Tracing sounds and symbols from across the Americas, the 55-minute performance channels the aesthetic flows within WangShui’s Arsenale installation

In the Artigliere gallery of the Arsenale for this year’s Venice Biennale, the New York–based artist WangShui staged an installation featuring three paintings on aluminum and the netted LED-video sculpture Lipid Muse (2024). Their Cathexis paintings use pigment from red beetles and trace the aesthetic flows between Asia, Latin America, and Europe, as well as between human and machine. The result is by turns moody and enchanting. In the paintings, WangShui unwinds the symbology of serpents as representations of knowledge, violence, healing, and love.

Earlier this year, WangShui connected with DJ and creative director of Mexican music label NAAFI Alberto Bustamante and curator Sam Ozer to conceive a performance as a “closing ritual” for the biennial exhibition. The resulting 55-minute performance, La Culebra, leaps from Indigenous Mexica iconography, rituals, and aesthetics, centering the deity of Coatlicue who is associated with the underworld and is frequently depicted with serpents. The singer La Bruja de Texcoco becomes a serpent herself, her voice synthesizing unknowable pre-Colombian musical traditions with Western classical music and electronic beats, composed in collaboration with Bustamante and musician Lauro Robles.

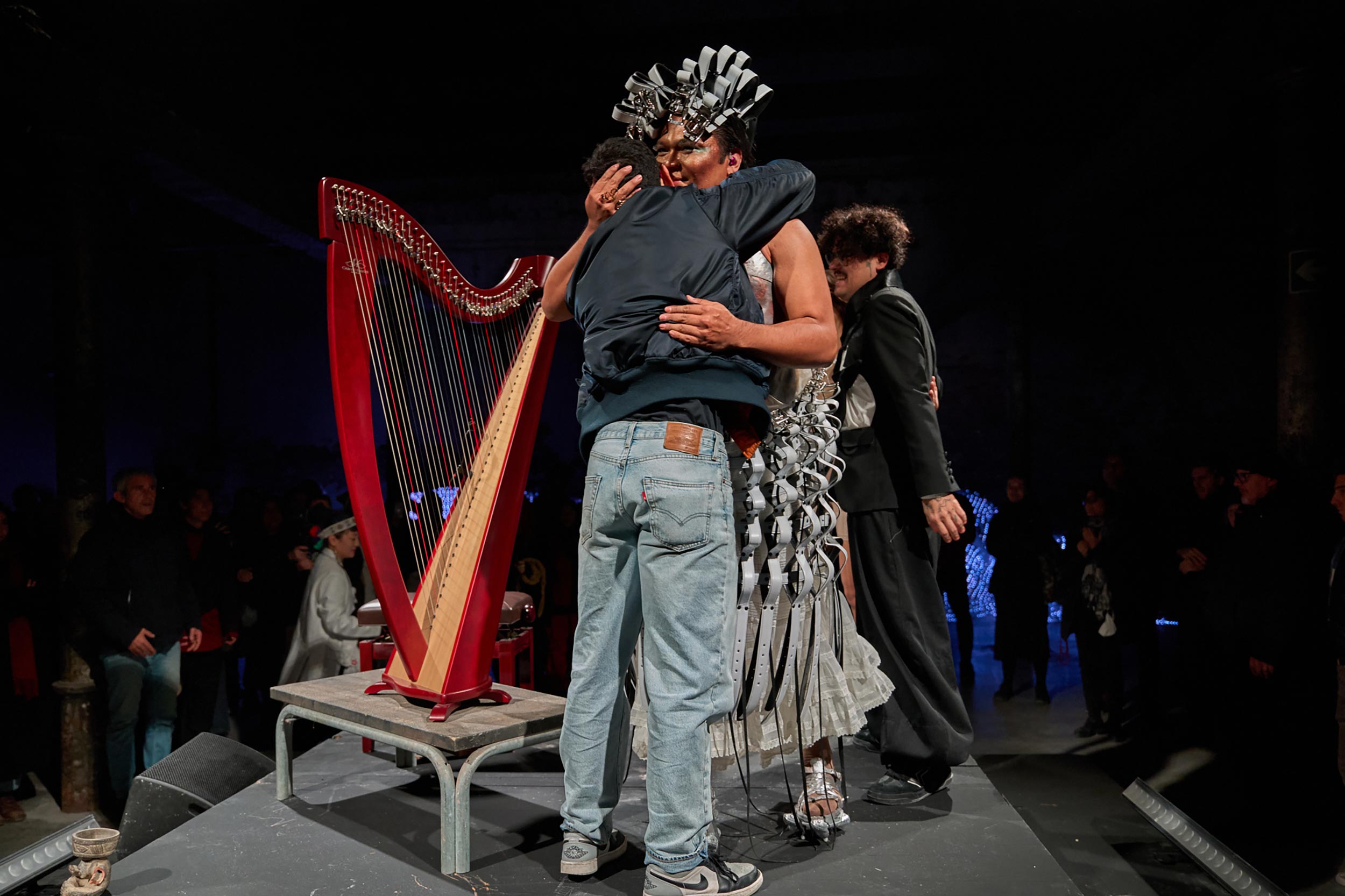

To open the performance, artist and healer Little Owl and artist and DJ Debit adapted the music they created for the Lipid Muse installation into a live ceremonial prelude. Everyone was dressed in costumes by Mexican artist and designer Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. At the afterparty, Bustamante, Robles, and Debit DJedd with masks and accessories from Kuboraum, who supported the project.

To reflect on this potent, multidimensional ritual of love, co-producer, curator, and founder of TONO Festival Sam Ozer joins WangShui, Bustamante, Robles, La Bruja de Texcoco, Sánchez-Kane, Beatriz, and Little Owl for an intimate exploration of La Culebra.

