For Document’s Fall/Winter 2024–25 issue, Kyle Carrero Lopez examines LGBTQ+ organizations across the globe who are imagining a new definition of home and togetherness

“Utopia” lounges atop a palanquin held up by four hulking men at the buzziest level of the buzzwords pyramid. Descriptions of environments which feel safest for queer and trans people often deploy this weighty term, whether to describe festivals,vacation hubs, nightlife locales, or any number of community-building events. The word indexes paradise, unbridled joy, and freedom in one’s body and expression, all of which frequently feel out of reach for sexual and gender minorities in public life. Utopianism as a concept, though, rests upon a foundation fraught with political contentions. Commune movements around the world during the 1960s, overwhelmingly white and middle-class, emphasized a need to get back to the land in order to recreate a bygone, harmonious, utopian nature-human relationship; however, this goal raises the query of back to whose land, exactly, and by what means? These historical movements have played an important role in conceptualizing queer collectivity, and in order to continue to establish stronger communal living projects for queer and trans people, answers to this question and others—both practical and philosophical—will necessitate multivalent, multidisciplinary approaches. Historically queer public spaces, like the easternmost sections of Jacob Riis Beach in Queens, can serve as case studies for what this work entails.

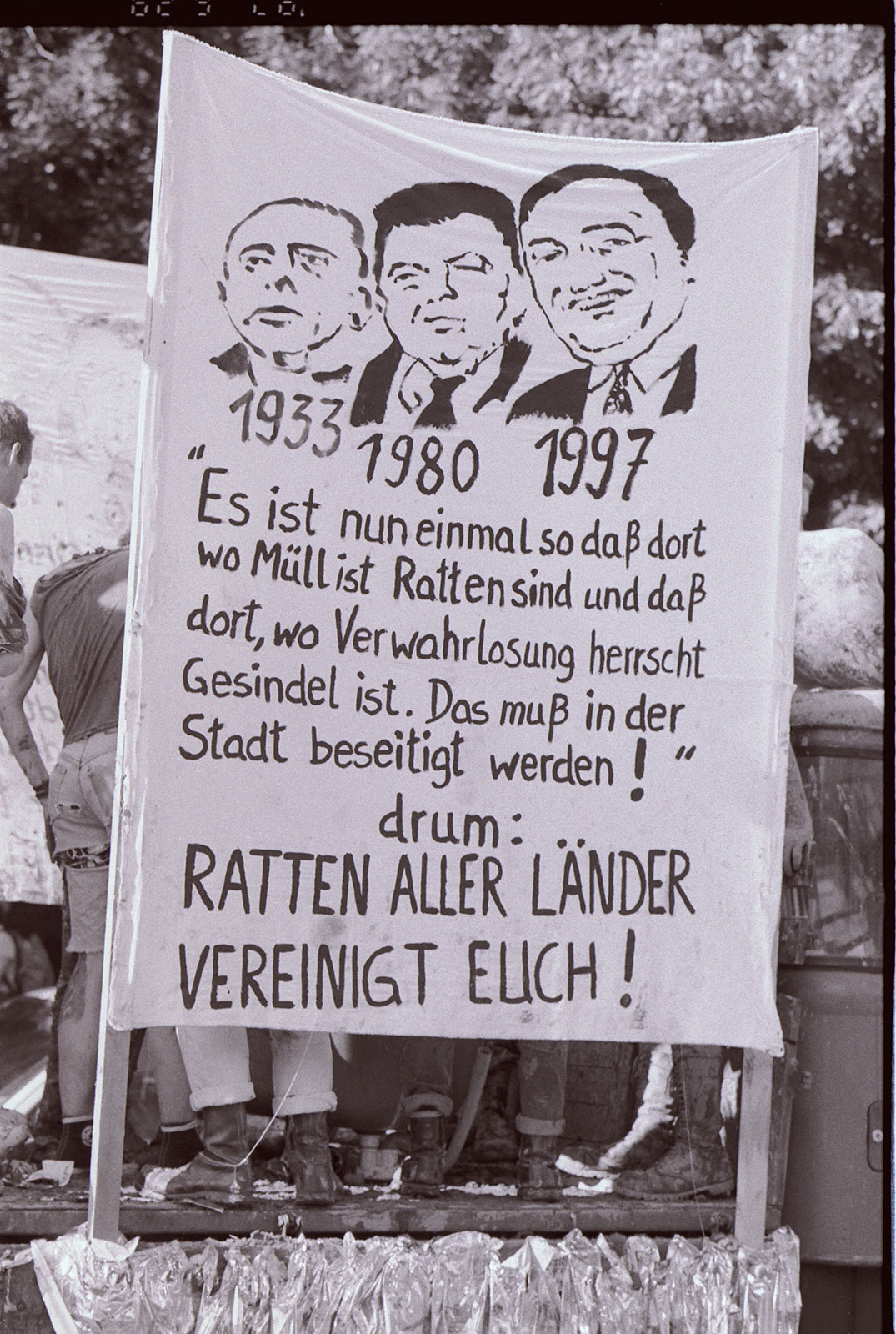

Riis Beach has been the site of a land dispute since the 2023 demolition of the abandoned Neponsit Hospital, which provided physical coverage for its queer sections; local activists have since begun raising money to form a community land trust where the hospital once stood, with the goal of building a health and wellness community center focused on the LGBTQ+ population. In “Four Notes on Riis Beach,” an essay published by the Pratt Center for Community Development, urban planner Addison Vawters questions how “queerness” and “indigeneity,” as political categories, come up against one another in conversations on claims to land and public space. Is it queer people, the City of New York—a government entity on occupied Lenni-Lenape land—or New York’s native population (meaning heritage, birth, or both), who should have the greatest say? Furthermore, how do we strive for equity for queer people when standard law tends to push for equality?

