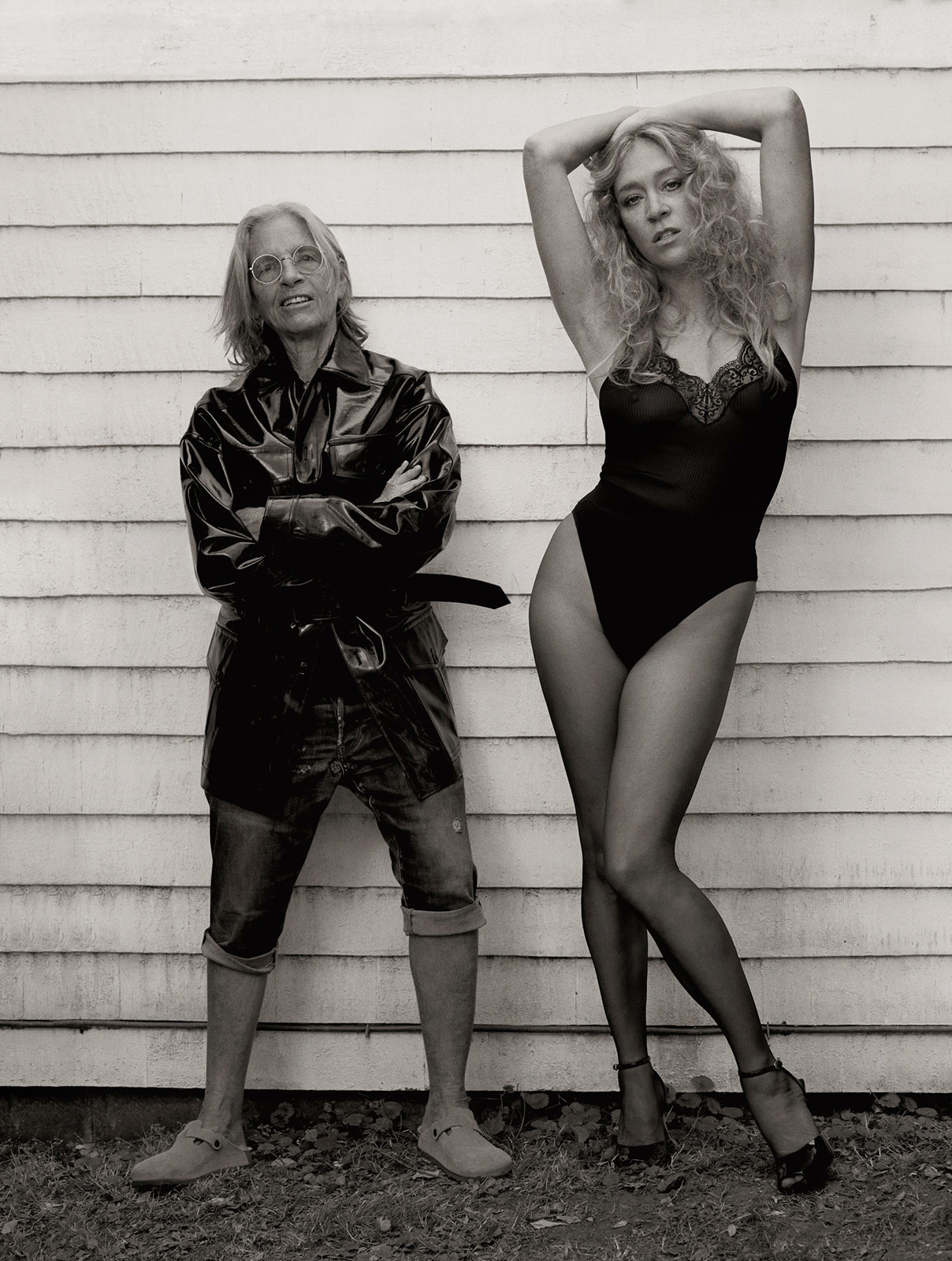

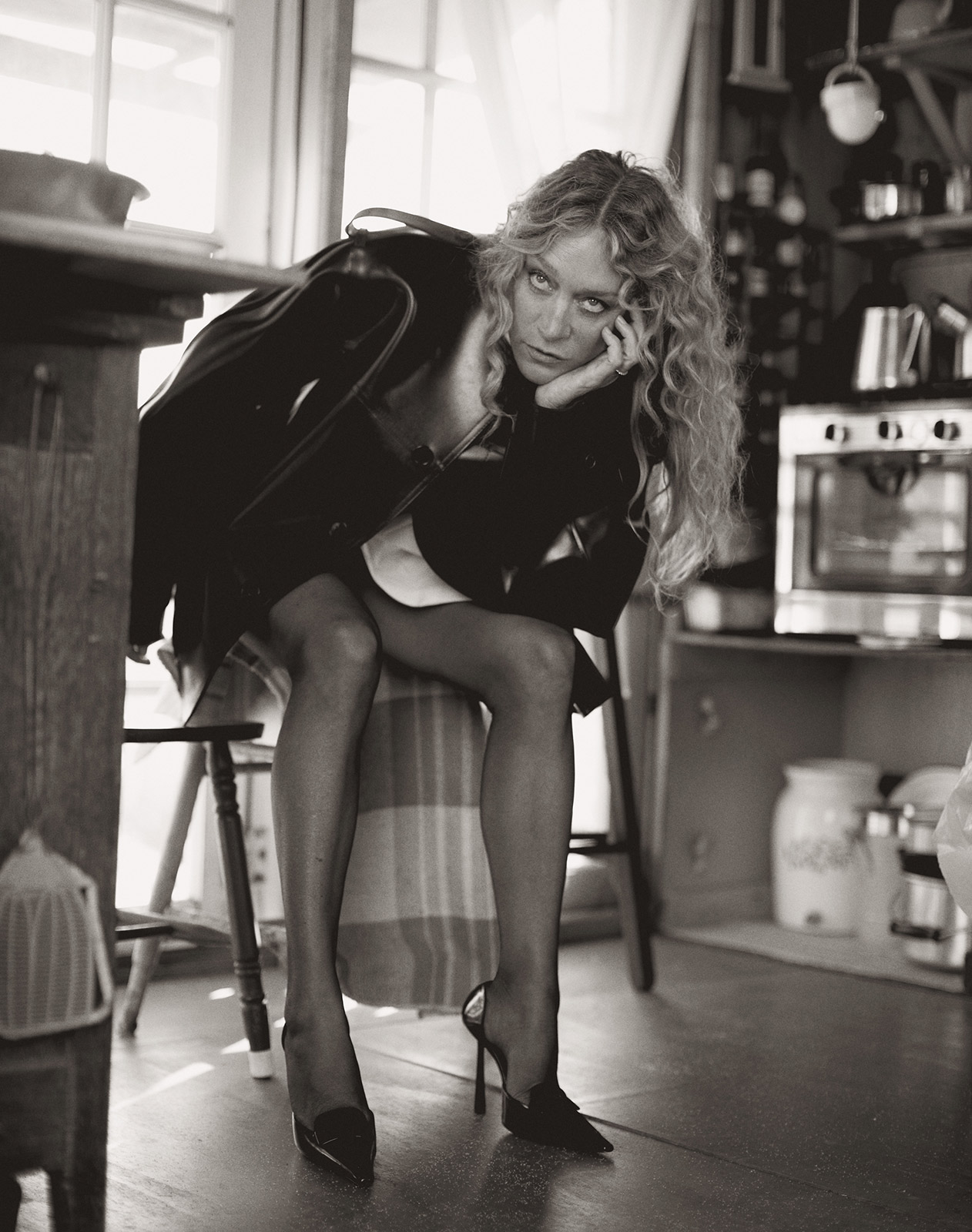

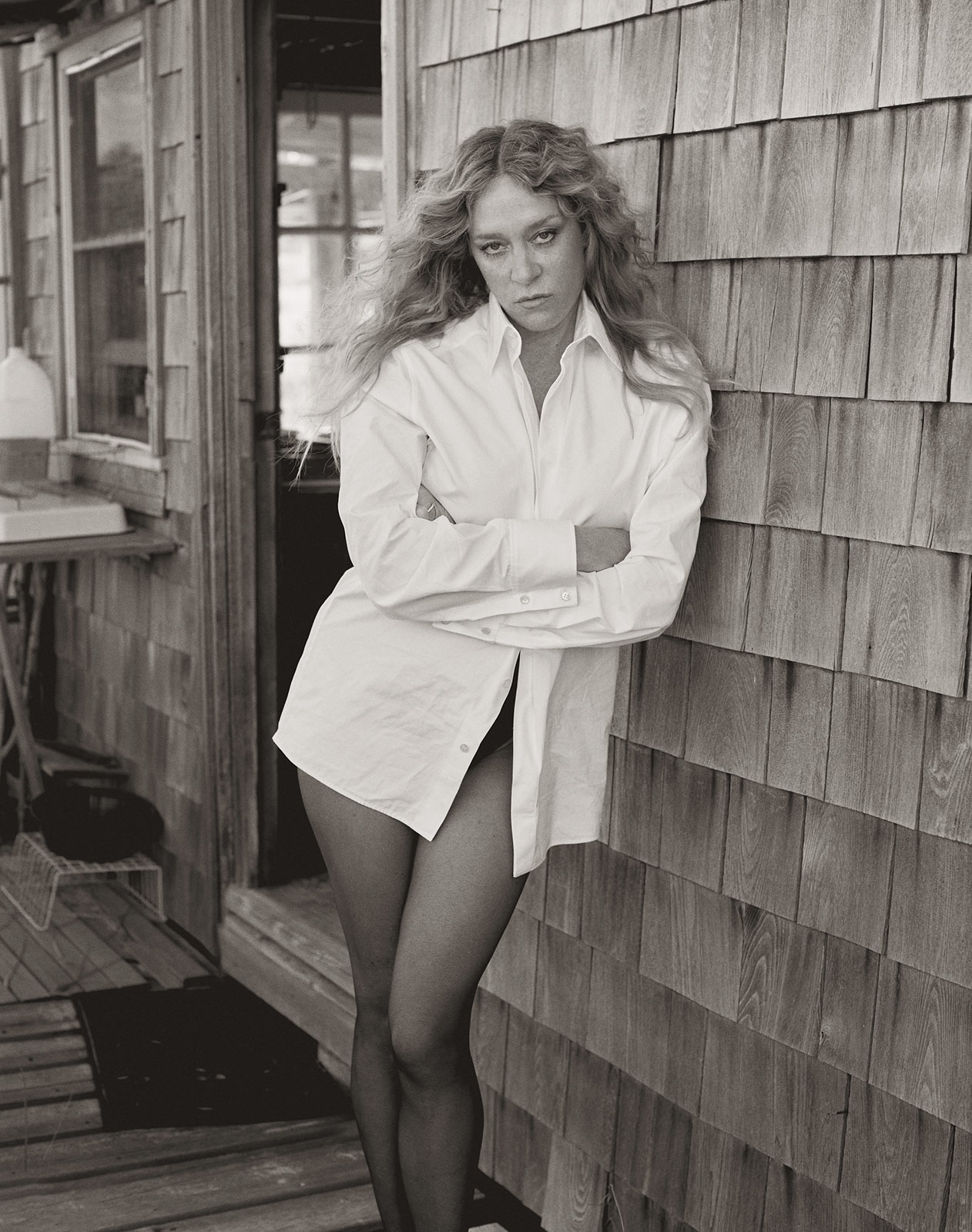

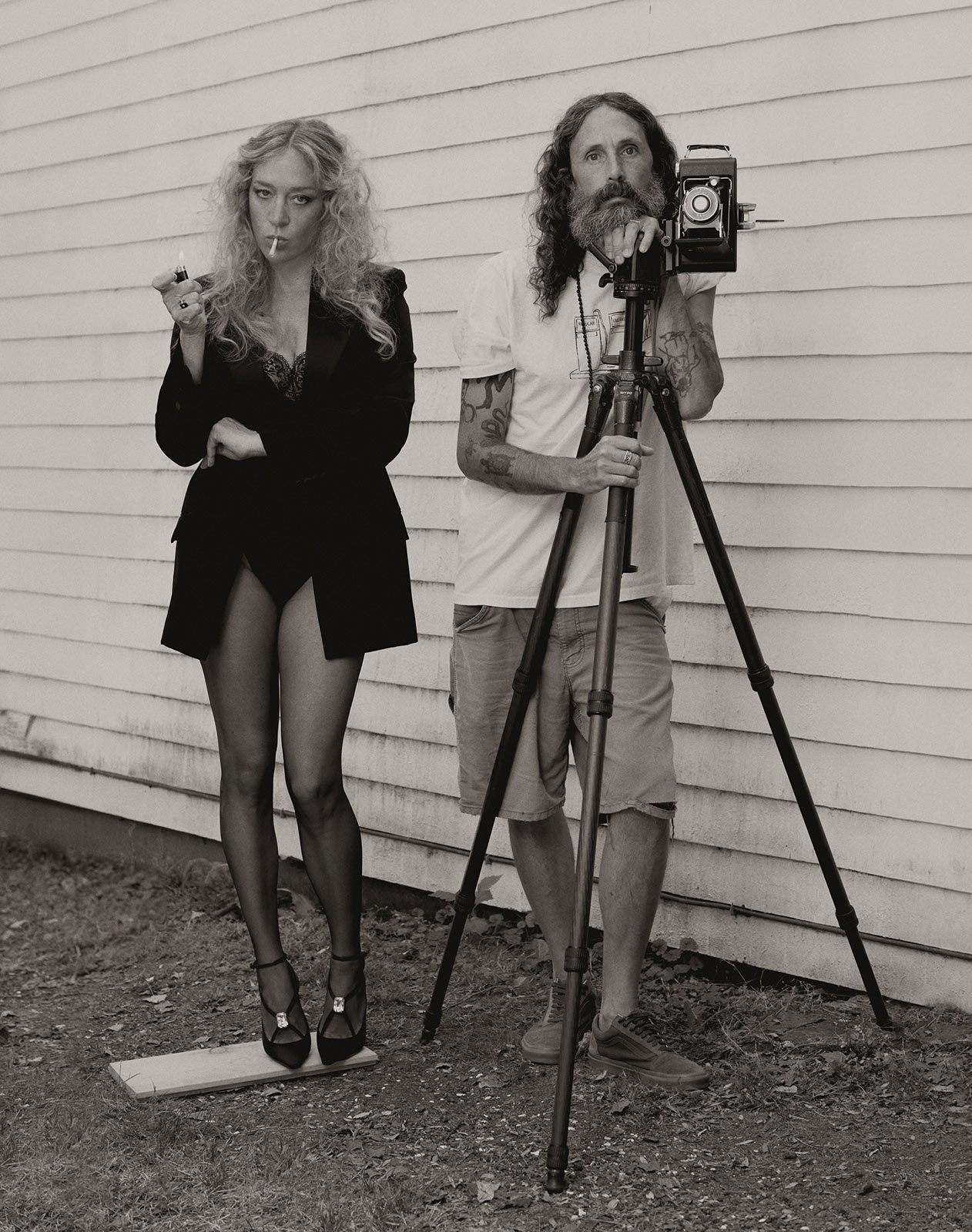

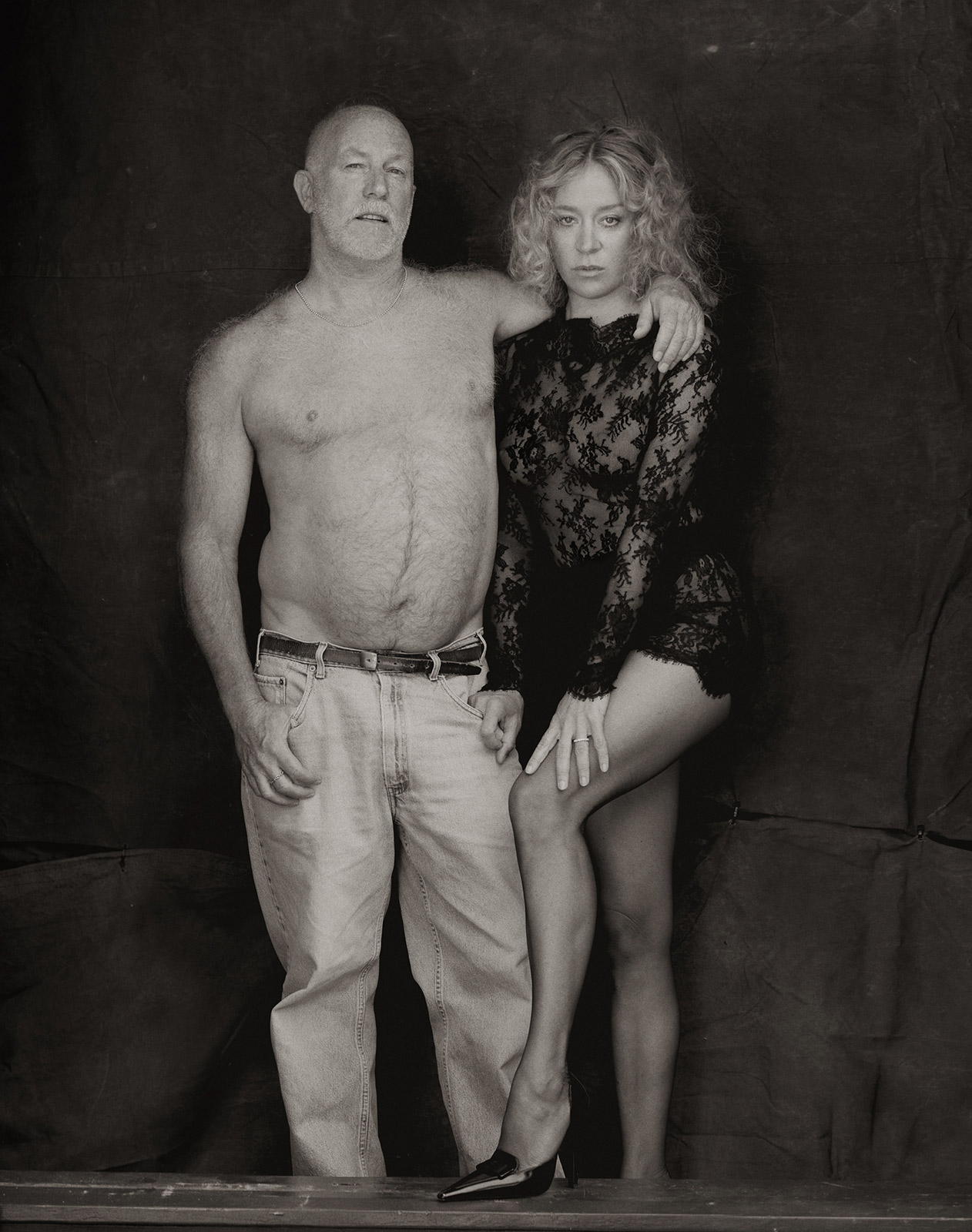

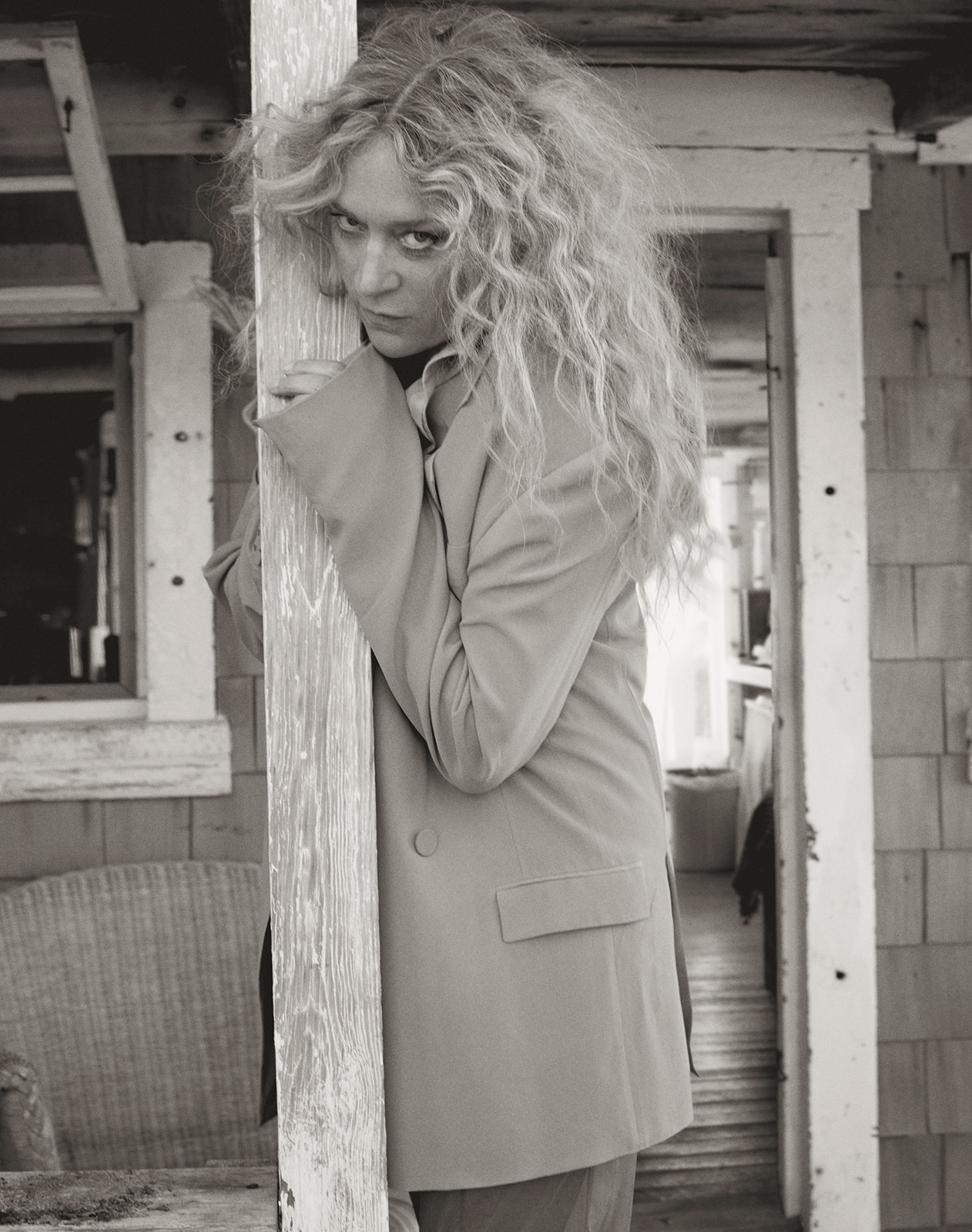

The filmmaker and actor joins the writer to talk about performance, Provincetown, and loving the broken and pathetic for Document’s Fall/Winter 2024–25 issue

There are indie icons or mainstream luminaries. Local legends or international sensations. Those who remain underground or those who embrace visibility. Then there’s Chloë Sevigny. The critically acclaimed actor and filmmaker has spent a career blurring these, and many other, boundaries. As much as Sevigny is undeniably a “celebrity,” she’s remained tethered to the downtown environs she