For Document’s Fall/Winter 2024–25 issue, Whitney Mallett talks to co-editors, writers, and collaborators of the legendary publisher of theory and fiction

When you clock that small “e” couched in parentheses on the spine of a book, do you feel something shared between you and its reader? At once unmistakable and unassuming, this perfect signifier, the “e” in Semiotext(e), is a signpost marking a sensibility that’s been a lightning rod through English-language publishing since 1974. Bringing to readers books that feel both urgent and long-lasting, Semiotext(e) is a phenomenon in the worlds of theory and literature. An independent press that’s remained nimble yet impactful through context-savvy taste and constant reinvention. While their offerings span economics, satire, science fiction, activism, and memoir by writers idolized and unknown, something coheres this range and bridges the many changes over its five-decade history. Publishing industry veteran Ira Silverberg encapsulates the palpable unifying sensibility: “Whatever the crisis is on the ground or in the heart is not being sugar-coated.”

If the Semiotext(e) story was a movie, it would require an ensemble cast with cameo parts for mythic beatniks, artists, and philosophers: William S. Burroughs, Jack Smith, Gilles Deleuze, and Michel Foucault were all published by Semiotext(e) in the mid-’70s when it was a journal. Maybe Kristen Stewart could even have a small role playing herself (she read from her favorite book, the Semiotext(e)-published Heroines by Kate Zambreno, at a Chanel event last year). The three leads, however, would be: Sylvère Lotringer, the French theorist and co-founder who passed away in 2021 at age 83; Chris Kraus, who today co-edits the press, an American filmmaker turned writer who grew up partly in New Zealand and was married for a period to Lotringer; and Hedi El Kholti, the other current co-editor, a Moroccan-born writer and visual artist who’s managed most of the day-to-day operations since the early 2000s.

The three have run the press in America since its inception. First in New York City and then Los Angeles, where Kraus and El Kholti live presently. The press is celebrated for bringing French theory to the US in the ’70s and a cohort of outsider writers, many of them women, to the fore in the ’90s. While Semiotext(e)’s history was woven into many of the remembrances published when Lotringer passed away a few years ago, this year’s milestone 50th anniversary came quietly and without much fanfare. About Semiotext(e)’s legacy, El Kholti says, “I try generally to not think too much about it.”

“It’s not often that a Semiotext(e) book becomes a bestseller. But how it’s happened when it’s happened has been entirely unpredictable.”

By avoiding the nostalgia-bait that kills forward momentum, Kraus and El Kholti have balanced inheritance and instinct in stewarding the press’s current era. Kraus explains, “The press has become, weirdly, simultaneously more professional and established but also more open and experimental.” A 20-year-old re-editioned novel about a network of resentments finds its place next to a memoir about insomnia or a manifesto on conspiracy. (Gary Indiana, Do Everything in the Dark; Marie Darrieussecq, Sleepless; and the anonymously authored Conspiracist Manifesto, respectively.) A lot of what Semiotext(e) publishes is anti-capitalist, queer, or French books translated into English for the first time. “I suppose the press keeps changing as things are absorbed by the mainstream culture,” says El Kholti. “We publish a certain type of book. It gets noticed. Other presses start competing for it. We can’t pay larger advances, so we move on. We always have to find things no one else is doing.” One of their most hotly anticipated releases this fall is a collection of Amazon reviews by the late poet Kevin Killian. Last year they published a diary written by a 14-year-old in 1979. In a time when culture feels overwhelmingly predictable to even the least curious among us, what Semiotext(e) publishes remains surprising.

The story of Semiotext(e) starts with Lotringer. Born in Paris to Polish-Jewish immigrants at the precipice of World War II, he eventually found his way to New York in 1972 trying to catch up with Columbia’s student rebellion. Though the protests he’d been seduced by were mostly over by the time he arrived, the university became a stage for a landmark conference he organized in 1975. Titled “Schizo-Culture,” it was interested in madness and brought together American artists like John Cage and William S. Burroughs with French post-structuralist thinkers like Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Jean-François Lyotard, alongside psychiatric patients, formerly incarcerated people, and activists. Politically significant, “Schizo-Culture” also had the downstream effect of spawning an explosion of college cultural studies programs.

