In an interview with Harron Walker, the author Shola von Reinhold discusses the fabulosity of fabulation and whether some stories should be allowed to disappear

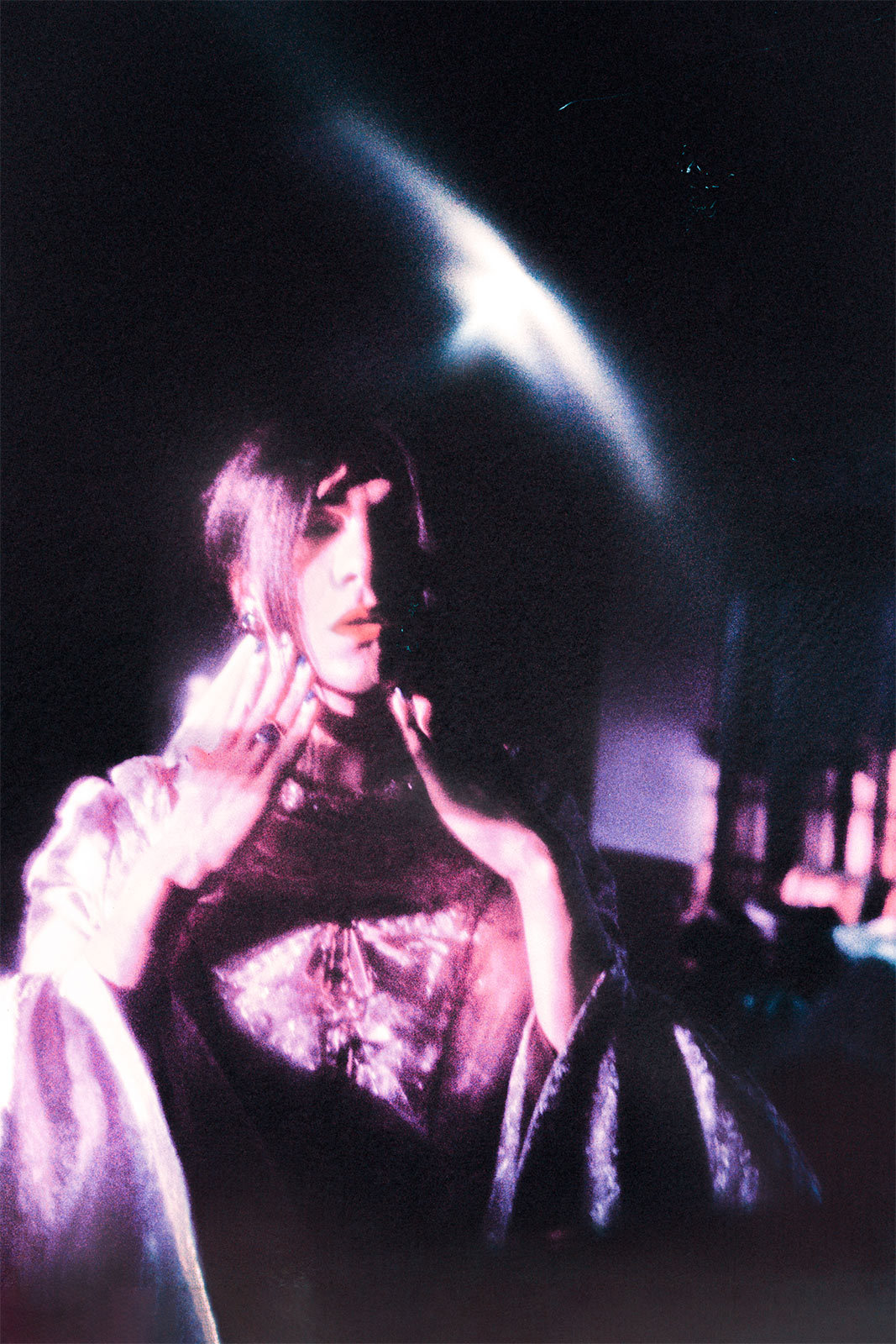

The novelist Shola von Reinhold is entranced by socialites and scammers, those diaphanous figures flitting in and out of the archive, sometimes, though not always, by choice. The pairing makes sense, the more that I think about it; socialite and scammer alike must master the art of social interaction should they hope to be successful in their craft, but whereas the latter uses that mastery to avoid surveillance, the socialite courts it, accruing a unique kind of capital in attracting public notice—though again, are we noticing all of her? Or only what she allows us to see?

