Cult icon, chronicler of chaos, and poet of the absurd—Cookie Mueller’s Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black is a sacred text of survival, wonder, and wit

Whether from my impatience or an inherent bitchiness, I’m often worn down by collected works. No matter how much I might enjoy an author, by the end of their collection, I’m lethargic. Pleasure turns to gluttony: I feel almost sick at the thought of stuffing another word into my mouth. But reading Cookie Mueller’s Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black had the opposite effect. When I finished the last page, I was hungry for more.

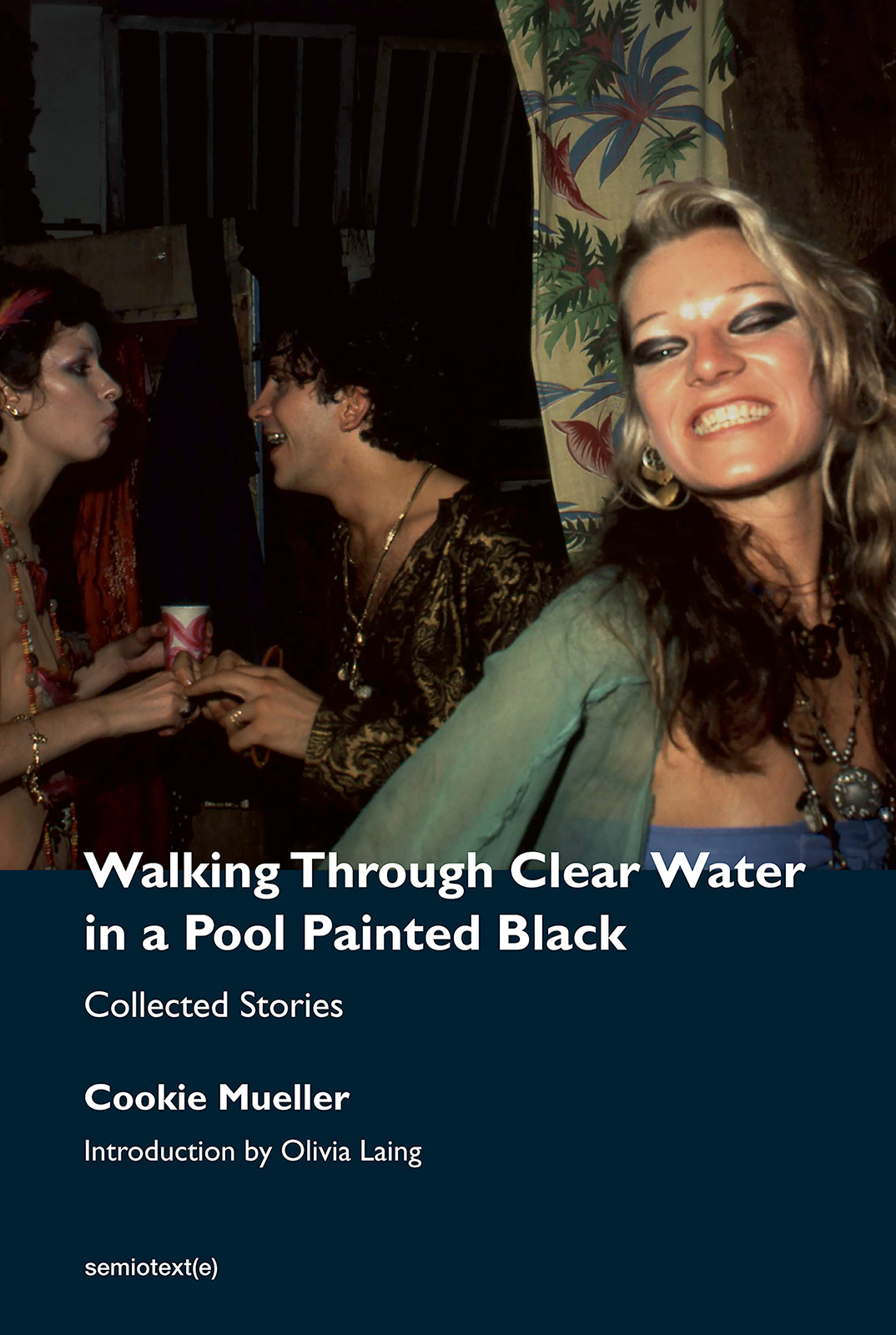

Cookie Mueller, née Dorothy Karen Mueller, was a venerated writer, cult movie star, and art critic in New York throughout the ’70s and ’80s. A subculture darling, she carved out a space for herself that was communal and irreverent. Her stories are dotted with cameos: she was a Dreamlander, even inspiring the title of John Waters’ Female Trouble after describing her collapse from infected fallopian tubes with those very words. When Nan Goldin first met Mueller, she recognized her from Waters’ films. Goldin went on to capture Cookie’s striking beauty across thirteen years of friendship and hundreds of photographs.

This collection of Mueller’s work, first published in 1990—a year after her death at 40 from AIDS-related complications—was reissued in 2022 by Semiotext(e), incorporating previously unpublished work and an introduction by Olivia Laing. It beautifully threads together autobiographical vignettes, short stories, her Ask Dr. Mueller advice column for the East Village Eye, her art criticism for Details magazine, and a coda. The throughline is a wit that cuts through the pages, and an equanimity that’s not quite a nonchalant shrug or a bitter middle finger, but rather a warm embrace that life is what it is—and it can be wonderful.

