To accompany this exclusive fashion portfolio in Document’s Fall/Winter 2024–25 issue, Thomas is joined by actor and screenwriter Lena Waithe to unpack the art of dandy dress

When I was invited to interview the multidisciplinary visual artist Mickalene Thomas and the screenwriter, actor, and producer Lena Waithe for this fashion portfolio, I immediately began to think about what I knew about their personal styles. I clicked through hundreds of images in order to glean both the many similarities in their fashion choices and the distinct differences. Parsing through the photographs, I marveled at the discipline it takes to commit to a sartorial point of view, an almost priestly devotion to a “look,” a fashion uniform.

In practically every picture, Waithe—who has acted in shows and movies like Master of None (2015–) and Ready Player One (2018), wrote the movie Queen & Slim (2019), and created multiple series, including The Chi (2018–)—presents herself in suiting: exquisitely tailored jackets, trousers, and shirts accented in vibrant colors and by pattern play. She could easily be the subject of one of Thomas’s paintings, many of which are currently being exhibited alongside installations and photographs in the traveling retrospective All About Love, organized by the Broad Museum, the Barnes Foundation, the Hayward Gallery, and Les Abattoirs Museum. Often these subjects are women draped in flowing clothes, their poses drawing from references across art history and popular media, set against patterned, collaged environments that are composed with acrylic paint, sequins, and found media like linoleum and wood paneling.

