On view at James Fuentes gallery, the painter’s solo show addresses the many nuances of historical and cultural identity through figurative painting

Oscar yi Hou reconfigures the recognizable. The Brooklyn-based painter, who was born in England to Chinese immigrants, bedecks his portraits with a system of symbols as ostensibly oriental as souvenirs from a Chinatown gift shop. A flock of cranes flutter about. Yin-yang coils burst into balls of flame trailing claw-like tendrils of red smoke. Alongside subjects who sit or stand perfectly still, a double-edged sword burns fitfully; a pentagram sprouts razor-sharp wings; a stream of calligraphy wilts. On view until November 16, his tremendous show at James Fuentes gallery, The beat of life, sees those folds between homage and caricature pucker constantly.

Birds of a Feather aka: Chinatown Gangsters (2024) shows him next to close artist friends Amanda Ba and Sasha Gordon. They together represent a new guard of Asian painters who are charting alternative paths to complicating identity-based figuration. Their group portrait structurally resembles a folding screen, with actual brass hinges connecting its three panels. In the gangster garb of black suit and unbuttoned white shirt, they channel the Ghost Shadows, or the Flying Dragons, or any number of the other crime rings that ran Manhattan’s Chinatown half a century ago. Each artist seizes a third of the triptych. Like stone lions, they look at us with eyes that say, this is their turf—not ours. We don’t know what sort of foul play lies behind, or whether their stiltedness comes from agonies of guilt, or grief, or fear. These are oppressed people who become oppressors themselves. That metamorphosis is what makes the highbinder so tortured.

Coolieisms, aka: The Geary Act’s Rough Trade (2023) derives its composition from Martin Wong’s octagonal Sacred Shroud of Pepe Turcel (1990). In the latter, a Black man stands behind iron bars, his brawn barely contained beneath a white undershirt. Yi Hou cranks up that sizzle of sex. His painting features an Asian man and, more so, his rippling muscles. They swell like a pot of boiling broth. A tattooed Chinese dragon writhes across his shoulder blades. His back is turned, but he cocks his head slightly toward us, at once solicitous and menacing. As the title implies, he got thrown in jail for breaching a judicial farce of 1892, which insists he never leaves the house without his certificate of residence. So he has always been a kind of prisoner.

Then he travels some 90 years into the future. In Coolieisms, aka: Born in the USA (Go and Kill the Yellow Man) (2023–24), the American flag faces him the way it did Bruce Springteen on the cover of his 1984 album. But if the Boss is its hero, the yellow man is its enemy. Scrawled across the stripes are grimly sardonic lyrics from the title track. American troops shall gut the gooks. Our guy stands in a counterpoise, absorbed, concurrently a pumped-up prey and just another man on the prowl. He wants to be penetrated, if the star-spangled blue handkerchief on the right side of his leather assless chaps is a reliable indicator. A Manchu-style braid hangs, like a whip, down his back. Lust howls here, carnal and bloody.

The character wears a small gold hoop in his left ear—just like yi Hou. For the Coolieisms series, the artist lends his face to the thousands of Chinese whose exploitation built the transcontinental railroad during the California gold rush. But not his personhood. When severed from its owner, his likeness becomes an avatar, a repository for collective history. It’s quasi-factual. It’s ever-mutating. It’s also resistant to a media landscape that capitalizes on the cheap currency of authenticity.

