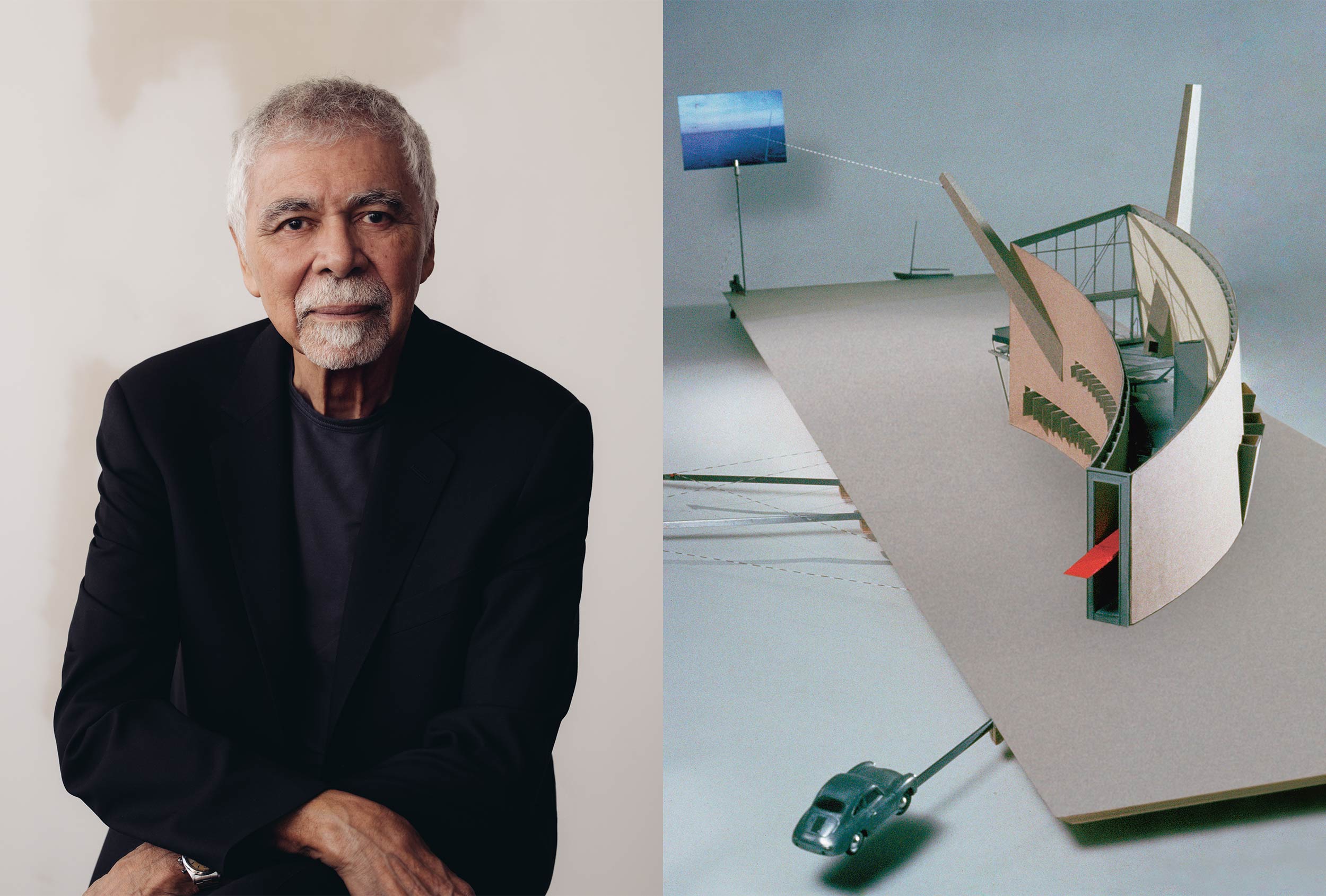

Upon the passing of a founding principal of the studio that trafficked a contemporary art sensibility into architecture, reflections on the work of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R)