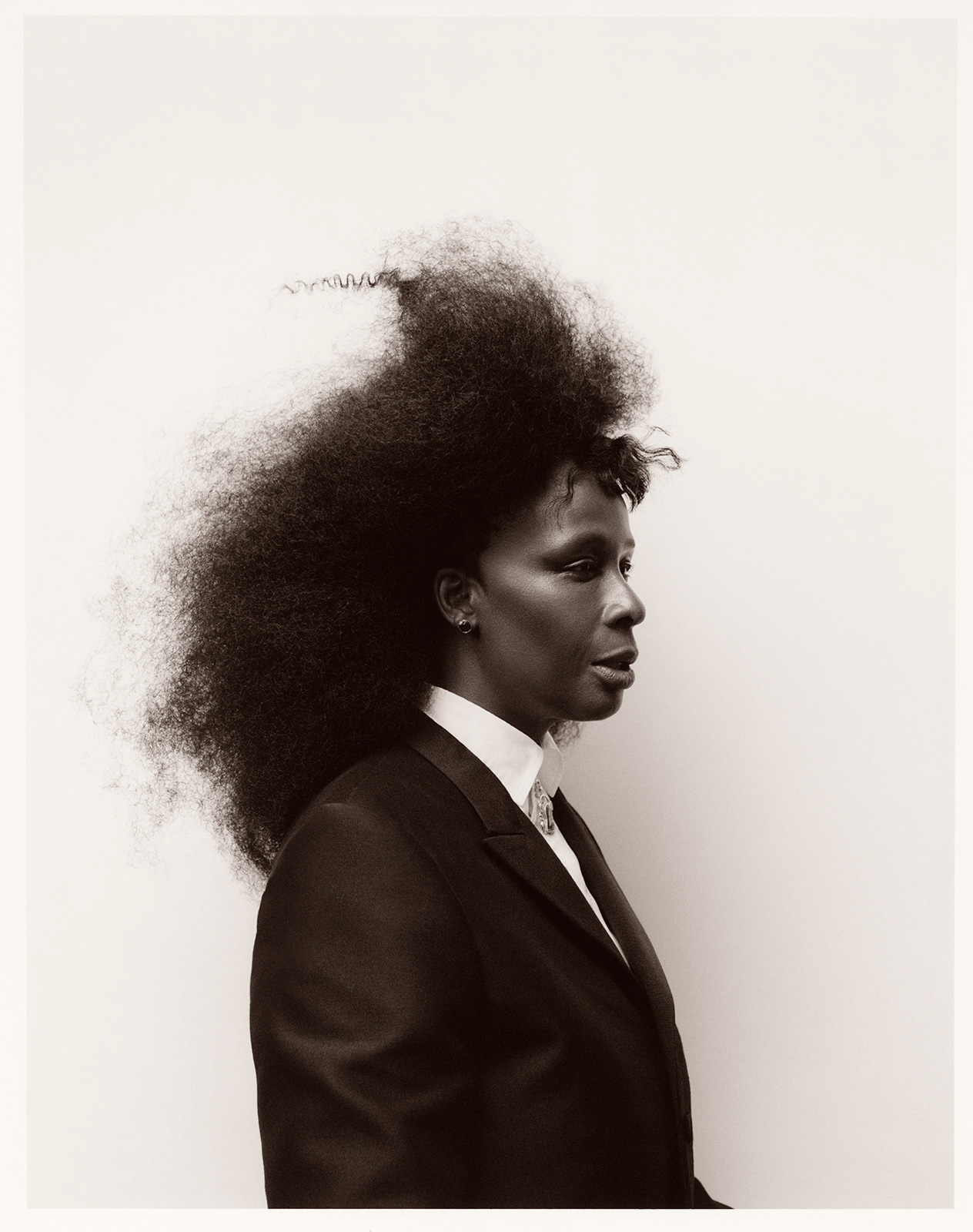

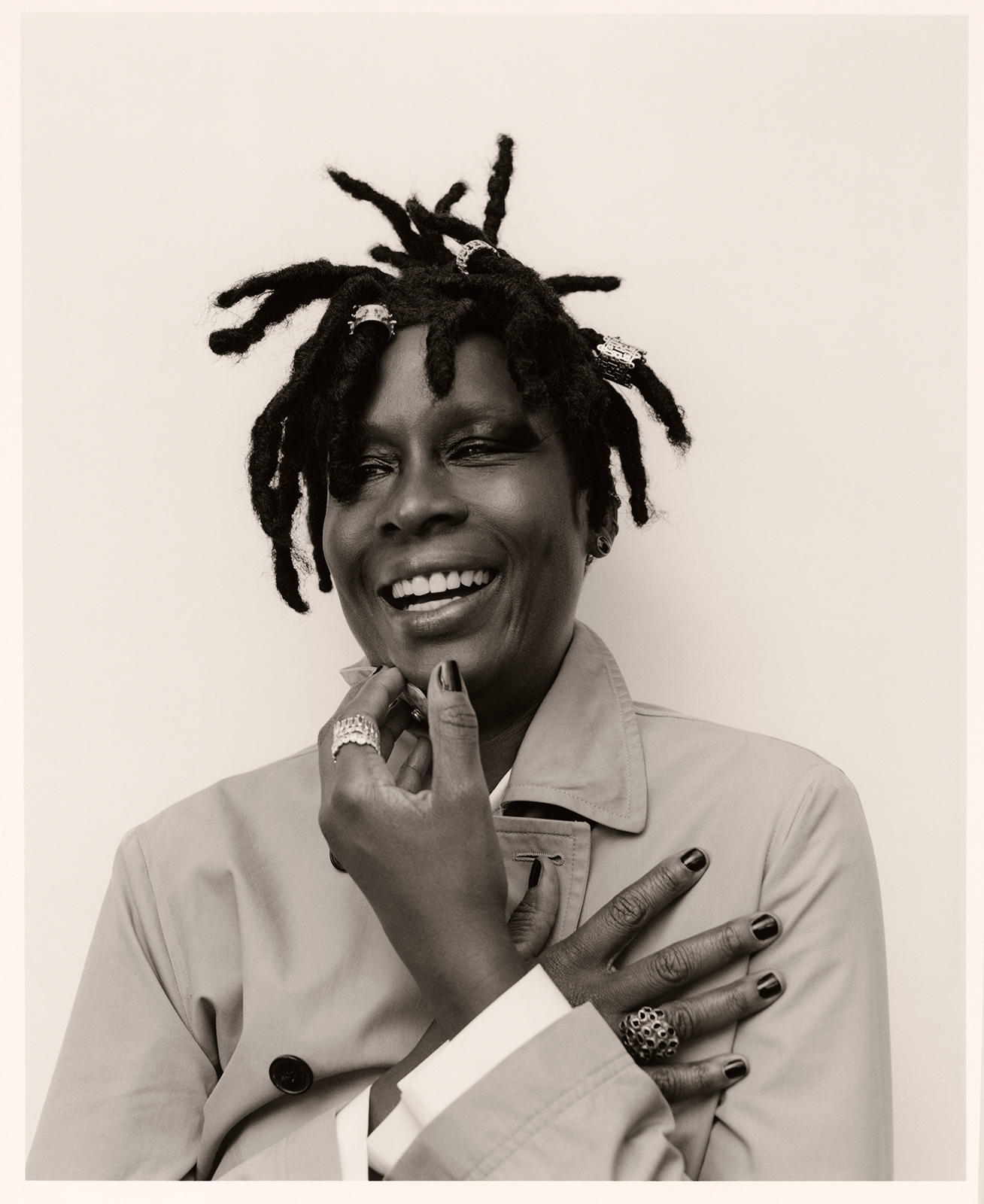

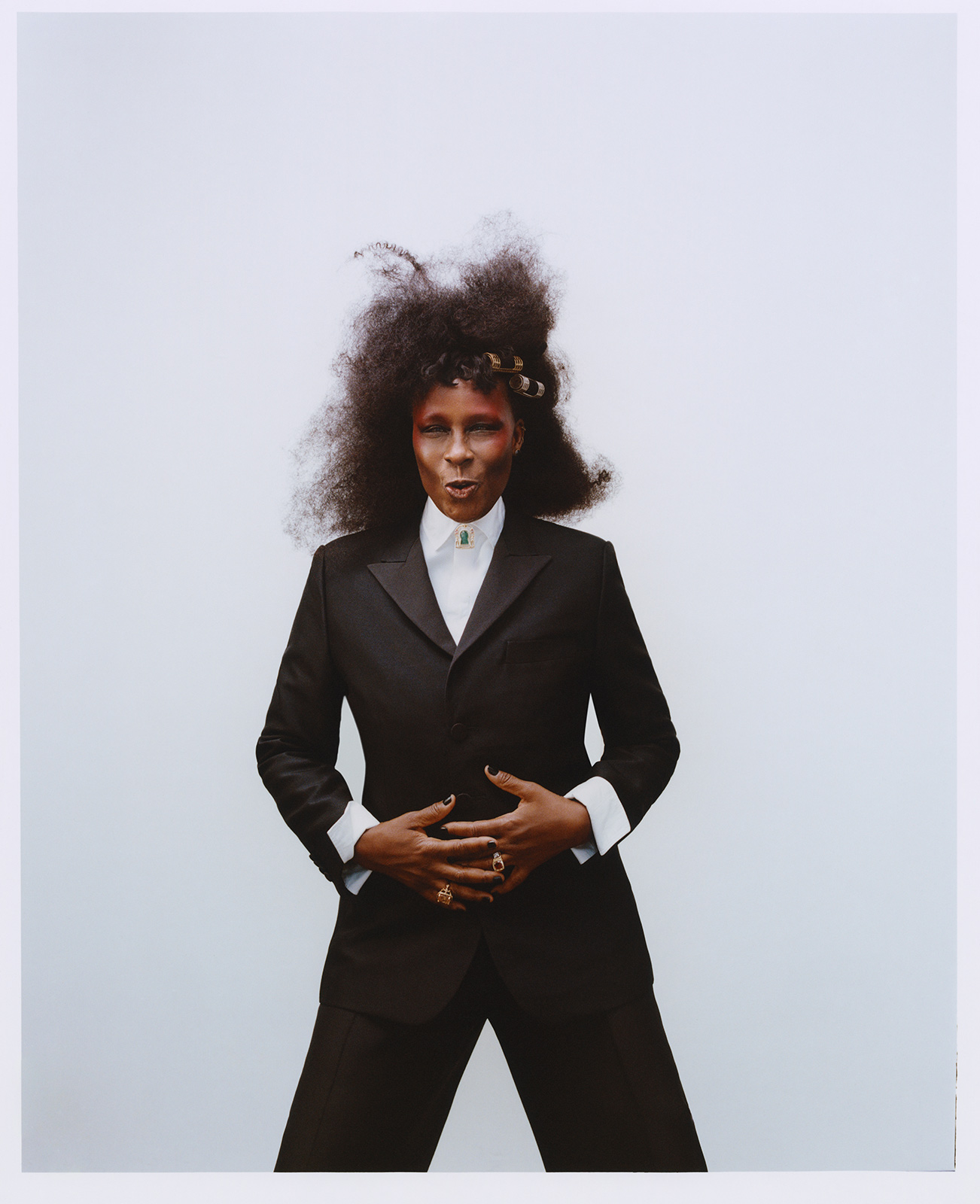

In her personal style, Thomas is known for her luxurious suits and avant-garde, androgynous silhouettes, always in a monochromatic palette of black or dark blue. Waithe favors a hip-hop-inspired aesthetic in her less formal dress.

