For his monthly column, Drew Zeiba traverses New York City in search of performances beyond the page

Does the work of a poem need to be limited to printed or spoken words? For decades performers, filmmakers, conceptual artists, painters, sculptors, dancers, and curators have proven otherwise. Still, lately I worried I’d been missing out on somebody “reading” by alternative methods when I bopped around town. Barring bad musical accompaniment (you probably do not need to back your non-scanning sonnets with acoustic guitar), defensive overacting, or semi-consensual crowd work, most of the readings I’d been experiencing this year had been giving poetry. (I am but one person—I can’t see it all, obviously.)

But last month—by happy accident—I ended up at several self-described literary events where “the poem” or “the book” didn’t content itself with being text on paper to be read aloud or read at home if read at all. Boasting looping animations, Jell-O wrestling, and ennead ensembles spread over serpentine soft sculptures (this last performance’s theremin I found more agreeable than a folksy six-string), May’s literary events got weird, loud, hypnotic, and even sticky.

Friday, May 3

Geoffrey Mak had his third and final New York City book-launch event at Paragon as part of the Writing on Raving series he runs with McKenzie Wark and Zoë Beery. He performed; mostly he stood, then danced, his disembodied voice pulsing with some beat over the speaker stacks. Destiny Brundidge and Alice Hines read. And hannah baer delivered what I guess I could call an essay but might better call a speech (in the sense of it being politically mobilizing rhetoric). Toward its end she invited the audience to join hands. Instead of closing the circle, this human chain folded. Doubled up, we strafed through the dancefloor such that by the end we’d have looked into the eyes of every other person. Before we started, as I grabbed her hand, I’d turned to M— to whisper, “I hate participation,” but it turned out I loved this. It was beautiful. It was humane. It was quietly radical. It was funny. I was moved.

Saturday, May 11

The sign by the elevator said six people could fit on, but every time more than five entered it emitted a harsh alarm and wouldn’t budge. This delayed me only slightly in ascending to the top floor of an East Broadway building (titanium knee, impractical shoes). I was there to see a play I’d received a last minute invite to: Goodnight Sweet Thing.

It turned out the play—directed by Cristine Brache and Sigrid Lauren—was based on a book of poems by Brache, which Blade Study co-founders Ian Glover and Brooke Nicholas had stacked before them. They said if I bought the pre-ordained copy from their pile I would win a giant golden egg, which sat in pride of place upon the folding table. I didn’t win, but at least I got a book (also titled Goodnight Sweet Thing, published by anonymous). I settled on a floor cushion for a bout of Jell-O wrestling equally psychoanalytic and psychedelic between Emily Allan and Betsey Brown, refereed by Joshua Widenmiller.

Brache told me over email that the idea to adapt her book for the stage came a year ago. “I wanted to be the first person to adapt a book of poems to theater and I was also curious to know what my poetry would look like in this form. After considering it for a while I realized that performance art is sort of like the poetry of the stage…and that felt like the best way to approach it.” For Brache, “the abstraction that performance art allows is very similar to what a poem can allow for when it comes to atypical or unexpected language/emotional articulation or play.”

By necessity, the theatrical staging added many voices to Goodnight Sweet Thing’s adaptation, including not only Lauren and the actors, but also Ryan Woodhall (sound design), Bunny Lampert (fashion direction), Atinka Anderson (hair), and Destroyer of Worlds (costumes): “Everyone involved was so magnificent to work with, each bringing such a wealth of distinct talent and identity to the piece. Everyone was also super down for whatever and no one was afraid of truly embodying the work,” Brache reflects. “I feel like the play is an expression of the book but also everyone involved.”

Wednesday, May 15

Inside Creative Time’s CTHQ on East 4th Street, sinuous sculptures by the artist and designer Riley Hooker snaked. Comprising yellow inflatable tubes cinched with faux fur fabric and cheetah and cerulean and umber cushions, the curvaceous arrangement might be called art, architecture, or, simply, seating (I mean, people were sitting on them). Hooker called it SIT(UATION).

On that Wednesday, SIT(UATION) served as the setting for the second staging of So Close to Human, a collaborative poetry performance co-initiated by Hooker with Courtney Smith (who also collaborates with Iván Navarro as Konantü).

