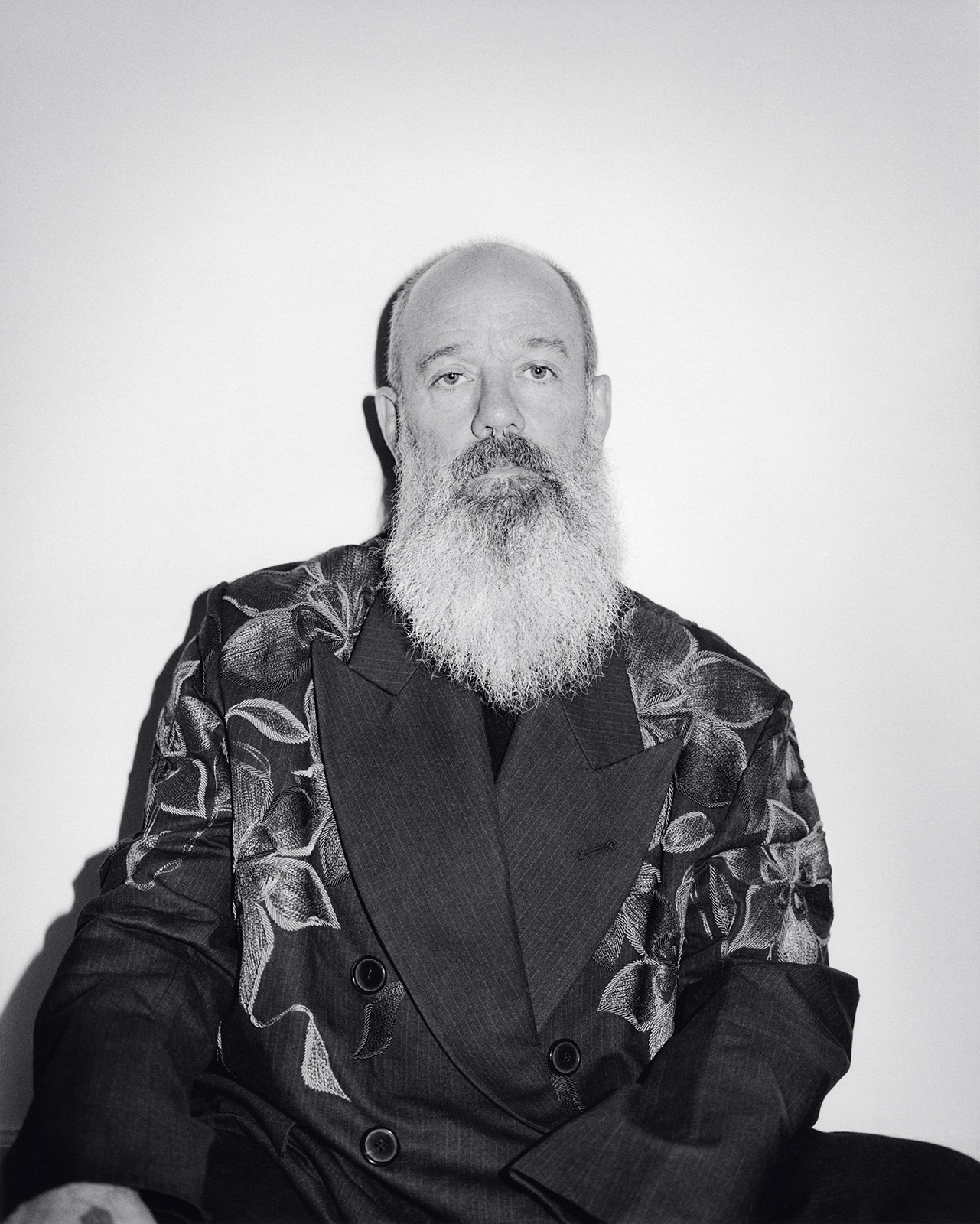

At Stipe’s Chinatown apartment, the pair talk party music, late-stage capitalism, and social media-induced narcissism for Document's Fall/Winter 2017 issue.

