With a first solo show and festival debut behind her, the Libyan-American artist is poised for a breakthrough year

Tasneem Sarkez grew up surrounded by online images. An early aughts baby, the 22-year-old Libyan-American artist works across painting, installation, and found objects. In just a few years, she’s built a portfolio that reads like a lossy acid trip through the 2010s into the 2020s, where white noise bubbles over.

What sets Sarkez apart from contemporaries mining similar media is that she channels the internet’s detritus into a language that speaks directly to the complexities of growing up Arab in the Western world.

Surrounded by both the churn of American pop culture and the quiet violence of propaganda designed to draw a line between “here” and “there,” Sarkez’s work bridges digital and real-world divides. As cultural critic Edward Said wrote in Orientalism (1978), “there” has always been intentionally vague, serving as a projection onto which Western fantasies, fears, and prejudices are imposed. Sarkez rejects this imaginative geography, presenting Arab-American identity in a way that dismisses the binary altogether. In doing so, she dissects the idealized fantasies marketed to her generation, revealing the underlying tension between collective memory and the digital echo chamber that once promised to connect us all.

Sarkez admits that her relationship to memory borders on obsessiveness, but for good reason. Raised in Oregon by a father who emigrated from Libya in the ’70s and a mother who joined him in the ’90s, she grew up acutely aware of the distance between her upbringing and her ancestral home. That sense of separation often manifests as a fear of cultural disconnection—of loss encoded in distance—a feeling all too common among first-generation Americans.

On a recent call from her Brooklyn studio, she reflects on the house her father grew up in, a two-story home in Libya that the family nicknamed the “White House.”

“When he called to tell me that it had sold, I felt like a part of me died,” she says. The loss crystallized how quickly even places tethered to memory can vanish.

“Diasporic identities have such a different relationship with things,” she continues. Behind her, the wall is filled with what, at first glance, looks like a random assortment of cutouts, glossy scraps, and personal relics. But, as with her distinctive work, it follows a fragmented kind of logic.

Golden Gun (2025), a painting she debuted in a series for the Milan International Art Fair earlier this week, is a keen example. It looks like the output of a prompt typed into ChatGPT: a painting of gold women’s shoes with gun-shaped heels and a mechanistic sheen set against a soft, dreamy background.

Sarkez pulled the image from a now-deleted Poshmark account. The fact that it came from a resale platform is fitting; the work reads like a simulacrum, where the original context no longer matters as much as its aesthetic currency. Like a result spit out by an algorithm, Sarkez compresses personal memorabilia, cultural iconography, and mass media references in a way that exposes how identity is manufactured, maintained, and mediated through images. Her work captures the mania of contemporary culture, where symbols resurface like spam, recurring across different contexts.

“The title references Muammar Gaddafi’s gun, which he was found with after his death,” she explains. “I remember vividly the image of rebels raising the gun in celebration.”

When Sarkez learned of her inclusion in Rose Easton’s MiArt booth, she immediately knew she wanted to focus on Libya during the early 2010s, a period marked by the Arab Spring: a series of pro-democracy uprisings across the MENA region, including the fall of Gaddafi’s regime. Her fascination with this era stems not only from its historical weight, but from what it meant in her own becoming. “I remember skipping a soccer game to go to a protest,” she says. “It was one of those moments where I realized how different I was from my classmates.”

Much of Sarkez’s research unfolds online. She recounts one story about Gaddafi inviting 500 Italian women to what they thought was a party. When they got there, only about 200 were selected. “He handed them copies of The Green Book, [his slim political manifesto] and the Quran. Then he sat in the middle of the room preaching Islam, promising riches to any who converted,” she laughs. “But events like that weren’t unusual in the Arab world,” she adds. “Beyond the violence, Arab dictators, especially Gaddafi, were so camp.” Theatrical, even.