Words became fragments, fragments unspooled with images, images echoed between speakers, their phrases looping and enlarging, slowly revealing new narratives, new turns. The eight speakers (I only recall recognizing Jeppe Ugelvig and Juliana Huxtable) projected their voices and visions from the cards Smith handed them over the course of 20 minutes. The piece accrued the textures of their particularities and the singularity of their being-together. They weren’t characters—as in a play—nor did they feel as if they were vessels. They were generators, conduits, friends, collaborators—or “participants,” as Smith called them.

Smith explained to me that she and Hooker did not compose the poem, rather “the poem emerges in the moment, composed as it is spoken out loud.” To create the underlying material of the poem, they collected from the participants “three short written fragments each extracted from their dreams,” which were then “pooled, processed, broken down, and organized according to the most objective principles we could apply to the language we received.” Eight equal parts were then returned to the “participant-dreamers” to produce the poem in situ.

“The entire verbalized process is the poem, and the participants are not at all performers—they are the dreamers and the re-dreamers,” Smith said, noting that the cards offer multiple options for participants, meaning participants make spontaneous choices. “In that sense, they are as much responsible for the result as we are. It is, in every way, a collectively generated work.”

Hooker said, “We are both interested in collective authorship, and making work that creates friction with the notion that any one person could ever own an idea,” adding that the collaboration with Smith came after he mentioned to artist Ignacio Gatica, a mutual friend, his desire to do “improvisational poetry event to play with and test the social dynamics of the inflatables I installed during my residency at Creative Time CTHQ.”

