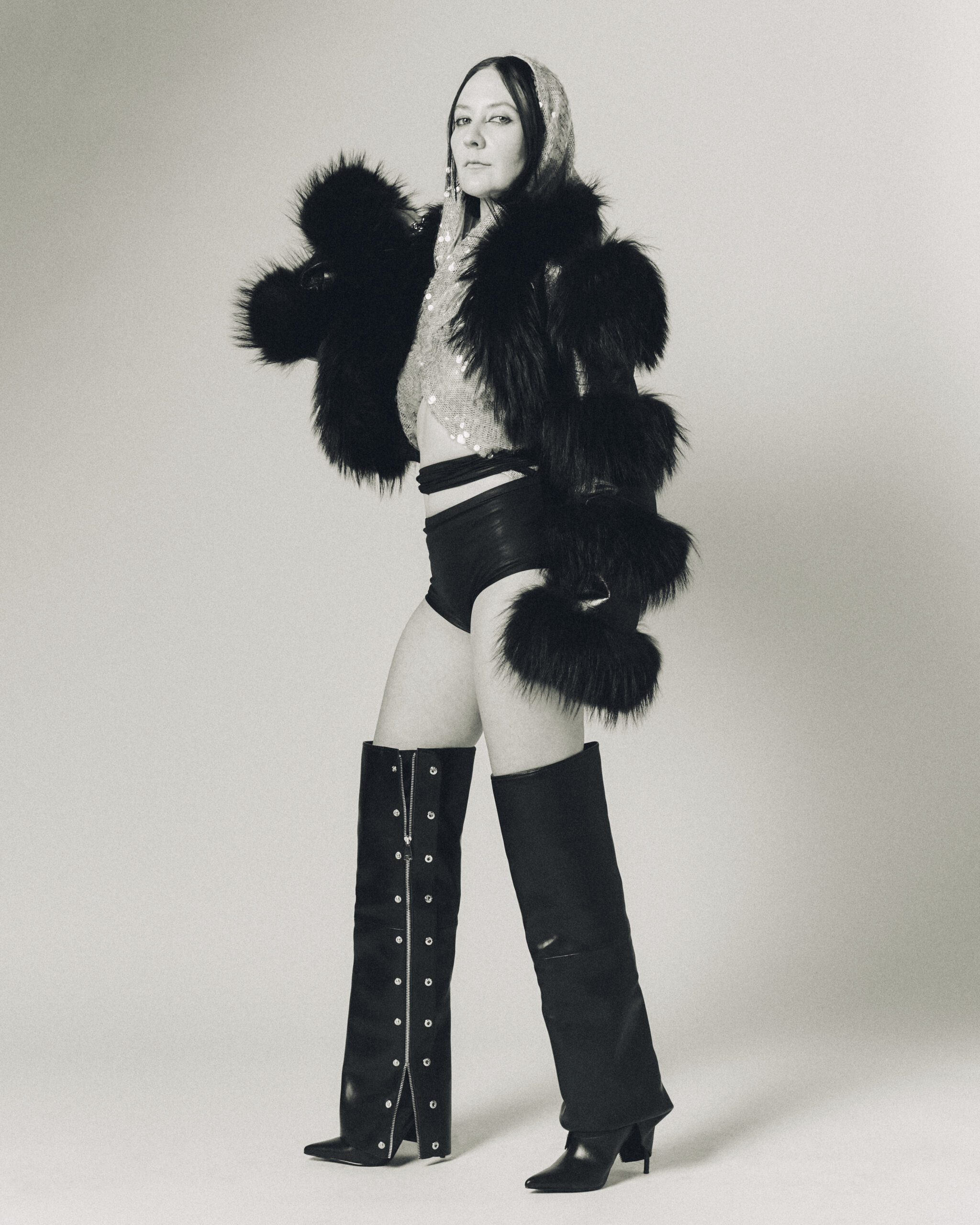

The Brooklyn-based artist contemplates energy and momentum in her newest album, 'Gut Ccheck'

Kinlaw’s second album Gut Ccheck thrusts listeners into a high-momentum sonic flow. The New York City-based, North Carolina-born multidisciplinary artist and musician pushes the boundaries between sound, movement, and visuals— guided by an intuition more interested in modes of connection than pre-set disciplines.

