Recently on view at Bridget Donahue, the Queens-born artist's solo exhibition is a multimedia intervention on broken dreams and the taxi medallion crisis

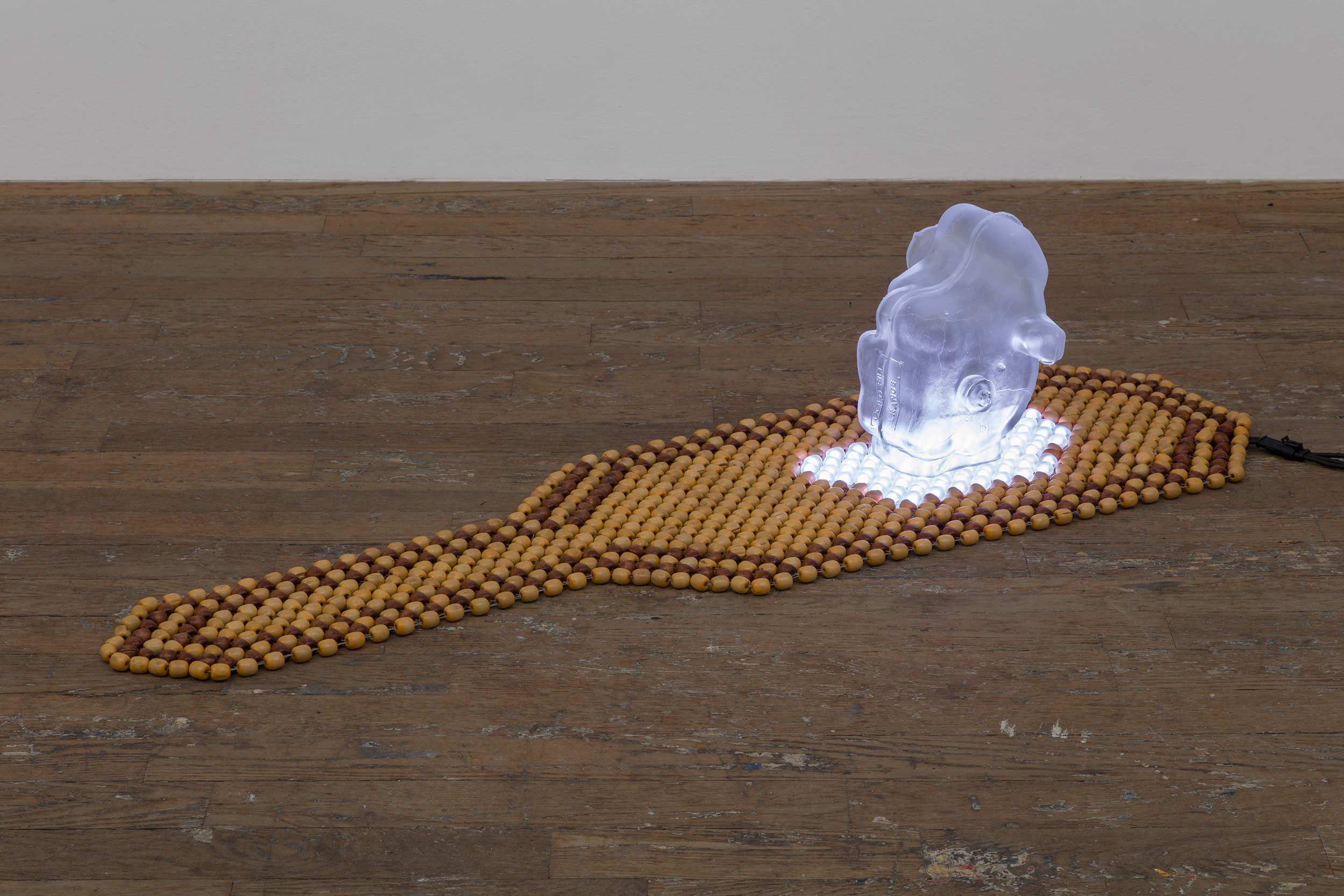

When I walked into Kenneth Tam’s exhibition The Medallion at Bridget Donahue, I first noticed how careful my steps were, and how aware of them I was. The gallery floor was transformed by Tam, now blanketed with approximately 370 beaded mats, each made from 1,000 wooden beads. The mats were driver seat covers found in New York City yellow cabs. Nowadays, cab drivers, who are often South Asian immigrants, install the seat covers to alleviate the physical discomfort of prolonged seating. At the gallery, to endure visitors’ footsteps, the beaded mats are tightly compacted, yet arranged loosely enough that each bead can still move under visitors’ shoes. I quickly learned how my steps created reverberations and aftershocks, adjusting my footfalls accordingly. “Be mindful,” I thought to myself. “No stomping.” Exactly as one does at a scene of ruins.