came up in since she first appeared in Sonic Youth’s “Sugar Kane” video back in 1993. She has received enduring critical recognition for her acting in cult-classic films like Kids (1995), Boys Don’t Cry (1999, earning her an Academy Award nomination), and Demonlover (2002), while enjoying mainstream success for her roles in series like Big Love (2006–11) and, recently, as a muse to television impresario’s Ryan Murphy in two miniseries. Sure, she also designed capsule collections, but for friends like Opening Ceremony—not for megacorporations. And you might be among those who got the chance to purchase her personal vintage fashion finds back in May 2023, when she hosted a public closet sale so coveted it generated its own news cycle.

What distinguishes Sevigny—what renders her boundary-bending possible—is the honesty she brings to all her work. The authenticity of her generation-eliding prestige rang clear when she strutted as the preeminent it girl to rule all it girls—alongside zillennial favorites like Julia Fox, Alex Consani, and Hari Nef—in Charli XCX’s “360” music video. She is, in the words of Eileen Myles, “our actor.”

An award-winning poet, novelist, activist, and 1992 presidential candidate, Myles is among the most influential figures of contemporary English-language literature. Their genre-spanning body of work, published since 1978 and numbering in the double digits, includes the poetry collections Not Me and Sorry, Tree, the novels Chelsea Girls and Inferno, and the non-fiction books The Importance of Being Iceland and Afterglow (a dog memoir). In 2023, they