To be thinking of the future on the cusp of 90 years of age requires a certain defiance—but this resolute quality was Ricardo Scofidio’s hallmark. “Ric thought of our role as a sieve,” Charles Renfro told me, reflecting on the passing of his longtime partner at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, “to filter things out – to deliver the good and filter the bad from one generation to the next.” Through parks, cultural complexes, and high tech fictions, Scofidio’s works reconfigured and reframed how we experience space itself, offering a project of practice well worth considering nearly 40 years after it began.

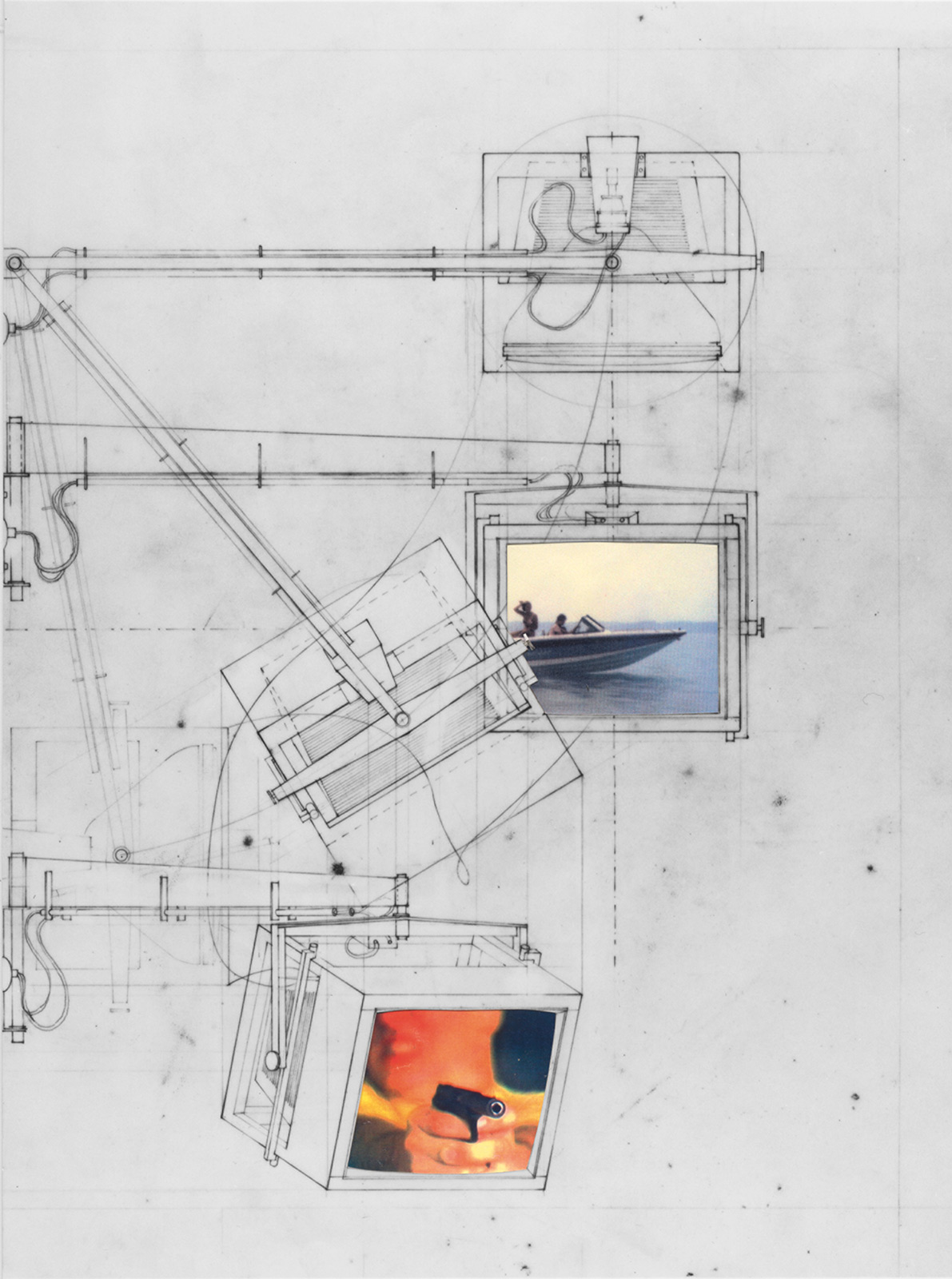

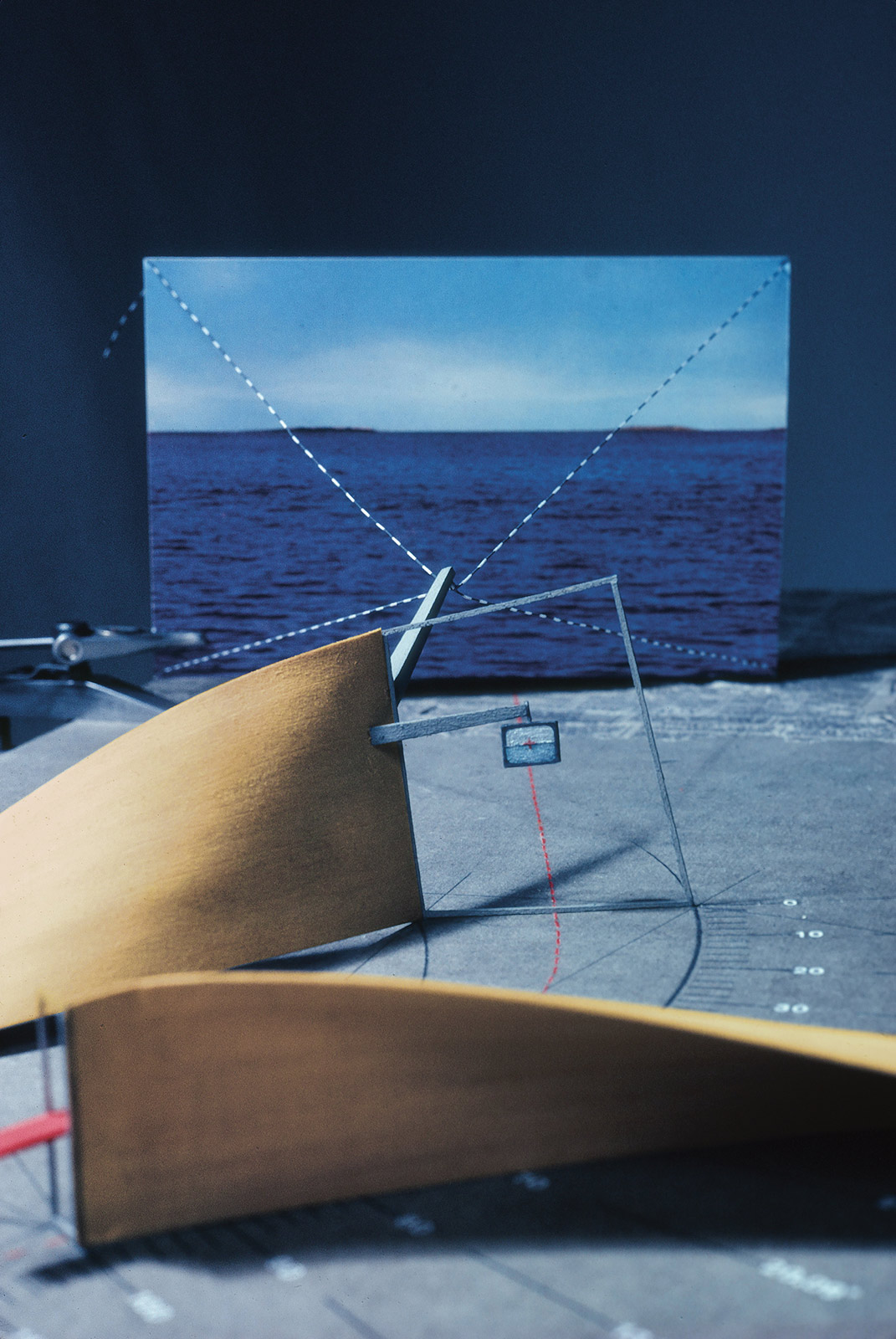

“It’s fabulous, just a door to a window,” my professor clipped. I had made my selection for our next drawing exercise simply for its name and was curious to see it. As I scrolled through documentation of Slow House, the 1991 project for a weekend residence by design/architecture studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro (then just Diller Scofidio), what I found was less vacation villa and more… I wasn’t sure what exactly.

Picture if a house were a slug. Now imagine the slug, drunk on its houseness, has wandered to the edge of a cliff and laid down to rest, looking to the sea. Enter the tiny orifice at its backside and follow a hallway. Continue as its walls tilt out and up until you find yourself occupying its head: a 40-foot picture frame window with