In ‘Swallowing the Sun,’ on view at N.A.S.A.L. in Mexico City, the artist traces the curves of human-made design at all scales

In northwestern Saudi Arabia, along coordinates that touch the Red Sea on the east and the desert on the west, they are building “the future of urban living”: The Line. A 170-kilometer-long, straight, um, line, that will be a 200-meter-wide, 500-meter-tall fully mirrored prism with schools, health clinics, and luxury stores—a live-in mall. The promotional materials for the pre-planned city promise that it will fulfill people’s well-being by prioritizing its nine million inhabitants, instead of all the transportation and infrastructure that takes up space “unlike traditional cities,” anything anyone could need will be within a 5 minute walk. To prioritize all the imagined denizens of this $1.5 trillion mall, 20,000 Howetait locals are being forcibly displaced and, as has become common in the region, immigrant workers building The Line report abusive and inhumane working conditions.

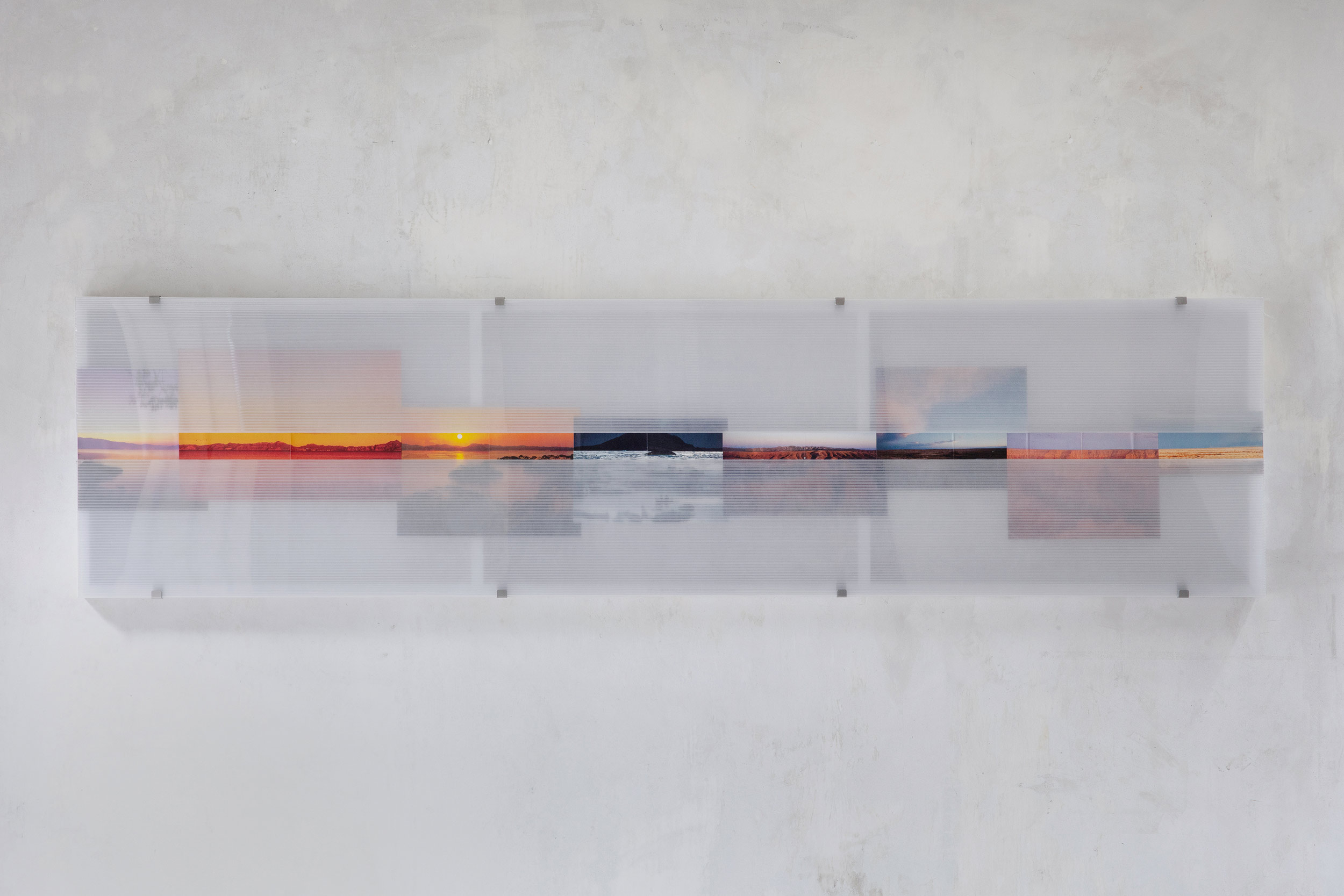

This ungodly project betrays the simplicity of its name through its sheer complication, ugliness, and impracticality. But viewing Swallowing the Sun, Enrique Garcia’s incisive first solo exhibition, on display at N.A.S.A.L. in Mexico City, I finally grasped how The Line’s stupidity ran deeper than that. Its very linearity pretended to stand against the true gospel of contemporary productivity: the curve. Garcia’s exhibition presents six new wall works combining found photographs minimally altered—enlarged, cropped, overlaid—with sculptural elements like corrugated plastic and metal rods. While the compositions are largely rectangular, they combine their industrial, logistics-adjacent materials with images of winding highways, bulbous clocks, Mayan goalposts, coiled snakes, and solar phenomena. In them, the line is revealed as a perversion of the winding forms that have come to define contemporary life. The only straight line in Garcia’s images appears in Límite Poniente (Western Limit, 2024), composed by joining eight landscape photographs; semi-obscured under corrugated plastic, only a thin slice of horizon remains visible on each, as if they were one scene. The conquerable horizon line, once the imagistic fuel of future-oriented progress embodied by ludicrous projects like The Line, reads quaint in Garcia’s collage, like the product of a by-gone era when we were naive enough to believe everything on Earth was there for our boundless gobbling.

As one steps into the gallery, Machinic Drift (2024), the highlight of the exhibition, meets the viewer head on. It’s a large-format mixture of photography and sculpture, neither entirely tridimensional nor bidimensional, a strange object. Two white snakes with delicate yellow markings slither together, knotted and perfectly centered in a black background. The frame is divided in proportional thirds: up top the muscularley middle mass of the silvery serpents, at the bottom their sharp little faces with roe-like red eyes. Bisecting them, a provocation represented by a section of conveyor belt; metal rods meant to spin in place as they advance commodities in their assembly-line process towards finished products; a type of skin for the body of endless productivity; a dermis that is used for transportation, as is the serpent’s. Swallowing the Sun seems to incriminate the snake. It is as much a recurring motif throughout the show as serpent symbolism has been in cultural production for millennia. At some point in history, serpents became a stand-in for our own ambivalence toward knowledge. We can agree knowledge is a wonderful thing to have when it comes to aiding our survival, and the Rod of Asclepius—a staff entwined with a snake—serves as the universal symbol for medicine. The way serpents shed their skin can mirror how knowledge opens our minds to potential renewal and cyclic re-invention. But too much knowledge is sinful; the biblical bite of the apple stirred the hubris of believing ourselves capable of knowing it all, of objectifying the world and everything in it.

