In his debut solo show ‘No Regrets Because You’re My Sunshine,’ depictions of a social network reveal the creative self

The painter Lorenzo Amos lives modestly in a one-bedroom apartment in a building in the East Village. For four years, his living room had become his studio, strewn with canvas stretchers and brushes marinating in cloudy water. He woke up every day and began. Now with a new studio in Brooklyn, Amos no longer has to paint from home. Still, traces of artistic activity that took place in the brick-walled apartment remain haptic and alive on his paintings’ surfaces. The apartment figures prominently in the works: Most of Amos’ portraits derive from episodes of friends visiting and posing for him in the living room, where the walls he drafted on act as both the physical backdrop and the mental map of the painted subject’s psychology. Perhaps the storied building itself is an endless archive of self reflection.

For his first solo show, No Regrets Because You’re My Sunshine at Gratin in Alphabet City, Amos resurrects the notion that depictions of others and the world can reflexively become self-portraits of their creator. Aesthetic production is subjectivity production. Amos’s process is recursively visible on the surfaces he depicts. In the exhibition’s eponymous painting, we see his apartment wall covered with paint—both accidental accumulation of residue from the artist’s brushes as well as intentional marks In the middle, he’s scribbled a depiction of his apartment building. Another instance revealing the artistic process itself can be found in Bedroom Dresser (A), 2024, which sees the artist reanimating trembling slabs of paint and spritz of wobbly streaks he has accumulated on the surface of his bedroom dresser. Here we see his humor, and his contemplative attention to fleeing and fleeting moments.

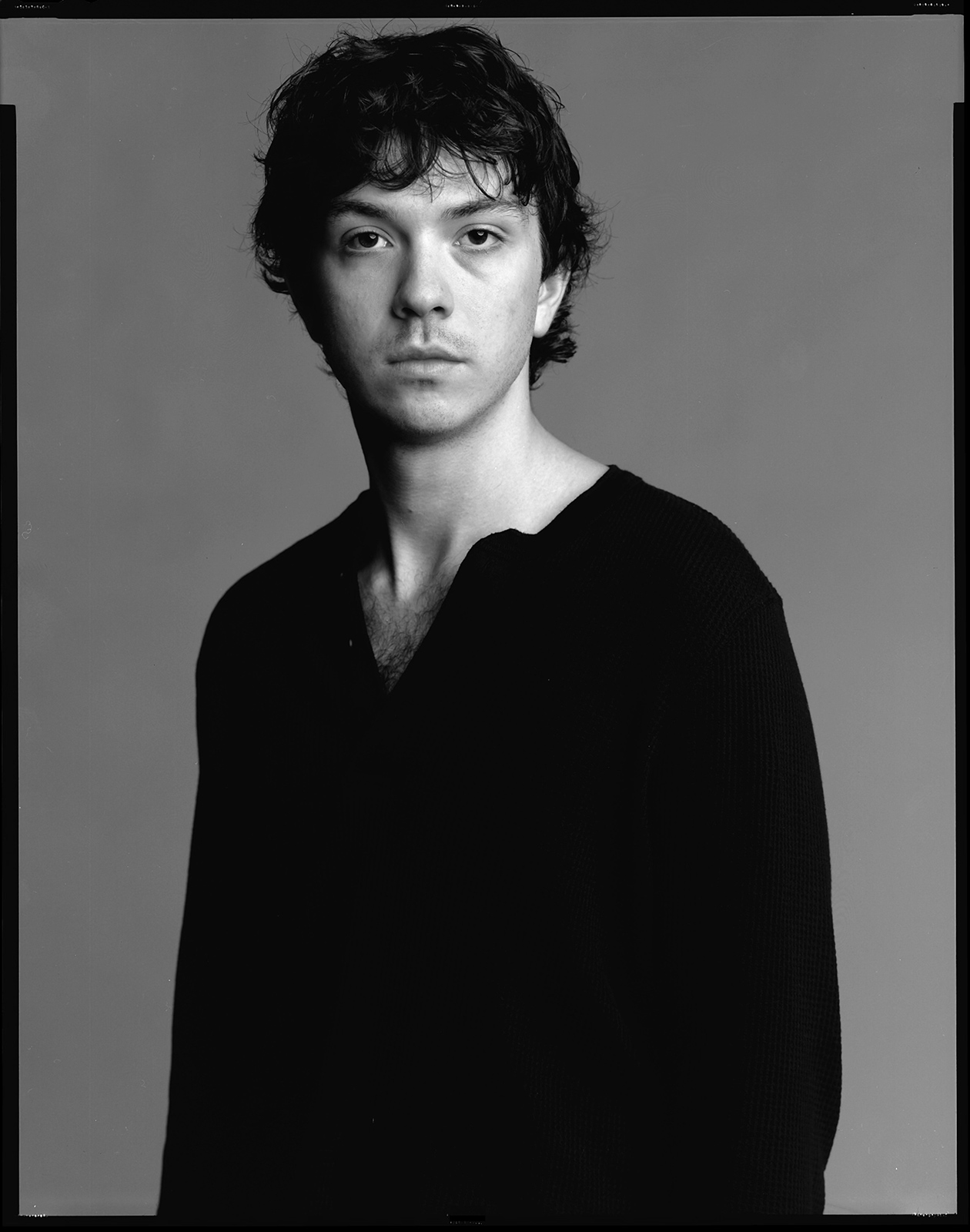

Amos’s images are deeply enmeshed in his social world. He frequently paints friends, turning the series of works into a representation of a network. Rather than feeling closed off, his penchant for rendering the porous boundary between a subject and their world imbues each image with a plenitude of perspectives.