Brooklyn’s Stonewall House, opened in 2019, provides housing for low-income seniors while emphasizing its LGBTQ-friendly environment; however, as Leilah Stone notes in a piece for The Architect’s Newspaper, it would be technically illegal for the development to welcome an LGBTQ-only population. What other legislative limits are placed upon the idea of zones meant for queer people? For one: legal language customarily emphasizes protections based on family status, as in the Fair Housing Act, but this convention does not account for chosen family structures common for queer and trans people. The challenges and opportunities of material spaces like Riis Beach or Stonewall House demonstrate why legal and ethical considerations ought to play an even greater part in wishes and proposals for queer public space and housing than utopian theorizing does.

“Is utopia flat-out irredeemable, or can a concept rooted in the principle of better living for all remain salvageable despite its uglier applications?”

“Utopia”—literally meaning “no place,” from the Greek οὐ (“not”) and τόπος (“place”)—originates in Sir Thomas More’s Utopia (1516), a work of fiction based in the so-called “New World” which imagines an island republic whose systems have been conceived as the best for its citizens, or as close to perfect as can be. With this 16th-century creation (slavery included) as a guidepost, the idea of utopia erects a nexus between past and future through its double-ended framework, which at once reaches forward to the not-yet-here and backward for the once-was in an effort to improve upon the present. Gaia Rajan’s poem “Dent,” published by the Academy of American Poets, meditates lyrically on decay and survival as demands of the present tense: two qualities which pose counterpoints to utopian notions of beauty and leisure. In a note accompanying the poem, Rajan writes, “Utopia is a violent fiction: to imagine a past coherence confines us to a perpetual state of self-purification, corrosive not so much to our fallibility as our humanity.” By nature of its origin, standard evocations of utopia perennially hark back to a perfection based in colonial logics. Architecture inspired by the classic vision of utopian futurism also holds historic links to fascist ideology, as in mid-20th century Italy. For example, the village of Tresigallo was designed as a model city that could be replicated across the country, with beautiful, modernist, dreamlike structures that might have come to define Mussolini’s Italy had World War II gone differently. Is utopia flat-out irredeemable, or can a concept rooted in the principle of better living for all remain salvageable despite its uglier applications?

Queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz addresses this question at length in his landmark 2009 book Cruising Utopia. Muñoz suggests that queerness is not yet here, meaning that though of course queer people exist and always have, queerness is an ideality only reachable after significant cultural changes to our present: a temporal, spatial, and still out-of-the-way destination. This viewpoint necessitates forward-thinking approaches to the problems facing queer and trans people today with a simultaneous grounding in what has come before. His conception of utopia is not so dissimilar from the standard, double-ended utopian framework, the major difference being a sense of realism and pragmatism that the standard does not necessarily encourage in its affect of speculation and fantasy. The distant past and distant future share a certain likeness in that both reside within speculative, somewhat abstract realms. Much of what we believe we know of what life was like hundreds of thousands of years ago relies on (highly educated) conjecture; on a smaller, more personal scale, as critic and poet Vanessa Angélica Villareal explores in her personal essay collection on fantasy and popular culture Magical/Realism, the lasting impacts of colonialism, slavery, and other forms of informational interruption have made it so that many families’ understandings of their ancestors are at least partially imagined and bordering on fictive (to illustrate: just as enslavement and its forced renamings have left many lineages untraceable up to a certain point, Villareal writes on how some family members’ requisite name changes while fleeing from domestic violence have made it difficult for her to track their information). Like Villareal, Muñoz sees the role that fictions play in our everyday lives and advocates for more rigorous interrogation of their capacity to obscure us from greater understanding as to the extent of our knowledge. Queer theory is wonderful on its own, but its truest potency lies in how it can intersect with consequential enactments of law, architecture, and public space.

In the essay “Home Is the Place We All Share,” published in the Journal of Architectural Education, architect Olivier Vallerand analyzes a number of domestic installations that physicalize possibilities of “queer space,” meaning places whose designs contain qualities one could identify a queer sensibility in even without the presence of queer people in them. The Pumpwerk Neukölln studio-house in Berlin—commissioned by Scandinavian artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset and designed by German architects Nils Wenk and Jan Wiese—negotiates publicness and privacy in a way Vallerand notes as queer in its point-of-view, for example. It is a single building that combines two lofts for the artists, guest rooms, and shared living areas; the central gallery and workspace is accessible via the main entrance, while the second equivalent space located in the attic can only be reached by traversing through the rest of the building, including the private bedrooms. As Vallerand writes, “The unusual spatial organization of the building positions queer lives, long forbidden to be seen, as worthy of being visible to all.” Although Vallerand notes the constraints and flaws of this particular design for its occupants in practice—and acknowledges the white, male, and upper-class context of much of Elmgreen and Dragset’s commissions and projects—this and similar aesthetic experiments in more sociable living arrangements can offer useful information when considering how other buildings designed for queer and trans people have appeared and functioned.

There are, of course, fundamental differences in experimental housing by (and largely for) a clientele of wealthy gay men versus housing meant to address societal failures. In Argentina, the city of Neuquén’s Costa Limay Sustainable Complex for Transgender Women was inaugurated in 2020 as the country’s first housing complex dedicated to transsexuals, funded by the local provincial government. The complex was established by Mónica Astorga Cremona, a nun and longtime trans ally who received a letter from Pope Francis extending his blessings for the endeavor. Tenants pay no rent and can continue to live for free as long as they comply with typical rental regulations. The two-story building has six apartments on each level and features a multipurpose room, a park used as a vegetable garden, a recreation area, and a parking lot. Here, filling urgent needs of livability takes precedence over innovations in design.

“Queering dystopia could mean striving to make our current reality not only survivable, but also joyous for—and celebratory of—queer and trans people. In the same way queer and trans communities have managed to artfully reclaim corners, nooks, filth, holes-in-the-wall, and the nighttime, can there exist a political home in queer dystopia as a complement to the work and visions of queer utopia?”

Also in Argentina, the Hotel Gondolín in Buenos Aires exemplifies a queer, communal living project whose structure fosters radical possibilities beyond the baseline asks of housing. The Gondolín was originally a family-owned hotel near the red-light district. Starting in the late ’80s, the owner began subletting rooms to trans and travesti women of the area at higher rates since other hotels would not accommodate them. In 1999, these women banded together to occupy the building after its ordered closure and subsequent threats of eviction, reclaiming it as their own and working to improve its conditions. In Queer Spaces, edited by Adam Nathaniel Furman and Joshua Mardell, architect Facundo Ravuelta writes: “Inside, the residents refer to each other according to a sort of organizational chart with familial names, in which the oldest and most experienced acquire the affectionate titles of Aunt or Grandmother, roles that are assumed and carried out with pride. Thus, the Gondolín is a concrete exemplar in expanding the means of survival for the travesti community and others beyond the nuclear family, producing and spreading new social structures, capable of favoring a different and more suitable kinship system.”