edited a nearly 700-page volume called Pathetic Literature, which resuscitates the pathetic as a queer and feminist modality in writing bridging millennia. Throughout their career, they’ve also used their platform to advance causes dear to them, including a major effort to protect the East River Park from ongoing demolition by the city.

The poet Cedar Sigo writes that Myles “does well to recognize that the public is more interested in poets than in poetry.” Something rings true in this quote for Sevigny too, who, despite her tremendous acting and directorial career, often gets an outsized reputation for her iconicity in fashion and in successive Lower Manhattan scenes.

Longtime New Yorkers, Sevigny grew up in Connecticut; Myles in Massachusetts. Sevigny and Myles were shot for the cover of this magazine together in Provincetown, the artistic and queer haven at the tip of Cape Cod that both of them have been returning to year after year. Provincetown isn’t somewhere Sevigny or Myles go to discard the world but to become closer to another possible one. In their essay “The End of New England,” Myles quotes Thoreau on Provincetown as writing “here a man can stand and put all of America behind him.” To that they ask: “Can we?” I take this question, in part, to mean that the work of an artist refuses to neglect the histories and presents that live through their speech and body and the humans and beings of all kinds around them. The creative practices of both Sevigny and Myles reach toward those who know that art should make life weirder, freer, and simply more interesting.

