Between Guerrilla Girls activism and lyrical abstraction, Stevens's art, currently exhibited At Mary Ryan Gallery and Ryan Lee Gallery, reveals multiple paths for feminist expression

The identity of the original Guerrilla Girls is still a hushed secret. An anonymous activist group that formed in 1985 to protest the lack of mainstream representation for women artists and is still active today, only a few members’ names are known—including the beguiling painter May Stevens (1924-2019). Known for her political paintings that touched on the Freedom Riders and socialist theorist Rosa Luxemburg, Stevens was a close confidant of foundational Black women artists like Emma Amos, Vivian Browne, and Camille Billops who were prominently featured in the retrospective Friends and Agitators at Ryan Lee Gallery in 2021. Stevens herself was white, one of few non-Black figures in group photos, occasionally followed by her husband the painter Rudolf Baranik (1920-1998). Today, In two shows across New York City, different sides of Stevens’ work are on display.

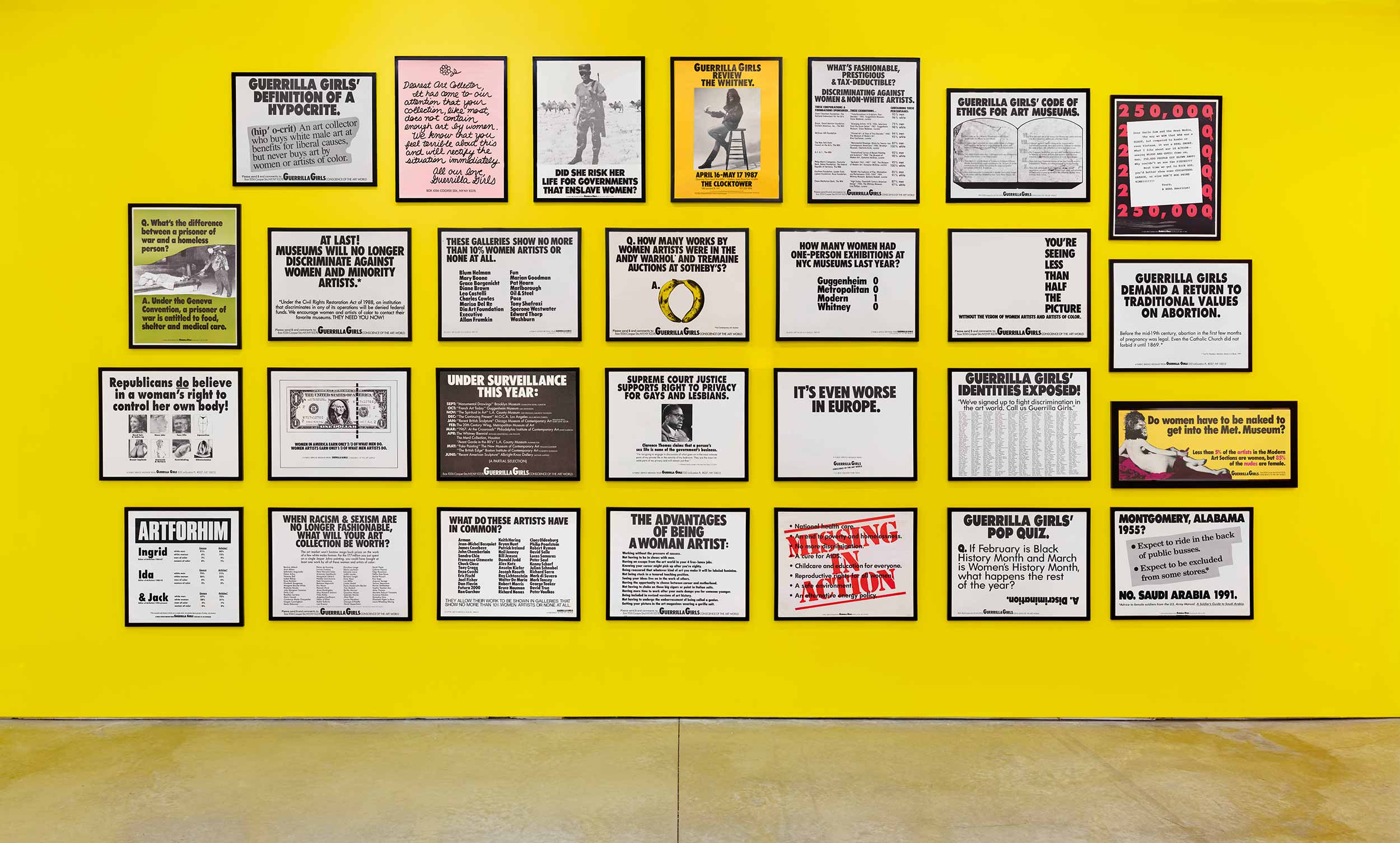

At Hannah Traore Gallery and in a back room at Mary Ryan Gallery, one can see the polemical work of the Guerrilla Girls and find the radical artistic propaganda that predates modern feminist groups like Pussy Riot. The two factions both share a love for masks; the Guerrilla Girls donned gorilla masks while Pussy Riot primarily donned neon pink balaclavas. “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” is one of the Guerrilla Girls’s most infamous pieces, a ferocious poster featuring a naked woman in an ape mask.