Additionally, the Gondolín has provided educational resources for many of its residents in order to expand their access to opportunities beyond survival sex work. This emphasis on professional development is also a pillar of New York City’s G.L.I.T.S. One South, described as “a 12-unit apartment building in Queens that is not only dedicated to housing predominantly Black trans community members but is Black trans-owned.” Founded by the queer advocacy organization G.L.I.T.S. Inc. in 2020, residents of the complex are selected through the G.L.I.T.S. Leadership Academy, which hosts guest lectures, workshops, and other programming onsite. “The opening was the beginning of creating Black trans equity and designing the home of our future,” G.L.I.T.S. founder Ceyenne Doroshow told the local news site QNS. Doroshow’s words speak to the exact spirit of queer dreaming and dream-realizing that characterizes G.L.I.T.S. and shows what queer theory put into action—whether learned from study or embodied through experience—can look like at its highest level.

Muñoz’s perspective on queer utopia was shrewd, clear-eyed, and remains highly relevant because of how it refuses distant, abstract ideas of utopia. It favors a view grounded in contemporary life and in queer and trans peoples’ ability to collectively harness “educated hope” to energize the present with strategic, intentional building toward what comes next. He understood that truly queering utopia would mean more than simply adding queers to an established utopian blueprint, and that it would require subversive, paradigm-shifting tactics as well as reimagining language, ways of seeing, and ways of being. To that end, I wonder how a reframing of “dystopia” might usefully add to the many thoughts surrounding utopia’s upsides and downsides. Culture writer Jenika McCrayer has written about how fictional dystopian and post-apocalyptic scenarios often center on conditions of precarity and the fight for survival that people on the margins of real-world society already experience in their daily lives. This readily applies to queer and trans people (particularly Black trans women), who face housing insecurity, employment barriers, trans-affirming healthcare challenges, and public harassment, as well as mental health issues exacerbated by the factors just listed. All of these challenges in combination with big-picture crises of affordable housing, economy, climate, substance abuse, war, gender-based violence, limits to rights to bodily autonomy, malnutrition, and so on, and on and on make clear that dystopia is already here. To feel otherwise would suggest a level of shielding from horrors and imbalances of the world that is not afforded to most.

Approaching the dialectic of utopia and dystopia this way, queering dystopia could mean striving to make our current reality not only survivable, but also joyous for—and celebratory of—queer and trans people. In the same way queer and trans communities have managed to artfully reclaim corners, nooks, filth, holes-in-the-wall, and the nighttime, can there exist a political home in queer dystopia as a complement to the work and visions of queer utopia? If utopia merits repurposing, then so, too, might dystopia.

One queers dystopia, perhaps, by viewing the world with as pellucid a lens as Muñoz’s, by refusing to veer away or lose oneself to escapist tendencies for too long. Queering dystopia entails offering as much help as possible to neighbors within two miles as well as to those on separate lands, from Cuba to Sudan to Palestine and further. Queer dystopia means a dystopia with the most creative and unexpected solutions in place. This is the potency of queerness as a force of political activation: it spurns binaries, lets the world be at once large and small, and allows people to see that none of us is truly so distant from the other that we cannot still collaborate, that we cannot still shape and inhabit a practice of togetherness, and that we cannot still make tangible and miraculous things happen in whole new ways that disrupt this planet’s established hells.