I was reading Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black at a Brooklyn café when I heard someone gasp, “Oh! Cookie!” I was so immersed in the text that I thought I might be hallucinating. But I wasn’t. Two men by the café windows were whispering. All I could really hear was her name, repeated like an incantation: Cookie. Cookie. Cookie.

“Yes?” I asked them.

“Oh, nothing! We’re just glad someone is reading Cookie Mueller. You know? She was a beloved community member.” He said this with his hand over his heart, like he was pledging allegiance to her memory. I was struck by the softness in his voice—the intimate reverence with which he spoke about someone who likely died just as he was being born. Yet the more I read her book, the more I understood his sentiment. Mueller’s voice doesn’t demand distance: it beckons you, delivers you to the pews, and converts you into a Cookie evangelist.

Mueller famously said she was not wild—she simply stumbled upon wildness. However, “stumbled” feels stingy. It would be more accurate to say she tripped and fell into a bottomless pit of wildness. Her autobiographical writing unfolds across three parts, chronicling chaos across Baltimore, Provincetown, and New York in chronological order. These fast-paced snippets are imbued with a shameless candor that doesn’t deny mistakes, but simply doesn’t mind them. They’re far from formulaic confessional writing—more like secrets swapped across the dinner table, told with a cigarette in one hand and a drink in the other.

In her short story “Haight-Ashbury — San Francisco, 1967,” she smokes with the Manson Family, narrowly avoiding Charlie himself, and later that day summons demons at Mount Tamalpais. She survives a 1969 abduction and rape in Elkton, Maryland. In “British Columbia — 1972,” she recounts the time she burned down a friend’s house and tied her toddler, Max, to a tree while she desperately argued with housemates about which artwork to save. In 1983, heartbreak drives her south to New Orleans, where she hunts for a cure for loss and is gifted a healing stone by a spiritual practitioner.

These slices of her life wield so much intrigue—and so many drugs—that they would undoubtedly knock the modern It Girl (the no-drinking, seven-vitamins-a-day, gut-health Clean Girl) flat on her back and into a coma. Diagnosis: too much life. Yet what really shines through these vignettes is her disinterest in self-pity, her authenticity, and her biting humor (it’s no wonder someone once mistook her for a drag queen). After reading her work, you won’t just believe you know Cookie—you’ll believe you love her.

“Cookie was Jupiter on Earth, welcoming everyone into her orbit, aware we are all adrift in the same cosmic current.”

Though some of her tales descend into the ghastly, Mueller sidesteps the seduction of spectacle. Instead, her trauma is rendered with wryness and humanity. Olivia Laing, describing this facet of Mueller’s writing, calls it tactical: “Some things, especially pain, don’t need to be spelled out, but rather defanged”—a maneuver Cookie executes expertly. She never conceals the scope of the horror, but disarms it enough to survive it. Another weapon in her arsenal: lush, sensory, cinematic prose that tempers the grit of her adventures with wonder. Phrases like “a magenta crush of bougainvillea blossoms” and “it was as if the rising moon had exhaled a cool sigh” are sprinkled throughout the narrative, revealing Mueller’s gift for capturing a transcendent beauty that swaddles you, safely sinking you deeper into the story.

Many of her escapades thrive on spontaneity and human connection (and cheap, impulsive flights that our current economy doesn’t facilitate). She was Jupiter on Earth, welcoming everyone into her orbit, aware that we’re all adrift in the same cosmic current. In “The Italian Remedy — 1983,” she lands in Rome, then—buzzing with boredom and unhappy with the city’s heat—escapes to Naples. There, she strikes up a conversation with Angelo, the man working at the tourist information center, which leads to her staying with his family. Cookie reminds us that there’s a stasis in planning, and a momentum in unexpected interactions, that’s lost to a chronically online, pre-examined world of Yelp reviews and Apple Maps. When you research a destination and book an Airbnb in advance, there’s not much of a catalyst to chat up Angelo. Do tourist information centers even exist anymore?

Though her lifestyle is now almost unrecognizable, there remains a devastating sameness to our world today. She was staring down the barrel of Reaganomics just as we brace for the blow of resurgent Trumpian tariffs. While we struggle to make sense of merciless budget cuts, Cookie had already laid down the red yarn. In her 1986 piece “Ronnie Roach” for High Times, she hypothesized that a government-manufactured increase in poverty would fuel military enlistment, while surging crime rates would swell police academy applications. Cookie’s AIDS-related death came shortly after her husband, cartoonist Vittorio Scarpati, succumbed to the same disease. She was intimate with the depth of grief of a pandemic—an abyss that could swallow a person whole. We recognize this grief: one we’ve been forced to deny and defer through millions of COVID deaths and an ongoing genocide in Palestine. Cookie’s life is a practice in small forms of protest that stave off this abyss. Her lessons are clear: disrupt repression, delight in humor (even in your darkest moments), forge human connection, and seek refuge in storytelling.

Her fables extend this comfort. They are imaginative little tales—short trips on detergent-soaked LSD—an enchanting mix of absurdity and warmth. I was especially struck by “The Simplest Thing,” in which the titular character, Molly, plagued by the anxieties of city life, seeks to assuage her stress with a trip to the lake. Floating on placid water, she looks up at the surrounding trees and sinks into calm: “She suddenly remembered that she couldn’t separate herself from everything around her. ‘You’re in the soup, Molly,’ she told herself. Molly was indeed.” It’s a quiet truth that permeates every corner of Mueller’s work: to be alive is to be cooked into the cosmic chaos—irrevocably bound to everything around us. In surrendering to this enmeshment, there is not only a sense of peace added to the tumult, but the hum of shared humanity.