The pair sit down with Document to discuss the memory work in Okoyomon’s new poetry collection, ‘But Did You Die?’

On the eve of their 31st birthday, Precious Okoyomon is headed to Fire Island. “We saw shooting stars on my last birthday,” the Nigerian-American poet and artist tells me on the phone, “which was incredible.” This year, there’s supposed to be a meteor shower.

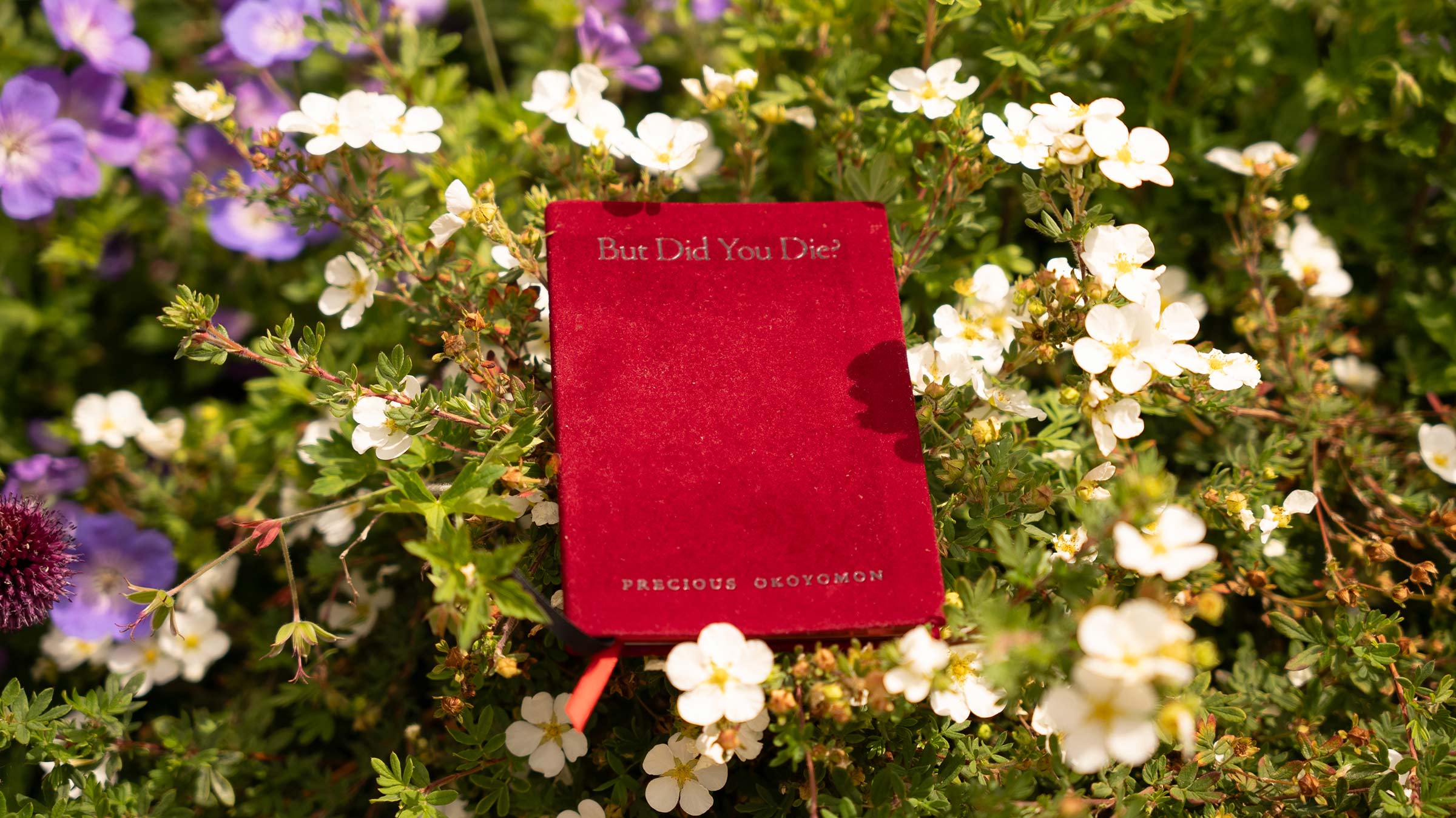

It’s fitting that Okoyomon would find themself looking at the sky at a time of such change. Their new book of poems But Did you Die? was just released earlier this month through Serpentine Gallery and Wonder Press. It is a masterpiece of self-transformation told through bright drawings and deliciously unrestrained poetry. Bound in soft red velvet and printed on bible paper, But Did You Die? speaks to the chaos and the specialness of becoming. As such, it’s been many years in the making.

