Artist Robert Longo and designer Rick Owens discuss throwing a punch, identity and longevity in art.

In the late 70s, Robert Longo lived in New York City in a loft with fellow artist Cindy Sherman. Too broke for SoHo, the couple holed up on South Street, and, over the next few years, developed a community that created works that came to define the cultural and critical dialogue of the city in the 80s. Along with the likes of Richard Prince, Troy Brauntach, Jack Goldstein, Barbara Kruger, and others, Longo and Sherman—lovers then friends—made pieces of media-sensitive, politically shrewd performance, photography, film, video, and drawing that shot to the heart of an increasingly consumeristic, image-laden society. Longo, in particular, began a dialogue that was at once ambitious (literally: his pieces were massive in size) and intimate, tackling subjects like nuclear explosions, giant waves, and animals in cages through painstakingly produced charcoal illustrations. From the iconic 1980-81 “Men in the Cities” series, which portrayed men in suits, languidly falling through space in images entrenched in the language of advertisement with fatalistic undertones, to Longo’s frozen montage “Combine” works from 1982–88 (massive, politically charged, mixed-media painting, drawing, and sculptures), to 1989’s dark “Black Flags” pieces and 2002’s “Freud Cycle” drawings, the artist has addressed what it means to work against the weight of the world in dauntingly nuanced terms. This fall, Longo has not one but three major exhibitions—“Proof: Francisco Goya, Sergei Eisenstein, Robert Longo,” which he helped curate, at The Brooklyn Museum, a solo exhibition at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London, and a second solo exhibition at Finland’s Sara Hildén Art Museum.

Above The Fold

Sam Contis Studies Male Seclusion

Slava Mogutin: “I Transgress, Therefore I Am”

The Present Past: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Pierre Bergé Has Died At 86

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

An Olfactory Memory Inspires Jason Wu’s First Fragrance

Brave New Wonders: A Preview of the Inaugural Edition of “Close”

Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part One

Modelogue: Georgia Hilmer’s Fashion Month, Part Two

Surf League by Thom Browne

Nick Hornby: Grand Narratives and Little Anecdotes

The New Helmut

Designer Turned Artist Jean-Charles de Castelbajac is the Pope of Pop

Splendid Reverie: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Fall/Winter 2017

Tom Burr Cultivates Space at Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Tire Building

Ludovic de Saint Sernin Debuts Eponymous Collection in Paris

Peaceful Sedition: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Ephemeral Relief: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Olivier Saillard Challenges the Concept of a Museum

“Not Yours”: A New Film by Document and Diane Russo

Introducing: Kozaburo, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Marine Serre, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Conscious Skin

Escapism Revived: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Spring/Summer 2018

Introducing: Cecilie Bahnsen, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Ambush, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

New Artifacts

Introducing: Nabil Nayal, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Bringing the House Down

Introducing: Molly Goddard, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Atlein, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

Introducing: Jahnkoy, 2017 LVMH Prize Finalist

LVMH’s Final Eight

Escaping Reality: A Tour Through the 57th Venice Biennale with Patrik Ervell

Adorned and Subverted: Backstage MB Fashion Week Tbilisi Autumn/Winter 2017

The Geometry of Sound

Klaus Biesenbach Uncovers Papo Colo’s Artistic Legacy in Puerto Rico’s Rainforest

Westward Bound: Backstage Dior Resort 2018

Artist Francesco Vezzoli Uncovers the Radical Images of Lisetta Carmi with MoMA’s Roxana Marcoci

A Weekend in Berlin

Centered Rhyme by Elaine Lustig Cohen and Hermès

How to Proceed: “fashion after Fashion”

Robin Broadbent’s Inanimate Portraits

“Speak Easy”

Revelations of Truth

Re-Realizing the American Dream

Tomihiro Kono’s Hair Sculpting Process

The Art of Craft in the 21st Century

Strength and Rebellion: Backstage Seoul Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Decorative Growth

The Faces of London

Document Turns Five

Synthesized Chaos: “Scholomance” by Nico Vascellari

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

New Perspectives on an American Classic

Realized Attraction: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Dematerialization: “Escape Attempts” at Shulamit Nazarian

“XOXO” by Jesse Mockrin

Brilliant Light: Backstage London Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

The Form Challenged: Backstage New York Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Inspiration & Progress

Paskal’s Theory of Design

On the Road

In Taiwan, American Designer Daniel DuGoff Finds Revelation

The Kit To Fixing Fashion

The Game Has Changed: Backstage New York Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

Forma Originale: Burberry Previews February 2017

“Theoria”

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

In Florence, History Returns Onstage

An Island Aesthetic: Loewe Travels to Ibiza

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

A Return To Form: Backstage New York Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Offline in Cuba

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Archetypes Redefined: Backstage London Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

