A new zine and exhibition provide a glimpse into the rich archive of intimate portraits by the late photographer

The late Baltimore-based photographer Steven Cuffie’s personal archive had been left untouched for years when his children Marcus and Morgan Cuffie began digging through his cache. While they knew their father’s journalistic and professional work—much of it shot for the City of Baltimore as an official photographer—they were surprised by the breadth of the artistic photos he’d taken in the 1970s and ’80s. Portraits of women both clothed and undressed, in the studio and in domestic spaces, the photos balance pensiveness with insistent human presence, a kind of consideredness which suspends moments and produces intimacies.

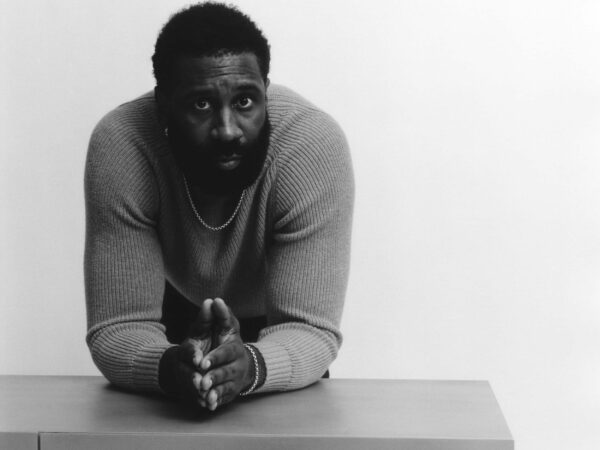

Today, numerous boxes of prints and negatives reside in Marcus’s apartment. In an effort to share the collection, they curated the first exhibition of their father’s work for New York Life Gallery in 2022, and currently three photos and a number of negatives are on view at the gallery again until July 27, pegged to the release of Karen, a 26-photo zine of one of the women whom the elder Cuffie depicted in 1979.

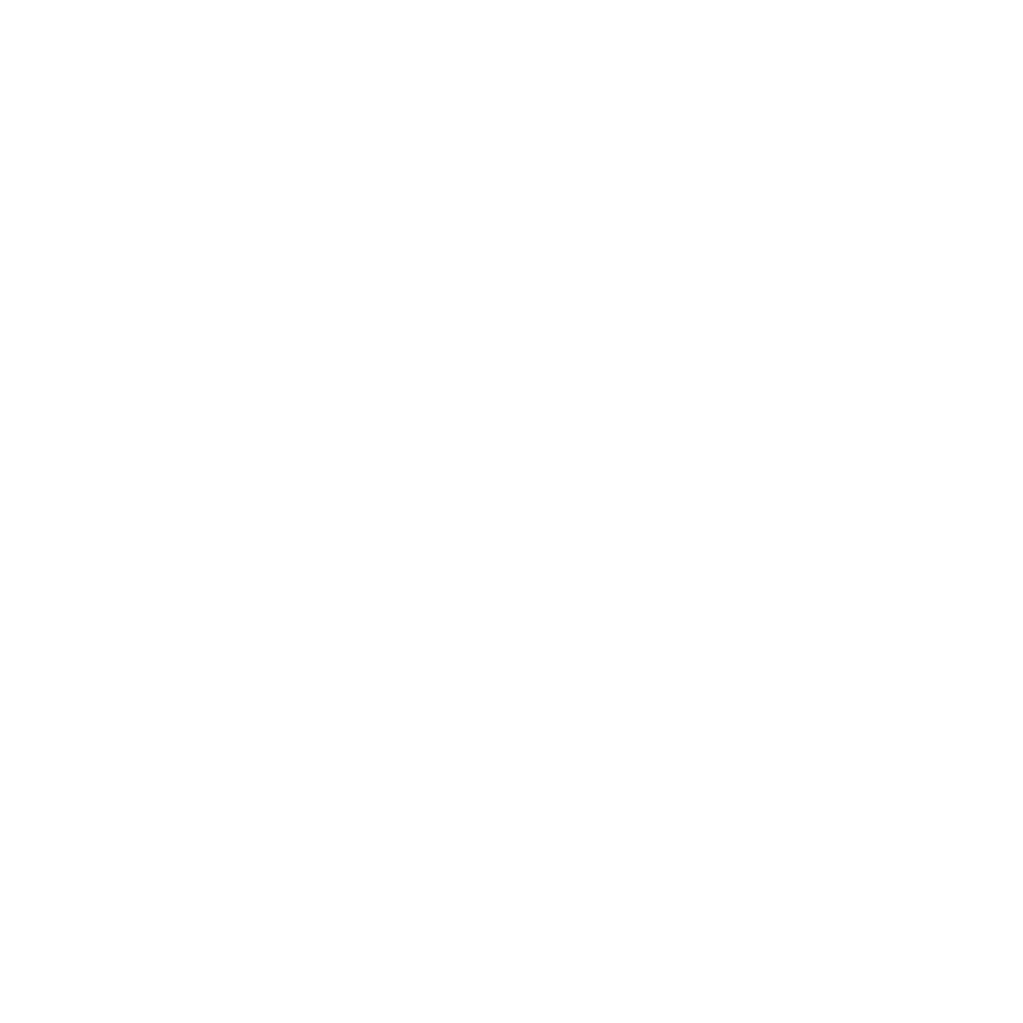

While poring over these archival elements in the Chinatown gallery, Document spoke to Marcus Cuffie about the process of discovery and recovery and about expanding their relationship to their father through his art.

