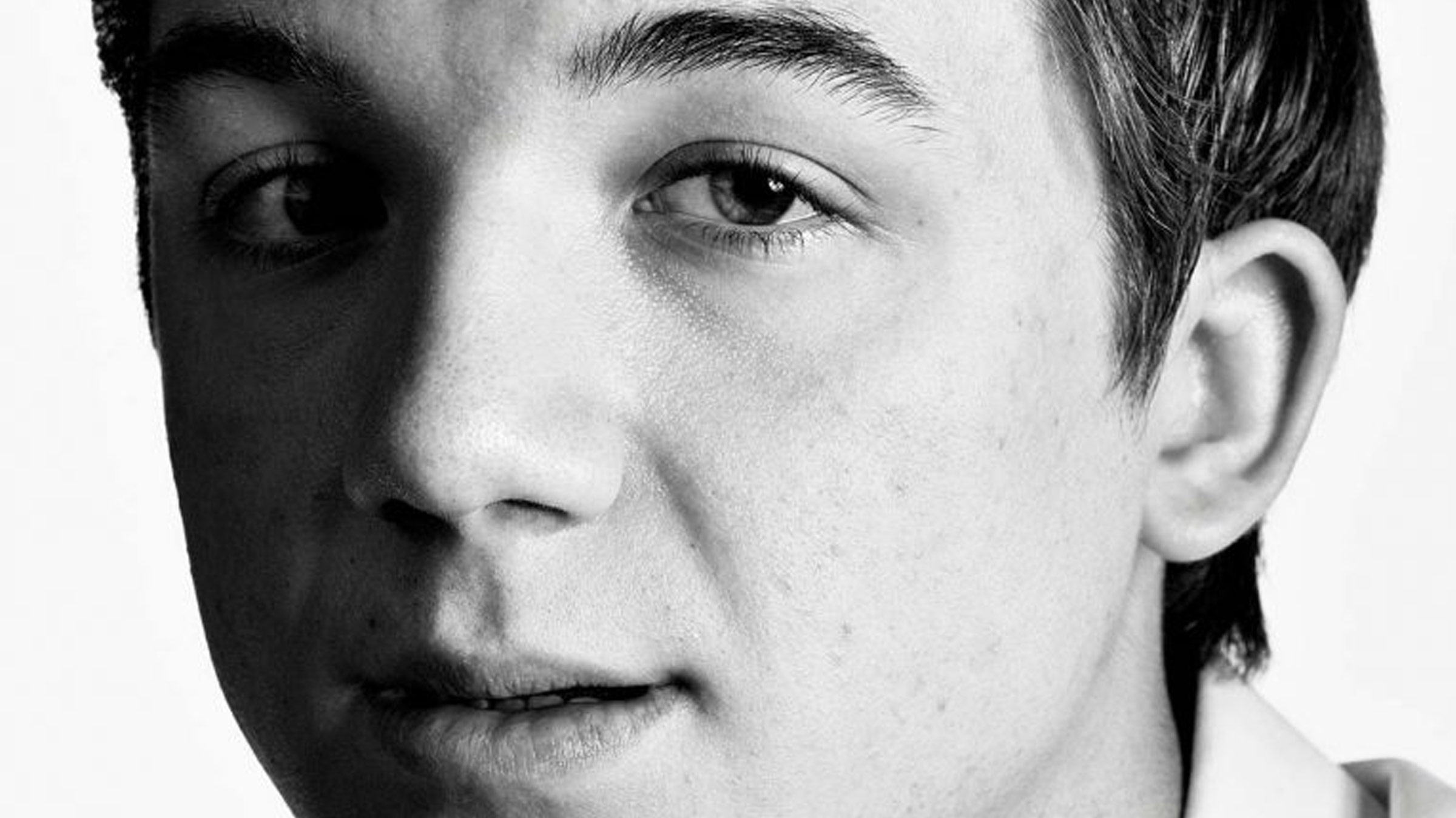

At only 18 years old, Jack Andraka and Adora Svitak have already accomplished more than many adults twice their age have. At 15 Andraka invented a fast and inexpensive method to detect the presence of pancreatic, ovarian, and lung cancers in their early stages. Costing only $0.03 and 400 times more sensitive than the standard test, Andraka’s prototype garnered him the Gordon E. Moore Award at the 2012 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. Svitak is Andraka’s polar opposite. Her love of literature and writing began at an early age; she’d read three books and spend up to three hours writing every day. When she was only eight, she published her first book Flying Fingers. As an activist fighting for education reform, a speaker, and a writer, Svitak is maybe best-known for the TEDx talk she gave at age 12, “What Adults Can Learn From Kids,” which has amassed nearly four million views on YouTube. Svitak interned at the TED headquarters this summer, when the super teens caught up; they chat about growing up in the internet spotlight, what confuses them, and—like any teen—Kim Kardashian.

Above The Fold

LVMH’s Final Eight

Prada Channels the Wonder Women Illustrators of the 1940s

20 Years of Jeremy Scott

Approaching Splendor: Backstage Paris Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2017

Adora Svitak—Do you remember how we met?

Jack Andraka—I got an email: “Do you want to speak at TEDxRedmond, [Washington]?” I thought, “That’s the girl from TED. I saw her video. Sounds cool.” It was my first TEDx.

Adora—We were all really excited. We’d come at that moment before 20 million other TEDx events asked you to speak. We met after you won the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair.

Jack—Going to ISEF was my childhood dream. And then I won it. I didn’t know what was going on. I was just some ninth grader from Baltimore. I thought, “What’s going on here?” The organizers said this would go away in two weeks. Now it’s been four years. What did you anticipate when you first talked at TED?

Adora—I didn’t think it’d be a big deal. Mostly, I was waiting for the YouTube video to share with friends. And then [nearly] 4 million views later…. Sometimes I wonder how long it’s going to keep going. Do you ever worry about being a one-hit-wonder?