The rest of the works extend Garcia’s inquiries into man-made design, its surfaces and its constant reverberations with nature, but specifically, I believe, with the serpent and its circumvention of rectilinearity. Garcia plays with this idea of surface and dermis by masking his found-photograph assemblages with corrugated plastic, achieving an effect that is almost holographic—the wavy translucence adding a layer of vibration, a tension that is augmented by the overlaid grids of his compositions. Erosión Doble (Double Erosion, 2024) articulates this well with its large-scale, twin portraits of tires, their symmetrical, zig-zag threads exposed to the viewer in enlarged tight frames, evoking the POV of lying under a massive truck. The left tire is overlaid with images that heighten the connection between the “man-made” and the “natural,” categories that collapse into each other at every turn: a precision-tool on top of a skillfully sculpted marble human figure, partially obscured by a high-contrast black and white image of a railway, gracefully turning on a shoulder of empty landscape; a small branch of erythrina coralloides or colorín tree, crowned with a bright red flower that grows in little clusters of fang-like petals. The right tire sports a nascent highway at its center, a roundabout growing exit and entry runways in four directions; to its left, a sewing machine-precise seam, and to its right, a god’s eye view of an over-water bridge. The juxtapositions in other pieces, such as clockworks and ants, craters and ergonomic chairs, further emphasize this conduit between the formal acuity of nature, the elegant coincidence of its needs with its products, and design and its materializing capabilities.

While the curve might seem like the most natural form—so distinct from the clean lines of early modernity and, now, The Line—the curve, its avoidance of head-on clashes and friction, is also the consummate surface of logistics. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney describe logistics as the capitalist science of efficiency that “toils to dispense with the subject altogether.” Logistics is the contemporary discipline in charge of the extended process of achieving the capitalist dream: that profit can multiply itself without labor, without obstacles or interruption. It’s the dream that value can leave behind the ups and downs of the market and the whims of bureaucracy to achieve the purity of the direct line, of progress and endless growth. But as Garcia’s engrossing composite images prove, we humans are too devoted to the curve. A chromed, luxury rectangle erected in the desert, no matter how linear or emission-free, is still the opposite of the core principle of logistics: “the minimization of the use of resources.” We love sideways and stupid.

In Garcia’s work, the apparent enmity between the indirect meandering of curves, and the direct, relentless forwardness of linearity is re-framed as the two sides of the design coin, the cyclical flip-flopping that shapes our long-tread material path. Some humans yearn for a logistics-ruled world without friction, where the subject abdicates in favor of the object through loyal compliance, willing to live in a mall in the desert, willing to displace and dispossess for their own comfort, willing to turn a blind eye to every cost. Swallowing the Sun reminds us of how a linear understanding of progress is very much ingrained, a consequence of our ambiguous, part-Promethean, part-Gaian constitution. Garcia’s image-assemblages point towards the alternate recurrence of eras of maximum advancement and unpredictable contraction. To engage with this exhibition is not to choose between technocratic ambition or folk-local resignation, but to realize that we obviously need to deal with both. The death of the subject is not nigh—and we will create all the friction we want.