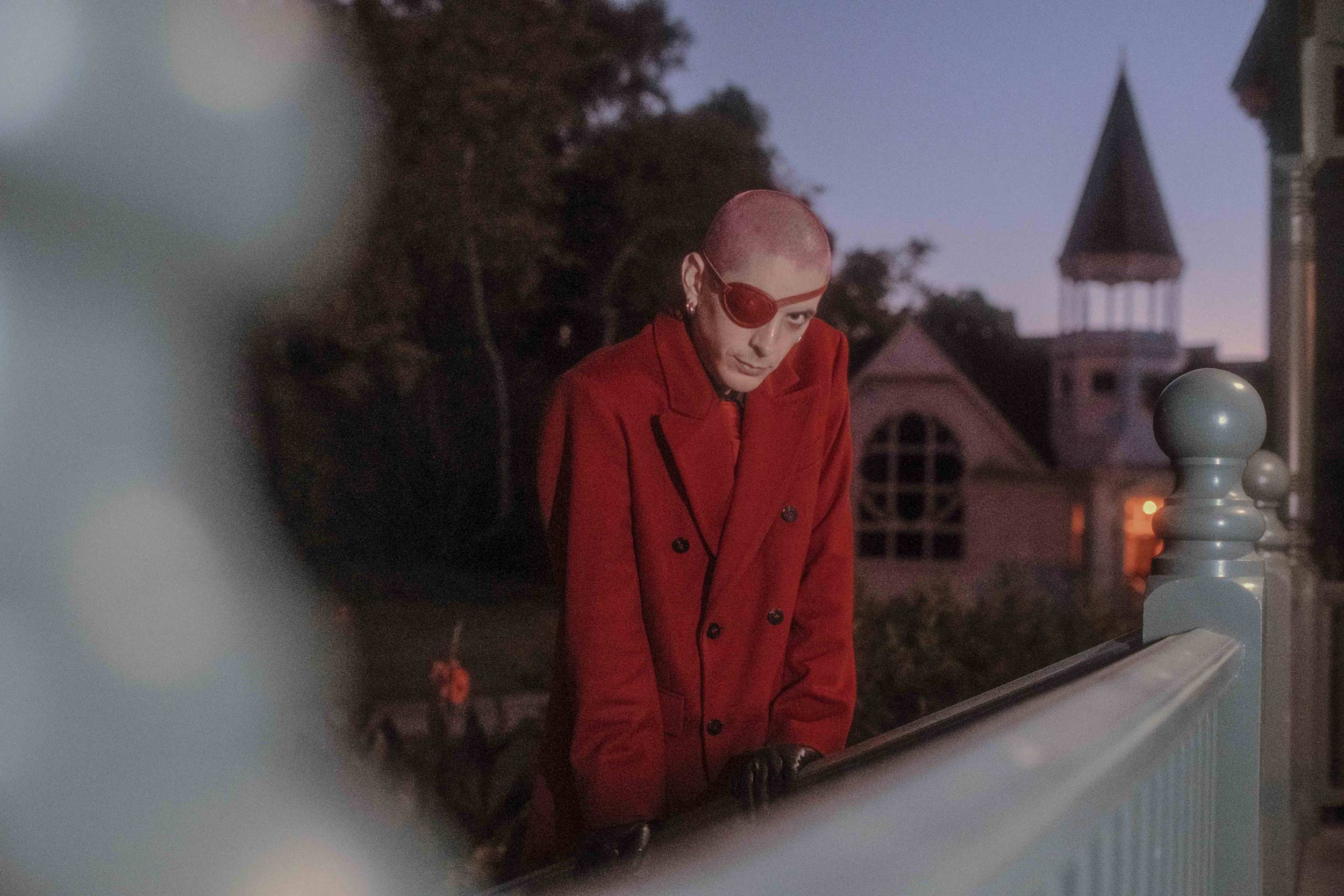

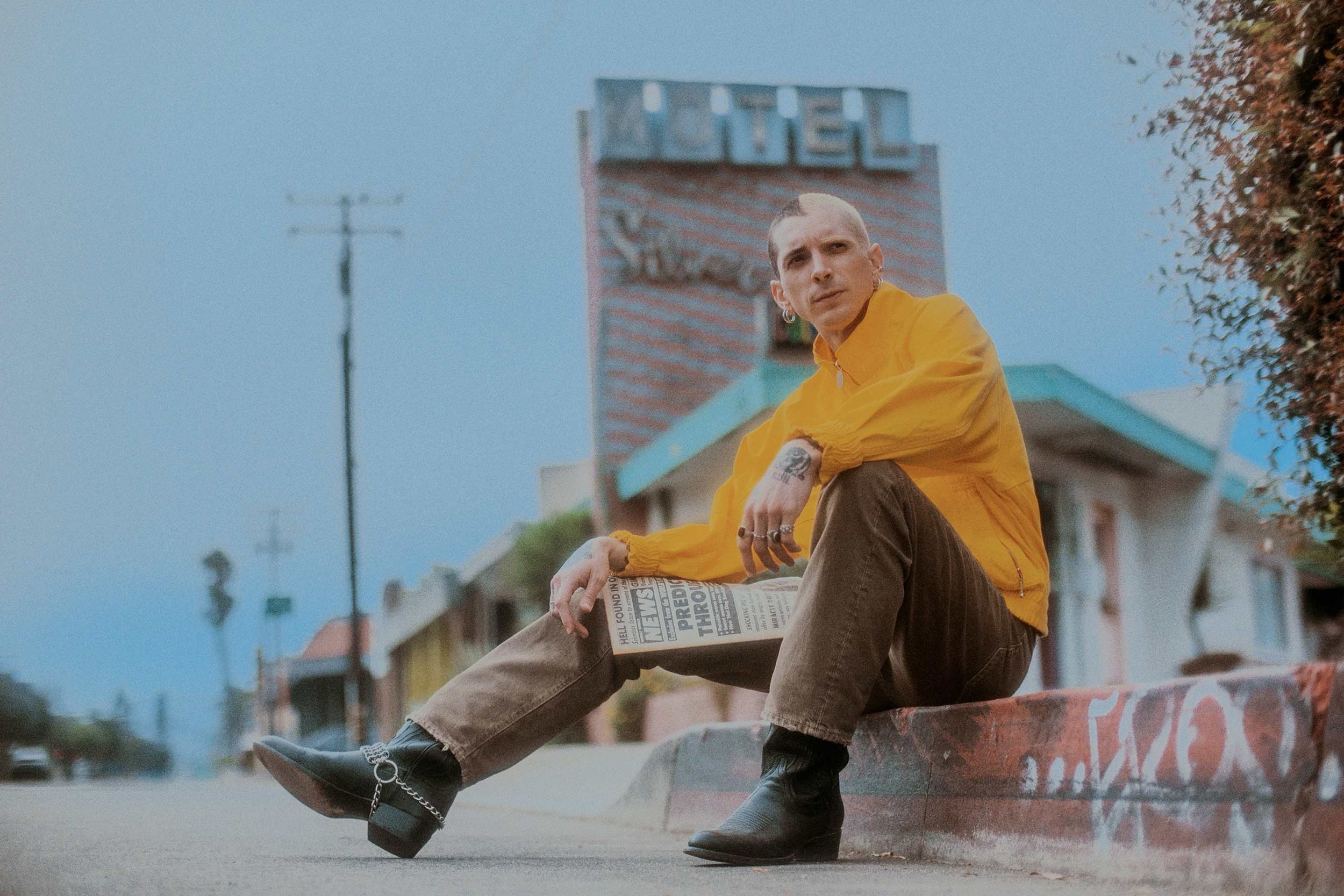

Trevor Powers aka Youth Lagoon sits down with Document to discuss how the full spectrum of human emotion might emerge on a record upon the release of his fifth studio album

For over a decade, Trevor Powers—better known as Youth Lagoon—has crafted music that feels like a waking dream. From the bedroom-pop intimacy of The Year of Hibernation to the sprawling, cinematic textures of Heaven Is a Junkyard, his work has always balanced hope with unsettling undercurrents, be they memories, or suppressed emotions. On Rarely Do I Dream, the artist’s fifth studio album with Fat Possum Records, Powers uses soundscapes to examine himself from an outside perspective, coming to the powerful conclusion that nostalgia doesn’t mean as much as learning from it. Rooted in deep meditation and shaped by personal upheaval, the album explores the fluid nature of memory, perception, and reality itself.

The title, Powers explains, was born from a period of transformation. As he deepened his meditation practice, the line between awake and asleep blurred, reshaping his understanding of existence. This shift wasn’t just philosophical—it profoundly impacted his creative process, inspiring a focus on being rather than doing, he says. That approach makes Rarely Do I Dream his most emotionally raw yet.

Sonically, the album continues a delicate blend of warmth and unease, a Youth Lagoon signature sound created through sparkly synths and lurid basslines. Home videos from Powers’ childhood inspired its themes, but rather than indulging in nostalgia, he uses them to reveal deeper truths, what’s left unsaid, what the camera didn’t capture. In his words, “My job was to weave the full picture, the warmth and the darkness, because truth is always in between.” The result is a record that feels like a living memory: shifting, complex, and undeniably human.

Powers sits down with Document to discuss his unique approach to building feeling in sound on Rarely Do I Dream, the complexities of the full spectrum of human emotion, and how nostalgia isn’t always a good thing.

Maya Kotomori: The title, Rarely Do I Dream. Rarely do you dream?

Trevor Powers: The title came to me during the last tour cycle. I’ve always meditated, but as I deepened my practice—starting with 20 minutes, then 40, eventually an hour—it began to feel like my soul was reaching beyond the curtain of home. The more I meditated, the more waking life felt like a dream. That idea shifted my concept of reality and made everything feel fluid. When I was on tour for Heaven Is a Junkyard, the phrase popped into my head, and I knew it was something I had to follow. In truth, reality is the opposite—I’m always dreaming.