Jack—I think, “Will I escape my pancreatic cancer test?” Since then I’ve done other research. My new projects are so much cooler!

That’s one of the biggest parts of scientific breakthrough: communicating your ideas in a simple way. In the age of science in 140 characters [on Twitter], you can definitely tweet “I created a star in a jar,” or “I discovered the Higgs boson!”

Adora—What are your cooler projects?

Jack—Nanorobots: super-small robots I program with DNA that go into your body to figure out how to treat your cancer. They can combine different drug therapies at different dosages to personalize treatment. I programmed an artificial neural network, so they learn as they go and evolve with your cancer. I was also thinking about inserting genes into your cells to fill their genetic work: I can make your cells glow green so a surgeon can see them; or knock down resistance so they’re more susceptible to certain treatments—I can program them to do anything I want. There are so many things other than just pancreatic cancer!

Adora—Sounds like it’s out of science fiction. Is there a distance you have to bridge when explaining concepts to people not in STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math]?

Jack—That’s one of the biggest parts of scientific breakthrough: communicating your ideas in a simple way. In the age of science in 140 characters [on Twitter], you can definitely tweet “I created a star in a jar,” or “I discovered the Higgs boson!”

Adora—No one really knows what a Higgs boson is.

I realized that I didn’t need to be extroverted. It was okay to not go to two or three parties every week—all this stuff that I forced myself to do, because that’s what I thought the college experience is supposed to be. Like frats.

Jack—I’m rusty on what it is too. There are quarks and other things out there. I just learned about it, but it still confuses me.

Adora—You’re human! The day of my astronomy final, I asked, “What’s bigger, the Solar System or the Milky Way?” [Laughs]. American education, y’all! People must tell you you’re really smart.

Jack—But I don’t know what a preposition is, and I’m pretty rusty on how to use a comma. Things you understand! I write and pepper my writing with a lot of commas. “It kind of looks good here.” Also I’m still confused about the vast majority of US history.

