In this exclusive essay for Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue, the painter and filmmaker takes a look at the challenges on our horizon, and finds the potential for liberation in imagination

I consider myself an optimist. My transness, among other things, imparts a firsthand experience with the power of transformation and gives me a pretty hopeful point of view. Not unrealistic about stuff, but I generally keep a positive mental attitude. Now, when you get down into the fine print—take a closer look at the ole specs of my “P.M.A.T.” (Positive Mental Attitude Transmitter™)—you will note that the range on that thing is a little shabby. Meaning, it doesn’t project too far down in my calendar and is largely localized to my now.

You see, the future is something I try not to think about too much. To lift my head up from the now and all the hard shit that is happening and look out at the horizon can make me existentially seasick. The now is a pretty hard place. But that horizon? Can look downright scary. I know I’m not the only one feeling this.

I have a bunch of educators in my life, friends and relatives at all levels of teaching. When they talk about their students, they commiserate with affection and love but also deep worry. One story illustrates the burden our destabilized now is having on young folks. A friend/educator had taught a class with two students, one of whom had an emotional-support rat slated to join them in the classroom. The problem was that in the same class, another student also had an accommodation for their own emotional-support animal: a snake. Now that’s some high-anxiety, must-see TV there.

All the anxiety that young people are feeling these days is, in my opinion, wholly justified when we take a good look at that horizon and where we’re headed. Our future is built on a swamp of bad ideas, rotted ideologies like the “rugged individual, unfettered free-market capitalism, the nuclear family, and binary thought. The same crap that has brought us all to the brink of climate disaster, the war on bodily autonomy, and plutocratic rule. Everything that has been left at young people’s feet feels like some horrible prank: a flaming paper bag full of fresh shit waiting to be stomped out. Like, how did we get to a place where with all the advancement of science and the cataloging of the complexities and variety in nature that an entire political party seems to have adopted its impoverished understanding of gender from Kindergarten Cop? “There are only two genders,” they say.

What about intersex folks? Or folks with multiple chromosomes?

“Boys have penises. Girls have vaginas.”

Sigh.

To me, the growing prevalence of nonbinary identity in young folks is as much a statement of representation as it is a middle finger to this broken and outdated mode of thinking and the world young folks have been bequeathed.

When I was young, I didn’t think about the future because I couldn’t see myself living in it. I would proudly proclaim to my friends, “I don’t see myself living past 30.” That narrative fit neatly with my metal-head/punk sensibilities, but that wasn’t really the reason I felt that way. I couldn’t see into my future because, as a closeted trans woman, I couldn’t reconcile a future where I was so uncomfortable in my own skin. I didn’t understand this beyond an innate sense of myself; there were not a lot of resources (or even words) available to me during the ’80s and early ’90s that explained how I felt. All I knew was that I would eventually destroy myself.

But I didn’t! I don’t really understand why. It was pretty dang dicey sometimes. As I look back, I think one of the things that kept me around was my burgeoning imagination. My mom was a painter and a nurse. She gave my sisters and me the ability to look at the world in wonder. When we were kids, she was always putting us in art classes and encouraging us in our making, and in doing so gave me access to imaginary space where I could be whoever, whatever I wanted. This manifested itself in “pretend”—in plays and in comic books we would write and draw and also in the wholly imagined space of D&D. I leaned heavily on this ability, this disassociation. It became a tool for survival. I understood later that Mom had used her own art as a coping mechanism to investigate and help process her abusive childhood. Her paintings got pretty heavy when you understood the deep place they were being pulled from. But some were simply statements of perseverance.

I believe my sister and I absorbed that tool of processing for our own art-making. I believe my and my sister’s films are embodiments of that tool.