When Warren Fischer and Casey Spooner formed the electroclash duo Fischerspooner in 1998, they set out to open minds and expose the masses to worlds of art and performance through synth-heavy dance music. They identified not as a band but as an art collective, introducing themselves to the New York scene with an outsized, glitter-doused glam performance at an East Village Starbucks. Through a hedonistic mesh of new wave and retro electropop, they sought to dismantle the way that people experienced electronic music with animalistic exuberance. They succeeded with their 2001 album “#1,” releasing tracks like “The 15th” and “Emerge,” which became ubiquitous on dancefloors across the globe. Their unbridled flamboyance eventually landed them a spot performing on “Top of the Pops,” a British show consumed by the mainstream.

Spooner met Michael Stipe almost a decade after the artist had formed the pioneering alternative rock band R.E.M. and just before he would release the Grammy-winning single “Losing My Religion,” followed by hits like the somber “Everybody Hurts” and the tribute to comedian Andy Kaufman, “Man on the Moon.” Spooner was a college freshman at the time (more into Grace Jones than R.E.M. in all honesty) and Stipe, a decade older, soon became his first boyfriend. The two have been friends for some three decades now.

They became official collaborators when Stipe stopped by Fischerspooner’s downtown studio in 2014, when the duo was stuck on the last track of their upcoming album. Stipe advised the pair on how to fine-tune it, eventually becoming a producer for the entire body of work. The result is “Sir,” an aggressively open, assertively sexual (Spooner went so far as to insert recordings of sex with a man in Madrid) 13-track album, which will be released next spring. It is previewed by Fischerspooner’s first museum exhibition of the same title, an internet-specific photo-video installation at the Museum Moderner Kunst in Vienna, Austria in collaboration with the photographer Yuki James. At Stipe’s Chinatown apartment, the two discussed their shared experiences, gay party music, and social media-induced narcissism.

Ann Binlot: Michael, you first met Casey when he was 18. Do you remember where?

Michael Stipe: We met on the dance floor. He was in a white t-shirt and was easily the most fun person in the room. It was in Athens, Georgia, a very small community. I just pointed at him and said, “You’re coming with me.” That’s my memory of it.

Casey Spooner: Really? [Laughing.] I don’t remember.

Michael: Well, I remember the pointing.

Casey: I remember you had incredible hair; you looked like a lion. You had the biggest, longest, curliest hair and you wore B.M.X. pants.

Michael: They were kind of see-through when I got sweaty.

Casey: Oh, I didn’t notice that. At the time I was “not gay,” so I was kind of avoiding you. Then you sat next to me and talked to me. But we didn’t really talk again until the day you passed by my car in front of the C&S bank. I said “hello” and you got so excited running around my truck acting like it was the most amazing truck in the world. It was cute. You had just bought giant sunglasses and were showing them off. It was a strong look for Athens in 1988. That’s when you asked me on our first date that you were three hours late for!

Michael: One of the things that I love about you, Casey, is that you have an abundant curiosity [for] just about everything, which I think is essential in an artist. You are absolutely fearless, and are able to go full bore into anything that interests you. I often feel a greater sense of confidence in myself when I’m around you.

Ann: Casey, it’s been over eight years since Fischerspooner’s last album, “Entertainment.” You’ve experienced a lot since you started working on your new work, “Sir.” Can you talk about how that has shaped you?

Casey: When I started the record, I was in a very happy, long-term open relationship. So I felt that I had somehow miraculously found a way to live happily-ever-after outside of a heteronormative fantasy. I had a very trusting, loving home—a very committed relationship with incredible communication—and then also this kind of wild freedom to explore my desire and his desire and our shared desires. I was in this place that was thrilling and cool, and I felt that it was also a reflection of contemporary culture: how digital technology and information was impacting people’s intimacy and their sexuality. In the midst of working on “Sir,” that relationship of 14 years unraveled, so the record then became a document of a successful relationship, then chaos, collapse, and then another period of recovery and reconnecting as a single man.

Michael: Speaking as someone who was there watching this thing happen, it had all the feelings of abandonment, insecurity, guilt, shame, and profound sadness. These were all really hard day-to-day, and they are especially hard when you go home alone at night.