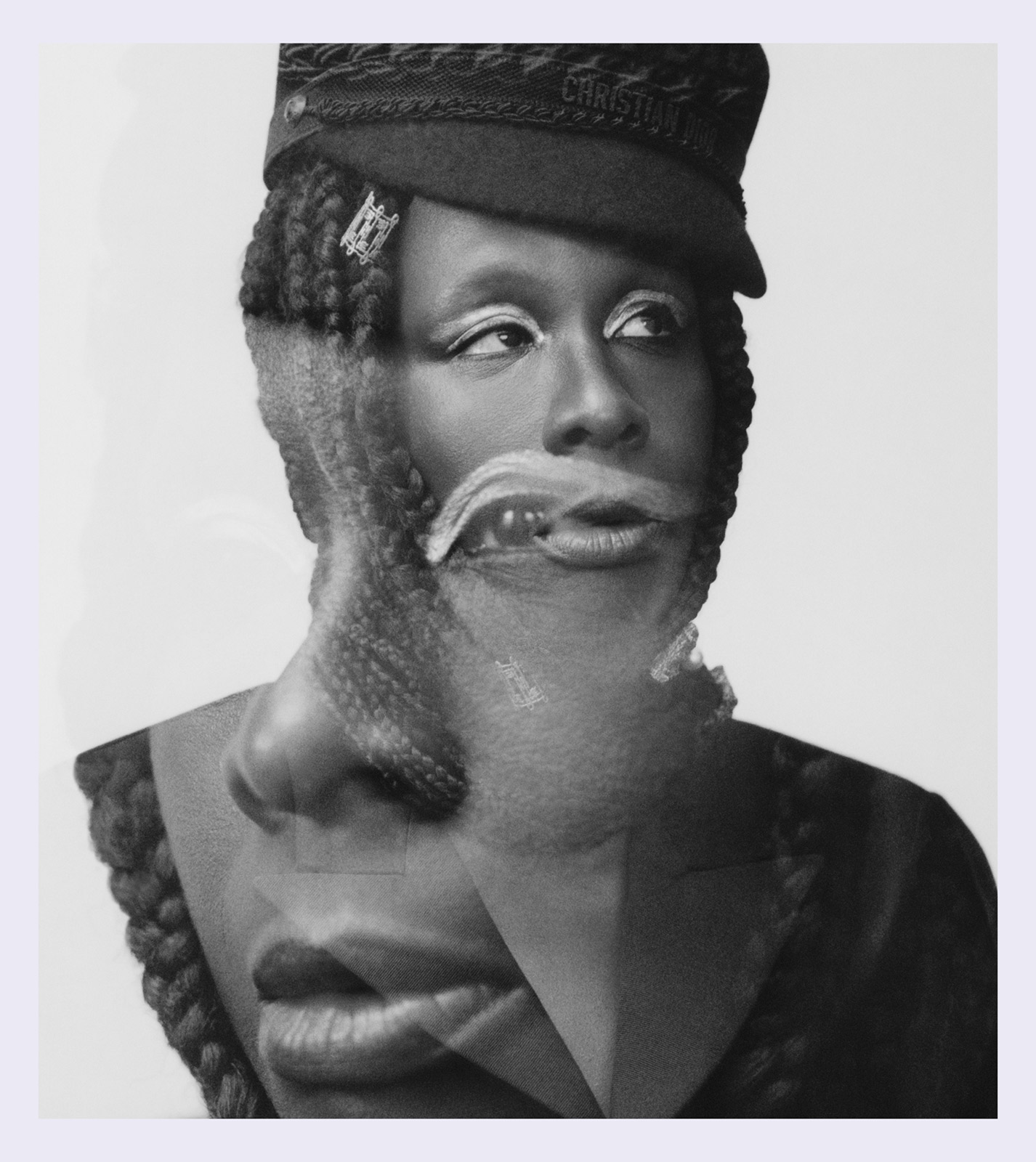

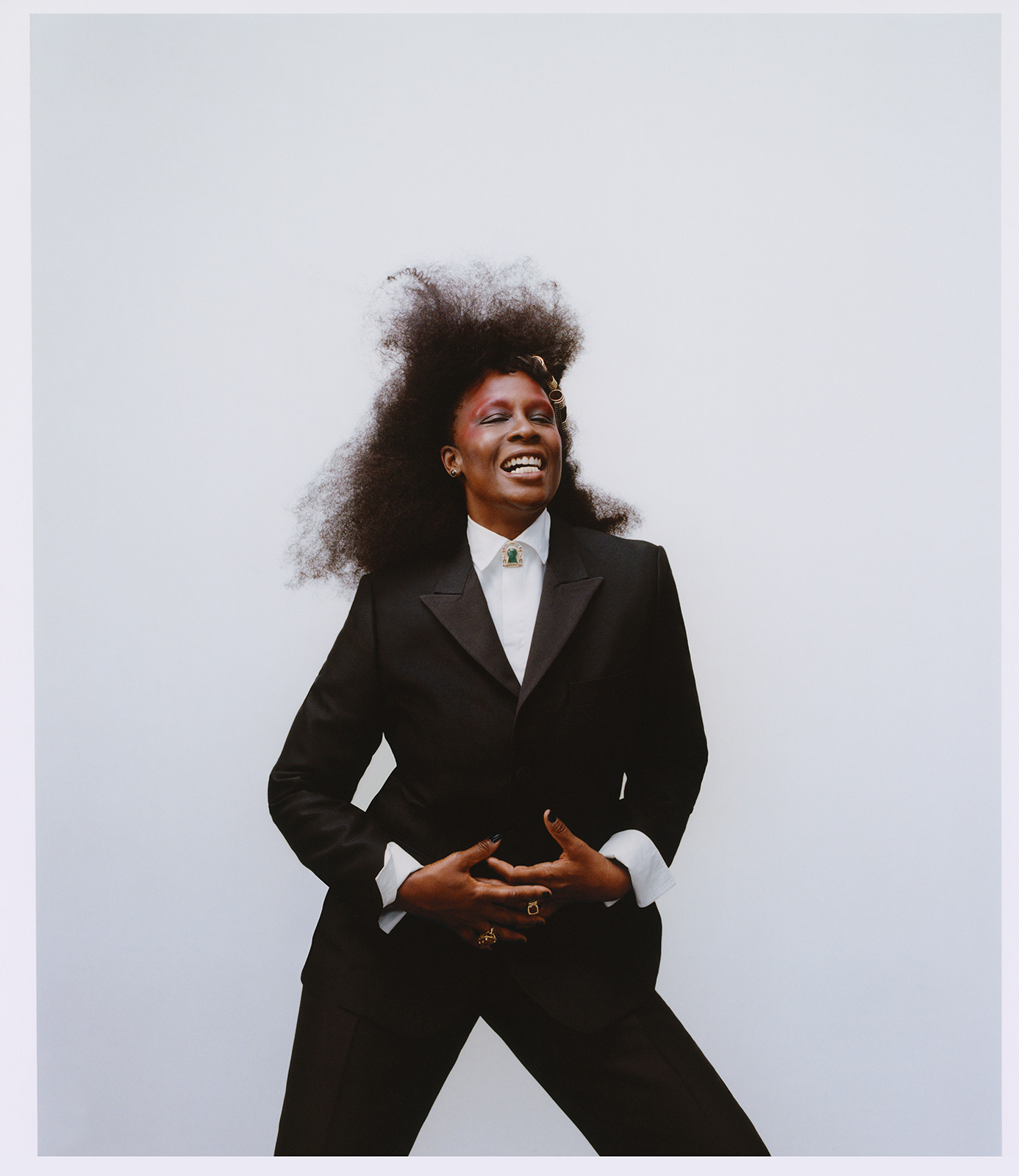

In the images accompanying this interview and on the magazine’s cover—shot by Joshua Woods and styled by Ronald Burton III with hair by Jawara—Thomas embodies her experience as someone intimately familiar with being both the artist and model. Just as Thomas and Waithe ask their collaborators to inhabit the characters they create, in her earliest lens-based works, Thomas cast herself as art historical tropes and other characters birthed from her imagination. That is to say, she’s played many roles for her own lens. However, for Document, she has transformed herself again.

Thomas’s performativity and brio in these photos reminds me of the early works she created while in graduate school at Yale in the early 2000s. The photographs were self-portraits where she posed as her alter ego Quanikah. The naïve, girlish beauty from two decades ago has become a glamorous model who understands dress as narrative, subject, and material. She still favors dramatic makeup and flamboyant hair, but now she rocks Christian Dior in all black. It’s not Mickalene, but it’s not not Mickalene.

For Document, Thomas and Waithe discuss how fashion informs what they make and what they wear, and what it means to be a dandy in a lineage of Black women from the Harlem Renaissance to the present day.

Monique Long: I spent a lot of time looking at images of your outfits—I’ve seen images at the Met Gala and all the award shows in LA, and both of you have these really refined styles. Lena, the tailoring and the suiting that you wear is very directional and committed.

