In his latest exhibition, 'Blue Roan' at Hannah Barry Gallery in London, the artist brings together 15 years of instinct-driven image-making, carving frames by hand, and letting the work take shape on its own.

Kingsley Ifill has been making books longer than he’s been taking photographs. Before he picked up a camera, he was making zines by hand as a teenager. It was a beginning to what became a lifelong habit of making things from scratch. That way of working by feel, of figuring it out as you go, still runs through everything he does. As a result, his photography blends printmaking, painting, and sculpture–each piece formed by hand, literally.

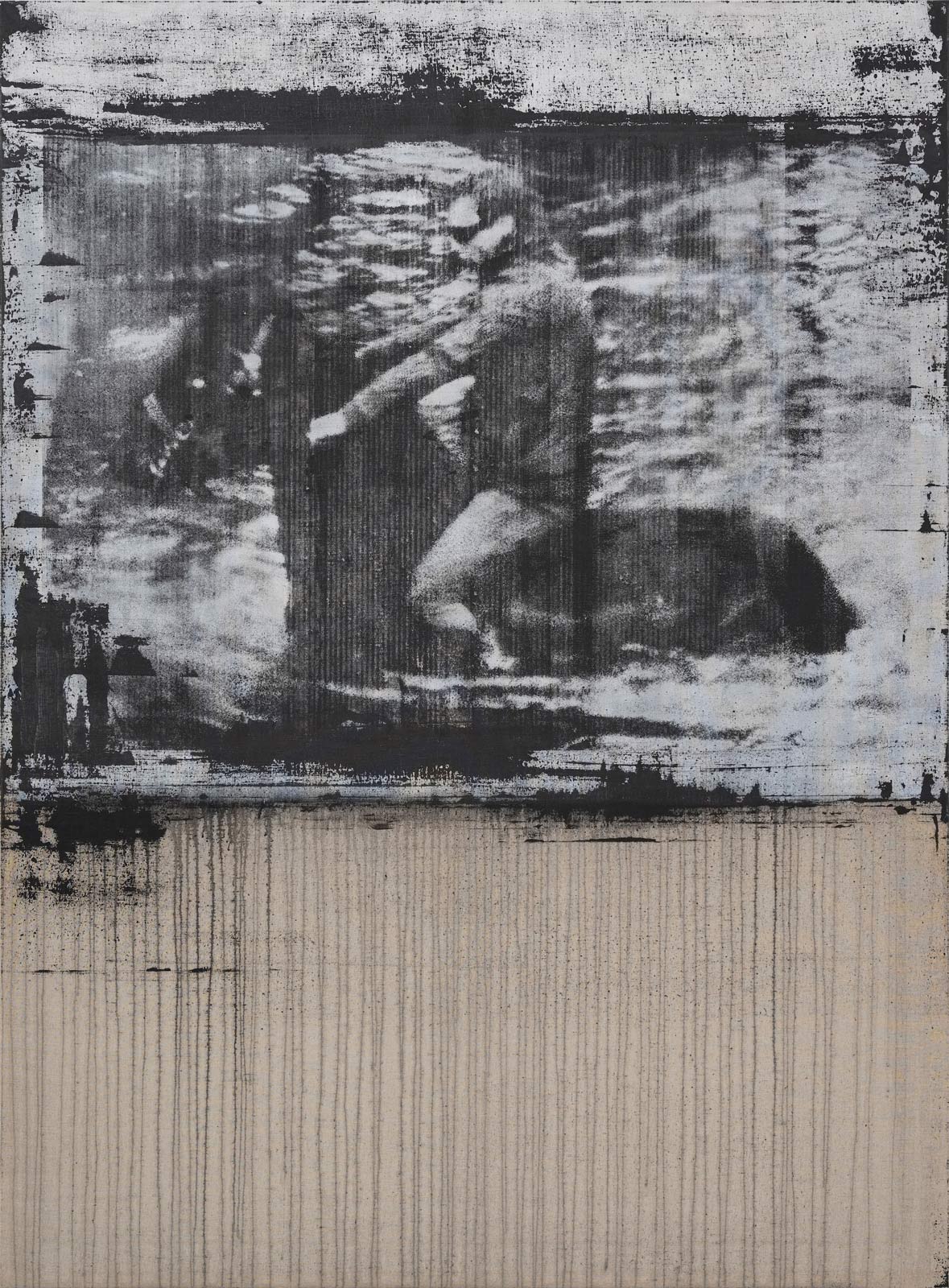

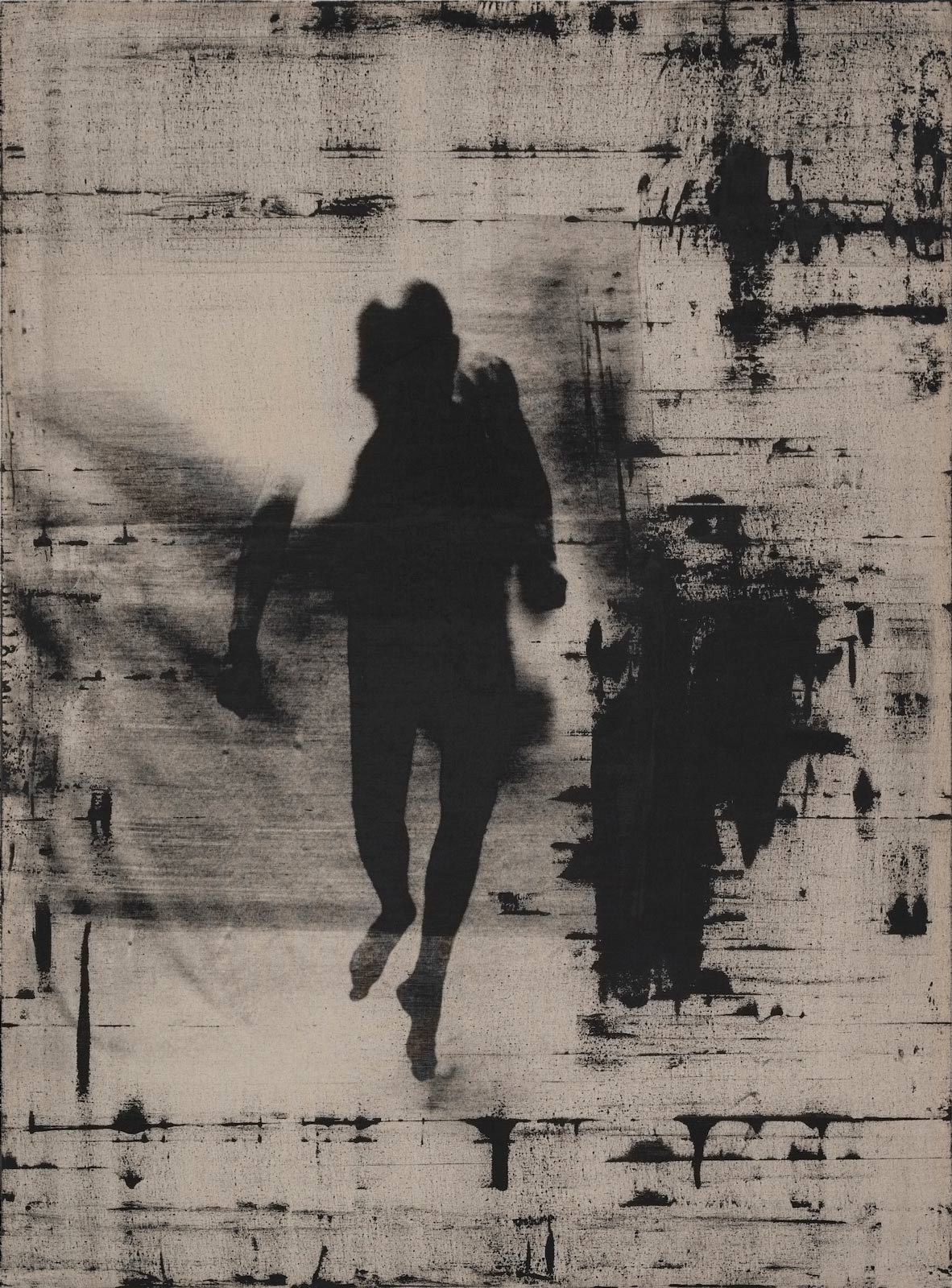

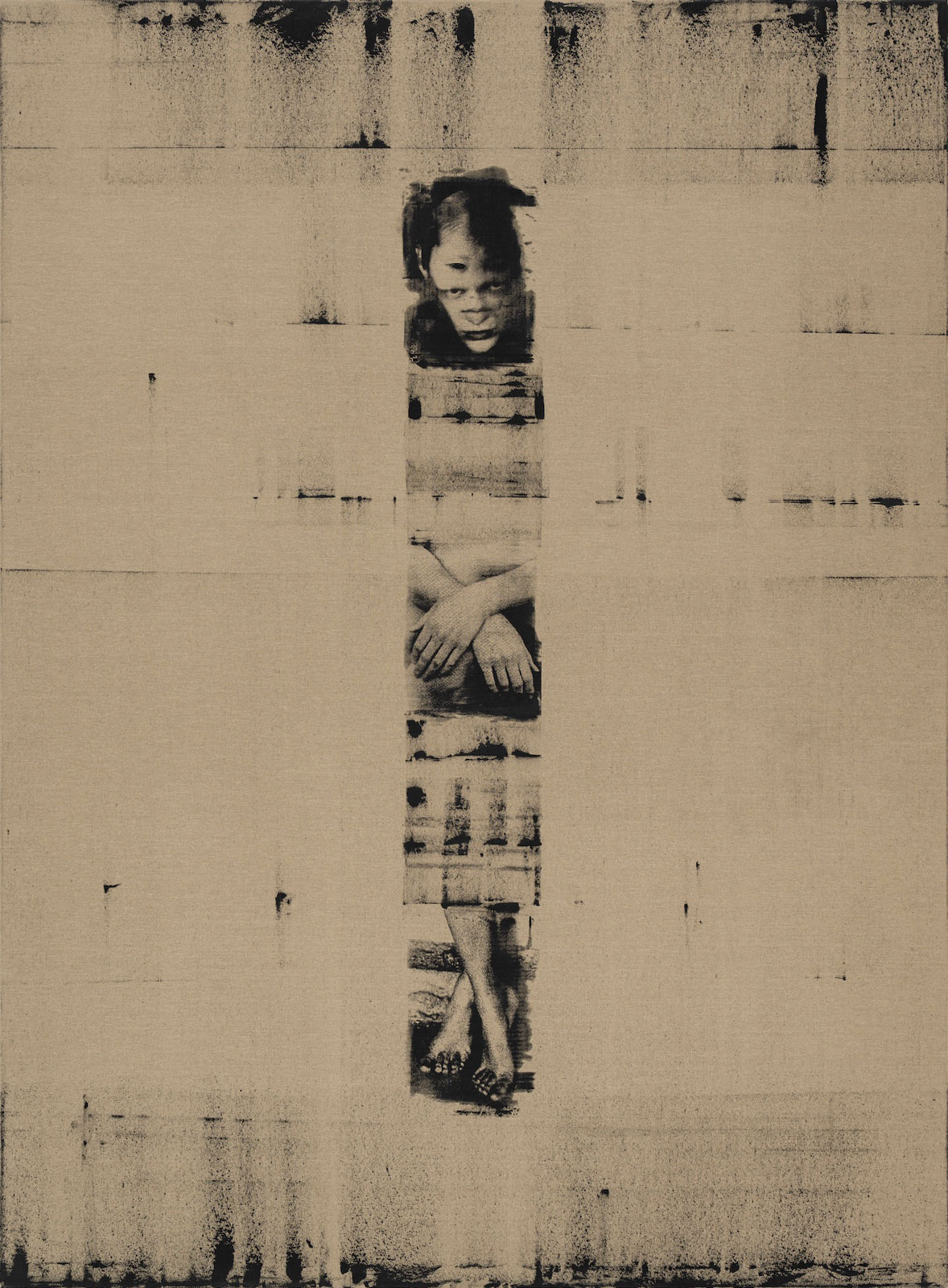

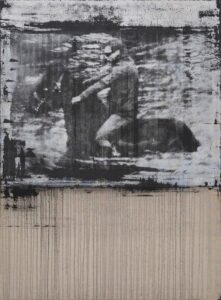