Releasing March 21, the fourteen tracks of Gut Ccheck oscillate between the dreamlike, the pulsing, the psychological, and the concrete. The album is conceived with a drive for momentum, and tracks including “Ride the Ride” and debut single “Hard Cut” urge listeners to harness energy, and pursue scrappy or alternative means of possibility and actualization.

Kinlaw’s background is rooted heavily in choreography, performance art, and collaboration. In 2016, she co-directed the interactive installation and dance production Authority Figure at Knockdown Center, inaugurating the space as the culture and arts hub it has now become. In presenting projects at spaces including MoMA PS1, Pioneer Works, and The New Museum, she maintains keen awareness of connections between performance, audience, sound, and space – one time sitting in every chair before a performance, attuning herself with each audience member’s experience. Gut Ccheck was developed, in part, during a year-long residency at Bell Labs historic Anechoic Chamber, where Kinlaw conducted research in what was once considered the quietest room on earth. Certain sounds on the album are conceived through physical gestures – the motion of crawling on the floor during a moment of frustration making way for a unique sonic experience. Gut Ccheck is co-produced by Carlos Hernandez.

Kinlaw sits down with Document to discuss alternative ways of working, the coming into one’s own voice, and the artist’s consistent return to “The Handshake” – the place wherein the audience and the art understand one another.

Chloe: The sound with Gut Ccheck is pretty different from your first album, The Tipping Scale. How have your sound and ideas evolved from your first album to this one?

Kinlaw: The first differentiation that comes to mind is that this album is written less from the head. It’s written less from an overwhelmed place, and more from a curious place. When someone is overwhelmed, it’s hard to think about much of anything other than yourself, whereas now I think I have much more of a technical curiosity, much more of a storytelling that roves around.

Chloe: That segues into choreography and performance and your process of writing and music. Do you feel like each of these practices exist as independent mediums for you, or when you’re doing one, are you considering the way that it interacts with the others?

Kinlaw: I’ve made a practice that obliterates the categories. It’s important for me to do that. I think that what we call inter- or multi-disciplinary is just a pretty intuitive way that I work and that perhaps a lot of other people work too. I learned how to be a performer, and how to be an artist, by playing in bands.

Now, I have much more of an interest in architecture and space. I have a curiosity. I’m obsessed with permits and permitting—you know, what can you get away with? I just did a performance in a two tiered parking structure in Soho that I had walked past so many times, and I was able to work it out with them directly to perform there without a permit. It was so exciting, and it was so fresh-feeling to me, and that’s the feeling that I’m chasing. I think there are a lot of practices in the music world especially that aren’t ethical or fair towards the artist, and so I am trying to figure my way around a system that I don’t like. I’m really curious about making this form sustainable and fair to me, to other people, and also fair to my audience.

Chloe: What about the residency at Bell Labs? How has that has led you to this new album and where you are now?

Kinlaw: The thing about me is I’m gonna weasel my way into what I want. I think this is a kind of cool connection to what you’re talking about in terms of interdisciplinary working. I was able to get full access to this anechoic chamber, which was once the quietest room on the planet. This was extremely interesting to me, because I’m not only curious about how to create sound, but I’m also curious about how we hear and how our body plays a role in how we receive music, sound performance, all of this. There’s no better place to think about psycho-acoustics than this particular place, in this particular room. What was supposed to be a shorter stay turned into two years of consistent visits, and really informed a lot of my approach to making this second album.

Chloe: What’s it like being in that room? Can you feel the silence viscerally?

Kinlaw: I mean, that’s the whole thing. You have to, at first, take it slow. It’s pretty normal to have a panic response, or an anxious response, or just to have auditory hallucinations. When sound is taken away from you completely, and there’s no reverberation, your response is to create it, meaning some people hear their name, or they’ll hear a sentence.

I embraced a lot of the sensations. I had to reacquaint myself with complete silence and then, really, really, deep listening. That kind of experience is an honor, and I need to continue research like in the anechoic chamber in order to make the work that I want to make. A big, big part of my curiosity as an artist is just recognizing that I don’t know everything I need to know and that I want to learn and that I deserve to learn.

Chloe: That sounds uncannily connected to the way you’re describing how you work with sound and choreography.