“I don’t think I wanted to be famous, I think I wanted to play make-believe.”

Eileen Myles: How was it coming back from P-town for you? How was your experience?

Chloë Sevigny: Well, it was full-tilt boogie. I had to go to Toronto for this Bonjour Tristesse movie that I’m in that Durga Chew-Bose wrote and directed. So I came home, had all these fittings, got into the frame of mind of even doing this interview. I had to re-enter into that mode of having to articulate my work.

Eileen: Right, right.

Chloë: One of the more challenging aspects I find as an actor is I always feel like it’s Durga’s movie, it’s her expression. I’m acting in it, and I’m doing an expression of my own, but she adapted it. It’s the story that she wants to tell, and she ultimately has the control. I still am kind of at a loss as to how to really talk about a movie that I haven’t made myself. I can talk about my experience on it, how I try to infuse myself into the character, but the overall gesture is hers, or theirs, or whoever makes it.

Eileen: It’s almost masochistic in a way. I understand masochism not so much as ‘hurt me’ as ‘What’s going on here? What can I have? What’s the situation? What shape do you want me to be in it?’ The masochist conforms. You say yes to a movie; there must be something about that setup that you like.

Actors totally fascinate me. When I think about being an actor as your art form, you’re fucking turning into somebody different all the time. Or is that not true? The loss of identity. The little bit of acting I did scared me.

Chloë: It varies so much. When I did, for instance, long-form television, like Big Love for HBO, I played this character, Nicki Grant, who was very complex, and more was revealed about her as every season went on. There was one season where everybody was accusing her of cheating and being a bad person, for lack of a better way of articulating it. I would really internalize it, and that season was very hard for me to do. But I could do a movie, and I’m in five scenes, and everybody thinks I’m a bitch in the movie. I think it depends on how much time you’re in that person.

Eileen: Who are you in Bonjour Tristesse?

Chloë: I am the older woman that gets scorned and drives off and kills herself because the man that she loved left her for the hotter, younger woman.

Eileen: Holy shit.

Chloë: Which I really bumped up against. I was like, ‘I don’t know if I want to keep perpetuating that.’ I mean, especially that she drives off and kills herself. But I think that my character infuses the drama, and I do know a lot of women whose men leave them for someone younger. You’re perpetuating it, but it’s a truism.

Eileen: You’ve had this whole long career, and you’ve been an actor since you were a teenager, and so you’ve been all kinds of women. The only reason I know it’s fashion week is because of you. You continue to be out there as the hot woman who everybody wants to put their clothes on, and yet it seems like the cliché of Hollywood when you move into TV shows, you’re somebody’s mom. What’s that like?

Chloë: In Bonjour Tristesse, I’m quite glamorous, I have to say. She’s an artist, she’s a fashion designer, she’s somebody that grew up in New York. I was trying to draw on people that I know. And she talks a lot about her art, which I always find really strange to articulate on the screen. There are very few representations of artists in the movies that aren’t just…

Eileen: Really stupid.

Chloë: Really stupid. Wait, what did you act in?

Eileen: In my moment of dating Joey Soloway, I was in Transparent. And I still suffer because I feel like I didn’t act well. I mean, I had been in friends’ independent films. I actually always thought, Oh, I look good. ’Cause I hate having my picture taken. I feel like I’m really bad at being still. So when I’m moving, I feel like that’s what I think I look like. I enjoyed it, but I didn’t know when you moved to the big time and you’re in a scene and you’re sitting on a bed talking to somebody and there are all these cameras coming toward you, you didn’t have to be loud. Nobody told me.

Chloë: What about when you’re on stage reading? I guess that’s not really acting…

Eileen: But it is performing, and I know who that person is. I can get on stage, and it’s the most normal thing in the world for me. I’m very comfortable in front of an audience.

Chloë: But you have to lean into people’s expectations. Say you’re in a bad mood, do you have to adjust?

Eileen: One thing I know about live performance is that you have to not be afraid to notice what you’re actually thinking about, and then use that.

Chloë: To take the time.

Eileen: Not to take the time, just be in the time. Like, get off the script right away, and be in the room—because people can feel it.

You started acting as a teenager or a child, why did that happen?

Chloë: I did it as a child unprofessionally, but my first real professional gig, I was 19.

Eileen: Did you have a stage mama, or did you want that?

Chloë: I wanted that.

Eileen: Okay, so you wanted that, why? Just ’cause who wouldn’t want to be a famous actor?

Chloë: I don’t think I wanted to be famous, I think I wanted to play make-believe. I saw Annie on Broadway. And then I saw, obviously, Little House on the Prairie, which I cite all the time. I was obsessed with colonial times. There were different places we would go visit, like Mystic Seaport. And all throughout Connecticut, there were the schoolhouses from 17-whatever. My mom was from Philly, and we’d go to Betsy Ross’s house and Independence Hall. I was like, I want to live in a different time.

Eileen: It’s so interesting that some kids want to go into the future, and some kids want to go into the past. Did you ever get woo-woo about it, like with reincarnation or that you actually did live [in the past]?