Sam Ozer: There are so many forms this project has taken and in every iteration it has grown with collaborators and references across geographies and artistic genres. First there was research between Alberto and Lauro about Mexican deities, with specific attention to Tlaloc, which led them to work with artist Pepx Romero and to create Atlacoya, a techno-opera we presented in Mexico City for TONO Festival 2023. Now that research has inspired La Culebra, a performance ritual for the 60th Biennale de Arte finissage. This recent premiere responded to Shui’s installation Lipid Muse [2024] and included a performance prelude by Delia and Little Owl who created the sound component of Shui’s installation. Can we speak about this process of transformation and regeneration across the work?

WangShui: My original project in Venice was all about love. How rigorously we must cultivate love within ourselves so that we can be better conduits and amplifiers of it. For so long, Alberto has been doing that with NAAFI. He created an expansive platform for all these underground sounds from Latin America and disseminated them all over the world. In that spirit, and in the spirit of the greater exhibition, it felt so important to join forces and offer my installation in the arsenale as another resonator for that mission.

Alberto Bustamante: In the early days of NAAFI, I remember something that Lauro said that really stuck with me, which is that when you gather people in a kind of ecstasy, like on a dance floor, and you communicate ideas when you’re having fun and not really intellectualizing, more people have their guard down and they’re more willing to incorporate new ideas.

Lauro Robles: It’s easier to influence people in a subliminal way through festivity.

Bárbara Sánchez-Kane: For me, this [project] is a rhizomatic love poem between friends and people you admire.

Delia Beatriz: I think what we’re trying to do is to break through all limitations and create a sensorial revelation. When we came together in the performance, it actually felt like we were working together all along.

Sam: Alberto, can you speak about your research for this piece?