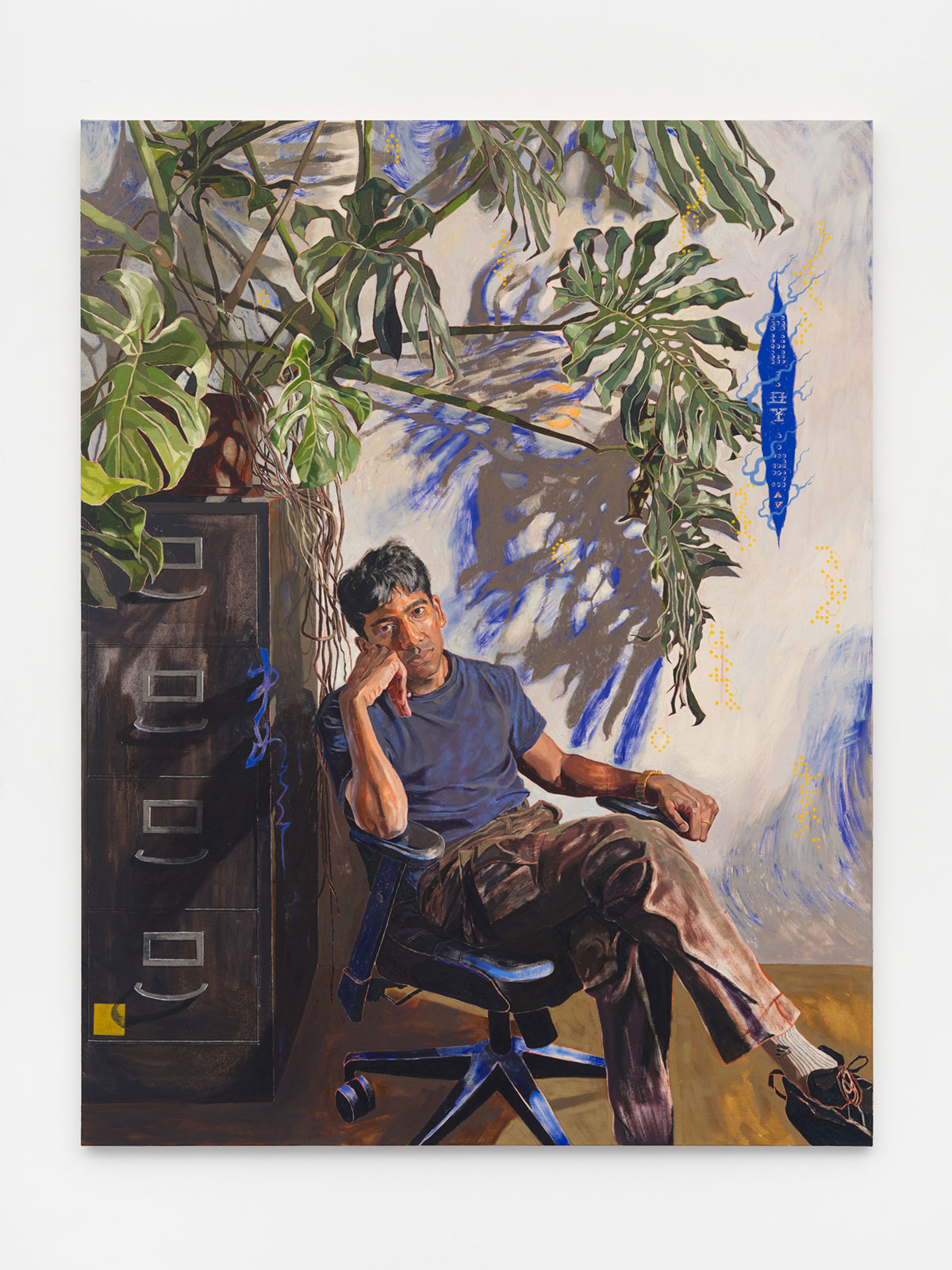

I first met yi Hou on a windy morning two years ago in Brooklyn. His show at the borough’s main museum, East of sun, west of moon, had opened two weeks prior. In the afternoon, he would participate in an artist-led staging of television news there. The producers had told him not to wear black. He came in Salomon sneakers, Wrangler jeans, and a quilted leather jacket, all black, save for a tight T-Shirt a few shades shy of obsidian. His jet-black hair was spiked, except at the widow’s peak, where it flattened against his forehead in a perfect triangle. In this show’s Self-portrait (25), aka: The beat of life (2024), he looks exactly the same. Sitting on a four-legged stool, his hands on his thighs, the artist stares straight ahead. A blank scroll unfurls behind him, enshrining this imperial portrait of Brooklyn cool.