Kinlaw: It’s essential to remember or be reminded that I’m working within a system, and that system is automatic. When I step up to do anything, there’s already something happening, before I make a sound or before I make a gesture. And also, on the other end, I think an equal part about the viewer and the audience as I do [about] my perspective, or what I’m making. I call it a handshake, sometimes: that middle ground is where we meet. I can create a show or I can create an album, and someone can be there to listen and to receive it. The handshake is where we get each other—or where we don’t—but I think lately we’ve been getting each other, so it’s been fab.

Chloe: What do you hope that audiences can receive with this new album?

Kinlaw: I don’t make anything thinking about how it will be received at first. I can’t. But, I hope that this work gives people permission. There’s a lot right now that’s working against creative people, people who are lower income, people who you don’t identify as the straight and narrow. A big part of being an artist now is making it work for you, and a huge part of my mission is to make those possibilities available to other people. Like you’re saying, I want people to put on their headphones and walk through the city and listen to ‘Hard Cut’ and feel this kind of gut confidence in their stomach, or to do something new, or to surprise themself.

Chloe: You have these really strong, powerful titles, like ‘What You Own Owns You’ and ‘Ride the Ride’ and ‘Vile on the Couch’. How do you come to that? And more generally, how are you coming to language?

Kinlaw: The titles were last. They came after I had done a lot of thinking and sitting with the material. I think of titles as little homes that can be either in direct conversation with the material, or in opposition to the material. In any case, the intention is to give a word to help people go deeper. I’m really quick to speak about pivots and what I do to just keep going. The real work is when you have run out of ideas, and I’m pretty quick to disclose that. I’m pretty quick to be like, this part was really hard. I was desperate, I was crawling. But I also think that that’s sick, because I have so much clarity in what I’m looking for that I won’t accept when it’s not totally the thing. I wait until I find my anchor.

Chloe: You’re from North Carolina. How have North Carolina/your home state and New York City influenced your work?

Kinlaw: The record opens with my dad talking. He says, ‘What you own owns you.’ He is so Southern, I think over half of people who listen won’t be able to even understand what he’s saying—which is also part of why it’s in there. I am constantly in awe and also in conflict between the life that I have here, and what I come from. I am angered by the treatment that my family has received in the past, I’m angered at the lack of resources that they have, the lack of opportunity, the lack of support my mom, who’s been disabled my whole life, has received. I see so much opportunity here and I straddle a kind of interesting position. It’s a conflict. I still feel like I am this North Carolina punk. And that’s part of why I am persistent, and that’s why I’m so resilient and always chasing new forms. I don’t know why I have so much belief that things can be better than they are, but I’m not going to question that because it’s a driving force.

Chloe: I’ve had conversations about how there’s a kind of inner tug when you’re doing experimental research intensive projects. You want the research to deepen the work, but you don’t want opacity and conceptualization to become this barrier of entry. It sounds like you navigate this, and you cut to the root of things.

Kinlaw: And I can’t do it if it’s not fun. That is another part of what I just provide for myself, and I think a big reason why I’ve been able to have such a long practice. When I’m having fun, that’s when I’m the most loose, that’s when I’m able to see people there. This whole campaign is so much about just doing things on the fly, going with momentum. Imperfections are okay, typos are okay, which is actually why the album title is what it is with the two C’s. I’m actively pushing back against planning too much, and over rehearsing.

Chloe: Feedback is a recurring motif in your work. What does feedback mean for you? How do you use the interaction between sound and space to shape your compositions?

Kinlaw: Feedback is chaotic and it’s difficult to control. Feedback is also a response to a room. It is a reflection of proximity, distance, and space. I mean sound and space, they’re just always talking to each other. They’re hand in hand when you’re interested in what performance can be. You think about how things sound in space, how light changes the space, and for me, I often think about how close or how far away I am from the people who are there. It’s been a decade-long thing I’ve noticed: how I respond to different rooms, even just as a person, not as a performer. A lot of the ways that I approach art making comes from how I walk around in the world trying to notice how spaces change me, particularly as someone who is prone to feeling shy. I have an interest and a love for painting a room with sound, but also I can let it go and do what I need to do, because that’s what performing asks of you. I have to remain flexible. There’s a time for study, there’s a time for research, and there’s time for presetting—and then there’s also a time to just let it go.

Creative Director Kathleen Dycaico. Photo Assistant Fabio Utrilla. Stylist Assistant Caden Swift. Make-up Artist Tayler Treadwell. Hair Taichi Saito. Production Statement Of, Polymath Production. Lead Producers, EP Hannah Kinlaw, Cameron Sczempka.