Given this fascination, it’s no wonder that von Reinhold’s 2020 debut novel LOTE—an elegantly written mystery about how a canon is made—centers on a search for one such missing socialite, Hermia Druitt: a once-prominent Black artist and aesthete of the early 20th century who has been forgotten—or maybe erased? I adored LOTE when I first read it a couple of summers ago, so I was delighted to interview the Scottish author about socialites and scammers, history and erasure, those whom the archive remembers and those who’d rather evade capture. During our correspondence, conducted over email this past spring, von Reinhold revealed that she’s currently at work on a few different projects: a book-length piece of nonfiction, an exhibition of paintings and collages, and her second novel. “Someone clever should preempt it so I can finish it,” she said of that follow-up to LOTE. On other subjects, she was more withholding, like where exactly she was at the time of her responses. In one of them, she divulged that she was writing from a train that was traveling from one British city to another, but, the elusive écrivaine that she is, she wouldn’t share anything further. “I really find it useful for all sorts of reasons to be possibly everywhere at once,” she explained. “I tried to convince all my friends I’m living in Amherst after I had a weird dream about visiting there, but they didn’t buy it. Now, I want to go. I don’t know anything about it other than Emily Dickinson, but if someone wants to fly me out…”

She’s very keen to preserve certain mysteries about herself, and I’m more than happy to oblige. In an age when you can google seemingly anything, when governments track our every move, when Big Tech spies on our texts to determine which targeted ads we receive, maintaining the unknown can feel positively romantic. But back to the subject at hand. Our conversation began with the fictional socialite at the heart of von Reinhold’s novel and all of her historical counterparts who inspired her character.

Harron Walker: How did you come up with Hermia? Who are the socialites, past and present, who inspired her creation, or just inspire you in general?

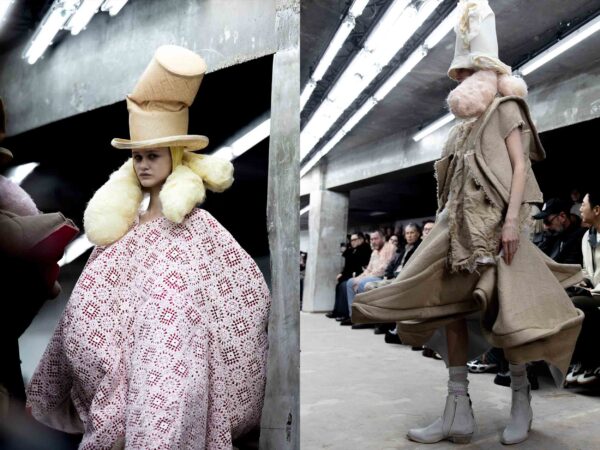

Shola von Reinhold: It’s a weird term—socialite—is it not? A weird phenomenon. Everyone uses it to mean wildly differing things, to refer to individuals at the heart of bohemian art circles and literary avant-garde milieus as much as those who dine at ultraconservative philanthropist brunches—though maybe these things are not always so far apart. Who or what constitutes a socialite? It can imply beauty and glamor, but it can equally be leveled disparagingly, among both the left and the right, to imply vacuousness, idleness, uselessness. A socialite is not a celebrity but can be, and I suspect when they become an actual celeb, they are less of a socialite. So, it’s constituted differently from fame, and that probably has something to do with labor. A ‘high society’ socialite doesn’t have to be an heiress or even a hostess, but there’s often an overlap concerning the latter: does a socialite tend to actually throw the parties or attend them? The socialite and the party girl aren’t quite the same, either. And are all club kids socialites? No.