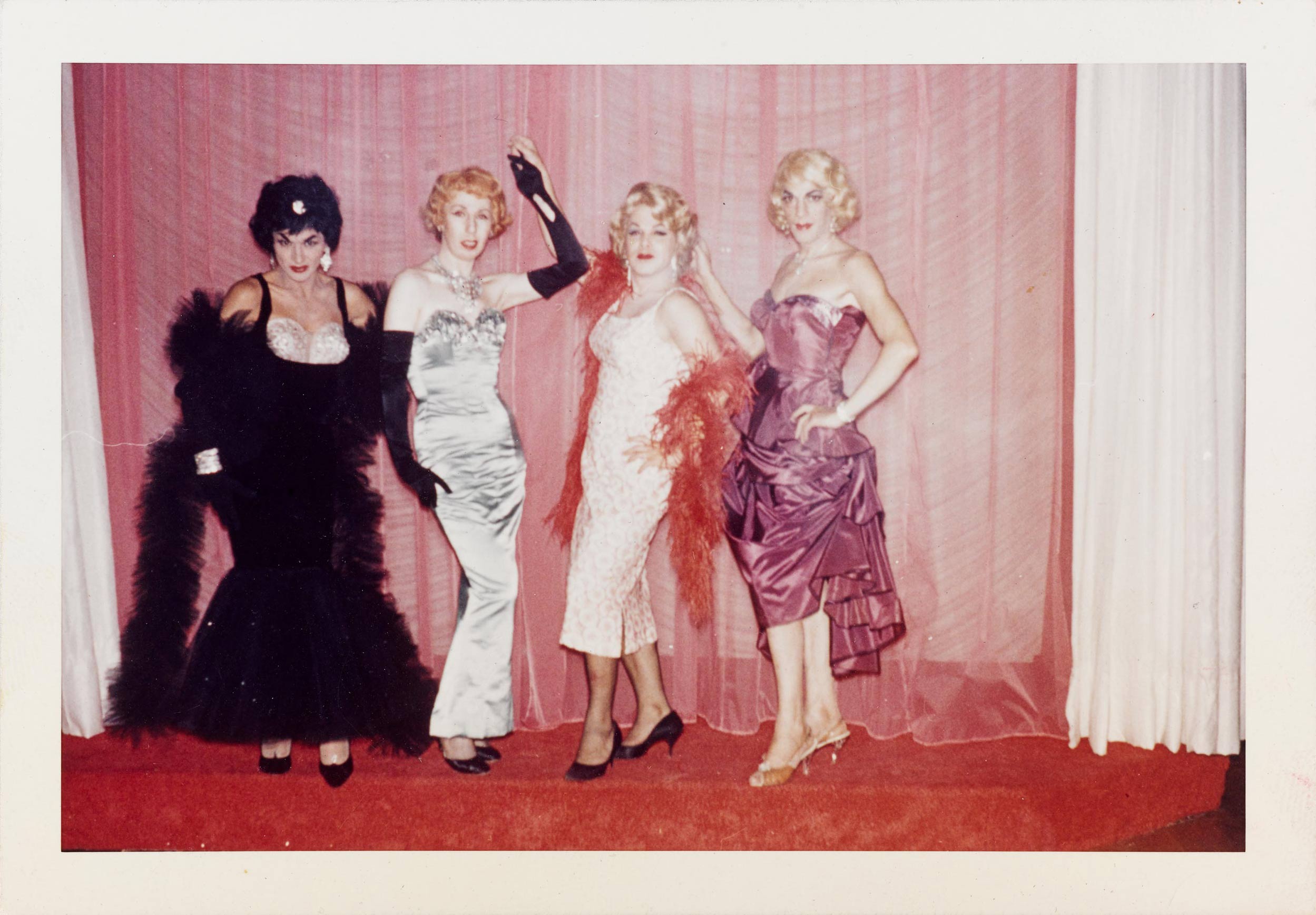

CASA SUSANNA

During the 1950s and ’60s, in New York’s Catskill Mountains, Casa Susanna served as a respite to people who then or later identified as either transgender women or cross-dressing men. At the time, these individuals’ identities and self-expression could be criminally prosecuted in much of the US. These images were shot by Andrea Susan—Casa Susanna’s official photographer—between 1964–69.