gangly antennae. One is a chimney, the other a filming apparatus from which a camera captures images of the horizon and streams them back into the house. On a cloudy day, one can augment the architectural view by using the system to play back a recorded view of a different day; at midnight, a sunrise–Territorial TiVo.

The studio founded by Ricardo Scofidio and Liz Diller in 1981 has authored a clique of dissonant projects scattered around the world. Their work on art and performance institutions, educational facilities, and parks is best recognized in their decade-long effort as the architects of New York City’s High Line, or its neighbor, The Shed. But Scofidio was not determined to be an architect, nor was it obvious the office would make architecture.

The son of a Jazz musician, Scofidio’s defiant sensibility manifested as mechanical experimentation and an affection for automobiles. Frustrated and on the cusp of withdrawal from the commercialized profession at the end of the ’70s, he met Diller as his student. The cocktail of his antagonism and her intellect was powerful, and their relationship evolved – only after she completed the course. The pair “started to share a lot of things: a bank account, a bed, and a practice” as Diller accounts in a 2015 interview.

New York was full of empty spaces and possibility for experimentation. In the context of ’80s financial decline and techno-optimism, and aided by critical formations from feminist and performance practice, the duo churned out a series of works that are severe, intelligent, and sexy. The stage sets are disorienting—an oblique mirror raised and lowered to both divide and double movement on stage (The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate (Delay in Glass), 1987). The installations voyeuristic—6 surveillance cameras that stream images from a bar’s entrance to its patrons (Brasserie, 1997-2000), giant lips coaxing visitors into an abandoned porn theater (Soft Sell, 1993), a plywood ramp to Ground Zero (Viewing Platform, 2001), a mobile metallic ticket booth for a landfill (Gate, 1984). And the fictions uncanny – a cocktail glass with a syringe as its base (Vice/Virtue, 1997), ads in a Turkish airport for a cultural appropriation hotel chain (InterClone Hotel, 1994), a sales pitch for a non-consensual perfume (No Means Yes, 1997).

The critique is formidable, and, among other accolades, wins the pair a 1999 MacArthur genius grant, fueling their research and supporting the development of their most important magic trick to date: to make architecture disappear.

Think of the sprinklers that mist over lettuce at the grocery store. Now think of thousands of them, programmed to act in sync, mounted along a set of walkways roughly the size of a football field. Float this above a Swiss lake on four columns, pump out a fog so dense the structure evaporates, and invite visitors to wander through for a few months. Blur Building (2002) was a smash hit, and you couldn’t even see it.