Though Okoyomon began their career as a poet, they have a broad body of work as an installation and performance artist. After shows at London’s ICA and Zurich’s LUMA Foundation, Okoyomon worked on a wide range of projects about community, such as culinary art project Spiral Theory Test Kitchen (“my favorite practice being food making,” Okoyomon says), and Cloud Chronicles at Foundation Beyeler in Basel. In this new poetry collection, they bring the ecstatic moods of their installation and performance work brilliantly onto the page.

Caribbean video artist, computer programmer, and archivist Olivia McKayla Ross is no stranger to the ecstatic. Alongside director Jazmin Jones, Ross works through historical archives and the personal somatic process of memory-making in feature documentary Seeking Mavis Beacon, a film centered on investigating the disappearance and reexamining the legacy of the titular character, one of the most influential Black women in technology.

Olivia considers herself a “memory artist,” a self-description that reflects her practice of studying time as it extends past the archival and into the poetic. Okoyomon is a scholar of ‘Pataphysics, a science of imagination. As the pair sits down with Document, they talk about memory work, friends and inspirations, lost histories, and how But Did You Die? is both book and time-machine.

Olivia McKayla Ross: Where are you on your journey? Are you rolling through the hills now?

Precious Okoyomon: I’m basically almost there. I’m at the end of my journey.

Zoey Greenwald: That’s so exciting. I hope that you see many deer.

Precious: A few years ago I saw dolphins! I saw a whale!

Olivia: I love that we’re really big on whales.

Precious: Have you read Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s book Undrowned?

Olivia: I’ve read potentially everything Alexis Pauline Gumbs has published.

Precious: Amen to that. What an icon. I’m an M Archive fan, as an end-of-the-world archivist. That book was so transformational.

Olivia: Who or what have been the other biggest influences on the kind of meaning-maker you’ve become today?

Precious: It’s a lot of thinkers honestly. Simone Weil. I discovered her work very young, and it had a huge impact on how I view spirit, and grace. Bracha Ettinger is somebody that’s really big for me: an amazing psychoanalyst and, like, world-weaver. I think I had a community of love. I had a lot of people show me grace and then it taught me about how you hold other people. Like Ben Fama inviting me to do a reading. Dana Ward being my friend when I was very young, showing me things, helping me with my poems, doing readings in his house. Anne Boyer is somebody I love a lot and like I find that it’s really just been a blessing. I’m lucky.

Zoey: Oh, I wanted to know if either of you have current poet crushes.

Olivia: [Laughs] Precious, when we first met, Zoey and I were doing a reading and the theme for the reading was that everyone had to invite their crush. I didn’t have a romantic crush at the time, but you were my poetry crush.

Precious: Aw! Yes, I have so many poetry crushes! Forever, my heart is crushing. I have such a crush on Alice Notley. It’s crazy. I went to her house and I cooked for her. I had her in the show I did at Basel and I was like, ‘Come to the Beyeler and do whatever you want. I just want to give you money to be yourself. She read her poems every hour and then, like, wandered in the field. She’s such a vibe. She’s dreaming in and out of worlds co-consciously. Spell maker. Time traveler. Forever crush. And there’s this poet Fredrique Mayröcker. Fredrique Mayröcker is a freak. The poetry is so beautiful and the little books are really lovely. It’s drawings and poems, and the way that the rhythm of them reads… It literally is a spell.

Olivia: But Did you Die? is also full of really lovely illustrations. There’s a page of pure yellow, which touched me emotionally in a way I couldn’t quite place.

Precious: It’s funny, because the book is actually a lot about colors. Colors often symbolize places in my life, and that time was yellow with a slight green, a tinge of bright red through it. So in the book, the yellow comes up like, ‘I’m feeling yellow again,’ and sometimes there are no words and it’s just yellow. Because sometimes there were no words. The very design of the book is the poem itself. I was very lucky to have Tiffany Malakooti design the book. It was such a special gift.

Olivia: Reading the book in public has been so fun, because absolute strangers will be like, ‘Wow, what is this luscious book you’re holding?’ Like, with a familiarity bordering on rudeness, I’ve had two different strangers ask to touch the book.

Precious: I love the reaction it’s getting.

“This book really is me forming my own language, because I don’t even know where I’m going [laughs]. But I’m still trying to figure it out.”

Olivia: I am so tickled by that. I know this is your second book of poetry, and I’m curious—how has your process changed, and how do you feel it’s stayed the same?

Precious: It’s interesting because it’s a book that took a lot of time. In the earliest poem in there, I’m 23. At the end of the book, I’m 28. Something that influences the way I think about practice and my work is Heidegger’s On the Way to Language. And this book really is me forming my own language, because I don’t even know where I’m going [laughs]. But I’m still trying to figure it out.

Olivia: A vocabulary that I learned from you and from your work was this idea of ‘Pataphysics, the physics of imagination. What does ‘Pataphysics mean to you now? And has that journey also changed in the process of finding your own way to language?

