On view at Management Gallery, the painter’s latest solo show presents a not-so-far-off future obsessed with spectacle, where nostalgic glamor and necrosis entwine

Now you know the scene

Your skin starts turning green

Your eyes no longer seeing

Life’s reality

Push the needle in,

Face death’s sickly grin

Holes are in your skin,

Caused by deadly pin.

—Black Sabbath, “Hand of Doom”

When I first saw Tim Brawner’s painting Kay—a smoky, golden scene of a picture-perfect Old Fashioned, with a disembodied, fully muscular yet somehow mummified and charred hand tenderly placing a crystalline ice cube into the glass—Black Sabbath’s “Hand of Doom” started playing in my mind. And for a painting to conjure the heavy metal gods, you know it’s gotta be good.

Released in 1970 (the year the internet says “postwar art” ended) through Vertigo Records, Black Sabbath’s Paranoid—a cornerstone album within metal canon containing bangers like “Electric Funeral” and “War Pigs” along with its title track—also features “Hand of Doom,” a sickly lament reflecting the pain and fear the band witnessed as soldiers returned from Vietnam spiritually crippled, emotionally obliterated, and, for many, drug addicted. The Vietnam War, the first to be televised, lasted until 1975.

Nearly 50 years later, this spectacle of war might serve as an origin story for the post-postwar fucked-upness of today’s media-saturated realities and the addictive nature of witnessing trauma through a screen, both of which echo within Brawner’s solo exhibition The Last Caress, on view through February 23 at Management Gallery. In the eight-painting show, Brawner’s disquietingly yet comfortingly disturbing paintings, complete with nods to a bygone era of Hollywood glamor, pulse with anxiety and reflect our contemporary instinct to rubberneck at the lives of others. They produce a dire, dissociative gaze—seducing an eye and heart hardened by inundation, leaving little room to feel, only to watch—mirroring a larger cultural condition of numbed detachment.