Do you want to talk about how your style has evolved?

Lena Waithe: My style has evolved just as I have. I definitely think there’s a specificity in terms of being a queer Black woman who falls into the masc category where people say that we’re women in men’s clothes. Men don’t ‘own’ pants. They don’t ‘own’ suits.

I work with a ton of tailors because if I put a man’s suit on, it’s not necessarily going to hang on my body the way I want it to. I’m always hemming pants, pulling in the waist a little bit. So it feels like I’ve taken something that society has said belongs to one group, and I’ve transformed it and showed people that it belongs to anyone who wants to engage.

I do work with a stylist, Jason Bolden, who is fantastic. I’m a big believer in wearing brands by Black and brown people, sometimes queer people like me. Wearing L’Enchanteur has been so amazing, because when people come up to me and say, ‘I love these pants’—Mickalene did that when I was with her—I’m like, ‘The girls, Soull and Dynasty, did it. Two lesbians from Brooklyn totally made these.’ There’s a pride in wearing clothes by folks I actually know, by folks I get to support. Mickalene, you want to get into it? Because I know your style be killing them—the glasses, the hat.

Mickalene Thomas: Fashion is a way of impacting your environment and those around you. It allows you to make bold statements. I think of my body as a landscape or a raw canvas. How do I want people to perceive me as I navigate and move through multiple spaces?

My style is a hybrid of wearing luxury with clothing made by emerging and upcoming designers. You mentioned L’Enchanteur; when I wear their clothes, I feel like I’m connected to a sisterhood and community, an ecosystem and mission. That’s what fashion has the ability to do.

I remember when I purchased my first pair of Doc Martens, the big funny looking black steel-toes that were clunky and awkward. I have memories of being teased at school. I grew up in Camden [New Jersey] with my grandmother, and she used to work at a Salvation Army store, so a lot of my clothes were secondhand. I recognized and became self-aware of my style for the first time. I would always find ways of making them look really fashionable and add a quirky flare by altering the clothes.