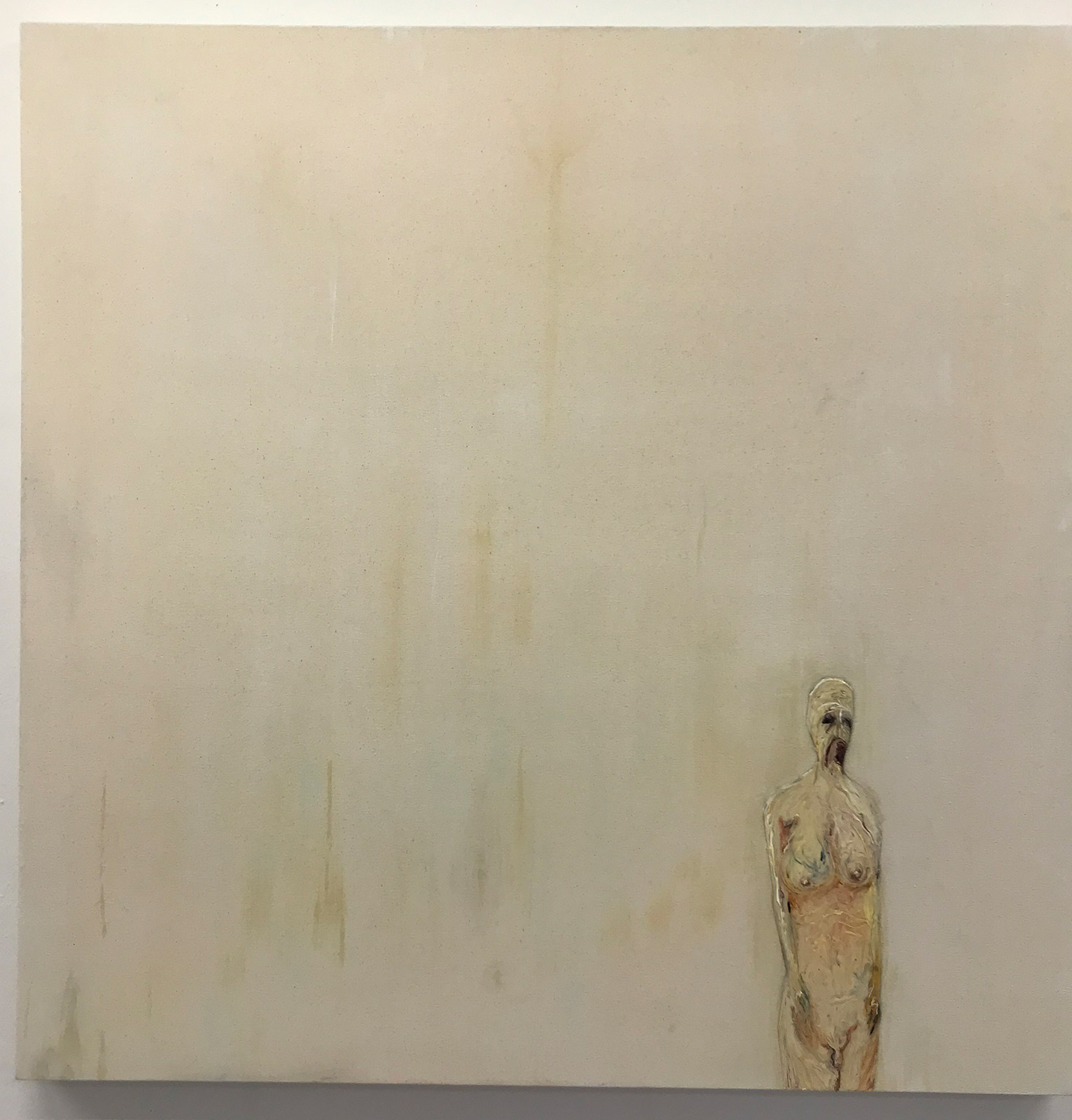

When I finally found my way out of the closet, I kind of left the business of filmmaking and started painting again with my mom. At that moment, my now had become very overwhelming. The road out of the closet for me was arduous and long. Like, really long! I’m a slow learner, okay! But rediscovering this new practice became a salve. The parts of me that I had held back for so long—all the blurry and fragmented, hidden pieces—were out in the open. It allowed me to see my complete self in my work more clearly because I was more complete. And I found new ways to express myself and my place in a world that can be downright hostile to trans folks.

And this is the true beauty of art-making. It is a way to fill up and counteract the vacuum of unmaking. It gives us access to dreaming and imagined space where anything is possible. If The Matrix is a story about liberation, it is manifesting itself in our imaginations as a template to liberate ourselves.

And in that liberation, is the ability to change everything.

Including what is on our horizon.

All artworks courtesy of Lilly Wachowski.