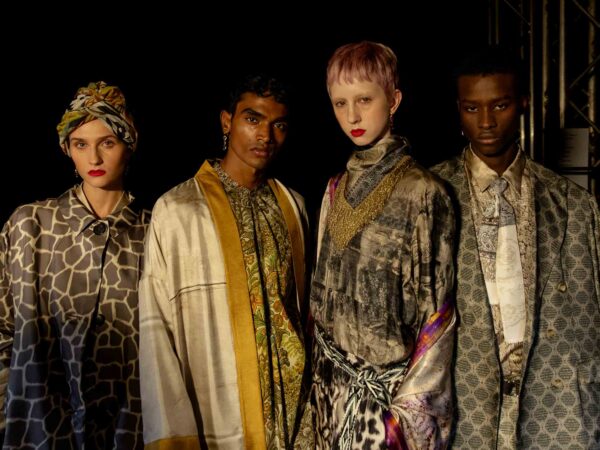

There are historical figures in LOTE: the Bright Young Things like Stephen Tennant, who was a queer socialite, an aristocrat, a scion to a sizeable fortune emerging from, more likely than not, exploitation, but who, like many of the Bright Young Things, squandered it rather than amass even more, to the horror of many. There are the ‘bohemians’ of the ’20s, who went to the seedier clubs, the artist-models and characters who might get called socialites, and the more romantic modernists in Bloomsbury. Hermia rose up from a seeming void in all of this on the one hand, and glimpses, flashes of Black figures moving in the archive on the other. Figures including the likes of the Harlem Renaissance writer and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, who, I feel, must go down in history as a socialite prolifique.

Harron: Do you consider yourself a socialite?

Shola: I don’t consider myself a socialite, I am a socialite, darling—is one answer. Another is, maybe someone writing and talking consciously about [being a socialite] the way I have here loses purchase on the actual thing. Then again, maybe not. Another answer is, no. Another is, it’s a fun, contentious, somewhat obsolete category to don and jostle against, a kind of play that, if only lightly, tears a few holes in certain social fabrics and exposes a few more holes already present in others, a few gaping voids…and many an aporia.

“Fabulation, or call it what you will, is not only something that ‘works,’ but these kinds of imaginative, creative, poetic relations to the past are crucial when it comes to seeking out, encountering further, those who had to live in such imaginative ways in the first place,”

Harron: How has becoming ‘Shola von Reinhold, the published author’ or ‘Shola von Reinhold, the author of LOTE’ affected your movement through social space? I’m curious how that might have broadened your access to various scenes or influenced your reception once you’re in those spaces.

Shola: Sometimes, it’s enjoyable and useful. Sometimes, it’s embarrassing, alienating. On the enjoyable side, I suppose there’s an almost magical process whereby you spend a lot of time compacting fascinations into a book and it becomes like a magnetizing spell, drawing in people with similar interests or passions you might not have met, or maybe wouldn’t meet for several years in the natural course of things. But in terms of a change in reception, yes, sometimes people literally transmogrify upon realizing you’re a novelist, as if they think you can’t remember them being awful moments before. But the vast majority of the time I find myself among people who aren’t really huge readers or followers of the Contemporary Novel™, and the ones that are aren’t bores!

Harron: What kind of scenes do you spend your time in these days?

Shola: I really daren’t talk about ‘scenes.’ Coteries, on the other hand…

Harron: Do you find it difficult to learn about socialites through archival means? I’d imagine that the lives of many, like Hermia’s real-life counterparts, have been totally obscured, whether intentionally or not. Were any of those figures obscured by the archive? How much about them have you been able to learn through your own research, and how many of the blanks have you had to fill in through what the scholar and writer Saidiya Hartman has termed ‘critical fabulism’?