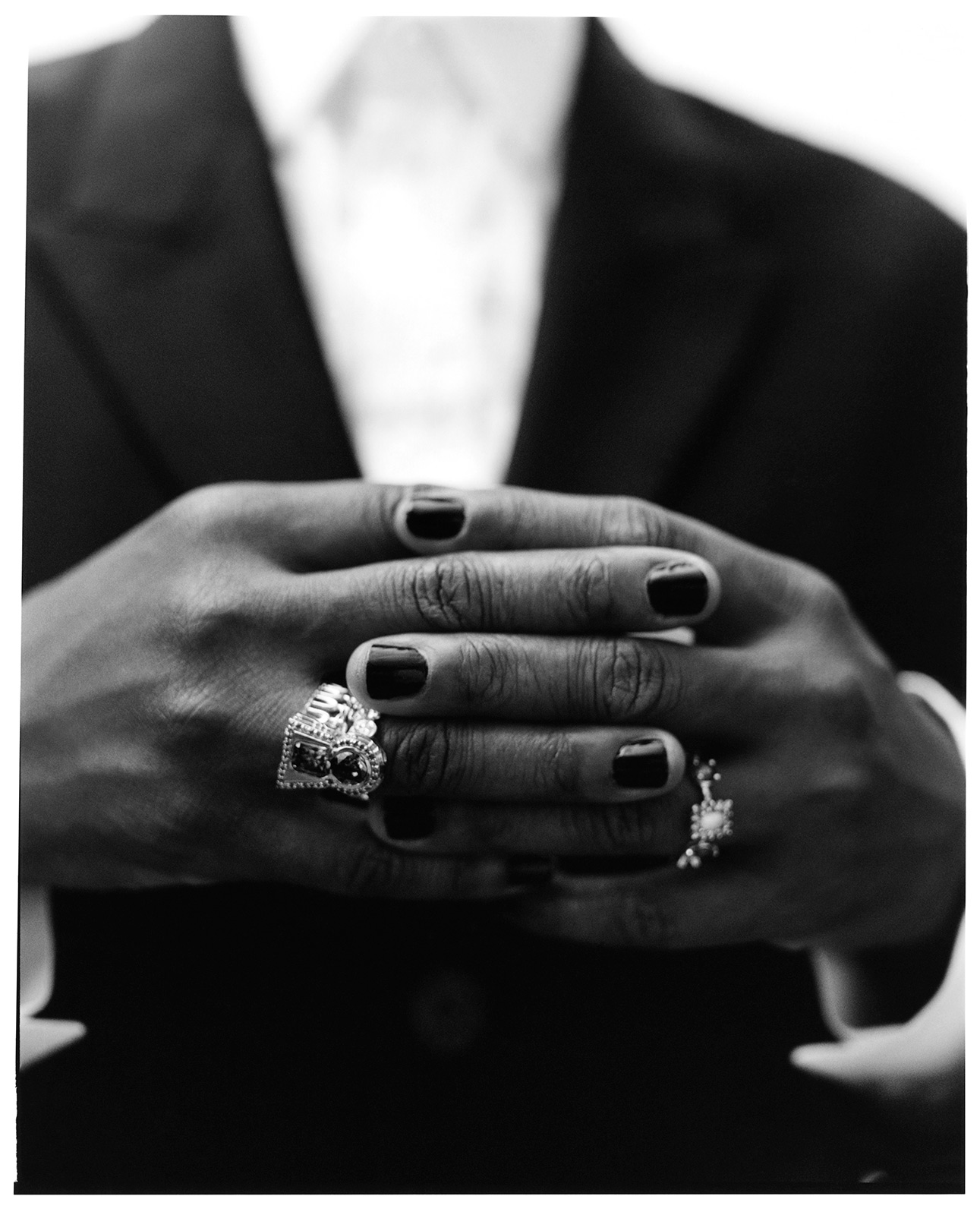

I’m a big believer in everything that you put on is an extension of who you are. That’s why I love accessories, I love my glasses, I love great jewelry from Mckenzie Liautaud, IPPOLITA, L’Enchanteur, and I love working with women, Black, and brown designers. I’m always supporting independent designers locally.

Monique: I wanted to talk about history, and figures like Josephine Baker, who wore her military uniform to the 1963 March on Washington. She was criticized for it, but it was a uniform that expressed pride. Or even Gladys Bentley, who wore suits back in the 1920s and ’30s in and around Harlem—not just in her performances, but in her personal life as well. I think, Mickalene, an outfit is a kind of collage. It’s something that you assemble and put on to express how you’re feeling, but you wear a lot of black every day.

Mickalene: I’m surrounded with so much color and pattern in my art that I feel like the black is a juxtaposition that balances out style and my life. And it is a uniform. If I like a pair of cargo pants, socks, or t-shirts, I buy multiple pairs or sets because I like the idea of uniformity and simplicity in wearing and creating my identity that is almost utilitarian.

Monique: I wanted to talk to both of you about costume as a narrative device. I see it in your painting. It’s a way to switch temporality. It’s a way to take you to that place of nostalgia. Lena, when you’re writing a character or developing a scene, do you think about what your characters are wearing?

Lena: I tend not to be specific about clothes for characters in a script, because I do want to leave space for the costume designer to come in and interpret.

I recently honored Shiona Turini at Harlem’s Fashion Row. She’s amazing. Her first costume design project was for Queen & Slim. And in that, I knew that when [my characters] went on the run after they leave Uncle Earl’s house, I was like, ‘I want them to look like they’re in a modern-day Blaxploitation film.’

Queen takes some clothes from some of the women that live with him. And what Shiona saw was like, ‘I’m going to do this snakeskin boot, the zebra print dress.’ She brought that. So yes, I knew that the only way I could show how they are going to be different at that point was through the clothes. It was like, ‘Okay, we’re different now. I’m wearing your Uncle Earl’s sweatsuit. You’re wearing a dress from a young lady who I don’t know how she makes a living, but we’re going to respect it. And we out here now,’ because it was my only way to show the audience that they’re on a different journey.

I’ve loved collaborating with really fantastic costume designers who pay attention to the words that are on the page and bring their artistry to it. And I’m grateful for all the work that they’ve done to illuminate the work that I’m trying to do.

Monique: I was fascinated by the choice of their outfits, the velour suit. It could have been the mid-’80s to the present. They were time travelers in a way. It instantly made Queen & Slim a classic because you couldn’t tell what year that it came out. Mickalene, I know you collaborate closely with the models that you cast for your paintings, but how do you work with them on the clothes?

Mickalene: When you’re first starting out, you work with your limitations, so you pull from your limited resources. I was basically pulling from the closets of my friends and family at first. Then, with a limited budget, I was going to Salvation Army and secondhand stores to look for clothing that reminded me of how my grandmother house dresses, styles that reminded me of how my mother and aunt used to dress. Also at that time, it was about draping the model with silky fabrics, because I was interested in how the fabric laid on their bodies with the patterns surrounding them.