Lotringer contended he didn’t launch Semiotext(e) as much as it launched him. While he co-founded the project with Susie Flato and John Reichman, it was Lotringer who got the outsized reputation as the man who brought French theory to America. Charismatic, brilliant, and perverse, he had the personality and persona for a label like that to stick. Lore includes his penchant for black leather and that many of his philosophy students at Columbia danced at a topless bar in Chelsea. Through the 1970s and ’80s, Lotringer published the Semiotext(e) journal, and, in 1983, Semiotext(e) expanded into publishing books—works on philosophy, politics, and postmodernity. The first was an English edition of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulations.

Kraus and Lotringer met a few years after that and the two started dating and eventually married. Kraus had an idea that Semiotext(e) should also start publishing first-person fiction. “I begged Sylvère to let me do it,” she recalls. “I was still making films and hadn’t started writing yet, but my closest friends were writers and I had the feeling that their books urgently needed to come out.” She started the imprint Native Agents in 1990. “Ann Rower hadn’t published any books, Eileen Myles’s books up until Not Me had been mimeographed and stapled. And then hearing Cookie [Mueller] read at St. Marks when she was ill and hearing no one wanted to publish her book of stories just devastated me.” Kraus’s Native Agents imprint has existed ever since and continues to platform new voices in fiction like Natasha Stagg and Nate Lippens. The narratives it favors often mix candor and confession with class consciousness, structural analysis, or art criticism, making it a logical complement for the theory the press has published from the start. Kraus adds, “I guess I was hoping to piggyback on Sylvère and Semiotext(e)’s reputation to do something, make some kind of mark.” Eventually, in 1997, she published her first novel on the imprint, I Love Dick, today maybe the most famous Semiotext(e) book of all.

Native Agents pioneered a kind of first-person writing that gets called autofiction these days, though Kraus and many of the writers she’s published reject the term. “When I started Native Agents, it was with the idea of introducing a first-person (mostly) female fiction that would not be branded ‘memoir’ or ‘autofiction.’ There are many literary traditions where the writer is extremely present in the text— the absence of the author seems more of an anomaly.” Around those first years of Native Agents in the early ’90s, Semiotext(e) organized a tour across Germany, where each night the authors they brought over from America would read live, mostly at art centers. Lotringer and Kraus conscripted Myles, Rower, Kathy Acker, Richard Hell, and Lynne Tillman to join the lineup. “Here we were, this rather unusual representation of American writing,” Tillman recalls with a laugh. “What we had in common was attitudinal. We all had a grievance with the mainstream and the complacency of American life.” Tillman remembers one evening when the first-person narrative approach was not well-received. “They were asking us about our politics. To them, sexual politics absolutely did not stand as politics; this was American ridiculousness. I don’t think any of us handled the question well. It was a disturbing night.”

Back then, even in America, there wasn’t the same consensus around how the personal is political as there is today. Still, the Native Agents books never shied away from first-person reckonings with abortion, mental illness, anorexia, rape, and rejection when these subjects were still considered too feminine, superficial, or embarrassing to write about seriously (and they were presented without the pat sentimentality that still is often a requirement for mainstream platforming). I Love Dick narrates a love triangle between a character named Chris (who resembles Kraus), her husband Sylvère (who resembles Lotringer), and another theorist named Dick (who resembles Dick Hebdige, the author of Subculture: The Meaning of Style). All of them come across more humiliated than heroic. The book was a sleeper hit, its sales taking off 15 years after it was first published, this rediscovery by a new generation of women a testament to how Native Agents was ahead of its time.

The initial Native Agents author list had been really New York-centric, but that changed when Kraus and Lotringer moved to LA in the early ’90s. The press also changed when the couple encountered Hedi El Kholti, who’d eventually come to join them as a third editor. El Kholti had relocated to LA around the same time. He worked in the film industry in Hollywood for a few years, as he had in France, before deciding to go back to school to do a BFA at ArtCenter College of Design. “I met Sylvère at ArtCenter in Pasadena and worked with him on a school publication, which took a couple of years to manifest,” recounts El Kholti. “Like everything Sylvère did, it was on its own timeline. He was never in a rush. We saw each other a lot around that time and became friendly.” El Kholti’s visual art practice centers on printed matter and collage, but back then, he was also publishing books with his partners at Dilettante Press. He started working on a multi-year project for Sylvère, Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs, 1960–1997. “This is when I met Chris. I remember going to a Thanksgiving at Crestline, near Lake Arrowhead, where they had a house.”