Maya: Reality is so much perception, and perception is invention. I hear that in your production. I’ve been listening to you since I was 15, and when we got the email about this interview, my co-editor and I instantly remembered The Year of Hibernation. We were both so attached to that album in high school. There’s an artistic consistency from that album to Heaven Is a Junkyard to this one, the dreamscape synths. Do you approach sound technically, or is it more instinctual?

Trevor: I’m not a gearhead, but I’m obsessed with how sound carries emotion. Words have this visceral power, and I think sound works the same way. A song should feel like a living, breathing creature, like you can reach out and touch its skin. I build texture by running sounds through different processes, layering them until they match what I hear in my head. It’s all instinctual. I don’t know theory, so I work from feeling, trying not to overthink.

Maya: That makes sense. Memory is not real! I love telling people that. It’s just a constructed thing—when you recall something, you’re repopulating it in your mind. So creating an album feels like a natural extension of that idea, repopulating and reshaping the past into something new.

Trevor: Exactly. This project feels brand new to me, even though it’s existed for 15 years. I’m such a different person now. Meditation has given me clarity I never had before, and that changed everything. I used to force creativity, but now I realize that the best ideas surface naturally. It’s like a faucet I can’t turn off, I just have to keep up. When you prioritize being over doing, everything flows. The best form of creation comes from stillness.

Maya: That’s such a profound shift. Was there an inciting incident that led you there?

Trevor: Yeah. I went through health issues that forced me into stillness. I had to find ways to escape my body, and that changed my whole relationship with life. It deepened everything, my appreciation for people, music, even how food tastes. Without that, I don’t think I would have arrived at this way of seeing the world.

Maya: It’s beautiful when life forces you to rethink things. Speaking of memory, what was it like working with your family’s archive of home videos for Rarely Do I Dream? Was revisiting these more preserved memories a new process for you in writing music?

Trevor: It was a balance between building a new world and staying true to what was documented. Family camcorders only capture the beautiful moments—when things get real, the camera turns off. That contrast fascinated me. The lyrics could reflect one version of reality, while the home videos reflected another, with the truth somewhere in between. My music often plays with that tension. It might sound warm and nostalgic, but there’s always something darker underneath. That’s how I process things, by pulling my demons into an alternate reality and guiding them toward light.

Maya: That’s the spectrum of human emotion. The least effective sad songs just wallow, but the best ones acknowledge that every emotion is part of a larger journey. Even if a song sounds happy, there’s something complex under the surface.

Trevor: Exactly. Every emotion is valid, even the painful ones. Instead of running from discomfort, I’ve learned to sit with it, let it teach me something. If you ignore it, it’ll just find another way to reach you. I try not to label experiences as good or bad in the moment. Sometimes what feels terrible ends up being the best thing that ever happened.

Music has a mirror-like quality—it gives you what you need in that moment. I’ve written songs thinking they were about one thing, only to realize later they meant something completely different. The meaning shifts.

Maya: What’s a song that has had that kind of mirror effect on you?

Trevor: ‘Anthony’ by The Durutti Column. It’s on an album called Sex and Death, which is one of my favorites. That song always gives me exactly what I need, no matter my mood. It feels beamed in from another world.

“Every emotion is valid, even the painful ones. Instead of running from discomfort, I’ve learned to sit with it, let it teach me something.”

Maya: Album-specific question—who’s Lucy?

Trevor: Lucy started as a real person from my childhood, but over time, the name took on symbolic meaning. Now it represents different emotions and memories at different stages of my life.

Maya: So Lucy isn’t just a person…she’s an aura, a presence. Is she interchangeable with nostalgia?

Trevor: I’m actually very anti-nostalgia. Nostalgia can be a prison. I have a relative who’s completely stuck in the past, and every day, it keeps him from living. For me, history is only valuable if it teaches you something about the present. Rarely Do I Dream might seem nostalgic because of the home videos, but I was careful not to let it become just a golden-hued memory. Family history has addiction, loss, and struggles that were never caught on camera. My job was to weave the full picture, the warmth and the darkness, because truth is always in between.

Maya: That balance is clear in your music and visuals. Even the title ‘Speed Freak’— that has layered meanings, right? Someone on speed the drug but also someone who loves going fast?

Trevor: Yeah. I realized after writing ‘Speed Freak’ that it’s about trying to outrun death. When I was writing, phrases just came to me, like ‘stray dogs’ and ‘bullfrogs.’ Later, I researched those words and found they symbolize death in different cultures. I had no idea at the time, but my subconscious was leading me there. That’s what I love about songwriting, sometimes you don’t fully understand a song until it’s finished.

Maya: Isn’t it wild how your own music can teach you things? Like your subconscious telling you something.

Trevor: Yeah, and that’s why I keep making it. It’s a way to process, to reflect, to move forward. Every song is another step toward the light.

Listen to Rarely Do I Dream here.