In this portfolio of never-before-exhibited images from Document’s Fall/Winter 2024–25 issue, the late artist reveals fractured lines of humor, submission, and solitude

Nobody speaks. Poof, his red clown wig pulled into two buns, whimpers when the top-hatted Pile Driver threatens to sodomize him with freshly husked corn. Skank, her hair a mop of twisted rags, cackles. Josette screeches as M’Lord whips her bottom, drawing blood. Golden Rod appears intermittently with the sound effect equivalent of “glow”—an auratic, revelatory hum that exists only in the movies, which if I knew how it was produced would cease to signify “glow.” Language has no use in this underworld, just knives and licked lips, shackles and Vicks VapoRub.

Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #36 (Vice Anglais) (2011) was one of the last films Mike Kelley created before his death by suicide the following year. He began the EAPR video series—an outgrowth of his 1995 Educational Complex sculpture—in 2000, and he intended to follow number 36 with a few hundred more until he hit 365. The 25-minute live-action piece follows the previously described five characters as they wordlessly enact or accept various forms of violence, and it is partly inspired by Kelley’s fascination with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the English founder of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

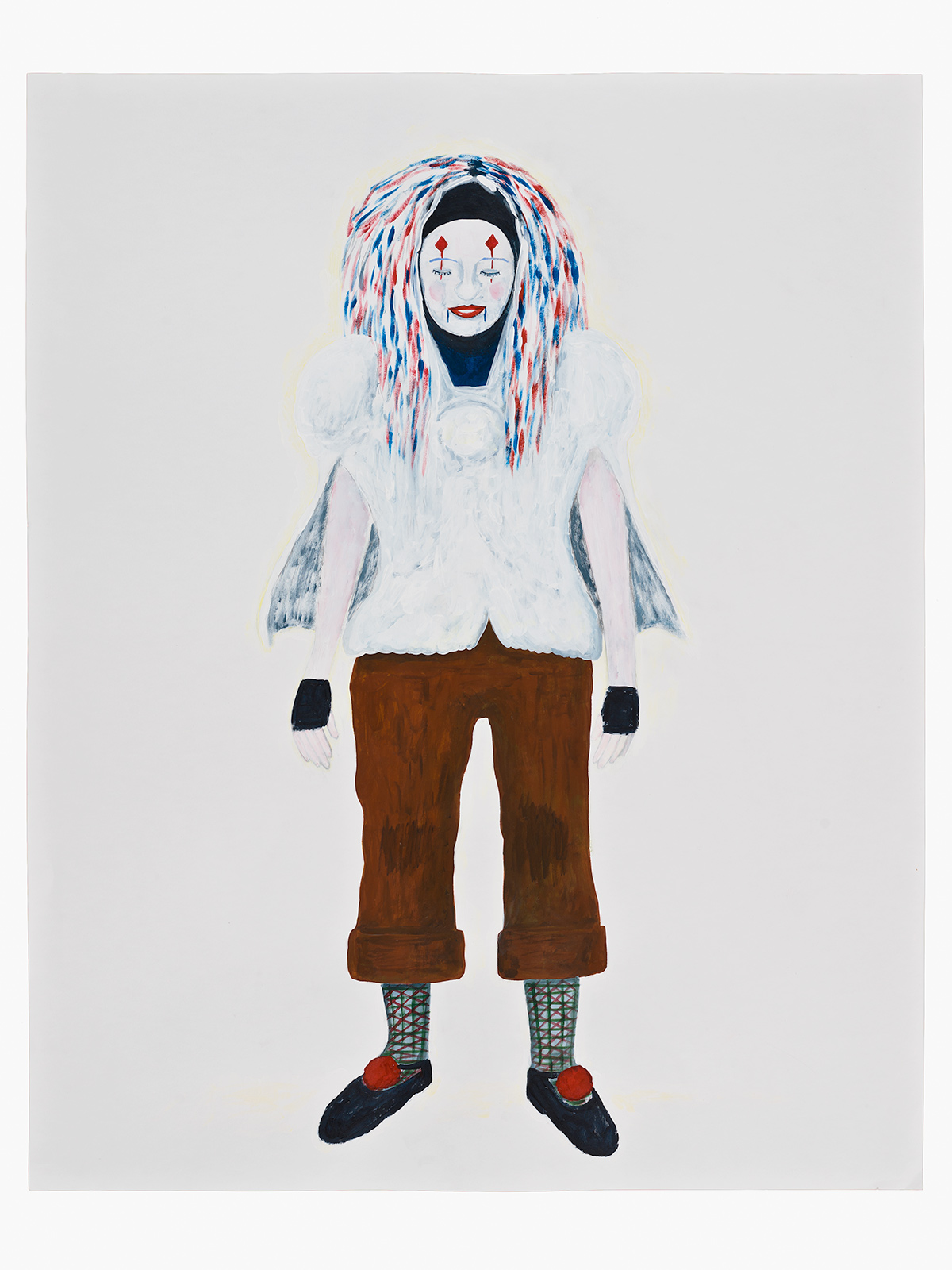

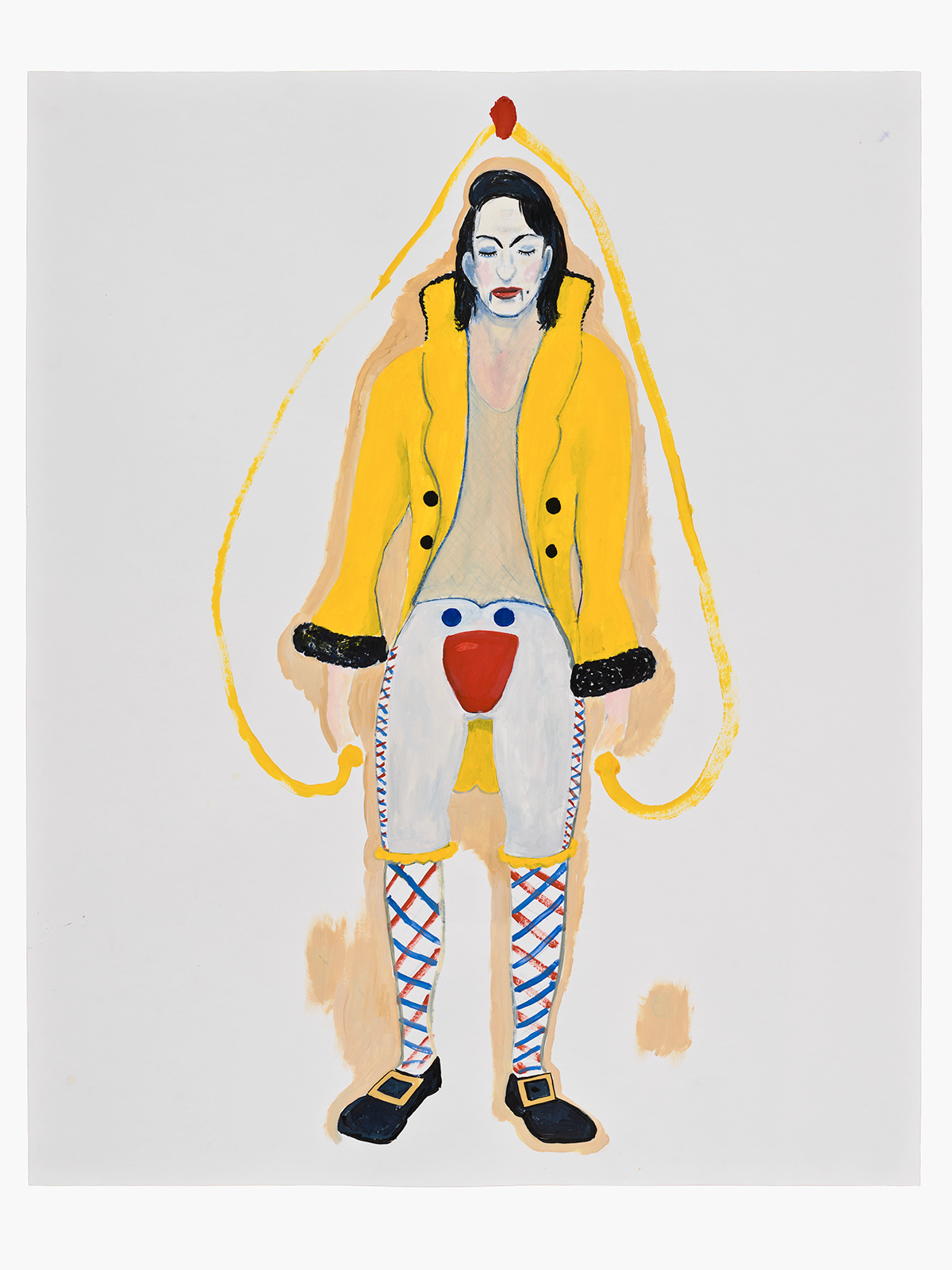

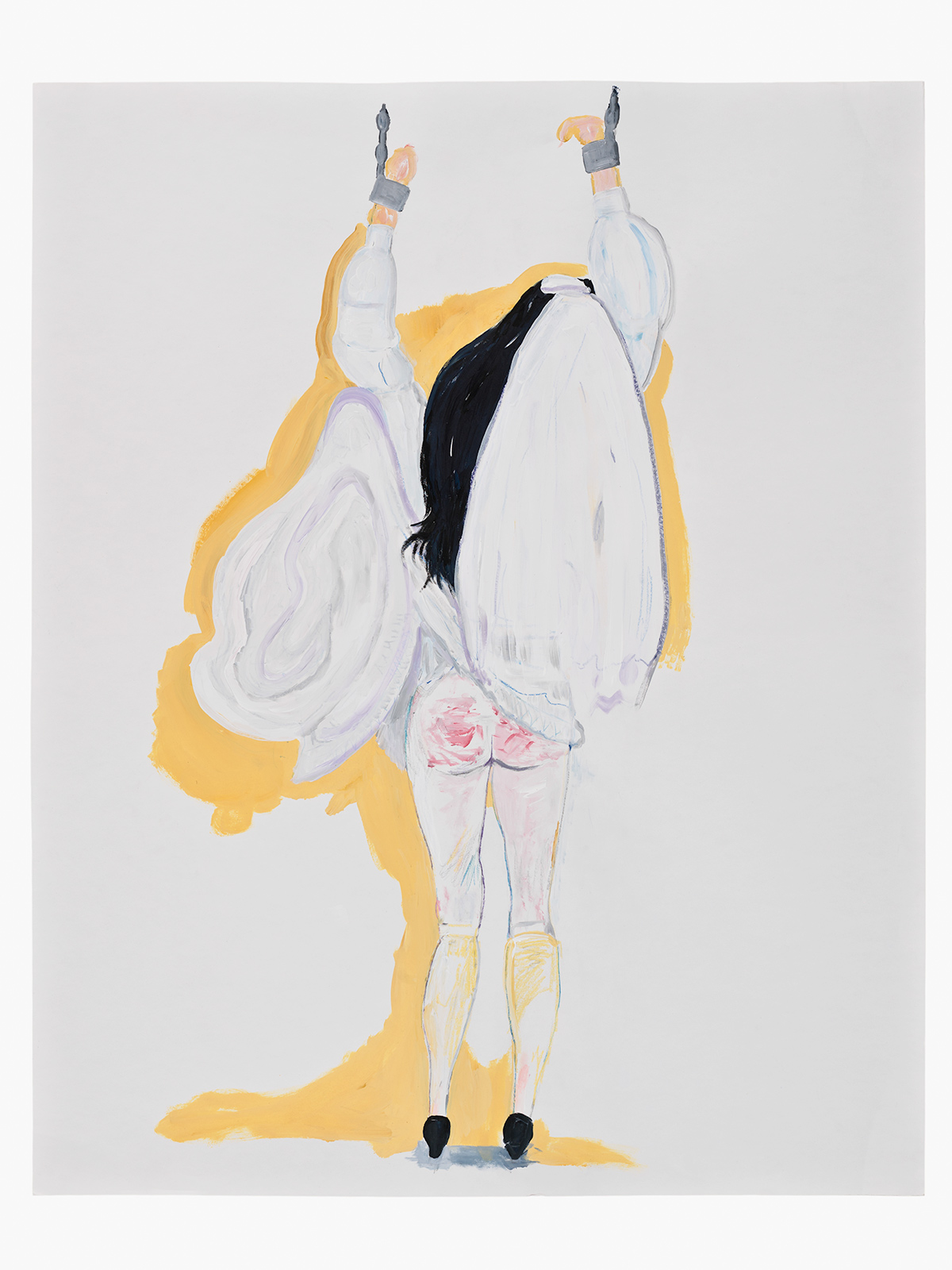