Through the 1990s, Semiotext(e) kept chugging along, publishing fiction and theory by writers like Paul Virilio, David Rattray, Shulamith Firestone, and Michelle Tea. Some of their biggest titles included Still Black, Still Strong from 1993, featuring the stories of Dhoruba bin Wahad, Assata Shakur, and Mumia Abu-Jamal, and the anthology The New Fuck You: Adventures in Lesbian Reading from 1995, edited by Eileen Myles and Liz Kotz. Semiotext(e) was a home for books you couldn’t imagine anywhere else. But as the millennium came to a close, Lotringer and Kraus saw the writing on the wall. Professionalize or perish. In 1998, the last issue of the journal was published, and in 2001, Semiotext(e) struck a distribution deal with The MIT Press, ushering in a new era. “People often focus on the distant past with me and Sylvère, but everything changed when Hedi became a co-editor,” recalls Kraus. “Chris put up some money and I was hired part-time,” recounts El Kholti, who had transferable experience from working in accounting in the film industry. He started to streamline operations and increase how many books were published each year. “There was no real plan, particularly at the beginning, beyond republishing the iconic issues of the magazine—‘Schizo-Culture,’ ‘Autonomia,’ and ‘The German Issue.’ I never thought it would last this long.”

“Even when Semiotext(e) books tackle urgent political issues, their approach is often poetic and deeply human.”

One of the earliest books that Semiotext(e)/Native Agents published in that new era was the 2005 novel Reena Spaulings, authored by the art collective Bernadette Corporation. Semiotext(e) author Natasha Stagg recalls it was the first book from the press that she came across. “I got it from a friend visiting Berlin for the first time in college. She worked at a bookstore there. It opened up something for me,” she remembers. “The way it flows from topic to topic. The way it gets macro-micro without having a whole lot of transition.The temperament of the writing was exciting to me. It was something I wanted to emulate. I thought people should just be able to write like this. It felt like you were hovering around this character, as opposed to her letting you in.” Stagg’s first novel, Surveys, is similarly detached. She adds, “It’s very instructive how these books reach the right people at the right time in their lives.”

It’s not often that a Semiotext(e) book becomes a bestseller. But how it’s happened when it’s happened has been entirely unpredictable. Take The Coming Insurrection, which launched the press’s Intervention series in 2009. The slim volume was a translation of the ultra-left French collective The Invisible Committee’s call to arms, first published as L’insurrection Qui Vient two years before by La Fabrique Éditions. When the French edition was used as evidence in a high-profile trial against a group of alleged anarchist saboteurs known as the Tarnac Nine, Semiotext(e)’s English version ended up on Fox News. “Glenn Beck called it ‘the most evil book ever published’ and urged all his viewers to buy a copy,” says El Kholti, recounting the surreal endorsement. The book subsequently flew off the shelves. Other books hit the zeitgeist in ways El Kholti couldn’t have anticipated either. Four years after I Love Dick’s resurgence, it was adapted into a TV show. Andrea Dworkin was declared the prophet of #MeToo right when Semiotext(e) was publishing Last Days at Hot Slit. And the republication of Hervé Guibert’s AIDS novel To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life happened to coincide with Covid, renewing it with such urgency that it got reviewed by The New Yorker and The New York Times. “In this climate, the successes sustain the rest of the list, and they feel somewhat arbitrary,” remarks El Kholti.

Even when Semiotext(e) books tackle urgent political issues, their approach is often poetic and deeply human. “Some of the books we’re most strongly drawn to are ones that don’t separate personal experience from structural awareness and analysis,” Kraus says. She points to Heike Geissler’s Seasonal Associate, an exposé of labor conditions at Amazon, based on the author’s experience as a temp worker in a fulfillment center during the holiday season. “Seasonal Associate is a special book because Geissler didn’t journalistically ‘embed’ herself; she actually needed the job. She’s such a strong, intelligent writer— it’s kind of a miracle for the exploitative work conditions of Amazon to be experienced out of necessity and then so brilliantly expressed. Likewise, Jackie Wang’s book Carceral Capitalism is a work of scholarship driven by a passion that began with her brother’s incarceration.”