This hands-on approach defines Blue Roan, Ifill’s latest exhibition, on view at Hannah Barry Gallery in London through May 17. The show brings together 18 works made over the last 15 years, spanning decades, formats, and locations. In one photograph, a man on horseback traverses a river. In another work, a pile of snakes appears in acrylic printed on raw linen. Textured and muted in earthy, monochromatic tones, the images read less like a timeline and more like a personal library for Ifill. Each image can stand alone, and when placed side by side, he hopes they invite pause rather than explanation.

Ifill is in no rush. Creating an image might begin with the quick press of a shutter, but finishing it can take years. One photograph, Lifer, taken in 2012, was only recently printed. Others, like Chrysalis (2025) involve silkscreening, a process where ink is pressed through a mesh screen. Works like Keel (2023-2025) use platinum palladium printing, a 19th-century process involving UV light and hand-coated, light-sensitive paper with platinum and palladium salts. Ifill spent more than five years teaching himself that method. He also took on the challenge of carving each of the exhibition’s nine wooden photograph frames by hand. The practices are certainly an extension of his belief in working by intuition and letting the process lead. Guided by instinct, his images emerge through a process he calls “floating,” allowing form to take shape on its own rather than through overthinking. “As soon as I start thinking, that’s when mistakes are made or when I sort of lose myself.”

Document sat down with Ifill over Zoom to talk about intuition, process, and the strange patience it takes to carve a frame over five years, just to house a photograph that doesn’t ask to be explained.

Megan Liu: This is your first solo photography exhibition in London and a culmination of your past 15 years of work. I’m curious to hear more about your process of curating that. Also, why now?