Many of his works have resonant, even epic, origin stories. The Lovers (blue period) (2024)—whose title references Pablo Picasso’s Blue Period—was inspired by Hermaphroditus, a remarkably beautiful boy of Greek myth and nymph Salmacis’s object of desire; the boy and nymph eventually merged in a single form, a wish granted by a god in answer to Salmacis’s prayer. The Lovers (blue period) is far less melancholic than its title suggests. The free-flowing contours of its two figures (which previously existed on one of the apartment walls first as a preparatory work) are closer to the unrestrained lines on the ceramics Picasso made later in his life. Amos avoids the artificial grandeur of history painting and puts the shape of Hermaphroditus on equal footing with the constellation of indexical marks on the wall from which the first version of the two lovers was birthed. The lovers appear to have lost their bodily substance, with the contours of their merged body submerged into the environment of mark-making that is the painting itself. The considered surface which knows no dimension loosely holds their existence on the canvas, almost a symbol of no specific time and place, evincing the infinitely iterative and expansive prowess of the intimate stories the artist tells himself. In Amos’ portraits, the material world of embodiment and the immaterial world of psychic investment leak into each other and assume each other’s position.

Qingyuan Deng: Hi, Lorenzo. Should we start with the process of how you translate the graffiti-esque images that have covered your living space into paintings for the Gratin show?

Lorenzo Amos: I painted in my apartment because I didn’t have a studio. I was doing very thick oil paintings, much thicker than what I am doing now. And I was cleaning my brushes on the wall, just because I didn’t have much space for palettes. At the same time, I was looking at Lucien Freud paintings. In the background of the Freud paintings, you would see that he would also clean brushes on the wall. After a while I did the first wall painting—there was less paint on the wall than there is now—and it was an abstract painting of the marks that were already on the wall. Then I started adding much more intentional marks. I started doing the drawings on the white wall. I painted on it for three years, pretty much. It’s completely covered. Now what I’m doing is Matisse-esque—all the people running in a circle, right? The accidental kind of marks are accumulated over years, but these figures are done in a day. They’ve given me a completely new sense of freedom, as opposed to only doing portraiture, which is where my work started from. I was doing portraits of people, and then I started doing portraits of paint. I was painting the paint itself and wondering why abstract expressionism was boring to me. I was looking at Monet and Cezanne and all these different artists I almost wanted to copy in my own way. I found a way to create my own visual language through referencing these artists.

Qingyuan: What is the correspondence between reality and painting for you? While your paintings are realist to some degrees, they at the same time resist the easy categorization of realism.

Lorenzo: I think it’s just about painting whatever is real. I wouldn’t just do a painting of figures. First, they have to exist on the wall for them to eventually exist on the canvas. I adhere to what’s in reality. At the same time, I want to copy reality with faster images, more free, gestural, fluid kinds of images. I’m constantly pushing my representation of reality farther or as far as I can.

The reason my paintings are so attractive is because I make them look dirty but they aren’t. I like recreating the filth that’s in the studio or on my apartment walls, like the accidental messiness, and making it purposeful while still seeming accidental. You know Gordon Matta-Clark, right? He cuts out pieces of buildings and they become an artwork. Like, that’s what I’m doing. I’m just cutting out a piece of reality, a very flat piece of reality.

Qingyuan: Indeed they are flatter than reality. I also sense that your approach toward realism is not strictly autobiographical; rather you take the personal as a point of departure. They have a few degrees of separation from their subject matter which is your domestic reality or personal life.

Lorenzo: Exactly. Often, I take quick iPhone snapshots of my domestic spaces or people in my life and then transfer the images into paintings. Photography flattens the intimate details. It standardizes it. And I like my images to be flat. When I shoot models, I tell them, Don’t pass this line, don’t put your legs past this line, because I want the whole image to be compressed. These paintings are portals that viewers can almost just put a foot into, because there’s not so much perspective, and they’re not so deep. It’s only giving you that two, three feet of reality, not anything more. But that’s why it feels like you’re in the space with them. Basically, I am trying to tell stories of my life that may or may not exist, a romantic version of these stories. I want to revive feelings that were not here so much anymore because life has become a lot more plastic.

“Writing is very important to me. I’m trying to write a long storybook with pictures.”

Qingyuan: Yes, somehow that gets closer to the emotional truth. One of painting’s eternal motifs is the intimacy of painting one’s private drama happening in the studio or the home. That rings true for you. Do you see yourself as part of an aesthetic genealogy?

