In the dreary Coachellscape, the electronic duo Snow Strippers offers a nostalgic reminder of a time when music festivals were still fun

If I had known what this Coachella press pass would do to my inbox, I never would have grifted one in the first place. For the past several weeks, I have received no less than a dozen emails a day pushing brand activations, corporate afterparties, and of course, performances. It is clear that even with dwindling attendance and long past its flower crown-toting prime, Coachella remains a major moment for artists, emerging and established, to cement their place in an ever-fleeting zeitgeist. But one pitch catches my attention: an overly casual email from the publicist for Snow Strippers, the unruly EDM project of former Tinder matches Graham Perez and Tati Schwaninger.

When I give their publicist a call, I am immediately vibe-checked. This is not without reason; the duo are elusive and notoriously press-averse, giving little more than one-word answers in rare interviews. Ultimately passing said vibe check (it’s a good thing we have both regrettably dated DJs), she tells me she will do her best to make this profile happen. They aren’t divas, she reassures me, but they do resist definition. As I pass by their billboard on my drive to the desert—tagged “GRIM” in big bubble letters before being retagged by their label exec, Evilgiane of Surf Gang—I have little confidence that we will connect at all, uncertain if I am there for work or if I’m simply another Coachella attendee.

My friends and I show up early on the first day, braving the 100-degree weather to see Bambii at the Do Lab. Her set is immediately canceled due to a sound issue—despite the festival occurring at this same location almost every year since 1999—foreshadowing an exhausting and tech-deficient weekend to come. This gave us plenty of time to get a lay of the land: people waiting in line to get inside a bright orange structure, where they would wait in another line to buy an 18 dollar Aperol spritz; a horde of influencers berating us for walking through their photo shoot set up in in the middle of a stage entrance; sets by favorite artists riddled with gimmicky guest appearances and more tech issues. The indefensible presence of Travis Scott is matched with an indefensible Travis Scott popup space, fitted with a fighting ring and a Vetements-branded tattoo studio. We end the first day dust-coated and spiritually defeated, not yet seeing any redeeming traces of Coachella’s once-prolific cultural legacy.

Day Two begins with a few electrolyte tequilas in a lazy river at an off-site pool party, offering some respite. After huffing secondhand fumes at Charli XCX in one of the worst crowds I have ever experienced, my friend heroically suggests that we ditch the masses as they flock to an ironic hyperpop set by an equine DJ. For this I owe him my life. We end up at the smaller-stage set of Portishead’s Beth Gibbons, which is almost completely overwhelmed by the Green Day show roaring from mainstage. We find a partial fix by standing directly next to the front-right speaker, quickly forgetting the persistent echo to witness a perfect performance. Halfway through, I notice I am standing next to former Coachella mainstay Sky Ferreira. Suddenly I am overwhelmed with nostalgia for the heyday of American music festivals—back when everything was a little less embarrassing.

My love for music began when my dad took me and my best friend to Outside Lands in middle school, setting us free to roam the festival grounds with completely undue trust. I spent the month beforehand listening to each artist through iPod torrents and watching YouTube music videos from the likes of Santigold and Wavves. The festival was a place of discovery back then, and soon I was spending all my babysitting money on DIY beach punk and witch house shows in musty basements and at the Ché Café, finding much-needed community in my teen angst among strangers. I will never forget seeing Grimes at the tiny Soda Bar on her first American tour, then a quietly distinctive force a decade before her AI-fueled Coachella flop.

Snow Strippers has a prime booking, closing out the indoor Sonora stage on the final day of the festival. By the time I get there, my brief heat and influencer-induced misanthropy has been replaced by a prolonged melancholy. I can’t help but feel like I am walking on the hallowed grave of what festivals used to be. Some good music prevails—Amaarae, Arca, and The Marías stand out—but I wonder if the connection and discovery of the early 2010s festival exists at all for today’s teens, or if it is simply a place for PR stunts and predatory brand activations. As I enter the tent, I receive a relieving answer.

Sonora is packed full with the standard Snow Strippers crowd—baby-faced, heavily tatted, and much better dressed than the average Coachella-goer. I begin to forget about the strange world outside. It feels more like the shows they thrive playing, smaller venues lax ons fake IDs. When Tati and Graham come out, their influence is obvious; I see now that the crowd is dressed a lot like them. Beginning with “Aching Like Its” and tearing through their popular discography with little pause, they are in their element. Graham’s mixing and Tati’s live vocals are the strongest they have ever been. When Tati exits for an outfit change, Graham holds the room with a solo DJ set and easy on-mic bravado. She reemerges in vintage Ralph Lauren she will probably Repop soon. Unlike most Coachella sets, they carry without surprise guests, elaborate staging, or forced crowd work. The energy is contagious, the ecstasy only partly synthetic.

Their publicist finds me in the crowd halfway through and slips an artist wristband over my hand, borrowed from one of their Surf Gang friends. The people on stage are much like the audience, save for an older man in a cowboy hat who turns out to be Graham’s dad. Three teenage hypebeasts stand in front of me FaceTiming their friend who smiles elatedly while he dances around his parents’ kitchen. Between them I can see the crowd clearly. Unlike any other set I’ve been to this weekend, nearly every last person is dancing.