Semiotext(e)’s books continue to draw people in who then become friends and collaborators, like Janique Vigier, the head of the press’s publicity in recent years. “Since she’s a writer herself, Janique has the intelligence and subtlety to present the books on their own terms, free of any cheesy pitch,” explains Kraus. “She’s greatly enhanced the visibility of the press.” For Vigier, it’s the relationships that keep her invested. “I don’t know if I would do it if it didn’t keep me in regular touch with Hedi and Chris,” she says. “These are two of my good friends and it feels like this tether that I really value. They both have been good at building a little world.”

Kraus said the intention was never to be a “small” press. “Sylvère used to say about Semiotext(e) when it was still a magazine that you have to try and reach all of America in order to reach 5,000 people,” she recounts. “But the prospect of an office, an HQ, all the trappings of institutionalization are pretty horrifying, which is why it makes sense to continue on the scale we do.” And it’s this scale that affords them the opportunity to take risks. “One advantage of having stayed small and having very little overhead is that I don’t feel too concerned about one decision or another,” admits El Kholti. “The stakes are low enough, I don’t overthink things.” Rather than have a top-down idea of what aesthetic a Semiotext(e) book needs to be, he explains, “I see my role as managing the flux of desire that passes through us from our collaborators.” For Kraus, when deciding whether they should publish a book or not, it’s less about any particular criteria and more about urgency. She asks herself, “Does it feel like we have to do it?”

When Lotringer passed away in 2021, it was another instance of reinvention, where change led to reaffirming origins. “There was a moment when Sylvère died that I thought, What are we doing it for now? And what does it mean?” El Kholti recalls. “I realized we can still be in conversation with someone who is gone.” There are projects now that he takes on with Lotringer explicitly in mind, like a collection of writings by the Catalan psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles, whose clinic had an influence on the legendary facility La Borde. “Sylvère spent some time at La Borde and was really interested in institutional psychotherapy,” explains El Kholti. “He would be thrilled that we’re doing this book.” With every new manuscript, the project survives Lotringer and keeps him alive. Kraus adds that she’s “missing him but he feels present on an almost daily basis.” The “e” in parentheses at the end of Semiotext(e) was his idea.

Image Index

1. Left to right, top to bottom: Anne Rower, If You’re a Girl: Selected Stories 1985–2023 (2024), an expanded reissue of Semiotext(e)’s initial publication; the press has committed to reeditioning significant works. Nate Lippens, My Dead Book (2024), a republication of a novel of insomnia, loss, labor, and loneliness. Paul B. Preciado, Can the Monster Speak? (2021), a translation of Preciado’s controversial 2019 lecture to an audience of psychoanalysts, in which he challenges the field’s legacies of homophobia and transphobia. Eileen Myles, Not Me (1991), a celebrated depiction of ’80s New York and one of Myles’s first books not mimeographed and stapled. Kathy Acker and McKenzie Wark, I’m very into you (Correspondence 1995–1996) (2015), a collection of gossipy, philosophical, and sexy emails between the novelist and the theorist.