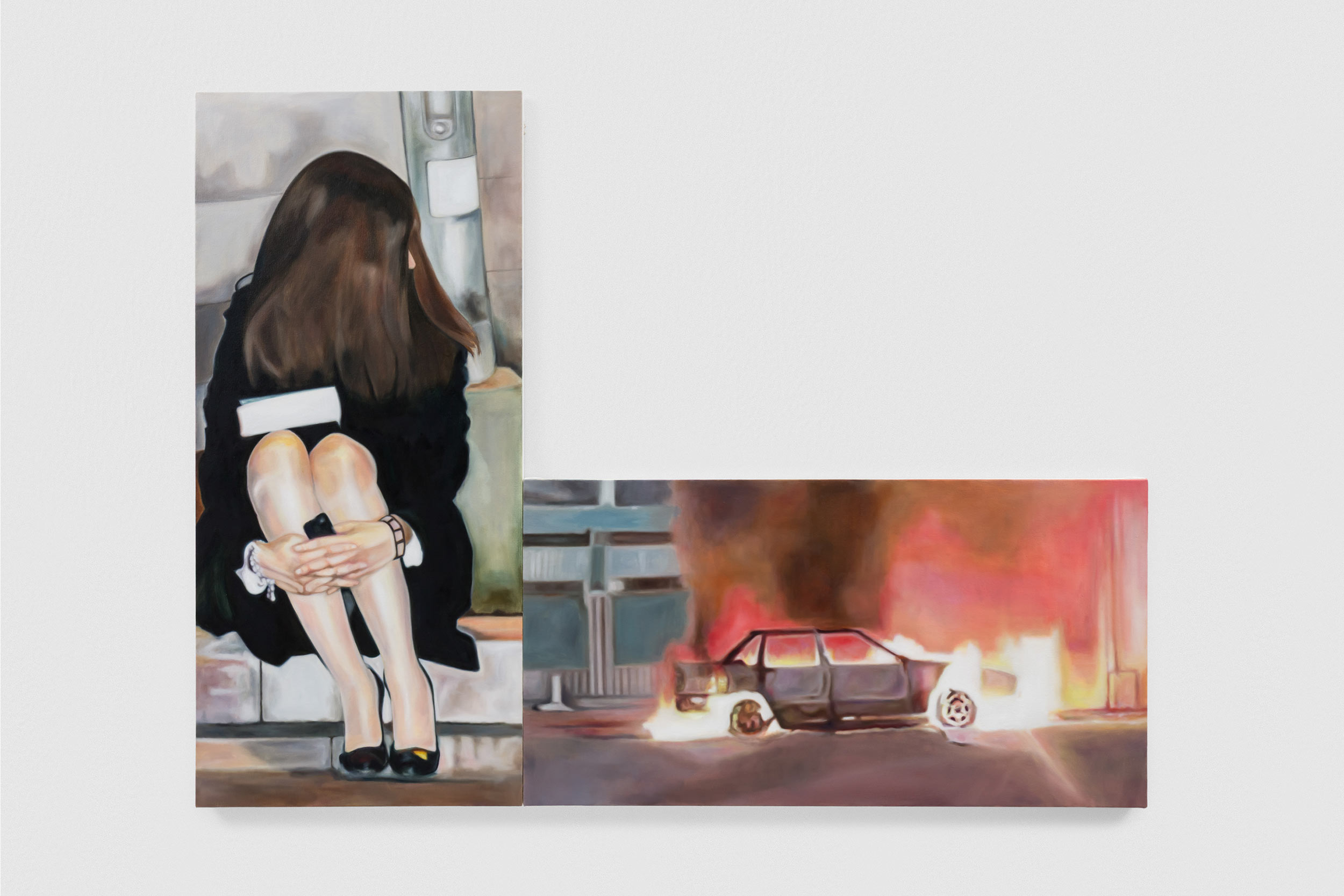

Sarkez engages these stories the way many in the diaspora do: pieced together through news footage, internet ephemera, and in this case, paparazzi photos. On the left panel of Day of Revenge (2025), a cropped photo shows a model slumped on the street, a Quran in her lap. Her face is obscured. She wears heels and a pearl bracelet. You can’t tell who she is, or why she’s there. On the right, a diplomat’s car burns.

I ask Sarkez why she thinks so many Arab artists are grouped under the term “kitsch,” often used to describe work that is overly sentimental, eccentric, or banal. At the heart of it, she says, is “a stripped-down relationship with ancestry.”

“Aesthetics shift so drastically across generations that sometimes we cling to the things our grandparents once had. Preserving them becomes a way to stay connected, like embedding a sense of home into everyday life,” she elaborates.

Art, for Sarkez, is how she learned to love being Libyan. And these days, it’s all she thinks about. “Not just painting,” she clarifies. “More like—the art of the everyday.”

The rising star has been collecting references her entire life. It seems she’s just now learning how to speak in them.

Earlier this year, while in London for her U.K. solo show, White-Knuckle at Rose Easton, Sarkez was approached by a woman who told her she was only the third Libyan artist she’d ever met. “And the second one?” Sarkez laughs. “Turns out she’s my mom’s cousin’s daughter.”

“There are so few of us in this world,” she continues, “which is one of the reasons why I do what I do.” She pauses, then adds: “Someone has to keep Libya on the map.”