The Medallion is more than an exhibit, it is a story about the circulation of the taxi medallion—a costly permit issued by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission that gives a driver the right to legally operate a yellow taxi in New York City. The story is a tragic one. Though he is now based in Houston, Tam is originally from Queens, home to many of the immigrant drivers caught up in economic nightmares caused by medallions. Tam speaks near his subject, maintaining a critical distance between how drivers’ lives unraveled and viewers’ desire for knowing more. The exhibition staged a scenography of appropriated and reproduced car parts that reference the story of affected drivers by proxy. For those unfamiliar, here is how the story goes: many immigrant taxi drivers signed exploitative loan contracts to purchase medallions which are in limited supply and assumed to appreciate in value over time. However, when ride-sharing apps such as Uber and Lyft came along, profit margins in the taxi business dwindled, curtailing drivers’ loan repayment ability and depreciating the value of medallions. Now, the medallion, once a symbol of class aspiration and mobility, has become a lethal burden, drowning many taxi drivers in severe debt, forcing them to declare bankruptcy. Some even died by suicide.

At Tam’s exhibit, the most direct intervention into the heart of the tragedy is the eponymous two-channel video installation, its footage projected onto two opposite sides of gallery walls. The footage on one channel projects close-ups of actual taxi drivers narrating their own despair after falling victim to the medallion scheme, yet vowing to face the financial ruin head-on. There is an insistence on naturalism by the camera, positioned in the passenger seat next to the driver, creating emotional closeness with him. Curiously, this part of the footage leaves out biographical accounts of the drivers’ initial participation in the medallion trading scheme, instead centering confessionals in its unraveling aftermath, a notable deviation from the genre conventions of oral history and documentary. The other channel of footage consists of three anonymous bodies, presumably taxi drivers, engaging in loosely choreographed, constricted movements underwater, followed by each person in a dilapidated room conducting slightly awkward movements that reference spiritual gestures of humility and submission. Toward the end of the footage, all three drivers come together in a circle shoulder to shoulder, locking hands to perform semi-ritualistic movements of fraternal intimacy and solidarity. In the movement-based footage, the camera refrains from zooming into facial expressions or specific zones of the moving body, favoring overviews. The footage’s cyclical order suggests an absence of linear narrative. The two streams of footage run in parallel to each other, at times swapping sides arbitrarily, their timestamps never in sync, leaving short gaps where a driver monopolizes viewers’ attention on one wall while the other is blank. The video is an expansive presentation of grief and its working-through, where a future foreclosed by financial ruin can be temporarily retrieved in these embodied fantasies. An elegy does not need to believe in the finality of death.

On the gallery floor, Tam used car parts to evoke the aftershock of a car crash. Some of the parts were appropriated, others were printed or cast. It is no use to worry (coolant overflow) (all works 2025) and It is no use to worry (expansion reservoir) use sleek, pristine hand-blown glass and 3D-printing to simulate the mechanical parts referenced in the artwork titles while It is no use to worry (radiator reservoir) and It is no use to worry (prayer wheel) appropriate said objects. Underlit by clinical LED lights, the parts feel haunted by their prior owners.

Collision presents an imagined aftermath of a car accident. An abandoned ashtray and gold retirement watch allude to the ghost of lived life now perished. A few epoxy resin LED lights still glow dimly, while others are completely off. For Tam and the drivers, a financial crash and a car crash are analogous.