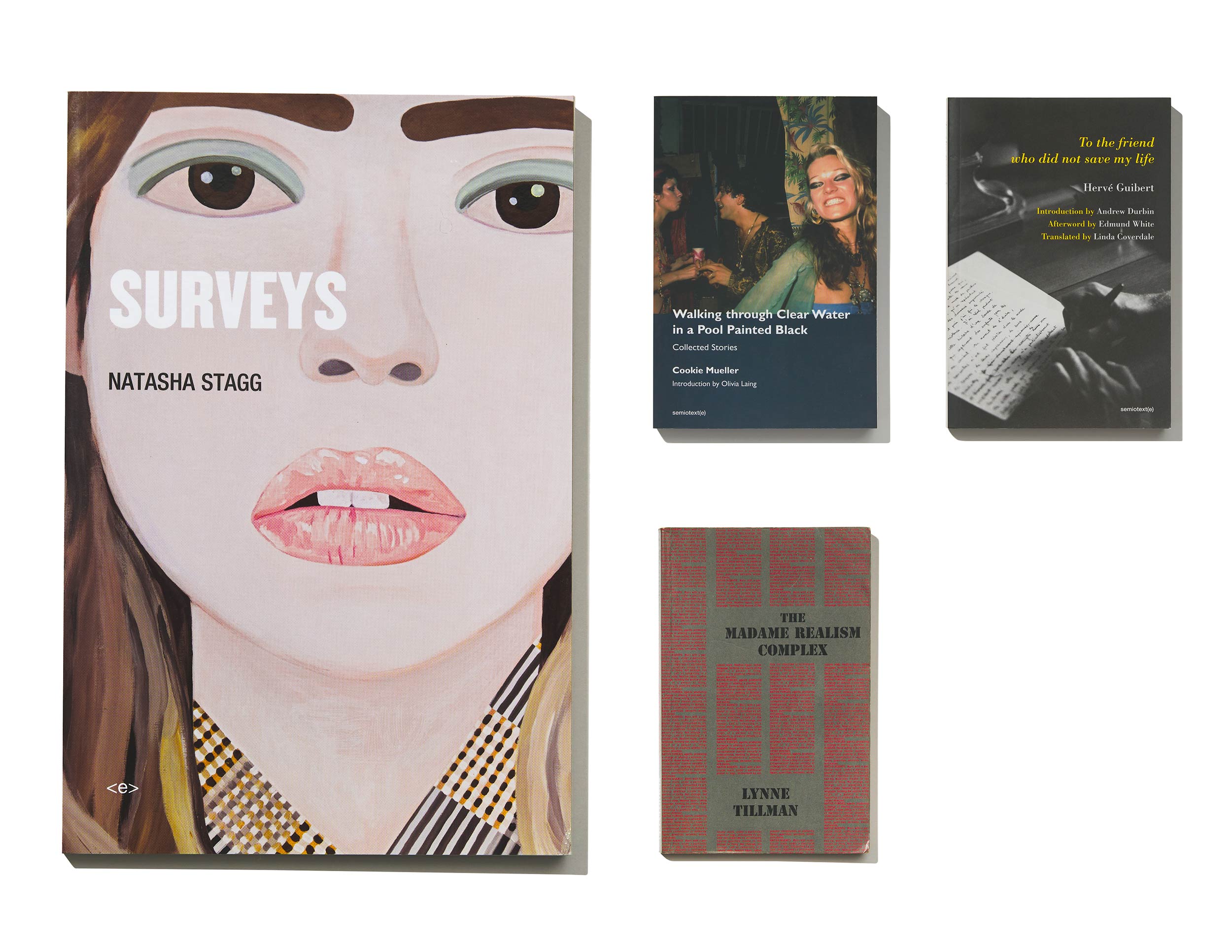

2. Left to right, top to bottom: Natasha Stagg, Surveys (2016), a debut novel that wryly riffs on the classic coming of age story. Cookie Mueller, Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black: Collected Stories (2022), the first collection of the actor and writer’s dozens of stories published alongside the contents of Native Agents’ original 1990 book of hers by the same title. Hervé Guibert, To the friend who did not save my life (2020), a republication of the French author’s acerbic and intimate AIDS novel, which was newly prescient when it hit shelves amid the Covid pandemic. Lynne Tillman, The Madame Realism Complex (1992), a short fiction collection and one of Native Agents’ earliest books.