A Week of Icons: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Spring/Summer 2018

Toasting the New Edition of Document

Embodying Rick Owens

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

Fallen From Grace, An Exclusive Look at Item Idem’s “NUII”

Breaking the System: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

A Modern Manufactory at Mykita Studio

A Wanted Gleam: Backstage Milan Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

Fashion’s Next, Cottweiler and Gabriela Hearst Take International Woolmark Prize

Beauty in Disorder: Backstage London Fashion Week Men’s Autumn/Winter 2017

“Dior by Mats Gustafson”

Prada’s Power

George Michael’s Epochal Supermodel Lip Sync

The Search for the Spirit of Miss General Idea

A Trace of the Real

Wear and Sniff

Underwater, Doug Aitken Returns to the Real

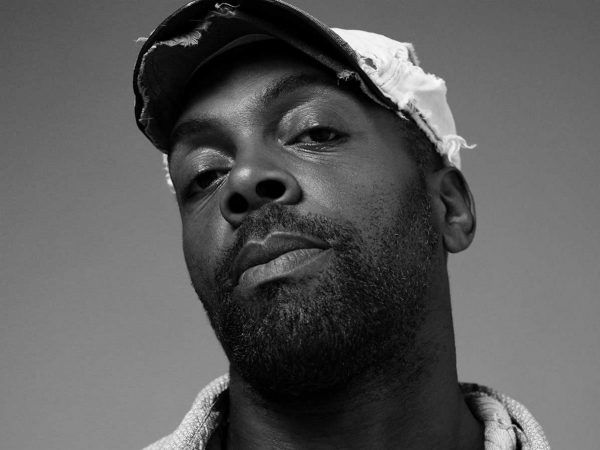

Rick Owens first met Longo at a dinner party in Paris. The designer, uninhibited, hedonistic, and ever-committed to a house and aesthetic that extends far beyond brand and into the realm of cult, instantly bonded with the outspoken artist and his wife Barbara Sukowa. This summer, the fashion designer phoned the artist from his home in Venice to talk about what it means to maintain moral integrity in the arts, the allure of throwing a punch, and the perils of creative longevity.

Rick Owens—We met in Paris. I remember, I was at a dinner and was sitting next to your beautiful wife Barbara at Maxim’s, one of my favorite places in the world.

Robert Longo—You gave her the most spectacular dress for when she got the award for best actress at the Venice Biennale. She looked like a warrior princess compared to everyone else. And then I went to see that spectacular fashion show that was in that stadium.

Rick—Which one was that? They are all a blur.

Robert—It was a weird version of an almost schizophrenic combination of like “Triumph of the Will” and a monster truck rally. It was in the stadium and the lights were incredible and the music was fucking amazing. This onslaught of models just kept coming. It was almost like the scene in “Fantasia,” with the brooms coming at you, when Mickey lost control. I was so jealous when I saw it—it was such a great performance piece.

Rick—They are fun to do. It has to be theatrical, it has to be fast, and there is a big element of risk, because it’s not like you have really rehearsed that much. It’s really kind of like throwing yourself into a mosh pit.

Robert—It felt relentless. It is really interesting with art—there’s art you see, then there’s the art you remember. What was interesting about that fashion show was that it happened so intensely that the image was burned into my mind. That show is definitely a performance art piece. Actually, the best performance art piece I have seen in a long time.

Rick—Well, it’s kind of like coming together to celebrate a climax of glory, isn’t it? There’s been controversy about fashion shows, and I think it’s impossible for them to be dead. It’s just another kind of way for people to collect together to experience something climactic. That will never die. It will be a fashion show, a rock concert, an art show, an art performance. You just can’t eliminate that.

Robert—It transcends the idea of it being about fashion. It is not simply about clothing.

“You want to believe that the world could be a better place somehow. Artists are indicators of time, we’re reporters of what we live in.”—Robert Longo

Rick—Fashion is communication—that will always happen. What I love most about your work is that it has a moral code, and I think that’s missing in art a lot. A lot of what I see is so much about irony or maybe wit. I love wit, but I think that your stuff is more profound because it deals with how you feel about morality. I sense that is important to you when you are putting stuff out there. Am I right?

Robert—Oh, it’s absolutely right. I mean the terminology “moral code”—I wish I thought that up. What is really important for me in the creative act is this idea of how do I make sure I marry a degree of humanity and justice within the work? From the very beginning—because I emerged during the time of Reagan—so much of the work has to do with rage and frustration and wanting to rip chunks of the culture out and put them in your face and say, “Look at this, make a decision, take a position.” I think it is very important you confront viewers, you don’t give them this banality, you give them a challenge. The way people respond to my work is always pretty strong one way or the other. The moral code is definitely a part of it. You want to believe that the world could be a better place somehow. Artists are indicators of time, we’re reporters of what we live in. I am basically trying to show what we are dealing with. At the same time, I am trying very hard to slow down this incredible onslaught of images that we deal with on a daily basis through this really archaic medium of drawing with charcoal. Did you ever see that movie by [Werner] Herzog? He made this movie [“Cave of Forgotten Dreams”] about cave drawings. These drawings were spectacular; they are 30,000 years old. After watching I thought, “That’s my ancestry.” I make charcoal drawings, images out of burnt dust. They are incredibly fragile, and, at the same time, really aggressive.