Monday, May 20

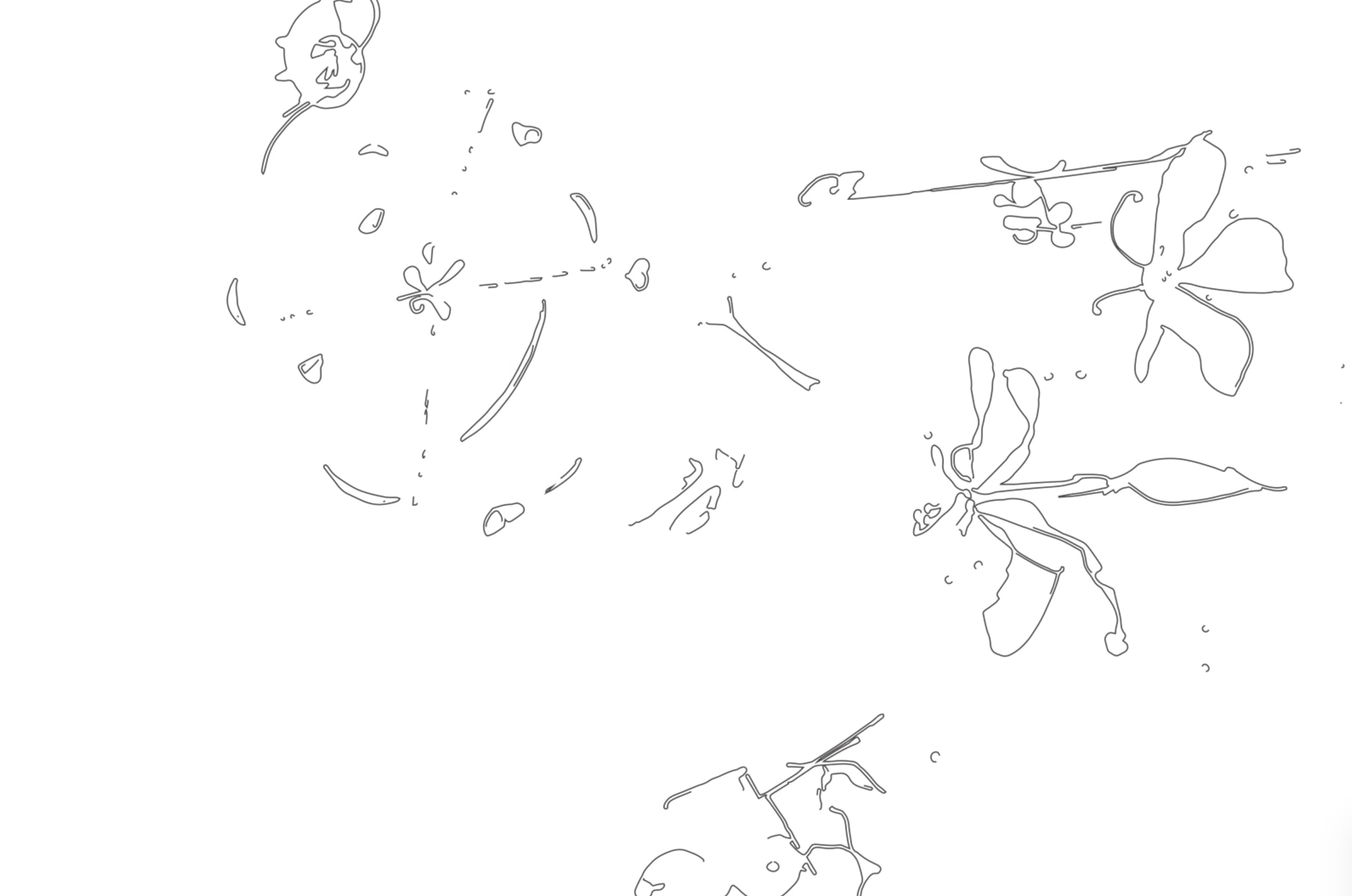

I snagged a seat in the front row for a double feature of Gia Gonzalez and Kaur Alia Ahmed at the Poetry Project. Gia Gonzalez read a really good poem about a person named Gia Gonzalez. Ahmed read several poems. Beside them a projection looped, black lines on white, like orchids, like phosphenes, like cell anatomy diagrams, like Rollercoaster Tycoon, like cursive. Cursive Paradise, their book’s going to be called. Coiling and curling, drawing and undrawing—but never undoing, just one thing that became another and still always remained itself. Word as line as time. “I’m going to read the ‘Soup Poem,’” they declared, and lines unwound over laughter.

As we ate shawarma on Saint Mark’s, I asked Ahmed how they made the visuals in After Effects and they explained it to me. I forget what they said.

Saturday, May 25

For the first time in maybe a year and a half, I journeyed across the river to Dumbo to attend the opening of Funto Omojola’s exhibition this my whole hole whole hole this still little me me me. Omojola is also a poet, and the title derives from a poem, but the show doesn’t feature any words; “When you have two mediums working side by side, they have to do different work,” they explained in an interview with me, published earlier this month, of the decision not to include text in the exhibition or photos in their forthcoming book. “And I think the images were doing the same thing that the poems were. So it makes sense that the work can split off and be its own thing that’s still holding the essence of what I’m trying to say in the writing. But I think they can exist differently.” However, there were two poems on the press release: one written by their mother, Abimola, and father, Olabode.

As the sun set, I Citibiked over the Brooklyn Bridge to make it to Metrograph, on Ludlow Street, for an evening of three films organized by Whitney Mallett of The Whitney Review of New Writing.

Catherine, directed by Dean Fleischer Camp and starring Jenny Slate, was an amazing short I had never heard of—an unnerving office dramedy, with the aesthetics and vocal patterns of 1991 instructional video. It felt almost like an exercise in pulling apart plotting’s mechanics: the film’s tension expertly rose by its estranging the stiffest professional interactions familiar to anyone who’s ever worked. Miranda July’s The Amateurist was also funny. But the evening’s raison d’être was the New York premier of Val, a film by Mara Mckevitt—starring Mckevitt, Emily Allan (again!), and Alicia Novella Vasquez.

“What the fuck does a movie have to do with readings?” you may be asking. Good question! Mckevitt’s film was but one instantiation of a life-art project that includes extended performances as her own boss “Val” (played by Allan in Val but played Mckevitt in a wig or behind an email account IRL) as well as her book Making Of, which, maybe in the tradition of self-reflexive documentaries like Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One or Burden of Dreams, documents the “making of” the film, but also, Mckevitt tells Mallett in Document, is the “control center” for the project while, recursively, the film’s script is the “urtext” for both.

If reading is seeing or sensing in time, if a book is a thing, if we write with “voice” and “image” and “line,” why should we expect poetics to end in language alone? Adaptations, control centers, duets, improvisations, performance art, movements, touches, drawings, dreams—texts in all cases find a way to be themselves by being beyond a singular form. How lucky we are to get to experience that together.