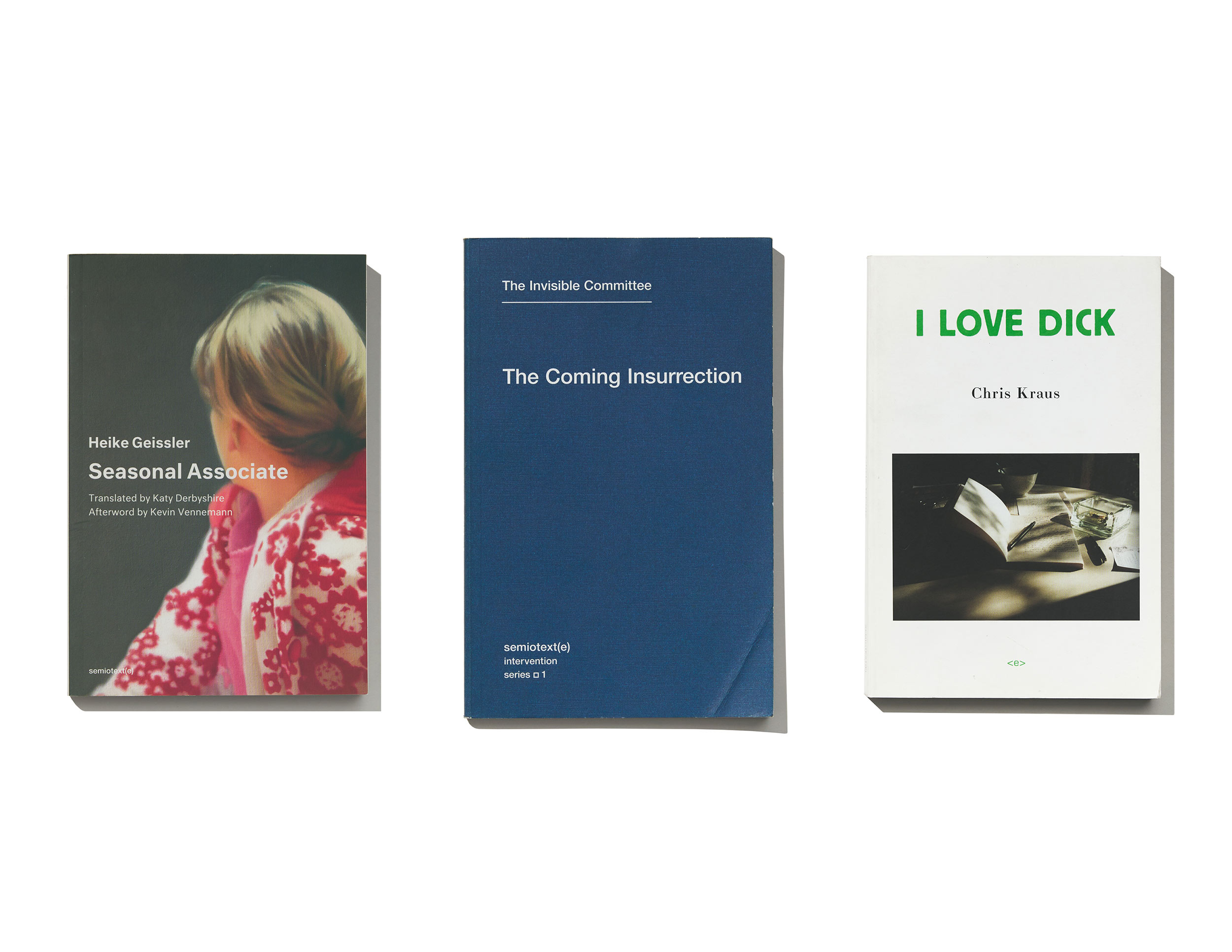

3. Left to right, top to bottom: Heike Gessler, Seasonal Associate (2018), a literary account of Geissler’s experience facing financial precarity and working in an Amazon order fulfillment center in Leipzig. The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (2009), a translation of the book that was used in in the controversial French trial of the alleged Tarnac Nine saboteurs and was described by Glenn Beck on Fox News as “the most evil book ever published,” causing it to soar in sales. Chris Kraus, I Love Dick (1997), an epistolary novel by the Semiotext(e) co-editor, which became one of the press’s most enduring classics when a new generation of readers rediscovered it in the 2010s.