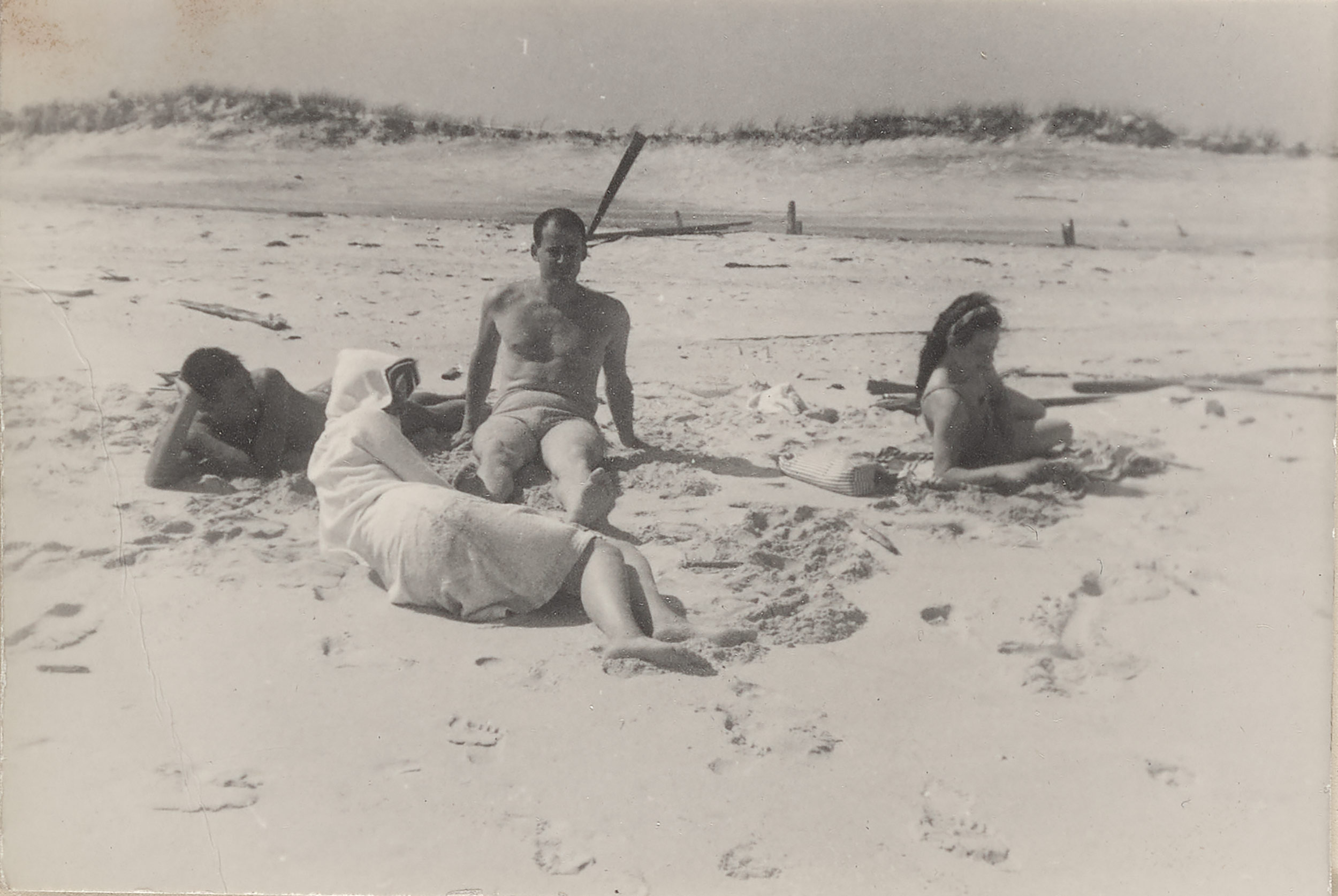

FIRE ISLAND

For around a century, Fire Island, off the coast of Long Island, has been a queer haven. These pictures by the artist collective PaJaMa (Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French) showcase a carefree conviviality that endures on Fire Island to this day.