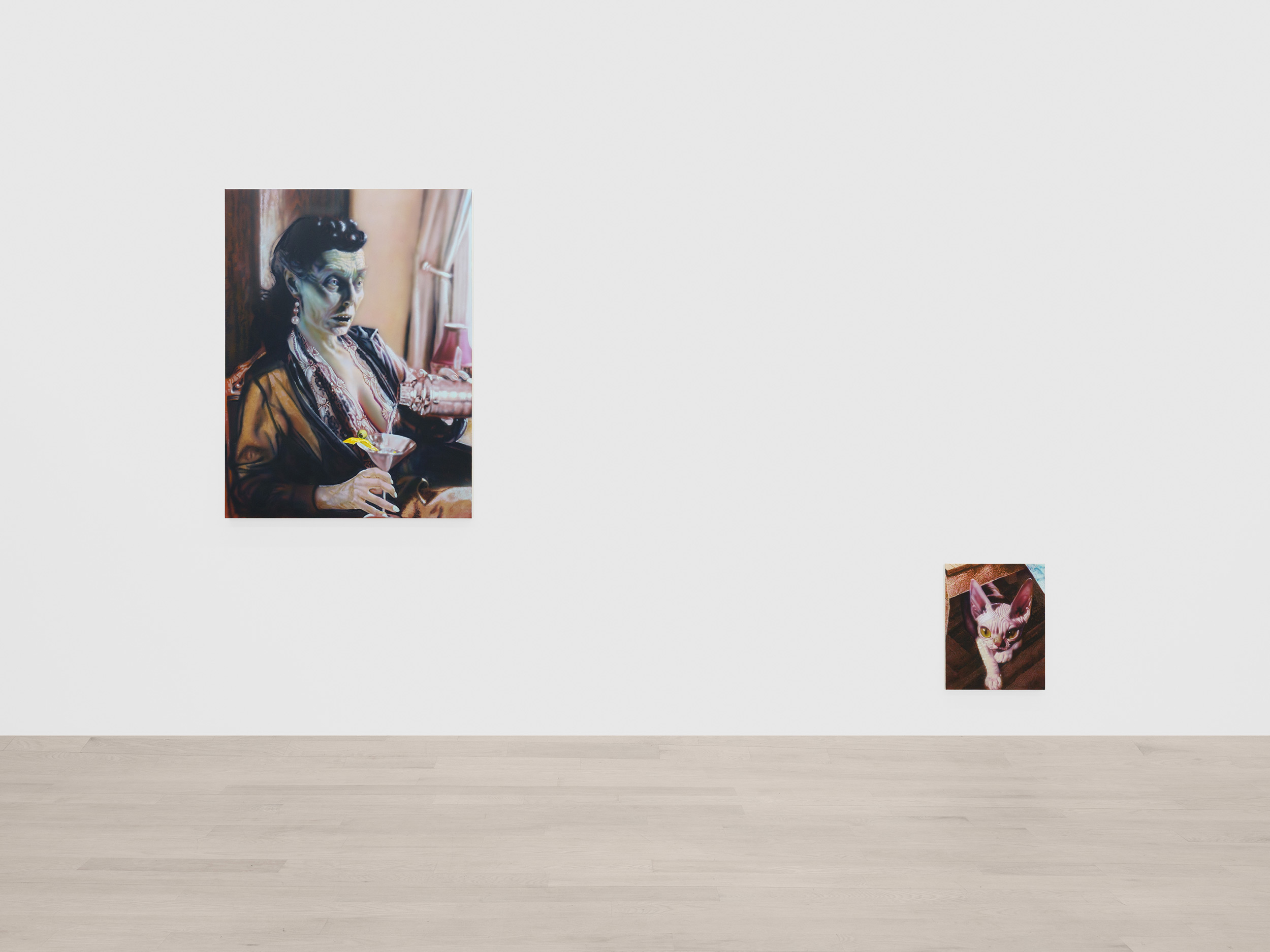

Like his previous work, this new series explores figuration through nightmarish psychic imagery. But what is most exciting with The Last Caress is how the artist continues to expand his focus to include more human (or human-like) forms: think zombie-meets-movie star. The figures, all of whom appear to be white women (aside from a menacingly cute cat in Ichy) are pictured as necrosing, gnarled, or corrupted. While body horror is in vogue in contemporary art, Brawner pushes it further with finesse and subtlety in these works.

Take Sybil, where we find ourselves at the ground level of a hideous car crash—flames erupting, a woman’s skin seemingly burning as she stares into the crash, and another woman’s body lying in delicately mangled repose, her ankle just so tenderly broken. Despite the horror, Brawner threads beauty through the wreckage: a disembodied tire resting beside a black pool of slick oil and the jeans of the presumably dead woman with the broken ankle are encrusted with shimmering white dots of paint like sugar crystals topping off a confection.

What’s so jarring about Sybil is how precisely it captures an all-too-common stance: we, me, you, watching from a dazed distance as someone else watches a disaster unfold before them. Like a passive observer holding a camera, bedazzled and confused by the violence of living, Brawner positions the viewer as numbed, incapable of offering help. This haunting distance reflects the cultural drift toward detachment that so many are experiencing.

The act of watching, witnessing, and consuming is further explored in Harlow, a movie poster-sized painting at 3 by 4 feet, named after Jean Harlow, the pre-Code sex symbol and American movie star known as the “Blonde Bombshell.” Though a prolific icon in the 1930s, Harlow was also America’s heartbreak. She died at just 26 from treatable illnesses that were largely ignored until her declining health delayed film production enough to warrant intervention. Stars like Harlow epitomized a more untamed kind of Hollywood glamor. But here, Brawner presents a vision of her writhing in pain, her flesh nearly melting off as she smokes a cigarette at her boudoir.

Brawner’s portrayal of Harlow is at least double-edged. Is this an image of the physiological and psychological toll of objectification, or a lament for a bygone era of the high-femme diva? The painting resists a clear answer. Similarly, the boudoir serves as both her stage and her tomb. Brawner has embellished the frame (or is it fame) so heavily that the distinction between decoration and decay collapses—the soft focus, which reads almost like mold, is punctuated by crisp pustules of white paint popping in the spotlight. There’s a filmic quality to Harlow, as if painted on degraded 70mm film, the reel burning as it rolls, capturing a psychic collapse. After all, perhaps the most defining quality of a star is not just that it shines hot, but that it eventually burns to death.