Alberto: The earliest precedent to La Culebra is when Lauro and I were invited to perform at Cumbre Tajín, this Indigenous Mexican music festival, and we had the idea of revising the Mexica pantheon of deities. Then during the pandemic, we relocated the NAAFI studio to Azcapotzalco, a place that has this very heavy significance to the historical moment when the Tenochtitlan conquest happened. As we couldn’t organize parties, we were doing a lot of psychedelic hiking to different volcanoes around the basin of Texcoco or the Mexico City valley. In this region, this cosmovision of the Tiemperos is very present. During this time, Lauro told me he had taken a master class from the Institute of Aesthetic Research at UNAM, where the professor asked, how can we approach these subjects not from an archeological, historical perspective, but as living art? One thing she spoke about was the Tlaloc monolith which sits outside of the anthropology museum in Mexico City. There’s another precedent to our story, which is the documentary, The Absent Stone [2013], where we learn that the Monolith is not actually Tlaloc, or the male representation of the [Aztec] god of water and rain, but it’s actually Chalchiuhtlicue, which is the female form, or the duality of this same deity. So this idea that this stone was female at the beginning, and then the state decided to turn it into a male representation, was, in our thinking, an act of gender violence.

Lauro: We wanted to tell a story beyond that documentary, because that documentary was the articulation of political historical fact that through time makes [this narrative] real. The museum is this positive story that solidifies a narrative. It doesn’t matter if it’s real or not, but it leaves no space for imagination or evocation and poetry in reading the cultures through their art. The state created this whole operation which not only included moving the stone from Coatlichán to the city, but also a set of propaganda which included parading the stone around Zócalo in Mexico City.

Alberto: You have to think about the Coatlichán people who were contesting the government’s desire to take away their stone because it was an active site of worship. We really dived into the literature, the tiemperos and graniceros or the good and bad brujos who relate to Tlaloc and control the weather, and we started conceptualizing a performance. The idea was that the stone one night wakes up in the middle of the sidewalk, and it’s like, ‘Where am I? Who am I? Why am I here?’. And they then perform a psychedelic peyote ceremony, where they start a de-identification quest. And during that trip, the stone visits the different deities of the Mexica pantheon. They first go to the king poet Nezahualcoyotl, who was the last monarch or tlatoani of the Texcoco city-estate. And he had a very ecological or sustainable sensitivity.

Lauro: He had developed political, religious, and military thinking, which is called flor y canto, flower and chant, which is the eco-existentialist relationship between the self, the soil, and the reminiscence in the earth.

Alberto: Xochipilli is another one of the characters. He was called the prince of flowers and is this stone monolith that also comes from the same region as Tlaloc/Chalchiuhtlicue. He has psychedelic plants or medicines that are endemic to this region of the world engraved on his body. He has tattoos of peyote, ayahuasca, marijuana, daruta, or floripondio and tobacco leaves. He is considered the patron of the arts—dance, singing, and music. What’s funny is when we thought about the character of Coatlicue or the dame of the underworld who was associated with snakes, we conceptualized it thinking about Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. We wanted her to be a fashion designer and the underworld to be a showroom. In a way, it’s a mere coincidence that Shui’s installation and paintings feature all of these serpent motifs. For Venice, rather than Bruja again personifying the duality of Chalchiuhtlicue/Tlaloc we thought she could now personify Coatlicue and also respond to the serpents in Shui’s paintings. There are all of these synergies that have shaped the work to be what it is. And this is where it gets sort of like magic, that the coincidence aligned with the themes that we were thinking.

Lauro: And then we also considered this speech, that Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor gave by the side of Hernán Cortés accepting the Spanish conquest, which is the Consigna de Anáhuac. He basically says we’re not going to believe in our gods or traditions anymore, but in 500 years we’re going to come back. And that has to do with Mexicanity in the 20th century and how the night of the 500 years is taught. There is so much significance, because that speech was given in what is now the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, which is also where the state repressed the students in the ’68 protests.

Alberto: The performance has all of these historical ties and references that the audience doesn’t really need to know, but they are embedded in the piece.

Sam: Beyond historical research, the piece also incorporates a wide range of musical references—including pre-Columbian practices, European baroque instruments, and contemporary electronic sound production. Can you speak more about this layering process?