For the costumes in the film—as initially sketched in these 40-inch-tall character study paintings, which appear publicly for the first time in Document and will be exhibited at Hauser and Wirth in London in 2025 to coincide with the artist’s retrospective at the Tate Modern—Kelley looked toward high school yearbooks to gather references. He wanted a photo “stockpile” that could be “mundane,” he explained to Dennis Cooper in a 2000 interview about the first video in the series. But Kelley’s images of the mundane weren’t typical headshots. “I only picked the ones that were extremely carnivalesque, that weren’t normative. I didn’t pick sports unless they were wacky sports. I chose artsy stuff or Dress-Up Day or hazing rituals. Pictures where, when you look at them, you don’t know what’s going on,” he said. “You just know that it’s this kind of free moment in an authoritarian system—a moment that transgresses the boundaries but that’s completely allowed, even sanctioned by the system.”

The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan—who, according to one French journalist, had the whimsical habit of dancing with a “bushy ginger-colored wig”—described a prelinguistic “Imaginary,” an inchoate stage where the child pulses boundaryless with desires and sensation; the child exists as an undifferentiated sensuous field to whom there are not yet others because there is not yet a self. The child passes into the “Symbolic,” mediated by language, through the Mirror Stage, where an image of itself coheres, or, it being a reflection, an image coheres the self, the self already as other. “I knew by the time I was a teenager I was going to be an artist,” Kelley said in 2005. “There’s no doubt about that. There was nothing else for me to be.”