Casey: Last summer, on top of my relationship falling apart, my building was sold and I got evicted. I was homeless and I ended up hanging out on Fire Island for the entire season. It was a profound experience, actually, and really shifted my perception on pop music, because I couldn’t deal with all the bad Cher and Whitney Houston remixes. I’m a kid of the 80s, I was raised on Madonna’s “Blond Ambition.” Talk about living a lifestyle. When she made “Justify My Love” and MTV wouldn’t release it, she didn’t even worry and went straight to V.H.S. So I started to understand the need for this more emotive archetype [who is] usually a woman. Prince is still one of my favorite divas though. Being a man of color and insinuating all this bisexuality—it’s hard to beat Prince in a thong, trench coat, and thigh-high boots. By the end of the summer I started to really understand the way gay men are drawn to divas, and the need for the cipher that is Judy Garland or Maria Callas or Whitney Houston. There were so many great summer songs last year, and I do really love a good pop single. I became obsessed with Ariana Grande’s “Into You.” It has this descending melody that is just so heartbreaking. There was something about this heartbreak on the dance floor that I really connected with; every time I heard that song, I literally had to just race to the dance floor. When we were going back to work, I specifically wanted to make a summer song. I wanted to make a queer song, but I really just wanted to make something like our version of an Ariana [track]. Boots, Warren, Michael, Andy, and I ended up making “Have Fun Tonight,” a poppy-pop song that has a kind of queer theme.

Michael: Not kind-of a queer theme, it was a queer theme.

Casey: Yes, thank you.

Michael: The song is about loving someone so much that you tell them, “I’m really tired, you go out, go get laid, go dance, go have fun, go do whatever you want to do. I’m going to be here for you when you’re done.” It acknowledges that there is much more openness in the queer community in terms of an understanding of what a committed relationship can include.

“It’s an important time to have a queer message and to be confident and clear about sexuality and freedom. It’s my job to be an amazing faggot now.”—Casey Spooner

Ann: Your mumok exhibition includes a series of large-scale photographs of you and various other people in your apartment shot by Yuki James. Casey, you were very adamant about not being photographed in your apartment at first. Can you discuss the exhibition and your division between a private and public space?

Casey: I met Yuki in the fall of 2013. I found his work on Instagram and I really liked it, so I reached out to him to do a shoot. He suggested that we shoot in my apartment naked, which were two things that I didn’t do often, or ever. I had done a couple of shoots for “Butt,” but that was years ago. We shot in February of 2014, and it felt like the beginning of a larger idea. I was struggling to reinvent, and I didn’t feel that I could continue this performance artist epic. It had become sort of static: everyone wore weird clothes, and everyone thought they were performance artists. I thought I had to shift the thesis from where we began in 1998, and I was really looking for what that was. To use a personal space as a theatrical space felt like a new way to cut an aesthetic that was connected to the material, but also had a formal quality. From there, Yuki and I mused out on each other for about a year, then we had a request to make a book for Damiani.

Ann: You found a lot of the subjects for the exhibition from Scruff and Grindr, right?

Casey: When you enter the room, the first person you see standing in the doorway is me and Martin Gregory—we had an affair for about three months; we met on Instagram. The next person in the room is this incredible artist and performer, Tate, we just met at a party. Then Thomas Haskett, my engineer. I’ve recorded a lot of songs with him and we’ve spent every day in the studio together for the last two years. There is Caroline Polachek from Chairlift, who sings on the record. The guy painted red is Jason Topete, he’s just an internet crush from Facebook. Next person is Juan Pablo and myself in bed. We did meet off of Grindr, we did hook up, but then we became artistic partners, and so he’s the person in the film. He’s in several photos and he will probably be my primary dancer on tour. Then Kate Valk is photographed—she’s like my sister/mother/brother/queen and was really with me through a lot of emotional turbulence too.

Michael: From The Wooster Group.