As an artist, I believe that there’s a lot of performativity to portraying narrative and storytelling. I’m asking the viewer to believe in the storytelling of this image I’m putting out: ‘Believe this, believe this moment, believe this person’s sitting there.’ And if anything looks uncomfortable or awkward, you’re not going to believe the narrative.

So I always direct the models but ask for their feedback with the styles, have them look at the rack of clothes set out for the different scenes or portraits that I want to do, and try it on.

I want to provide a platform of comfortability where models can walk into the space and claim it: ‘This is so right. I own it.’ These environments remind them of their family houses. They’ll say, ‘I know this living room, I’ve been here.’

Monique: It was a lot of fun to think about a historicization of both of your personal styles through this lens of a Black woman who adapts the dandy figure. I’ve been thinking about it since Lena brought up this idea of subverting what is considered men’s fashion for her own body. When we say dandy, we always think of this male figure, but I think of both of you very much as dandies, where style is a part of your practice as artists.

Lena: I love that word. And I think someone would definitely put Colman Domingo in that category.

Monique: I love him, yeah.

Lena: He and I are friends. I mean, that’s not a secret. But I think if you put myself, Mickalene, and Colman at a table, we’re all going to be speaking the same language. Because when we think about dandies, we often think of queer men or men who are not afraid to be flamboyant, but also lean more in the masc space too. It’s a very interesting space, and I think for Mickalene and myself, the spaces that we occupy and rooms that we’re in, we’re able to float and adapt. But it’s not code-switching. It’s more so that the room has to adapt to us versus the other way around. And I think ‘dandy’ is a very appropriate word in that case.

Mickalene: I love that word too. It’s just so rich, right?

Lena: We don’t use it enough.

Mickalene: It’s unapologetic. And it’s sophisticated, it’s elegant, it’s strong.

Monique: And it doesn’t need to be gendered. I don’t think there has to be the female version of a dandy.

Mickalene: There’s a softness to the flow of it when you see it. It’s hybrid, this weird combination of all that stuff in the middle. You can close your eyes and imagine the walk. The posture, the confidence.

Think of someone historically too, like Pauli Murray. All of these queer women before us who claimed that space proudly. When I came out, my first suit that I had was this vintage three-piece, striped double-breasted suit. And I kept that thing clean. It was my suit. I got it from the Salvation Army in Portland, Oregon, when I lived there.

Lena: Oh wow.

Mickalene: I remember wearing the suit to a Carrie Mae Weems opening on October 31st, 1995. She was having an opening at MoMA’s project space. The exhibition was photographs, I think, from one of her trips in Africa. It was my first time meeting her, and I met Okwui Enwezor there the same night.

Monique: Wow. Another dandy.

Mickalene: Another dandy, exactly. I remember distinctly, I felt like he validated my fashion that night. I’m there, nervous, anxious, so many art world folks and Okwui singled me out and came up to me. I’m there with my mentor, Rahimah Lateef, she wanted me to meet Carrie Mae Weems. And I’m at my best, I’m looking good in my three-piece pinstripe Goodwill suit. Okwui Enwezor comes up to me and goes, ‘Where are you from?’ I said, ‘Oh, I go to Pratt but I just moved from Portland.’ He goes, ‘Oh, I thought you were English.’ He’s like, ‘You look sharp. You look good.’

Monique: Money well spent.

Mickalene: That suit got me in some doors.

Monique Long is a writer and curator based in New York. Her current exhibition, When the Children Come Home, is on view at the Sugar Hill Museum of Art in Harlem through February 2025

Talent Mickalene Thomas. Hair Jawara at Art Partner using Oribe. Make-up Yumi Lee at Streeters using Dior Beauty. Set Design Alice Martinelli at CLM. Manicure Pika at See Management using Essie. Photo Assistant Shen Williams-Cohen. Stylist Assistant Jody Bain. Tailor Kerry Phelan. Hair Assistant Roddi Walters. Make-up Assistant Yuka Ito. Set Design Assistant Kaeten Bonli. Producers Devon Welstead and Mary Goughnour at CLM. Junior Producer Caroline Westdyk at CLM. Production Director Lisa Olsson Hjerpe at CHAPEL Productions. Post Production Ink Studio. Shot at Laobra.