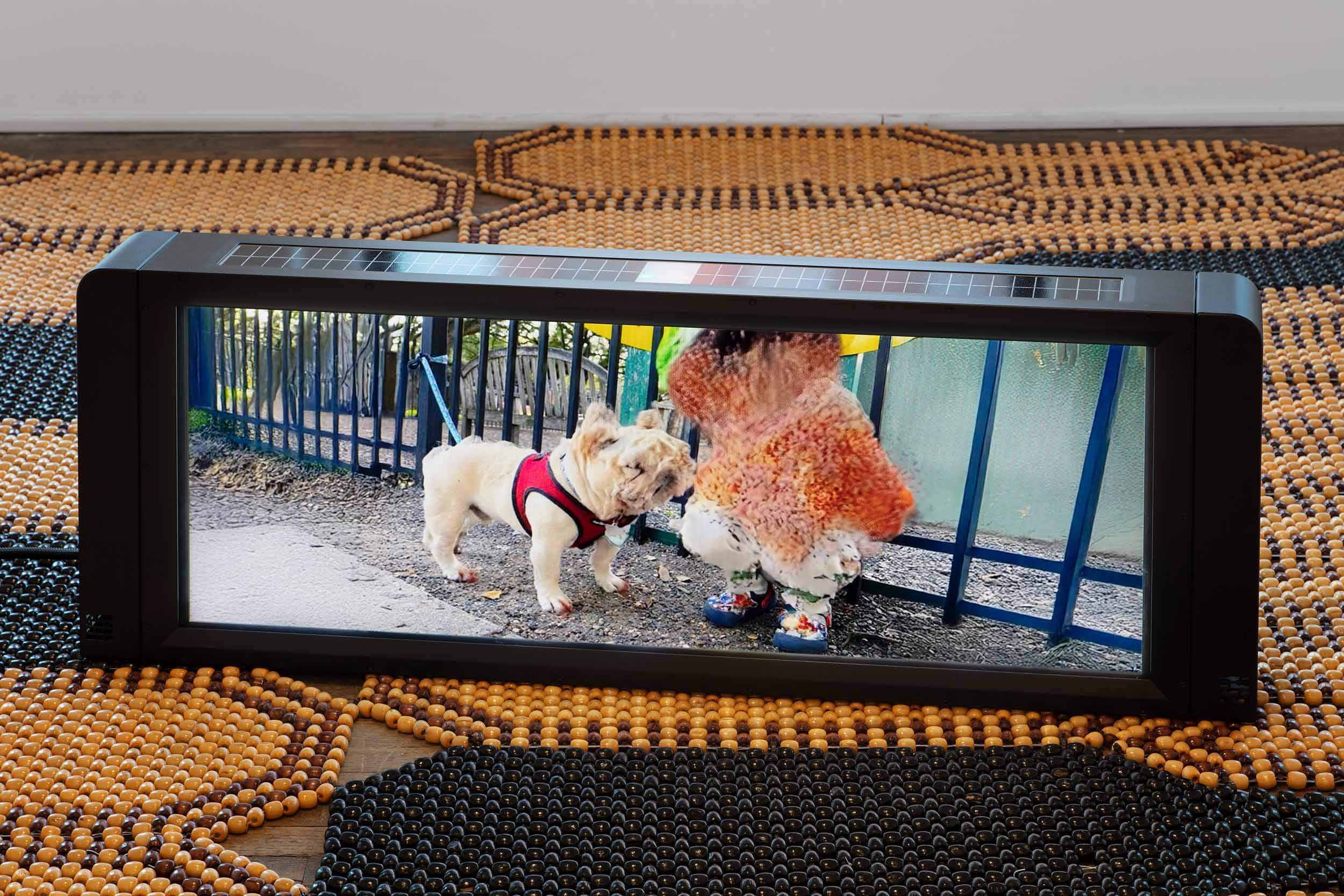

A work least related to the theme of the taxi medallion scheme, Dissolved personal archive (2015 – 2024), stands out to me. An appropriated taxi top video display, the screens on the roofs of taxis that usually run ads for Broadway shows, plays silent AI-generated videos. In them, amid the familiar setting of the artist’s studio or museum solo show, objects, animals, and people disintegrate into molecules and then disappear like dust in the wind. The video feels absurd when it’s of an everyday object, and abject when it’s of a person. Ten years of reimagined life condensed into an eight-minute video that ends in absolute nothingness.

In The Medallion, nothing lasts forever, and ghosts linger. Tam circles around the infrastructure of precarity and the liquidation of life in neoliberal America, with a poetic sensitivity to hope in spite of it all, and a resolute commitment to saying it as it is. Refusing to represent loss as an abstract concept, Tam grounds it in everyday life and the people that had dreamed of a different course. The future is not exactly bright, but its bleakness still must be described.