These experiments, essays, and poems about architecture and the nature of constructed space announced a productive nihilism that suggests not to tear the world down, but to flay it, suture it back together, and inhabit the mutant condition, fast. The 1994 cover of their first monograph Flesh: Architectural Probes accomplishes just as much: Scofidio’s butt cheek on the back, Diller’s on the front, they meet on the spine in an airbrushed crack.

As a third partner, Charles Renfro would soon “wedge his way between those cheeks” (his analogy), as the studio’s newfound prominence brought forth a phase dominated by large scale permanent construction. Bringing impossible ideas to life had been Scofidio’s mode from the start, and nowhere was this tact more present than on the High Line.

New York’s iconic park may masquerade as a found ruin, but its overgrown character belies a 12-year feat of civic soothsaying. It is a magical mechanism on the urban scale that allows us to consider what is already present, en masse. The mundane activities of daily street life are extended onto the surface of the tracks, edited only slightly through decisive operations: no dogs, bikes, or balls; look here, not there; walk this way, not that way. The detail that makes it all possible is also Scofidio’s: a tapered concrete paver that marries pedestrian utility with romantic decay without skipping a beat. The marvelous complexity of orchestrating an infrastructure into faux repose, supposed surrender—repoured concrete, structural skeletons disconnected and healed once more—is all kept quiet to dramatize a lazy Sunday stroll.

The lazy promenade turned out to be anything but. And though the studio operated with comparatively great restraint alongside Starchitect’s Row – residential towers by celebrity architects with a penchant for aesthetic flare – the project nonetheless placed them amongst their ranks. The large built works of the following decades range from overhauls of iconic cultural complexes and new facilities for schools and cultural institutions to public landscapes in contested urban zones.

Rather than articulating a style, these are buildings with attitude; distinct contexts beget particular responses. Clutching her pearls and making sure you know it, the Broad Museum’s lavish facade is as much about protecting the objects inside as it is about reminding us the objects are to be protected. Like the promiscuous reveal of an ankle, cuts in the perforated concrete skin invite us into galleries slipped between the veil and the vault. The galleries of the ICA Boston seem to have climbed a waterfront tower 70 feet into the air. In awkward perch, they anticipate something far off on the horizon. The Shed is a hulking steel clod, a sinuous articulation of the gray zone between public and private space wearing his favorite wheeled sneakers. The 70-meter elbow jab of a walkway floating over Moscow River alights the tensions otherwise subverted across the rest of the expansive narrative landscape of Zaryadye Park.

The studio’s distinct projects of improvement on the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts (2003-2012) and the Museum of Modern Art (2019) see the dissident cyberpunks summoned as counselors, tasked with remediating the vastly different agendas of yesterday’s heroic designers with the needs and desires of users today. In Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall, the trunk of a single tree, sliced infinitesimally thin, warps to envelop the room in synaptic folds. At Julliard, a studio for dancers thrusts out to Broadway, baring it all for the boulevard. At MoMA, a four story stair dangles impossibly from a steel plate, a jewel in a department store window. Rather than masking the nature of incongruous programs or less-than-romantic circumstances, they narrativize them, make them sing. These works offer a vision of a world otherwise, by cutting into the world as it is.

It’s fabulous, just a door to a window.

In personality, Scofidio is remembered as mild mannered, deeply generous in spirit and intellect, and reserved until ready to come in with a kill shot. “Ric never hoarded,” Renfro recalled, “if he invented something he would share it with everyone – gleefully.” Though rarely the spokesperson of the studio, his mark is impossible to miss throughout its projects and in the echo they strike in architects, artists, performers, and passersby.

Slow House, the seaside slug, was never built. Its client’s luck bottomed out with an art market crash, relegating the project to exist only in drawings and models. But through Scofidio’s circus of incisions, his technical wizardry, and his generosity, the studio’s work at large leaves us at a door to a window looking out onto the world we live in. That we may encounter it made strange, urgent, and inviting anew.