Can such beautiful art be political? Does it offer something beyond the reflective surface?

Stevens was often trying to reconcile her ideas of beauty with activism. In a lesser-known work of poetry she wrote, “No politics without poetry. No poetry without politics.” A refusal to make such sacrifices animates a new retrospective of her later work now on display at Ryan Lee Gallery. A new exhibit titled When the Waters Break focuses on a series of paintings and lithographs made after her involvement with ground-breaking feminist guilds. Violence haunts the work. Tiny asemic writing glistens in silver and gold across lyrical, wistful landscapes. The text is almost impossible to make out, though we are told in the exhibition that it’s composed of words appropriated from Virginia Woolf and Julia Kristeva, two of Stevens’ primary influences.

While Stevens’s infamous portraits of Rosa Luxemburg, her bigoted father, or Jewish husband whose parents were killed by Nazis aren’t present, her seascapes remain scarred by such brutal memories. Water moves. Luxembourg was drowned. Stevens scattered her husband’s ashes in rivers with her friend the art critic Lucy Lippard. Grief can wash away, but the river always recycles our memories. Can such beautiful art be political? Does it offer something beyond the reflective surface?

“The personal is the political only if you make it so,” Stevens once wrote in an essay titled “What Kind of Socialist-Feminist Artist Am I?” Certainly, her painting This is Not Landscape (2004) feels like a challenge to the status quo of male abstract expressionist artists. At one point, Stevens was allegedly told by an art critic that she couldn’t make something that wasn’t a landscape even if she tried. The result is a drippy powder blue Rothko-like work of abstraction on unstretched canvas. It’s a curious provocation to invoke considering that Stevens had many distinct periods of work: Pop Art-inspired depictions of cops and her fellow women artists, paintings that situated her mother next to Rosa Luxemburg on flat planes of green and blue, and her depictions of the Freedom Riders in black and white. Only later in life did she seem to succumb to lyrical abstraction. But even this is a deceptive framing of Stevens’s paintings.

The violet-tinged blood red of Boat at Rest (2003) and the nauseous green of River Run (1994) both evoke something larger than simple pastorals. Into the Night (2009), Stevens’s alleged last work, summons the finality of teal and viridian waves enclosing a lone woman on a boat, words rippling in her white wake. Politics is not just the loud stratagems of socialism or theory.

If we zero in on only labeling certain kinds of work “political,” what do we lose? This is not to say these late paintings of May Stevens are a “protest.” That’s certainly reductive and a mislabeling. But it is to say we should open up the horizon of what we consider canonically “feminist” art.

Solitude can be just as strong a statement as totemic posters, stickers, and flyers. Hannah Traore Gallery states in their exhibition text for “Discrimi-NATION” that it’s important to include the work of the Guerrilla Girls in galleries. Propaganda too can be art. Perhaps the inverse can be true too. Think of the iconoclast feminist intellectual Shulamith Firestone. Her final work was a novel about the psych ward, not a polemic, yet it has things to teach us all the same. Often the Second Wave feminists and artists we think of are the loudest–the ones who grabbed our attention with their tracts and noise and frenzied yonic imagery.

The collaboration of the Guerrilla Girls and the art publication Heresies are both key examples of feminist cooperation. Such groups made sure to privilege the visibility of women artists. It is important to look at the overlooked—they may offer new ways of considering art and praxis in the coming days. Plenty disagree. Many think if art is less political, it is simply watered-down navel-gazing. I’m not so sure. Of course, good politics are important. I care more about what someone does behind the scenes and in the modes of production than just how militant the content of their work is.

The legacies of feminist art and practice are not only to be found in the overt artwork of the Guerrilla Girls, but in the archival quiet gasps and cries of women artists whose work went against the grain all the same. The beautiful brown-green palette of Sometimes the sun the moon (2005) is a feral image of land meeting water, ground meeting sky, moon meeting sun. Boundaries dissolve in umber, taupe, auburn, and chestnut. Stevens’s command of color and brushstroke are stunning. While the zeitgeist ferocity of the Guerrilla Girls continues to speak to our political moment, the work of May Stevens provides a different kind of antidote. Even her visions of nature elucidate an arresting perception of justice.

May Stevens, When the Waters Break is on view at Ryan Lee Gallery until April 12.

Guerrilla Girls Original Posters 1985-1994 is also on view at Mary Ryan Gallery until April 12.