Adora—It’s inspiring to say, “Look at me. I do cool things, but I’m not great at everything.” Do you ever find it hard to try to maintain an image of having it all together?

Jack—Sometimes, especially at school, it’s almost expected of me. The adjective “smart” has devalued throughout my life. Initially it was, “Wow, it was cool,” but now it devalues all the hard work I still have to do to achieve something. “Oh, you don’t have to work for that; you’re smart! You should instantly get it.”

Adora—I used to [try too], but now I’m more open; I wrote about getting a terrible score on the math section of the SATs.

Jack—It’s also really interesting being a minority in science. Outwardly I’m a straight white male—well, not straight, that’s one thing I’m not! I’m a white male in science. At the same time, I’m a member of the LGBT community. It was disheartening when I started, as science is dominated by heterosexual giants. You never see a gay scientist. I would go to science fairs, and there wouldn’t be a single openly gay person. I thought maybe I wasn’t allowed to be in science. Oftentimes, in the gay community, we are informed to be a stereotype: an interior designer, a fashion designer; gay people need to have a good fashion sense and go to the gym often. I do not fall back on stereotypes like that.

Adora—You don’t do the fashion part at all. At all! Laughs.

Jack—No, not the fashion! I really had to wrestle with my identity. To balance my gayness with being a scientist. I was “a scientist first, then gay second.” But now I’m “gay first, and scientist second.”

Adora—You’re going to be living on the best coast pretty soon.

Jack—West coast, best coast. We’re going to be university rivals; I’m going to Stanford and you go to UC Berkeley.

Adora—We’ve always been rivals! So I don’t think that makes a difference. Are you excited or nervous?

Jack—I’m really worried about academics. I’ll have to really study. I’m anxiously awaiting it. How did you find the transition?

Adora—It was a lot better than I thought. I realized that I didn’t need to be extroverted. It was okay to not go to two or three parties every week—all this stuff that I forced myself to do, because that’s what I thought the college experience is supposed to be. Like frats. Don’t join one! You’d be actually great at it, which is terrifying.

Jack—[Laughs]. No, I would never! I’d be really good at a sorority, though. Some fraternities have girls who help to support the frat called Rosebuds. I’ll be that, but for a sorority!

Adora—You’d be good in a frat, you work out all the time. That’s all frat dudes do: work out, eat, sleep, drink beer, have questionable….

Jack—I’m going to the national championship for kayaking in two weeks! I’m going to hopefully qualify for the worlds after that.

Adora—That’s so exciting! When did you start kayaking?

Jack—Well, my parents met on the river. When I was 18 months old, they couldn’t find a babysitter; they said, “I guess you’re going on the river with us.” I’ve been kayaking ever since. Often times there’s this image if you do science, you can’t do athletics. But it’s important. Sometimes [kayaking] makes me really anxious; I feel like I’m going to die on the river. It’s my adrenaline rush. Solving the way down the river is like a math problem, strategizing your map. It’s fun!

Adora—Would you say math is your first love, more than science?

Jack—Definitely. I first got into math way early on, when I did the math program Kumon. I love what it gave me, but hated it while I did it. We’re still finding Kumon packets I hid that I avoided doing! I got really into science because in my middle school, science was a game—the science fair was mandatory. It wasn’t your ordinary, “Oh, let’s make clay volcanoes.” No—it was Hunger Games style. If you did well in science and math, you would get special privileges. It was a corrupt setup, but at the same time worked really well in my favor.

Adora—You were the beneficiary of a corrupt system. A lot of time I question the role to which industry and business has evolved, because so much of the rhetoric around education is “career readiness.” On an idealistic, thoughtful, and philosophical level, I don’t think school is about getting a job at the end of the day; it just should be about becoming better people.

Jack—School shouldn’t be a burden; it should be about self-discovery, gathering a bunch of knowledge. I still have no clue what I want to be when I grow up. Do you have your life planned out?

Adora—In middle school I thought about political science, and I would try to be president— but then I got really disillusioned. Do you think you would have found science had it not been for your family having an overwhelming interest in it?