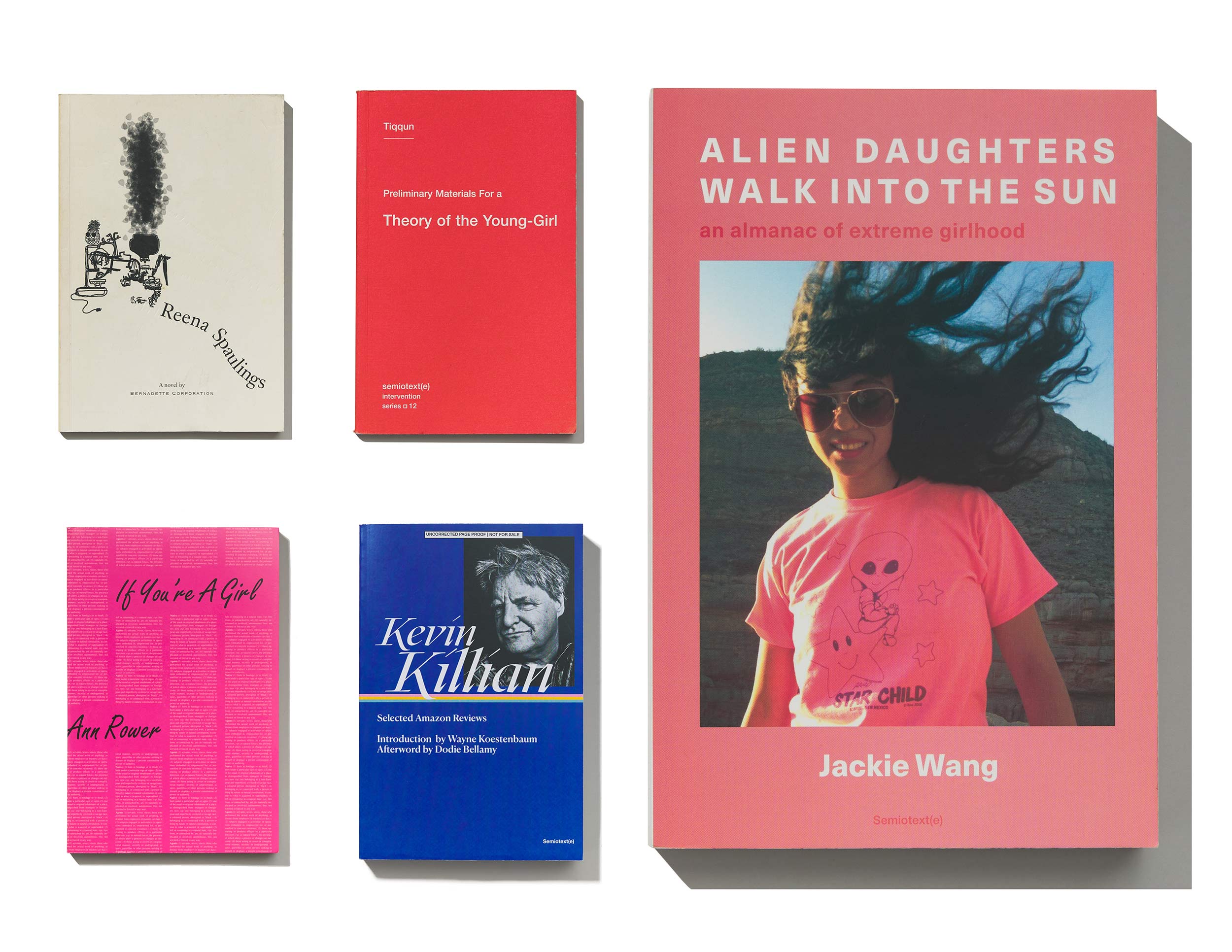

4. Left to right, top to bottom: Bernadette Corporation, Reena Spaulings (2005), a collectively authored novel that became an era-defining text bridging literature, fashion, and art. Tiqqun, Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl (2012), a translation from the French by Ariane Reinnes of the anonymously authored exploration of gender, media, and consumerism. Jackie Wang, Alien Daughters Walk into the Sun (2023), a collection of the poet and theorist’s early blog and zine writing spanning criticism, travelogue, essays, and weather reports. Anne Rower, If You’re a Girl (1991), a debut project by the author promotionally copy frequently describes as “the Eve Babitz of lower Manhattan.” Kevin Killian, Selected Amazon Reviews (2024), an anthology of the late poet and novelist’s funny and incisive public product reviews.

5. Left to right, top to bottom: Dodie Bellamy, When the Sick Rule the World (2015), a deft and lyric, manifesto-like genre-meld that proclaims, “When the sick rule the world, mortality will be sexy.” Kevin Killian, Fascination (2018), a triptych of memoirs about 20th century gay life on Long Island. Eds. Michael Bullock and Cesar Padilla, I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean De Lear (2023), a volume of the legendary punk musician and artist’s adolescent journals depicting sex and self-exploration. Dhoruba bin Wahad, Assata Shakur, and Mumia Abu-Jamal, Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors of the War Against Black Revolutionaries (1993), an activist document by jailed Black Panther Party members. Eds. Chris Kraus and Sylvère Lotringer, Hatred of Capitalism (2002), an anthology largely drawn from Semiotexte(e)’s early journal, which bridged French philosophy with US literature, art, and activism.