Chloë: I do now. I do think I have some past lives. I was brought up Catholic, and I was very into the church, and so I was always thinking about heaven growing up. But now I do think there are certain people in my life that I know we have some unsettled scores. Do you have that?

Eileen: I’ve met people who I know I just piss off. I used to get it a lot when I was younger from men. I would be with my gang of girlfriends. Later I thought, Oh, it’s because I’m a dyke. It was just ’cause I was talkative among my gang, and they thought girls were supposed to be quiet. Like, ‘Who the fuck is this one?’

Chloë: You’re a disrupter.

Eileen: A little bit.

Chloë: Are you still writing movie-ish stuff? I remember when we first started meeting and hanging out, you had that incredible pilot that I still think about, and think should be made somehow.

Eileen: No, I’m a little bit on a departure, because I’m working on this giant-ass novel, and I think I’ve got another year to go on it.

There’s a thing about Chelsea Girls, too, which people keep coming to me and saying, ‘Let’s do it.’ The film world is very confusing. It’s very bipolar.

Chloë: It can be a lot of enthusiasm for a minute, and then it just halts.

Eileen: I find that hard. I guess any human being would find that hard.

Chloë: And what’s the big novel?

Eileen: It’s called All My Loves. The idea is that it’s 1,000 pages. I was breaking up with somebody and I felt like I wasn’t just breaking up with her, I was breaking up with everybody. I was having all these flashbacks of little bits and pieces of people I had lived with.

Chloë: Every breakup kind of does that, right? You do an inventory of all the loves lost.

Eileen: And you still do things that they made you do. Like dog food: if you feed the dog, you’ve got to wash the spoon right away, you can’t put it in the sink. That’s a rule. Certain things like that, I still do in honor of that girlfriend. Did you see the moment where everybody was reading Knausgård, the Norwegian writer? He wrote a book called My Struggle. He used Hitler’s title, and it was seven volumes of male genius, every detail about his dick. It was just incredible. I never read it, ’cause I was like, ‘Fuck him.’ But it’s so big that at some point I thought, I want to write a work of male genius. So I decided to make the book be big. I started to think if it’s about love, it can be love of dogs, love of Provincetown. I’m expanding it. It’s big, and it’s going to be weird, because big books are like big movies—nobody wants to spend that kind of money. It’s a nightmare for publishers. They like Bonjour Tristesse, they like a 100-page book. And I do too, I love a 100-page book. That’s not what I’m doing, I might be writing 10 100-page books.

Chloë: Make them all little slim volumes.

“I grew up being very into the independent an anti-culture. It was a real badge of honor to be a part of that.”

Eileen: Yeah, that would be nice. Did you see Civil War?

Chloë: Civil War? No. Is it a movie?

Eileen: It came out recently, and it was sort of dystopian.

Chloë: Oh, right, with Kirsten Dunst. No, I did not see it. I would like to. I have a four-year-old, I haven’t seen anything. I haven’t read anything except Berenstain Bears. I am so far behind on everything. Whereas before I had ample time and now I don’t. I need to get into some sort of practice, even just reading and watching, and writing or doing whatever.

Eileen: Everybody I know who’s an artist who has kids has said that. Friends who were painters said that they used to go into the studio and hang out, read a little bit, listen to some music and do all this warm-up shit, and now it’s like, ‘Go into the studio, you have two hours because your partner has the kid now.’

Chloë: I used to read at work, or go in my trailer and watch and read stuff, and now I’m just like, I’m working on my lines or working on work at work so I don’t have to do it when I get home.

Eileen: I feel like, in a deep way, I would just be happy on the couch all day long, reading. That’s what I really, really love to do. Even when I’m working, I take hours to start work.

Chloë: But I feel like you’re very productive. You’re always publishing stuff, you’re always having readings, you’re always out being active.

Eileen: I’m very active, but the life generates it. My email is filled with, ‘Will you blurb this book? Will you do a reading tomorrow?’ Last night, Nicole Eisenman had a book launch. It was really fun, it was really good. The writing was great. It was all these writers that were writing about her work. It was kind of great for me because I’m not in the book. It was cool to go to an event that I had nothing to do with.

Chloë: That’s very relaxing.

Eileen: And that’s what I don’t do enough of in New York, because I’m continually doing the performance of being me.

Chloë: I’m so smitten with her.

Eileen: Nicole?

Chloë: Yeah.

Eileen: She’s the greatest. I have a great painting of hers over…[Eileen lifts their computer to show a painting on their wall to Chloë] It’s a pack of cigarettes slash a can of pepper.

Chloë: Marlboro Black Pepper. That’s nice. Lucky.

Eileen: When I first met her in the ’90s, she read my poetry, and by that time I didn’t smoke anymore, I had just gotten sober, but the book was full of drinks and cigarettes, and so she just did this drawing for me that was cigarettes and a pepper can. I know she’s wanted it back. She was like, ‘Maybe I could borrow that piece and give you something else.’ I was like, ‘No. No.’ She’s kind of my favorite artist.

Chloë: When I was first introduced to her, I was in Pittsburgh making a show. The Carnegie International was on, and she had all of these big figures throughout, those white figures with the dried flowers, and paintings sprinkled throughout the museum, and you had to go on the scavenger hunt to find them. I was obsessed with the humor, and I fell in love. I didn’t meet them until last summer.