Drew Zeiba: What was the process of bringing this work to life? When were you going through the archive and were like, Let’s show this?

Marcus Cuffie: My sister and I went down to our house in Baltimore. We were packing it up because it was being sold. I think it was Christmas of 2018. My dad had died in 2014, and we came back up with a bunch of his prints. So we started going through them.

Growing up, our dad was a photographer, so we saw his work. But this work is all from the ’70s and ’80s, and we hadn’t seen it before. Partially because a lot of it is erotic photography or portraits of women that we didn’t know. And a lot of the early images also featured my mother. Those works were from when we were younger, but they had been kept in boxes, unseen. My sister and I started going through them and were like, Oh, these are actually really amazing photos.

When we were growing up, our dad was a photographer, but he worked for Baltimore City. His photography was utilitarian. He was taking pictures of the mayor at public events, construction, things that were needed for the public record. And he took portraits of children and our family on the side, but we thought of that as more of a hobby than anything.

I did some research, and he had been in a few group exhibitions in the ’70s, but by the time he would’ve been married, which was the early ’80s, none of his work was being shown. There’s also no real record of what was in those early exhibitions. The only thing I’ve seen was in this literary magazine in Baltimore called Chicory that was put out through the library—which was mostly children’s and teenager’s writing and poetry. They would get different photographers to do the covers. That would’ve been when my dad was in his mid-20s. Some of his photography is on the cover of those. But a lot of this work has been totally unseen.

Once I started showing some images of the prints on Instagram, other people’s interest led me to think, Oh, something is possible. Ethan James Green [of New York Life Gallery] and I started to chat about the work, and at the same time a friend of mine wanted to do a portfolio of my dad’s work in a magazine. At that point, I felt I could show the photos and begin to have a proper archive. Before, it was at my sister’s or still in Baltimore, but now I have all the negatives, I have all the prints that he made in my home. I have the full body of work. There are probably 1,000 prints. And then negatives, I have probably 20 boxes, each having 300 negative strips in them. I’m still going through it.

A lot of what was in the first show were portraits of women. And it was all work from ’74 to ’85, because I felt in that period he embraced the idea of being an artist the most.

Drew: The exhibitions and zines have focused mostly on nudes and portraits of women. Is that the bulk of the work? Or are there other threads?

Marcus: There are others. The nudes and these portraits are only really from the late ’60s to the early ’80s. Past that, it’s pictures of the city, portraits of children. The portraits of women and of children are probably the two largest bodies of work. Then there are events around Baltimore. I’ve been focusing more on the portraits of women because I think those are the images people connect with the most. And I think they’re also the most distinct. Because when I was thinking of other photographers working at the time, and specifically other Black photographers, you don’t really have another Black photographer working in this erotic, intimate space, especially not in the ’70s or ’80s. You have Black Power movement images. And you have Blacksploitation imagery of Pam Grier and people like that, which would’ve veered into the erotic. But those things relate to these ideas of Blackness, whereas I feel my dad’s are more personal. Also, coming from a fashion background myself, and with Ethan who runs the gallery also being a fashion photographer, it seems this has been the work people are attracted to and understand. So I’ve tried to make a clear body of work as a starting point for getting it out there.

Drew: Getting the photos out there, do you feel you’re detaching from it a bit—as in it could be anyone’s art you’re passionate about? Or do you feel like it’s a way to relate to your father differently?

Marcus: It’s been nice to connect with the work because he was making a lot of it in his late 20s, early 30s. So our ages overlap. It’s interesting to think about my dad working in parallel with me. I think it has definitely helped me connect with this idea of him more as an artist and to see the things in his work I’m attracted to and find this appreciation for it.

I feel like I have this detachment from it, where I do look at these things purely thinking, ‘What image is the most interesting?’ But I also choose images that don’t veer too much into feeling exploitative. I think when I was first going through the work and showing the images of women, I did have this anxiety because I didn’t have names or years for a lot of the work because I hadn’t gone through the negatives yet. I did ask myself, ‘What is my responsibility to the women in these images?’ I know some of the work had been shown and printed, so obviously he was going to show it or at least was in the process or conversations with people that would have been aware of it. But I didn’t want it to look like I was showing my dad’s personal erotic images or something. I tried to position the work differently, and to select the images that give a more rounded feeling.