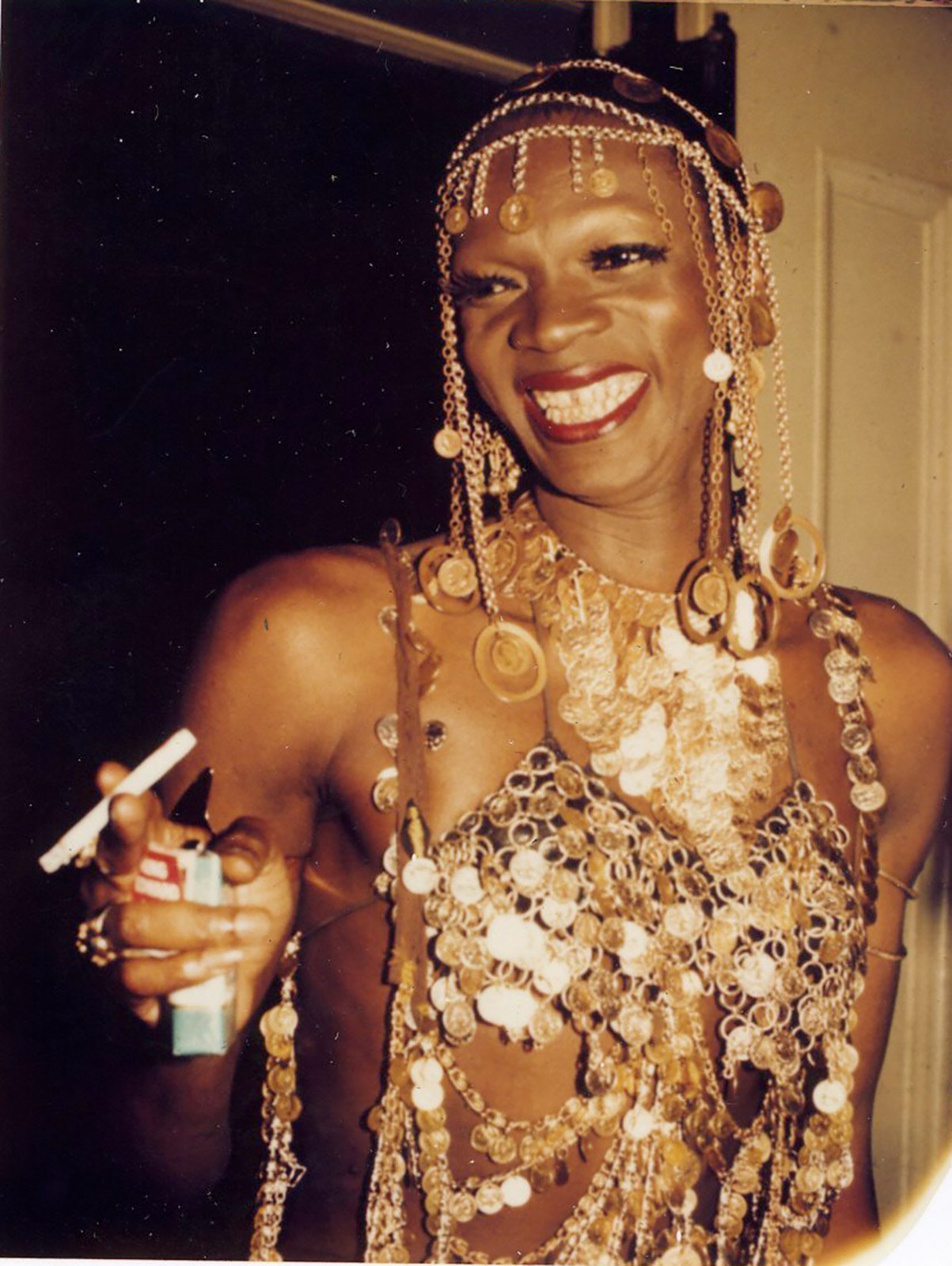

THE CASTRO, SAN FRANCISCO

In part attributed to the dischargement of gay US military members, starting in the 1940s the Bay Area became a queer refuge. In the ’60s, around the time of the Summer of Love, the gay community would begin to concentrate in the Castro neighborhood, making it one of the first such predominantly queer urban areas in the country.

WOMYN’S LAND MOVEMENT

Collectives, often ascribing to some variety of “lesbian separatism,” saw women engaging in rural, communal living practices. Many were photographed by Ruth Mountaingrove, who founded WomanSpirit magazine and lived on a gay commune in Oregon. Clockwise: Country Women’s Festival in California’s Mendocino Woodlands; a graduation celebration in Oregon; a sign from a solstice celebration at Jill and Ellie’s Women’s Center in Massachusetts.