Shola: Most, if not all, have undeniably been in some way harder to find in the archive because of the mechanisms of said archive. I’m currently working on a book that features some of those figures that I encountered during research for LOTE, like a Black artist model in London in the ’20s who was a habitue of dingy Soho clubs full of Thelemites and communists and the usual painters and poets. She lived, it seems, quite a high-octane, dizzying life. So much so, it’s odd she’s not even just a little more prominent. Anyway, I’d never have encountered her were it not for Hermia and LOTE in the first place. So, yes, fabulation, or call it what you will, is not only something that ‘works,’ but these kinds of imaginative, creative, poetic relations to the past are crucial when it comes to seeking out, encountering further, those who had to live in such imaginative ways in the first place that they get cut out of the picture.

At the same time, I’ve noticed that there’s a recent kind of popularity in looking for ‘lost figures,’ and—it’s not that deep, but—some of it I’m a touch cynical about. In the sense that you now have people taking up this mantle, engaging with obscured figures who they might not typically be interested in because they were obscured, because they weren’t part of the big picture. Once, only a certain kind of weirdo might have felt compelled to meet, through history, another person who exists on the archival fringes—not only because they were marginalized by economics and identity, but because, on top of it all, they were weirdos who lived through loopholes, existed sideways, and all of that is hard to account for archivally.

Harron: This got me thinking about how the archive is sometimes at odds with those who wished to live ‘impossible lives,’ as the historian Jules Gill-Peterson posits at the end of the film Framing Agnes: how the impulse to record and clarify their lives in exacting detail can be a violation. Maybe it’s not so sad that we don’t know everything about everyone who ever lived because, in some cases, our ignorance means those people succeeded.

Shola: I think often of some kind of technology, or poetic method, or combination of the two that would allow us to incorporate the past—figures in it, archives—into the present, so cohesively that time itself collapses, and about that being a kind of justice. The past—all those billions of experiences, sensations, ways of being, living—being allowed to operate in the present and therefore the future. I sometimes feel an acute rage after speaking to my mum or certain friends [about] how the poetry of their lives that exists in spite of so much is routinely devalued, diminished through the lens that capaciously retains other stories and ways of being. It’s hard to explain, but it’s something to do with the injustice of some of us being accounted for in the creative world or elsewhere and others being so far removed from that accounting that it knocks the air out of your lungs.

Harron: I also wonder about those people who didn’t get away with living their ‘impossible lives.’ People we can name and know every detail about. People we might call ‘scammers.’ Is a scammer just a socialite who got caught? It’s like two sides of the same coin in a way. Anyway, speaking of so-called ‘scammers,’ are there any, past or present, that you find particularly interesting? What do you think we can learn from their lives and how they lived them?

Shola: A great hero of mine is the international jewel thief Doris Payne. She is 93 and a Black and Indigenous woman from a mining town whose feats in the ’70s and ’80s earned her the moniker Diamond Doris. She would study fashion from her seamstress mother’s magazines, aware of the extra difficulties of stealing diamonds from Cartier and Tiffany’s in Monaco as a Black woman, figuring out ways to make it work to her advantage. I love the way she talks about what we might think of as ‘scams’ within her art of theft—the sleights of hand and glint and shimmer of moving and being and distracting. Drawing attention here to avoid it there. Doris Payne’s thefts are one of survival but also compacted by a deep political rage, hatred of the mining industry which sculpted her upbringing.

Harron: How do you want to be remembered or preserved in the historical record? Do you think you’ll have any control over that, or do you even want to have that control?

Shola: I suppose I already see how the historical record might preserve me by looking at things in the present: ways of recording, retelling, even socially—an inclination to reporting a version of ‘reality’ that is so banal, excruciating. One that attends to a reconstruction of drabness—a recapitulation of the worst order that sucks the poetry out of everything in a way that I see as deceitful. So, hopefully not that trash!