Drew: How did you begin to find out who some of these women, like Karen, were?

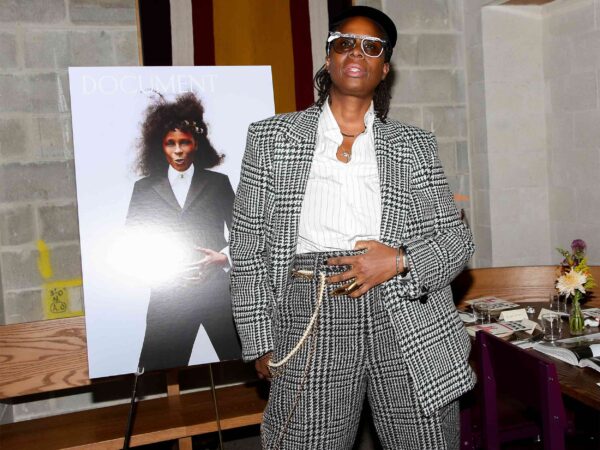

Marcus: He’d write it on some of the negative strips. Karen was the first woman I came upon where all her negatives were labeled with her name, the day, and the year. I would say two thirds of the archive is labeled. Some might have the location or year but no name. Some aren’t labeled. Karen, I don’t even know her last name, but some I do.

When I was doing this zine, I was like, How do I start to build on this imaginary narrative? Because I don’t know my dad’s relationship to this woman. And obviously, some of the images can be quite intimate. So it was like, How can I make a collection of these images and a small publication that might begin to build a narrative for who she was? Because I feel like that respects what she means inside the work. I want to expand on that with some of the other women, like this woman Katrina, who features a lot in my dad’s work. Her photos are usually labeled and named. But they tend to all be nude and in the studio, whereas with Karen, she was in her home. There are some studio shots, but hers are primarily in her home or outdoors.

It’s also interesting because I think there are some different periods where I see my dad working in the studio, or I see him working in homes—there are these different threads. There are these different moments in the work where my dad was exploring different things.

Drew: What was the orientation or vision for this particular zine?

Marcus: I wanted it to feel like you were following my dad while he was doing this. It wasn’t about, like, Can I choose the most singular images? But, Can you almost feel like you’re with my dad? It goes from outside to indoors and ends with these more intimate images of her on the couch. It becomes this moment of undressing. My dad was a very stoic and quiet person, so it’s interesting to look at these photos and be like, Who is this guy? This Lothario who’s fucking these women and having relationships with them? How can I put myself in this place and make it understood so that you can see his position in the photos too?

Drew: It’s weird, when a parent or someone like that dies, often people start telling you about them, and you get versions of this person and their impact on someone else that feels really alien from the person you knew—you start seeing them through others’ eyes. This project seems like both the same but also the inverse of that. You’re reinterpreting him through these moments of his life you weren’t there for. Did he ever tell you about anything you discovered in these images?

Marcus: By the time my dad died, I was 22. He was very supportive of my artistic career when I was younger, and I went to art school all through middle school, high school, and college. And a big part of it was because my dad was a photographer and he supported it. But we never talked about his craft. I did photo in high school, so we talked in a technical way. But in terms of what he was doing, what the work is about exactly, I don’t have as much context.

I was doing research and I found a photo of his in a children’s magazine, which had a Facebook page, and I reached out to them. Through that, someone who knew my dad contacted me and sent me this body of work that I guess he had mailed to this other photographer, who now lives in DC and is very old. I want to say it was like 12 to 15 photos. And the letter my dad had written basically explains the work; he was reaching out to this photographer to get a critique on it. But that’s the only letter I have that really talks about his interests in his work. He has a ton of journals, but his shorthand is so insane. He would journal every day, but they’re so illegible that I don’t know exactly what’s in them or if they give some keys to his explorations or what his ideas were.

He was young. He was an artist. He had a camera. You can get a lot of women to stand in front of a camera. And some of the things that happened may be accidental. How many of these repetitions are intentional? I do a lot of work on my own trying to understand what exactly the choices mean, but I also give my dad a lot of leeway in saying that I think he was thinking intensely about these things. Growing up, we had so many photo books with photographers from Steichen forward. He knew photo history. So I know those things affected his work—like Eadweard Muybridge, and other early photographers he loved, like Gordon Parks or Dorothea Lange. He had his influences and definitely was someone who looked at photography really intensely. So I do have that as a basis of like, Okay, I know some of what he was looking at. And one of the boxes of negatives has this whole collection of clippings, just different articles about photojournalism and interviews with photojournalists. I have some basis for understanding what he was doing, but a lot of it still has to be built just through me looking at the images and interpreting them myself.