La Bruja de Texcoco: In music, there are people who read music scores, and I come from that school. I began to realize that in Mexican music you don’t read, everything is by ear, everything is by memory, everything has a historical connection, and that Mexican music is not learned in school, but by traveling and meeting traditional Mexican musicians. I am not a traditional musician, I am an interpreter of Mexican music who started out as an academy musician. Traditional Mexican music is a reflection of the baroque music that was in fashion in the 1600s and of European instruments that were brought to Mexico. A Mexican jarana jarocha is a version of a Spanish baroque guitar and a Mexican arpa jarocha is like a camac harp that I played here in Venice. There are aerophones, membranophones, all kinds of instruments that come from nature that exist from pre-Columbian times that I use—but there is no record of how to play them. In reality, there is no record of what pre-Columbian music was like. But that’s the nice thing: that I can give it as much openness as I want. That’s where all my processes come from to make an interpretation of how it could have sounded. The music comes from the imaginary that the three of us have of coinciding on how we can reinterpret our identity as Mexicans from our experiences. That is what makes it super cute, because it is something that we use from the past, not only the past in the Americas, but also from the knowledge of music here [in Europe], and taking it to the future. I do feel like a Mexican futurist. However, the research is not limited to Mexico. I also use Latin American instruments from Peru, Guatemala, and Colombia. I’m removing my label of being someone who only makes Mexican music and integrating everything I want.

Lauro: The Mexicanity or the concept of being from there solely or the idea of what happened before the Spanish came dissipates when you think about what Bruja said about baroque music, of how instruments were coming in from Europe, and how the tuning is super important for how the traditional music passes through generations. I think reimagining academic or classical pieces is also disruptive and reconsiders the meaning of those songs.

Delia: In my research, I’ve actually focused on the tuning of Maya wind instruments. In the mere association between two notes, even those relationships need to be questioned. As Lao and Bruja were saying, everything we’re doing is interpreting, so everything is fictional in a certain sense, because we’ve never had recordings of how any of the music sounded. And I was particularly interested in the relationship between pitches being a whole system of thought that we only have access to some of. All of this legacy that we can only approach through fragments.

Sam: Delia and Little Owl, how did your research inform the La Culebra performance prelude and for the sound installation?

Delia: My process was guided by conversations with Shui and has three main elements: Little Owl’s voice and interpretations; ocean sounds, which were a combination of Little Owl’s ocean drum which I then synthesized with some drums; and Shui’s breathing and snoring. We recorded Shui’s breathing in an anechoic chamber, which is a studio that’s designed to have no resonance and no echo. This music which was composed for the installation became part of what we performed for the prelude. For the performance, we specifically highlighted the ocean drum.

Alberto: This is where a lot of elements overlap between the music that we developed together with Bruja and Lauro and the music you guys did together, such as exploring historical reimagining and sci-fi. They both have ritual and ceremonial aspects where you not only play music but also channel energy. Delia, you were saying last night as a joke that Shui gathers all of their witches…

Delia: Yeah, but it’s actually true [laughs and nods]. I think that there is a metaphysical thing which is inherent to all music because it’s a process of managing frequencies. Your body has to become something else in the process of playing music.

La Bruja de Texcoco: For me it is very important to keep myself centered before leaving a show as my body is always in action. In embodying these characters, even La Bruja, it is a process of generating me and literally putting my flesh in this. It is not easy at all, because it is not only putting my body in, it is putting my energy and transitioning to something else. It really gives me a power that I don’t have in the street.

WangShui: To me, this piece was not a performance. It was an expansive energy exchange that will shift frequencies and reverberate in the world. La Bruja, Lauro, Delia, and Little Owl are each such humble conduits. I see them each as powerful prisms that bridge different dimensions of time, history, and trauma. They are some of the most powerful healers I have ever encountered. I am so humbled by all of their work so it was a great honor to bring them together in Venice.

Alberto: Little Owl, could we maybe expand on the different ceremonies and rituals that are part of your practice and how they are part of the music?