Rick—I hadn’t thought about that connection: How primal your work is because you are working with burnt sticks.

Robert—It is such a fragile medium. It is dust crushed into paper, it’s not like paint, which is a surface—this is actually embedded into the paper. I like the fact that I make drawings that are so big. Some of the drawings weigh almost a ton, which is in itself ironic to me. Drawing is always a peculiar, intimate kind of bastard of the high arts. There is painting, sculpture, and then there’s drawing, which is always usually in those badly lit, brown rooms in the basement of museums. I took a medium and really exploited it, for sure.

Rick—I always liked drawings because of that fragility, but also because of the spontaneity. Usually when I am looking for sketches for bigger works, it is a kind of more pure idea before it turns into something big and architectural.

Robert—Oh, it is definitely the root of everything. You are dealing with [the idea] on a molecular level. It is so primal. I like that it is very labor-intensive. There is so much right now where you can just press a button to get things done. To me, the idea of making a drawing requires a kind of commitment. In a weird way, a commitment to a singular image is more radical than anything else I can think of. The technique is pretty wacky. We have to wear masks and there are a lot of air purifiers in the studio. I always worry

I am going to get black lung disease or something.

Rick—I think I heard you talk about how it was your religion once—that there is this spiritual quality to really being present to an idea and immersing yourself in it.

Robert—Art is a religion. I like the idea that I don’t know of any people that have been killed in the name of art. It is so much about believing in something. I love art history, I love old art. There is nothing like going into the museum and seeing great paintings by Rembrandt or Caravaggio. I still get a rush from that stuff.

Rick—I was reading about the upcoming show you’re doing with [Francisco] Goya and [Sergei] Eisenstein, I had never seen Eisenstein’s work, so I’ve been watching his films on YouTube. I watch black-and-white movies on a big screen every day while I’m showering and doing stuff around the house. That imagery reminds me of you, and I felt like I recognized a lot of myself in it too.

Robert—The compositional framing of this stuff is amazing. You have to realize that Eisenstein is the guy that gave us this theory of montage. Before he came along, people really didn’t quite understand this idea of a cut. When the curator Kate Fowle came to me and said that she wanted to do this exhibition with Goya, Eisenstein, and me, my initial reaction was, “What do I do in the show?” It was quite humbling to be put in context with these two giants. She brought me into this conversation with curating it and one thing we came up with was that we all worked in black and white. We got Goya’s etchings and made a very specific edit. Eisenstein’s films were tools of oppression and propaganda, so we stripped out all the sound and all the subtext, and then I slowed them down to about 1 percent. The idea was of these artists responding to the time they were living in. Not necessarily making documentary ideas, more just a visceral response to things. There is a continuity to it all.

Rick—You say that you feel humble, but it sounds completely logical to me, the three of you. It is so beautifully balanced.

“When I die I want to have bitten off everything I could chew. I want as many scars as possible, I want to enjoy everything.”—Rick Owens

Robert—I am doing a show in London in September. I took the title from Macbeth. When everyone complains about how fucked up everything is, he basically says, “Let everything fall apart, and then let’s rebuild it.” That’s the kind of attitude I’ve had lately.

Rick—That’s what I think is actually gonna be the good part about Trump. He’s going to make all of us react. That could be the healthiest possible thing. Maybe it’s all going to work out for the best [Laughing.]

Robert—I always wonder if I was younger if I would join up with these anti-fascist people.

Rick—I think that if I were younger, I think having an excuse to fight would have fueled me.

Robert—My middle son, who’s an incredible rock musician, decided to get really seriously involved in mixed martial arts. We go to boxing matches together all the time. Fighting was a real big part of my life for sure.

Rick—Mine too. But I think I was less successful at it. Actually I am sure I was.

Robert—It doesn’t matter. There’s three things when words are never enough: fighting, fucking, and making art. When words just don’t work anymore that’s why we do those things. I am sure there’s people that say a lot of words when they’re fucking but…

Rick—Michelle and I spend a lot of time apart and sometimes it’s a little awkward acclimating ourselves to living together again. Do you have that?

Robert—Absolutely. Barbara is back from filming and out in Fire Island, and I hope to join her soon. I’m here in the studio, which is pretty crazy right now. It’s a long-distance run.