Jack—I think I would have gravitated towards it, because naturally I like all aspects of it. But at the same time, I really enjoy writing. I could have gone that way, but I wouldn’t have been nearly as good of a writer as you. I’d think, “Where does this comma go?”

Adora—Jack Andraka, the poet. It’s still in the cards. What do you think about Kim Kardashian?

Jack—It’s my guilty pleasure watching Keeping Up with the Kardashians! I get my fill of drama watching these reality tv shows.

Adora—You don’t have enough of an adrenaline rush kayaking or working on cutting-edge research? So you turn to…

Jack—Kim Kardashian, yeah.

Adora—Well it’s true, we all have our faults. Laughs.

Jack—You watch and think, “Oh my god, how is this a thing?” It’s strangely addictive and so entertaining. I’ve downloaded her app. I got to A-list status. It is really fun! What’s your guilty pleasure?

Adora—I bought a Vogue; and all those perfume inserts, I ripped them out and sniffed them. I felt like a rich woman! [Laughs].

If there was a young boy or girl debating between humanities or science, but thought science would be too hard, what would you say?

Jack—I’d be worried they could be the next Shakespeare! But I’m biased. A lot of people view science as a cold-hard discipline, where everything is a straight fact, a graph, or an equation. It’s not that at all. It has a very human component, which comes from curiosity to explore the world around you and find the solutions for the world tomorrow. That’s what’s so cool. There’s no definitive answer. There’s empirical evidence for a hypothesis, but we don’t know the answer. It’s there somewhere—you just have to find it. That exploration is really important for me.

Adora—A lot of schools—especially the way we’re taught science and math—don’t necessarily emphasize this discovery.

Jack—It’s true across all disciplines, but it’s really detrimental to science. We have a bulimic learning system, where you take as much information in from a textbook and puke it out on a test. That’s not the way to learn. You learn from doing, from hands-on activities. Not labs where you know the answer, but by designing experiments. When I was younger I wondered whether cells burst more in a basic solution or an acidic one. I didn’t feel like googling it, so I did an experiment.

Adora—I think that’s the only time a human has ever said that.

Jack—When you don’t know the correct answer, discover it—it’s the process. We should have more teaching like that. And also more individual research. Like science fairs. The type of structure where you come up with ten questions and you investigate. That’s a really neat way of teaching science. If I had learned all the stuff I needed to know for my research on cancer in a traditional classroom, I’d have never have been able to do what I wanted. I’d have been like, “Oh my god, so boring.” But I learned that on my own, because I had that internal motivation.

Adora—We need to focus less on teachers as people who share what kids should be learning, but act as learning facilitators to share how kids should be learning. With technology—computers and smartphones—and how easy it is to access the world’s knowledge, we should be moving towards that model.

Could you see yourself being happy as someone who is self-sacrificial, who puts personal and family life on the line just to bring innovation to cancer research?

Jack—I’m still wrestling with that. Initially I just wanted to do my research and nine times out of ten stay in the lab. Now it’s much better to get out of the lab. When you’re a happy scientist, you’re also a helpful scientist—you come up with more ideas.

Adora—I used to associate misery—or if I was angry—with productivity. I’d write a lot when I was really sad. That wasn’t necessarily my best writing. It was very emotional and from the heart, but I much prefer the ideas that come out of happiness. Being happy definitely makes you better at what you do. It’s also a lot more undervalued. We expect to see a writer all alone in their cell. I think the equivalent would be the mad scientist.

Jack—Exactly! There’s this notion that science is a very singular system, that you can’t collaborate with anyone—that you’re all alone in the lab. While that can be true when I was alone until 12 o’clock, it was my choice. I really think I bounce ideas off people—everything we do is collaborative. As a species, we have to have that human touch.

Jack Andraka recounts his story in his book Breakthrough, in stores now. Adora Svitak will be speaking at TEDxKyoto November 8, 2015.