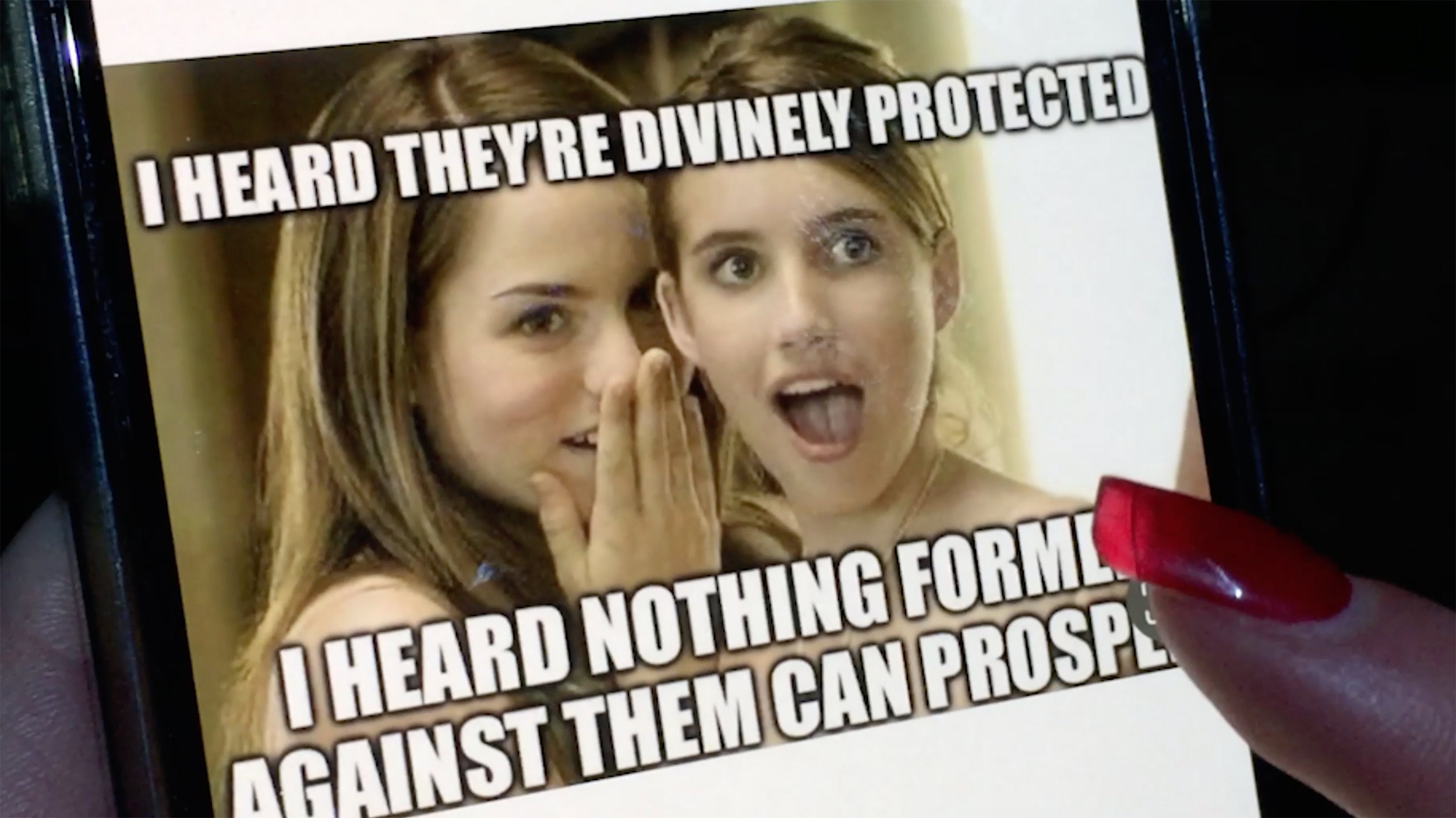

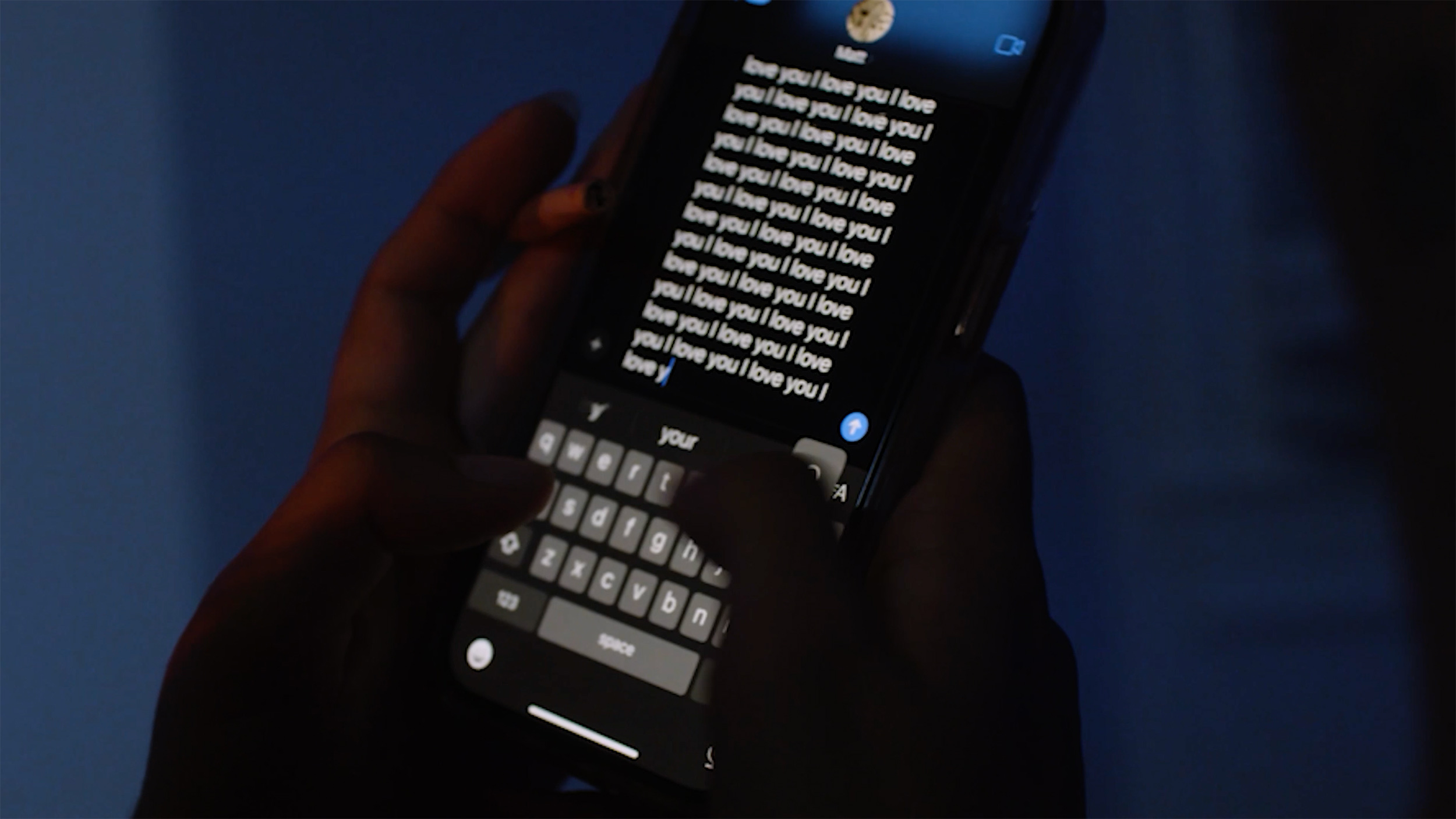

A self-made video runs behind them for the duration of the show, flashing vertiginously between videos of Tati on her phone at the beach, by the pool, and in bed to screencaps of blurry text threads and the FaceTune app, where Graham receives an even squarer jawline. The psychedelic montage extends their recurrent lyrical themes—paranoia, escapism, longing, disaffection—to reveal a sharp visual identity reminiscent of an earlier Internet, more expressive and less consumptive. Their self-presentation is less that of aspirational celebrities and more of first-wave Tumblr users, obsessively curated yet evidently hand-recorded. Before the algorithmic tyranny that gave us front-facing videos and ring lights, this was the offering of our computers: a place to find other freaks like us.

Backstage, I meet their friends, families, and team, the lines evidently blurred between the three. We erupt in cheers when they join us, and I see that their publicist was right: they aren’t divas at all. Tati and I talk fashion for a moment before Graham tells me about his favorite recent show in Atlanta, half-joking that he needs to be on his best behavior when he realizes who I am. They are warm, candid, and evidently relieved I’m not a sexagenarian reporter from InStyle. They glow for the same reason: the fans they’ve cultivated online since their 2021 debut showed up in full force, and it is obvious that they got what they came for.

It isn’t just their music, fashion, or visualizers that make me so nostalgic. They themselves do, too. They remind me of the people I used to meet at shows, ripping cigarettes and fanatically reviewing the setlist that one of us had inevitably grabbed off the stage. I eventually graduated from that scene when I left for college, and I find myself wondering where all those people went. In recent years, I have found parallel community in the queer electronic underground, back to warehouses and basements again but with a slightly older crowd. I spent the whole weekend wondering whether today’s teens had anything like what I did—an escape from the pains of suburban adolescence, a home for the off-beat to build their own taste in the company of other misfits. Snow Strippers has built one such universe, and the appetite for it seems even larger in this time of corporate festivals, corporate music, and a corporate Internet. Even here, in the depths of the Coachellscape, their intervention makes the mainstream feel smaller—like just one of a thousand scenes one can make their own.