“When I was young, if you wanted to really ostracize yourself from society, you became an artist,” Kelley said three years later. To put it reductively, for Lacan, language is something that happens to us, a reckoning with social norms and histories that places screens between our selves and senses, and our capacity to express them and relate to one another. As EAPR #36’s grown-up characters shed language, the boundaries between them become only clearer: Why else would they need to taste the other’s blood except to affirm it is the other’s?

The class clown disrupts the classroom’s status quo and in doing so—by pointing to the arbitrariness of its rules—affirms its punitive power. But Poof is no class clown. He doesn’t disrupt; he abides. He rests on the boulder and awaits his punishment. (When we can assume he is being penetrated, we instead see Pile Driver arranging and destroying cut flowers.) Why does Poof deserve this fate? We don’t know. Poof’s very identity is his to-be-punishedness.

Kelley obsessively tackled educational institutions across his practice, going so far as to call his student training “abuse” and the “originating trauma” of his life. “Class hatred is what fuels me,” he said, referring to a different type of class, but one no less bound by an apparatus of discipline. M’Lord (possessive pronoun baked in!) doesn’t smile as he bludgeons Josette’s shapely ass. His arch, white-painted face barely rises to a smirk. We have no sense that Josette in her wedding dress has broken any rule in this “authoritarian system.” M’Lord’s aristocratic disinterest reads less as sadism (where is the pleasure?) or insanity (where is the loss of control?) than the automaticity with which dominant classes violate working bodies.

