written about them, it’s more about the variety of ways men are presented and have been presented historically, and how that’s changed. But how so much has remained! I mean, this picture of a smiling boy could have been taken last year. There’s something very contemporary about the best pictures—they transcend time. But I also always think about how I don’t really understand men. Men are a mystery, and that’s part of what’s exciting and attractive. The pictures are a way of having a larger sense of how men present themselves.

Nicholas—Alright, I’ve thought of my crowning question.

Vince—Okay. Crowning!

Nicholas—This is the absolute big one. So we talked about Avedon’s portrait of Lew Alcindor. You cut that picture out and put it on your wall. Even though you already had a copy of the image, have you ever wanted to buy a print?

Vince—I wish I could have afforded one! But I had the picture, and now I have the magazine—actually I have many copies of the magazine. When I first started collecting the Bazaars and Vogues, it was really because of Penn and Avedon. Even though I have never been able to afford their prints, I have an amazing collection of both of them—and Horst and Beaton and Helmut Newton and all those people.

Nicholas—And if you had a million dollars …

Vince—[Laughs] Oh my god, well there’s too much, too much! Probably I would want to buy a real print of the Lew Alcindor picture. It’d be wonderful to have that. But that would be such a hard decision. There’s just too much! Avedon’s prices are such that I could buy 10 other things—and I probably would choose to buy those 10 other things. If I did have that money, I would probably divide it as many ways as I could.

This conversation first appeared in Document Fall/Winter 2013 issue.