Little Owl: The first time I saw Shui’s work it was at the Guggenheim Museum and I didn’t even know the name of the artwork, but immediately it hit me as a cosmic serpent. Cosmic serpent is a concept and actually, a book written by an anthropologist about shamans who were able to access, without any modern science, the existence of the DNA of all beings and the source of the universe. So the cosmic serpent was basically a multi-dimensional state of the origin of the universe. And when I saw Shui’s work I told them about this and they shared that that’s exactly what was in their mind. Shui then invited me to make the musical piece to go with the installation. They wanted me to open a portal of multi-dimensional energetic space, so that we could bring people into that meditative state, to experience their artwork. I was using a lot of shamanic instruments, like chakapa rattles, and some other rattles that are very earthy—it touches every part of your soul and opens up your consciousness, in a way. The chant is the shamanic mantra that is channeled from the spirit of the jungle, the plant spirits. These shamanic songs carry a very specific vibrational frequency.

Delia: It was epic being in front of you and recording with you. I didn’t have to add any foley or sound effects. Everything was already encoded in the chant because of how you receive it through these historical or ancient traditions. I didn’t have to put, like, the sounds of frogs. I already felt all the earth, all the little cosmic elements, just with sound, just with the song itself. With my sound design, I usually had to make it really explicit; whereas here, just having a whole track of Shui breathing was enough. The sound of the serpent without effects.

Alberto: Can we maybe dwell on this idea of how it is a gesture? Shui calls it frequencies of love or a gesture of love or generosity.

There are people who are in tune with this ancestral knowledge either because of their heritage or where they come from. There are others who have ritualistic access to this type of information from performing in ceremonies or taking sacred medicines; however, there are so many people that have zero access to this ritual time and spaces or practices. Specifically, more Western people, in this European context where the Biennale is happening, can’t really find those magical spaces or these ritual spaces, but in a way, this performance and this piece and your music and the whole sum of these efforts, give for a brief instant access to this type of sensibility or to this source. Can we dwell on this, like, magical dimension of the work?

Delia: I think that’s the benefit of working in the context of art versus or music. It has a lot to do with the reception of an audience. Sometimes shock can be an effective way to engage. However, I think approaching this piece from love feels unique.

Alberto: I’m also curious about how many people get super protective about these practices and are like, ‘No, they’re not for everyone.’ Gatekeeping spiritual practices. What do you think?

Little Owl: The world is really shifting. You can see how many people were in the audience last night. People are gravitating toward the vibration. It doesn’t matter what we do, as long as we’re at a higher vibrational frequency that people can resonate with. The ritual itself can be any form or shape. It’s that interconnectedness that opens up people’s hearts and connects us. I find that a lot of young people nowadays are really more open. They’re more fluid. They’re more in tune with all that this is, with the interconnectedness of all things. And a lot of young people came to us after the show. I really believe that the world is ready to reconnect to our ancestral wisdom. Because in the tribal culture, people live with earth, not on earth. It’s part of us. No living being has any separation from us all. I think that Mother Earth is calling that to come back to us.

Delia: I really do think it’s a matter of format, like you’re saying. We could have easily been reading a sermon about all these ideas in words, but the way it’s received when it’s liquefied in the cosmic frequency of music changes the reception. I do think it’s just somehow more receptive. It’s almost like hacking through stuff that would have been blocked off, either by gatekeepers or the audience themselves who might be afraid to receive something spiritual.

Little Owl: And the funny thing is, most people probably don’t even know what we’re chanting or the language we’re singing. I was singing in Quechua. And people don’t even know what kind of ritual we’re performing. I think people are just fascinated and I think that is the sincerity that we have when we create a ceremonial state and call the spirits of all seven directions. It connects us to something vast and universal. Music really is the language of the universe — something everybody can resonate with. It doesn’t matter what we are doing as long as we’re in that vibrational frequency that carries unconditional love.

Love is the medicine, it is the fabric of the universe.

WangShui: I really wanted to bring together the brightest sounds of love that I have encountered in recent years and see what happens if we interpolate them. To me this exhibition enacted a major global axis shift so it felt good to give it a final push. Each of you had such a different frequency of love that you were beaming! Everyone in the room felt it so deeply and will carry that with them into the future…what a gift!