Lorenzo: Vincent van Gogh is a huge inspiration. I had been dedicating myself to painting my immediate environment in my tiny rent-controlled one-bedroom apartment for the past four years; and van Gogh lived in poverty out of principle, because he refused to paint anything outside of his working or living conditions.

Martin Wong once said he does not paint anything that is not within three blocks from his apartment. I am doing what he did, inhabiting spaces and making them part of my visual language too. My visual language is wooden chairs, shitty Persian carpets, paint, and bricks. I repeat them because I want my audience to remember them and form associations with them. I just want to have these motifs that people remember. When they see a painting that I paint, I want them to have the feeling of evoking a memory.

Qingyuan: I see an analogy between your painting and the tendency for modernist literature to collapse space and time to construct portals into memories. Writing about memory—Proust’s, for example—is a very back-and-forth activity that obsesses over its own internal flow and structure. Arguably there is a similar obsession, this gesture of accumulating mark-making itself as a sign of the artist’s passion, in your paintings too.

Lorenzo: I like the analogy. Writing is very important to me. I mean, all my paintings are writings. I’m trying to write a long storybook with pictures. I work obsessively on the surface of my paintings. I can repaint my walls over and over again—I have unlimited possibilities. So the repetition aspect of my paintings is also very important to me. And I agree with you, I don’t want to hide my passions. I want everybody to see it when they walk into my house. The mark is sort of the testament to me existing, right?

Qingyuan: There is one painting I keep thinking about, which is Bricks 1, 2024. It is a reversal of that Arte Povera gesture of taking bricks off the wall and recontextualizing them as units of expansive installations: You are returning or zooming into physical bricks and faithfully representing them on the canvas. It is condensed to the utmost and purely concerned with its own materiality.

Lorenzo: I saw Martin Wong’s bricks, and I was like, I could probably paint some better bricks than he painted. I love Martin Wong. He’s my favorite artist, but this is what I do with a lot of artists. I see what they did, and I think, Oh, I could redo this. Not in an arrogant way. I’m very confident with how I handle paint. Maybe I don’t mean better, but just more realistic. A lot of people have said to me, Damn, I thought those were real bricks. I was also looking at the color palette of Titian, Rubens, and Goya. They painted architecture so beautifully. I really love the subdued, muddy, and dim quality.

Qingyuan: Obviously the environment of gritty downtown is formative to your painting—the grittiness lends itself to a guerilla sensibility in your color palette and mark-making. Your paintings refuse to be fancy or concealed. However, I am equally interested in how the Old Masters have guided your painterly style. I know you spent some years in Milan.

Lorenzo: I saw a lot of Caravaggio paintings in Milan. The way he painted swords and daggers really excites me. I even got them tattooed on me. I also saw many Giotto frescoes all over churches in Northern Italy. Giotto used this ancient pigment called lapis lazuli, and I started using it too. I grew up in a very Catholic family, and I am used to going to churches and seeing Catholic art. Another time I went to the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and saw a lot of Piero della Francesca works. I fell in love with how he used sage green. I decided to use it in my paintings too.

Qingyuan: I suppose what makes your paintings contemporaneous despite being rooted in art historical traditions is how you paint your social network.

Lorenzo: I really could have done a show just painting celebrities, but that doesn’t interest me. My portraits are for and about specific people who are reflections of myself or what I want to be like. Most of them are just models to musicians to tattoo artists. For example, Leo of Leo Laying on the carpet [2024] is a pharmacist in Italy. He lives in the middle of nowhere, literally in a town with 50 people. I went to his town this summer. We went hiking. And it was very beautiful and great energy. Leo’s also tattooing, painting, and playing music on the weekends, and he’ll go to Milan and Rome or come to New York. He travels around a lot and has amazing tattoos. I painted a portrait of him because he is the funniest, sweetest, coolest guy. I should also say that I like using the same models a few times, because I like the idea of being familiar with my characters and repeating the same character in different paintings. Some of them are more abstract than others. I’m thinking about Alice Neel—the simple portraits can’t exist without the complicated ones.

Qingyuan: I am so curious about 4 landscapes, 2024, which is a painting containing four small landscape paintings. They definitely suggest a new direction in your painting. Would you ever want to do larger landscape paintings?

Lorenzo: One thing van Gogh did was that he would look at the landscape from his windows and paint the church and other buildings outside according to the framing of his windows. What van Gogh did interests me too because in a way that landscape is still part of the domestic but also extends the domestic into the other world outside. When I am ready, I’d like to do more window paintings.

Qingyuan: Have you seen Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art? Traces of the religious paintings in the show—how they deploy and repeat coded visual patterns to form a system of symbolic language—can be felt in your works too. Not to mention the flatness of reducing and collapsing figures into the composition too.

Lorenzo: I have not, I need to see it. I love medieval imagery. I also love carpets and tattoos. They are patterns that need to be precise and free at the same time. Very similar to medieval imagery. I feel like fresco paintings could be seen as tattooing the walls.