Precious: It was what I studied in college, because I went to a very strange little school that allowed me to do that. So it’s kind of my whole praxis. I view myself as a ‘Pataphysics existential detective.

Olivia: A ‘Pataphysician.

Precious: I’m a ‘Pataphysician! One big thing for me in that type of practice is witnessing how I experience myself in the world, and creating portals in my imagination, but then also actualizing them. The book starts before I even have a serious practice of artmaking. Which is interesting to me, because a lot of these poems become installations. Some of my installations are named after these poems, and are trying to create specific portals that these poems are the language to; are the keys to.

Olivia: This reminds me of a Violet Spurlock interview where she talks about poetic logic, and whether poetic logic is inferential or deductive. And I was really struck by that way of diagramming it out; that deductive logic comes from a desire to order the world instead of discovering it, and that poetic logic is a bit more inferential, and it has more tenuous and contingent ideas. So I have always been kind of curious about how you see mystery as it relates to memory, versus a traditional investigation, versus intuition.

Precious: A lot of it for me is working through a feel-knowing of something. Luckily for me, my body is not the only place that I live. I have access to my dreams. I have access to all the things and people that have come before me, and that information lives through me. And it is this non-coercive rearrangement that shapes the way I see the world. I can go to a place where I can make rituals. I can make spells. I can talk to things that can help me access these repressed memories. It’s hard to go back to a place that you can’t remember clearly, and I also think that every time you remember something, you’re remaking it in your mind. And that’s why poetry is so big to me, because these are the keys that I leave to go back to that place.

“The poetry stems from memories. I’m trying to get back to something that’s left my body. It’s really one big ritual of time and love. And in there, maybe we can play? It’s devotion.”

Olivia: One of the questions I’ve been dying to ask you is whether you see a kinship with the figure of the Griot. I know Touami Diabaté died recently, which really shook me up because I’m a harpist, but the main reason I’m a harpist is because I can’t be a kora player. And you talk about your practice in this shamanistic, scientific way—connecting the moon, the stars, words, history. It feels emblematic of the Griot tradition. I wonder, where does that figure/archetype sit with you?

Precious: I am so happy you asked that question. So much of my work practice and spirit is influenced by amazing mystic scholars and shamans, people for whom it’s not even a way of art-making, but an actual practice of lived life. The poetry stems from memories. I’m trying to get back to something that’s left my body. It’s really one big ritual of time and love. And in there, maybe we can play? It’s devotion. And the rest is God.

Olivia: But Did You Die? feels like a Grimoire, animating the space as it’s being read and carving out its own existence in air. Both in this work and in your conceptual art and the more psychosexual food-art, you play with these ideas of life and death and time. I’d really like to hear you talk about the idea of duration.

Precious: Time is my favorite medium. Because most of my favorite things I get to make are living. Whether I make a garden, or like, a crazy, invasive garden that can’t be put back into the earth. So I have to burn it all. And then the ash gets another afterlife. So I’m constantly thinking about the afterlife, explosions, never-ending rotting. Maybe because I’m such a physics nerd, I view time as something that moves with nature. Poetry really helps because it’s an archive space. It kind of works as time travel.

Olivia: Have you seen The Last Angel of History? This meta-archaeological, time-traveling—

Precious: —Yes! The John Akomfrah movie. Love John Akomfrah. What a cool cat.

Olivia: Yeah, poet of the archives, absolutely.

Precious: A master of time-outside-of-time. ’Pataphysical traveler. It reminds me of that Roland Kirk song, “Theme for the Eulipions.” It’s a really good song about time travel.

Olivia: Is there a musical component in your creative life?

Precious: Music is so big for me. I work with this person named Gio Escobar from Standing on the Corner. Kelsey Lu did the soundtrack for this show I did. I play the harp, we should play together! I’m kind of a classical music nerd. I’ve reworked [Olivier] Messiaen’s “Quartet for the End of Time” several times now. It’s been played by all-Black quartets. Music is something that echoes in a lot of what I think about. Music as time-travel. I think about those three years Thelonious Monk spent on the road that nobody knows about. [From the ages of] 19 to 21 no one knows where he is. Where was he? What was he doing? Someone needs to do some critical fabrication about that, because I am so curious. And then he came back, and he was formed! He was Thelonious Monk!

Olivia: Similarly, I think a lot about how there are all of these photographs of Aretha Franklin, and she’s holding a camera.

Precious: I’m so curious about her archived footage!

Olivia: There are so many photos where she’s just holding this camcorder!

Precious: Witnessing.

Olivia: What was she filming? What was she seeing? What were the moments that felt important to her? It keeps me up at night. What is on those tapes?

Precious: Release the tapes, literally.