Casey: It’s kind of a strange mix: friends, coworkers, sexual connections, but some of the sexual connections actually become friends and then coworkers. There is not a lot of segregation. It advocates that great connections can come from these sort of transient experiences.

Michael: It’s responding to exactly the kind of 21st-century idea of communication, and how it’s radically changed. How we are in the early stages of trying to understand that change. This represents much more of what might seem like, “We’re at the same table or we’re at the same bar, or hanging out together for this one night or this one weekend, or this one hookup.” It becomes someone you have this energetic connection with for the rest of your life. For Casey and I, this goes back to 1989: this was quite a profound and intense time. He went off and did his thing, and I went off and did my thing, and 30 years later here we are working together, writing together, encouraging and supporting each other emotionally. I was going through a lot at the same time, completely outside of the team for this record, and Casey was there for me the whole time. It’s about finding a gang, in a way: the old thing about the family you are born in and the family you create.

Ann: What is it like to be gay in Trump’s America?

Casey: I was devastated after the Trump win, and I didn’t know what to do with myself. I was completely out of my mind; I couldn’t sleep, I was crying, I was confused. I felt claustrophobic, I couldn’t believe it happened, I couldn’t believe I lived in this place where it could happen; I was incredibly depressed and the only thing that helped me was protesting. Being surrounded by other people and being around the energy and the release. I thought it was going to be full of anger, but it actually ended up being an amazing euphoria—it was super positive. I got out of bed the day after the election and went to Union Square and marched all the way up to Trump Tower. It was so healing, and was one of the most beautiful moments.

Michael: I think it’s important to show up. If there’s a rally or cause that you feel strongly about, be one of the bodies in the crowd with a sign or a voice to support your ideas. At the same time, rather than spending endless hours battling idiots or playing whack a mole on social media, or trying to out shout someone else, just listen. Educate yourself about different positions and solutions. Try hard to not fall into the good guy/bad guy, with-us-or-against-us trap, where not much gets solved. Learn to listen.

Casey: Post-Trump, I am really happy, and I feel that it’s an important time to have a queer message and to be confident and clear about sexuality and freedom. It’s my job to be an amazing faggot now.

Michael: Your voice has never been more essential.

Casey: While working on [“Sir”], early on Warren asked, “Can you shift the pronouns so it doesn’t sound like it’s to men?” In the past, I would have said yes. We make the pronouns in our songs’ narratives vague so that you aren’t sure if the story is about a man or a woman. But I thought about it, and I came to the conclusion that whenever you hear a narrative and the pronouns aren’t clear, it’s always an assumed heterosexuality. You never assume that it’s homosexual or trans or bi or lesbian. It became very clear to me that there is no such thing as universality—that I have to keep the pronouns true to whatever the story was that I was dealing with. Deciding to not be specific ultimately leads to a heterosexual assumption. That’s how I’m dealing with queerness in music.

Ann: When you both started your careers, social media didn’t even exist.

Michael: It did, but it was a slower version of it.

Casey: Right, the newspaper.

Michael: Fanzines and magazines like, “Creem,” “Punk,” and “The Village Voice.” Then fanzines came along with punk rock. It was for a specific group, but it moved at a much slower pace, obviously.

Casey: We are living through a time where everyone has a camera, everyone is photographing themselves. The way they are connecting emotionally, sexually, it’s all happening through social media. Everyone is performing the “self,” and using their body as a currency. It’s amplified for gay men, but I know that it is happening for everyone.

Michael: We’re experiencing late-period capitalism where the consumer becomes the product. Through technology we are able to experience a radical shift in what the term “narcissist” or “narcissism” means. At one point, narcissism applied to someone completely self-obsessed, but with no knowledge that they were. Now we have the prime example of rampant narcissism in the White House. You see that reflected in Facebook, on Instagram, and in all the social media platforms. What we’re going through is quite an intense geopolitical, economic, and technological shift. Not unlike what my grandparents experienced from the dawning of the 20th century to their deaths in the late 80s or the early 90s. They saw tremendous, unbelievable changes happen, and we’re experiencing the same thing, but at an accelerated pace.

This article first appeared in Document’s Fall/Winter 2017 issue.