In 2005, EAPR numbers two through 32 were shown as an expansive sculptural video installation which Kelley called Day Is Done. The doneness of the day usually refers to leaving work or school, yet the word “extracurricular” in the installation’s composite films nearly negates the possibility of completion: By describing itself as “extra” to the curricular mandates, it affirms the centrality of those mandates. It is a fate without escape, “a moment that transgresses the boundaries but that’s completely allowed.” The same year Kelley presented Day Is Done, he remarked in an Art21 interview that when he started his stuffed animal sculptures, people immediately connected them—without his intent—to child abuse. So he followed suit. “I have to make this about my abuse. About everybody’s abuse. This is our shared culture,” he said. Rather than refuse the hazing language of the art press, Kelley adapted, expanded.

In his interview with Cooper, Kelley explained that the EAPR series began by thinking through a project on “modernist utopian architecture”—the 20th-century projects of achieving social liberation through a “unifying aesthetic system” that definitely didn’t pan out. For EAPR #36 (Vice Anglais), Kelley was in part intrigued by how the countercultural expressions of the Pre-Raphaelites—another group who sought a unifying aesthetic approach—related to the US countercultures of his youth. But in EAPR #36’s chthonic perversion of The Breakfast Club, aesthetic chaos prevails: a dirty woman in a wedding dress, a clown in what might approximate a football uniform, a European lord with a sportswear codpiece. Like the “types” of a US high school—jock, popular girl, prep—we have a sense these costumes are meant to stand in for identities, yet they are sullied, incoherent. Their wearers don’t articulate their relationships to one another with words but by giving and receiving violence; these power structures emerge as the true source of their identities.