Kingsley Ifill: There’s no real reason why it’s taken that long, but it’s just how it is. When you go digging into your archive of images or the work that’s sitting there, it becomes a matter of editing out what could work together at the same time and have these images that can stand strong enough on their own. It’s the idea that each image can be abstracted from the show and tell its own story without needing these links or this whole body of work to support it.

“I heard someone say recently, “Reason is the opposite of truth.” If you can just allow something to exist without needing to explain it, that feels like the purest form.”

Megan: Going to the title of the show, Blue Roan, talk to me more about that because I understand there’s also a piece called Blue Roan in the show.

Kingsley: It’s Romany slang for an in-between. I was thinking about it as a nonplace, somewhere that doesn’t exist, but also does. That applied to the images and the photography in general. For this work, it felt like all of these in time exist singularly in different parts, but then accumulate into this whole, which is neither here nor there. It’s in a separate place, a nonplace. For the piece Blue Roan, the image was burned and very challenging to make. There were lots of failures in and out of it. It almost became a sort of gatekeeper to the studio when the image was finally finished. When I’ve been walking through the show with people, I’ve talked about this idea where usually you move around to find an image or composition, but in [Blue Roan] the [figure] is still, and the whole river is moving around him.

Megan: I’m also curious to hear how your personal approach or thought process has changed with some of the older pieces you’ve pulled from the archive, compared to more recent work you’ve completed.

Kingsley: This time, there’s really no real difference. That’s what’s kind of nice about it. A photograph could’ve been taken 15 years ago or six months ago and while it seems like a long time, it’s not—in the grand scale of things. I think the process has developed in order to arrive at where [the images] are. It’s been several years of experimentation. An image might start as a contact print, then get scanned on a photocopier, printed as a Xerox, maybe printed in a book, and that book might be scanned again and used in a silkscreen. It’s like this feedback loop. It generates some form of momentum. It’s like a continuation.

Megan: Why do you work with the medium that you do? Photography is everywhere online now, but I feel like you ground yourself to something tangible.

Kingsley: Yeah, almost consciously, I was trying to see and explore what the opposite is of that image you scroll on your phone. On Instagram, you just push past these images you may never see again. They’re just sort of here and then gone. What is the opposite of that, in respect to the archival properties, physicality, and the time dedicated to producing the image? Platinum palladium printing and the archival properties are supposed to last a thousand years, or supposedly forever. You are producing images that are essentially never going to fade away.

Megan: You carved the frames for the photographs by hand.

Kingsley: I’d never done it before, so it felt rare and exciting. It’s the kind of thing that, if I saw it elsewhere, I would enjoy. So I wanted to make something I’d want to see. The carving itself was its own challenge. It’s not record-breaking or anything, but even just keeping consistency within the production takes a lot of mental clarity. You have to be in a certain headspace. If you make one mistake, the whole frame can be thrown off. So it became this challenge where I would have to adjust my life in order to be in the headspace. I’ve got the timeline now to work on these for a week. I’ve got to be sleeping and eating properly. It sounds ridiculous, but that’s what it took and that challenge has literally been five years.

Megan: You also mix painting and acrylic into your photos.

Kingsley: It’s instinctual. There’s no real reason, it’s just what feels right. I’m largely attracted to the archival properties, printing on linen with acrylic is unlikely to fade away. With the paint you are allowing chance to factor in, things are a bit more out of your hands. Instead of imposing your ideas or thoughts about how the image should be made you allow the image to bring itself into the world.

Megan: I noticed this quote in the show’s press release:

“For to know nothing is nothing, not to want to know anything likewise,

but to be beyond knowing anything, to know you are beyond knowing anything,

that is when peace enters in, to the soul of the incurious seeker.”

By Samuel Beckett from Molloy (1951)

Did you choose it?

Kingsley: Yeah. I think it’s about this idea that you feel like you’re going to search for something, but there’s really nothing to find. Even within the production of the work, going out, taking photographs, but everything’s already there. So there’s nothing to look for. I remember reading that quote and feeling something immediate. Even in the show, it’s like… there’s nothing to look for, because it’s all already there.

Megan: Your photographs range mostly on the darker and neutral side.

Kingsley: There’s no specific reason but I do feel like with color there’s a certain number of sympathy which I wanted to avoid. Like, if you see a pink painting, you might think, “Oh, I like pink.” But I wanted to strip all that away, to just direct attention to the image.

Megan: You’ve mentioned that a lot of your work is based on instinct.

Kingsley: I heard someone say recently, “Reason is the opposite of truth.” If you can just allow something to exist without needing to explain it, that feels like the purest form.

Megan: What’s been your favorite part of this exhibition?

Kingsley: Talking to people about it. Learning more about the work than you would do in an isolated setting like the studio. You think you understand something, but really you don’t until it’s out there in the world [and] you get an opportunity to step back, as opposed to being in a bubble. You need to burst the bubble at the studio in order to gain any form of perspective.