Eileen: They just started to be P-town people.

I mean, they have the thing where they just make work, and make work, and make work. I feel like they had a good childhood. One of her first shows there was a big mural, but then there was a wall and it was all this little shit. And the funniest part of it was there was a drawing like, ‘Pablo Picasso, age nine.’ And then there was a drawing by her: ‘Nicole Eisenman, age six.’ She’s been written about in the Times, and they interview her mother, and she was like, ‘I always knew she was a genius.’

Chloë: Wow.

Eileen: You always read about men like that, and it’s amazing that there’s this woman, and that she just…

Chloë: Do you think women are more damaged by their mothers, maybe?

Eileen: Hell yeah.

Chloë: Sorry, Mom.

Eileen: Can we talk about your mother, or my mother, or neither mother? I don’t know. I think mothers look at their daughters and feel jealous. If you’re going to college and she didn’t. If you’re going to Europe, if you have a career, it’s just like, ‘Grrr.’

Chloë: It’s very complicated. I feel lucky for Vanja that he’s not a girl, ’cause I feel like it would be very hard for me to break the cycle.

Eileen: That’s an amazing thing to say.

Chloë: I can admit it. Even with my girlfriends, I’m like, ‘Maybe you should wash your hair. You would look so much prettier with clean hair.’

Eileen: Wow. Wow.

Chloë: I’m just like my mom, you can’t shake it.

Eileen: That’s incredible. Usually everybody I know who’s having a kid, they were like, ‘I want a girl. I don’t want a boy.’

Chloë: I wanted a girl, but now I’m lucky I have a boy. I feel like he’s lucky.

Drew Zeiba: I was recently rereading the intro to the Pathetic Literature anthology, where you, Eileen, take the pathetic as what you call a ‘badge of distinction,’ especially in writing and work by women and queers, and you have this moment where you say you’ve collected these writers for ‘their dedication to a moment that bends not in a gay way, but you know how when you’re walking toward a horizon it seemingly dips. And you feel something. That’s pathetic. It’s an empathetic thing… People get different.’ And Chloë, I got to see Lypsinka: Toxic Femininity—your film highlighting John Epperson’s tragicomic drag persona who lip-syncs to spliced recordings of different, ill-fated Old Hollywood grand dames—at the premiere, and I was thinking about this sort of frame, this re-invocation of pathos. I was curious about, for both of you, the emotional or affective dimensions that you’re interested in, whether it’s in your writing and editing, Eileen, or in your acting or your directorial work, Chloë.

Chloë: With Lypsinka, that was all John. He had been given the task to make a piece of art during Covid about resurrecting this character. When I heard the audio, and I found it so emotional, I was very excited to spend my time developing that and seeing it through, because I think the female struggle, through his eyes, is very explored. Also being a performer is very explored in that piece.

Eileen: But I feel like the kinds of roles you take, the kind of woman you are—you’re very into the pathetic. You don’t do the standard beauty. If she is that, something bad happens to her in a weird way, or there’s always an oddity. There’s an offness to however you pitch yourself, it seems to me. I think that’s why lots of us feel like you’re our actor.

Chloë: Well, that’s just how I grew up. Sitting alone in school at lunch, being alternative, or punk, or whatever it was. Then being very into the independent and the anti-culture culture that was so prevalent, especially in the ’90s when I was growing up. It was a real badge of honor to be a part of that. Now that kind of underground doesn’t even really exist anymore.

Eileen: I think that’s kind of why I did that book in a way, because I thought what was skewed and off and pathetic used to be just what was… That was what we liked. I still love New York, but I loved it because it was a wreck. We were just camping out in a broken city, and there was lots of room for us, and you could do anything. And it was really running away from home for the first time, and finding yourself in a world with a lot of oddity. I expected things to be scarred, and written on, and funky, and oddly shaped. The vision of beauty was just an offness.

[The Poetry Project at] St. Mark’s Church was where I hung out, and it seemed related to music, and painting. It wasn’t academic poetry—it was more this poetry in the world with all the other artists. We thought we were the center. We were what mattered. Slowly, we’ve started to become ‘experimental’ and ‘fringe.’ Even the word ‘bohemian’—nobody ever used that word. It would’ve been really gross, and now it gets thrown around all the time. [With Pathetic Literature] I wanted to make a big, fat volume that pulled together this kind of emo nature from all time, and say that there were representations of it from 1,000 years ago. Somebody that was just making a sad list. Bad love, all of it.

Have we talked? We’ve talked…

Drew: You’ve talked. Thank you so much, both of you.

Eileen: I think that was good. It was good to see you, Chloë.

Chloë: Yes. See you around, I hope.

Hair Dennis Lanni using Hairstory NYC. Make-up Rie Omoto at See Management using Dries Van Noten. Digital Technician Thomas W. Photo Assistant Ethan Greenfield. Stylist Assistant Claudia Chick. Tailor Frances Gootman. Production Director Lisa Olsson Hjerpe at CHAPEL Productions. Associate Producer Colin Boyle. Production Assistant Kyle Amerantes at Milk Studios. Casting Director Anita Bitton at Establishment New York. Special thanks to The Town of Provincetown, Mary DeAngelis and Ryan McMenamy.