Among the four aims of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood that Rosetti recorded was “to sympathize with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote.” But to showcase the abuse of this learning, Kelley must appropriate the “conventional and self-parading,” must show the emptiness behind the heartfelt costuming of adolescent effusion by playacting teens or would-be utopians. To be an artist in Kelley’s words is to be apart from the world, not to be superior to it—to broadcast proclamations—but to see it more clearly, to speak wordlessly of our shared culture, and to hope for recognition.

In Charles Baudelaire’s 1869 prose piece “The Old Showman,” the narrator ambulates through festivities thronged by jugglers and sunburned clowns and animal trainers. “On holidays, I think, people forget discomforts, labors; they become like children,” he muses. “For the child, it is time off, with the horror of school looming in 24 hours. For the adults it’s an armistice declared with life’s malicious powers, a breathing-space in the universal struggle.” As he wades through the “lights, dust, cries, joy, tumult,” he alights on a booth where he catches “sight of a poor showman, as if in shame self-exiled from all these splendors, bent, worn, decrepit, a human ruin, up against a post of his hovel.” The showman’s distress, Baudelaire writes, is “all too explicit.”

Amid “joy, profit, debauchery [and the] certainty of tomorrow’s bread” exists “absolute misery—misery decked out—to complete the horror—from the ragbag of comedy, a contrast introduced by necessity, not art. He, the miserable, was not laughing!” But nor does the poor showman cry or beg, and it is this that horrifies the narrator. “He remained mute and immobile. He had given up, surrendered. His fate was sealed.”

A sadness overwhelms the narrator, a sadness that at first mystifies him, until he realizes that in the mute old showman he sees only himself: “the old poet without friends, without family, without children, brought down by misery and public ingratitude, into whose booth the forgetful world no longer wishes to enter.”

Around nine minutes into EAPR #36, the stern M’Lord bends to observe a purple-lit resin city kept beneath an oversized bell jar. His face glows as his nose nears the glass. Other characters soon join. Kelley had a penchant of mixing his various bodies of work, and this prop appears to be one of his Kandor sculptures, Kandor 10B (Exploded Fortress of Solitude) (2011), from a series he embarked on in 1999 up until 2011, and which were among the last works exhibited during his life. The title refers to the alien city on Krypton where Superman was born, which the hero believed to have been destroyed along with the rest of his home planet. He later discovers his birthplace still exists, shrunken down and preserved in a bottle by supervillain Brainiac. An identity crisis ensues for the already double-identitied Superman. Has his life been a lie? Does he have a home? After defeating Brainiac, Superman retrieves the bottled Kandor and safeguards it in the Fortress of Solitude, his secret hideaway—most often but not exclusively depicted in arctic contexts—that is doubly his impossible, irretrievable home: a place to escape with no escape. Conflating the two locations—the place of origins, the place of isolation—collapses two forms of exile: forced and elective. It also conflates identity formation and architecture—self-discovery and loss of self. Kelley’s reconstruction of the fictional locations exemplifies his self-ostracization as well as his commitment to make an art that opens toward society’s collective abuse. In the gallery, we can all become like Superman: disidentified and alone.

I am fairly certain that in EAPR #36’s dungeon-like set is another Kelley sculpture, Exploded Fortress of Solitude (2011), which is a lithic pyramid that glimmers like a sliced, carnivalesque geode. In its destruction (it is already “exploded”), we find the beauty of sculptural completion. The fractured world, the hollowed self, the everythingness. In a 2011 exhibition itself titled Exploded Fortress of Solitude, the set of EAPR #36 was exhibited in blurry circularity as an installation called Fortress of Solitude with the film projected upon it.

Facing the violence and dissolution of these exploded artifacts and violent videos, this horror and beauty, these little homes, these infinite mirrors, these luminescent showman’s hovels—whether in Kandor upon planet Krypton or smuggled away in the tundra or the gallery as a Fortress of Solitude—we can’t help but visit them, these gorgeous, cursed sites, again and again in each posthumous exhibition, as if attempting to enter some impossible place, an impossible place that—in its endurance—has declared itself already gone.