In Harlow’s pained expression, I see a life of pins and holes reflected back. I’m no glamor girl, but this painting makes me wonder: how do we meet our own gaze these days, having been exposed to mass death on the reg, live leaks of beheadings, and trauma, trauma, trauma? I write flippantly because—hasn’t it all just become that casual? Through this melting reflection, which conjures another Sabbath lyric—“Dying world of radiation. Victims of man’s frustration” from “Electric Funeral”—Brawner offers not just a cinematic depiction of quotidian decay but also a critique of glamour and the systems that circulate its ideals: film, media, celebrity culture.

Trivia and Lynn follow a similar tone—both depicting glamorous yet gangrenous women gazing out a window, pausing for a moment’s respite in libations while, presumably, the world burns just out of view. Both paintings are scaled so that the figures feel eerily proportional to the viewer, placing us in direct relation to them. In Lynn, a woman draped in a luscious fur coat, chains of diamonds, and a single oversized pearl earring is rendered in the color of severely concentrated urine. She delicately holds a cup of tea. Trivia, by contrast, is cast in the blue-green hues of oxygen-starved veins—her skin cold and cadaverous. Wearing lace and a sheer top, she pours herself a dirty martini with a twist.

Decay seeps into the environment; simple shapes, objects, and materials like cloth appear to be rotting, yet they glisten in the last light like remnants of burning petrol. This level of detail—this slow, sumptuous degradation—is often overlooked among Brawner’s creature-feature peers. There’s something deeply unsettling in the way he frames these women, where the power of beauty is inseparable from their doom. I can’t help but suspect a subtle inquiry into the ongoing socio-political demonization of women, not as life-givers, but as withholders of life; death-dealers, as America’s right-wing seems to have framed women as of late. Unironically, the topic of female autonomy in relation to healthcare and sexuality was one of the most contentious aspects of film censorship in the 20th century.

Brawner goes beyond just the body and its depiction. By aestheticizing the corrosion of everyday life—where in Layle, driving becomes a terrifying act, or in Kay, a bartender’s hand is rendered gangrenous—Brawner pulls viewers further into a dissociative gaze. Part of me truly believes we’ve become so unfazed that if a necrosing hand passed you a drink, you’d just sigh and ask for another.

And so, it seems that many of us are no longer participants in life, or even witnesses, but subdued, passive observers in a world where life—either our own or someone else’s—appears to rot as it flickers past in the blink of an eye. I return to Layle, where Brawner positions us on the dashboard of a car, looking up at the driver—a woman whose jaundiced yellow eyes, tinged by liver damage or the blaring headlights of an oncoming vehicle, radiate pure terror. Her face is frozen, as if she’s watching her life flash before her eyes in the moments before an imminent crash.

And so, what are we watching? We watch her watching her own demise.

What first drew me to Brawner’s work is how he exemplifies strong, skilled painting in a contemporary landscape where lazy approaches too often reign. I’ve barely touched on the technical skills here, that’s something you need to feel with your flesh. But ultimately, it’s how Brawner advances the creature-feature, body-horror genre that stands out the most to me—embedding grotesque distortions into the very atomic structures of the environment itself.

Now to circle back to Vietnam. I’ve been thinking a lot about postwar art, with its elongated, ghastly figures isolated or merged in an atmospheric haze. As a genre marking time, it makes sense; as an art form, it feels like an appropriate response to witnessing the horrors of war. But what’s so obviously lacking in that term is the “post”—as if we, societally, have moved past war. If anything, we are either unfortunate enough to live through war or, at the very least, fortunate enough to live alongside it. Brawner understands this, but how do we talk about art made in this state of perpetual war? Steeped in cinematic research, the theatrics of the living, and the ghastly horror of the dead (or dying), his paintings exemplify what I’d like to call perpetual war art—the result of constant inundation by pins and pixels. It offers us the banal but queered through a glistening, totalizing doom. A more subtle, sinister decay that gnaws at everything, even as it’s being taken away. So, Whatcha gonna do?

Time’s caught up with you

Now you wait your turn

You know there’s no return

Take your written rules

You join the other fools

Turn to something new

Now it’s killing you.

—Black Sabbath, “Hand of Doom”