Rick—Exactly! How long have you been together?

Robert—Over 24 years.

Rick—Yeah, I’ve been with Michelle for 25 years. It is definitely a long-running thing.

Robert—The idea of long distance is very interesting when you deal with young artists. They want to know the key to becoming successful. You want to explain that being an artist is a long-distance run, we are not professional athletes, we don’t have this window where we have to become successful before we’re 30. This distortion is in New York more than anyplace else. I was part of the generation that was really lucky. Cindy Sherman and I lived in New York together and when we moved there, there were maybe five important galleries and a couple hundred artists that I knew, but making money wasn’t necessarily on the menu. We were hoping to make our art and support ourselves. I drove a taxi. She worked at the department store A & S. Now I wouldn’t want to be a young artist at all…I would be crazy. It must be similar for you as a designer.

Rick—I wonder if young people have a different sense of entitlement than other generations. I was planning on being poor forever, so I don’t know. I never had a bunch of ambition or high goals. This generation with access to so many success stories on the internet, I think people think they can do that.

Robert—I am incredibly impatient in general, but that’s because I am a compulsive, excessive person. I realize it takes time to do things—it’s obvious in the way I work. I have three sons and watching them navigate their lives is always difficult. Thank god I don’t have any more kids, they would be pretty wacky. Now I have cats.

“There’s three things when words are never enough: fighting, fucking, and making art.”—Robert Longo

Rick—Yeah, I missed the opportunity to have kids. I think I would’ve been kind of an intense father. I really would’ve hovered. Were you okay with that?

Robert—Sometimes kids are highly overrated, but that’s a different story. My father was abusive and missing, so I tried to be the father I wish I had. I did a lot of stuff with my kids and I gave up on a lot of things in the world. I coached their basketball teams and baseball teams, and I don’t regret it at all. I had some really great joy with them. What’s really weird about kids is when they are really little, they are absolutely extraordinary. If you do everything right, they should become ordinary when they become teenagers. They become incredibly abstract, and you don’t even know who the fuck they are anymore—it’s like some weird science fiction film, like who is this fucking monster living in my house?

Rick—Yeah I would never have had the patience with kids. I guess it’s different when they are your kids.

Robert—Yeah, but I also had the wife with the kids, which was a very important thing. I did miss a lot. My life was quite animated in the 80s. When the kids came along, things changed.

Rick—Did you overdo it in the 80s?

Robert—I’ve been sober for almost 20 years. I guess that explains it a little bit. I had enough success that I basically tried to use all the money I was making to make my work and the work got bigger and more complicated. I was out of control. I didn’t have a role model for how I was supposed to be as an artist. I wanted to be a rockstar artist. Drugs at one point seemed like a way of fueling myself, coke gave you all this incredible energy to act, but then you start dabbling in all this other shit like heroin, you start getting really lost with this shit. I went to this rehab in Arizona and it saved my life. I sometimes miss a glass of wine, but there was a really rough period of time when I didn’t know how to find what it was I was doing when I first got sober. I find now I can go to the same places I went to in my mind when I would get fucked up, but now I am much more judicious in my thinking and more careful in how to execute things. I am still pretty compulsive, but I am not out of control. How about you?

Rick—I think I want Robert Longo to have been a monster rockstar out-of-control artist in the 80s. That’s what I want to know. I hope you don’t regret it.

Robert—No I don’t, I can’t. It happened, it’s okay. When people start criticizing the money in the art world, they go back to me and Julian Schnabel. We had the original stain. Meanwhile, people like [Jeff] Koons have made money that makes what we made look like cigarette money. We are the original sinners. But that’s okay. I always think of the idea of artists making money, and people frowning upon it, like, “What, you still want us to be starving and cut off our fucking ears? What do you want?”

Rick—I think you deserve all of it, and more.

Robert—Thank you Rick, thank you very much.

Rick—I went through all the excesses and everything and I love it. I wish I could still do it and still have that appetite and I could bounce back from it. I just can’t handle it anymore so I just don’t do it. When I die I want to have bitten off everything I could chew. I want as many scars as possible, I want to enjoy everything. I am a big believer in indulging appetite.

Robert—I agree. You want to burn bright but you want to burn long.

Rick—Yeah, luckily we were able to get our time in and can figure out how far we can go. A lot of people aren’t that lucky.

Robert—I think we’re making the best work of our lives. We are smart enough, we are old enough, we have some knowledge now. I look back at my own career and there were times I really lost myself, but I think right now I am really rocking. My focus is really intense. I go to sleep at night wanting the night to go really fast so I can get up in the morning. I am that ready to fucking go. It’s that exciting to me. I always worried what it would be like to be at this age, do you just give up? Or forget? What happens? What’s that line from Robert Frost? “Miles to go before I sleep?” I got my running shoes on.