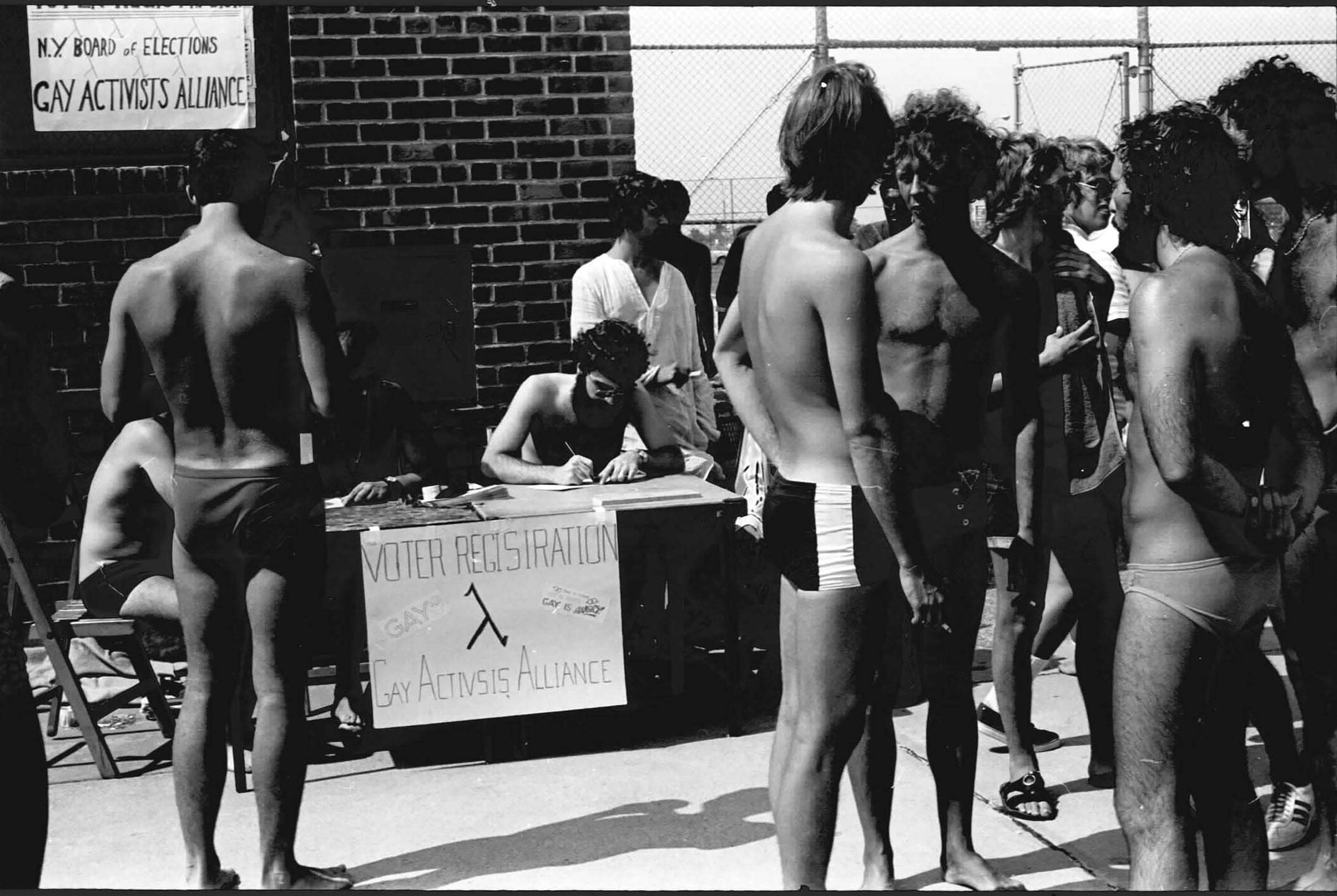

RIIS BEACH

The People’s Beach at Jacob Riis Park has long been a queer- centric oasis in New York City. These images depict the GAA softball team and a voter registration drive in the early ’70s.