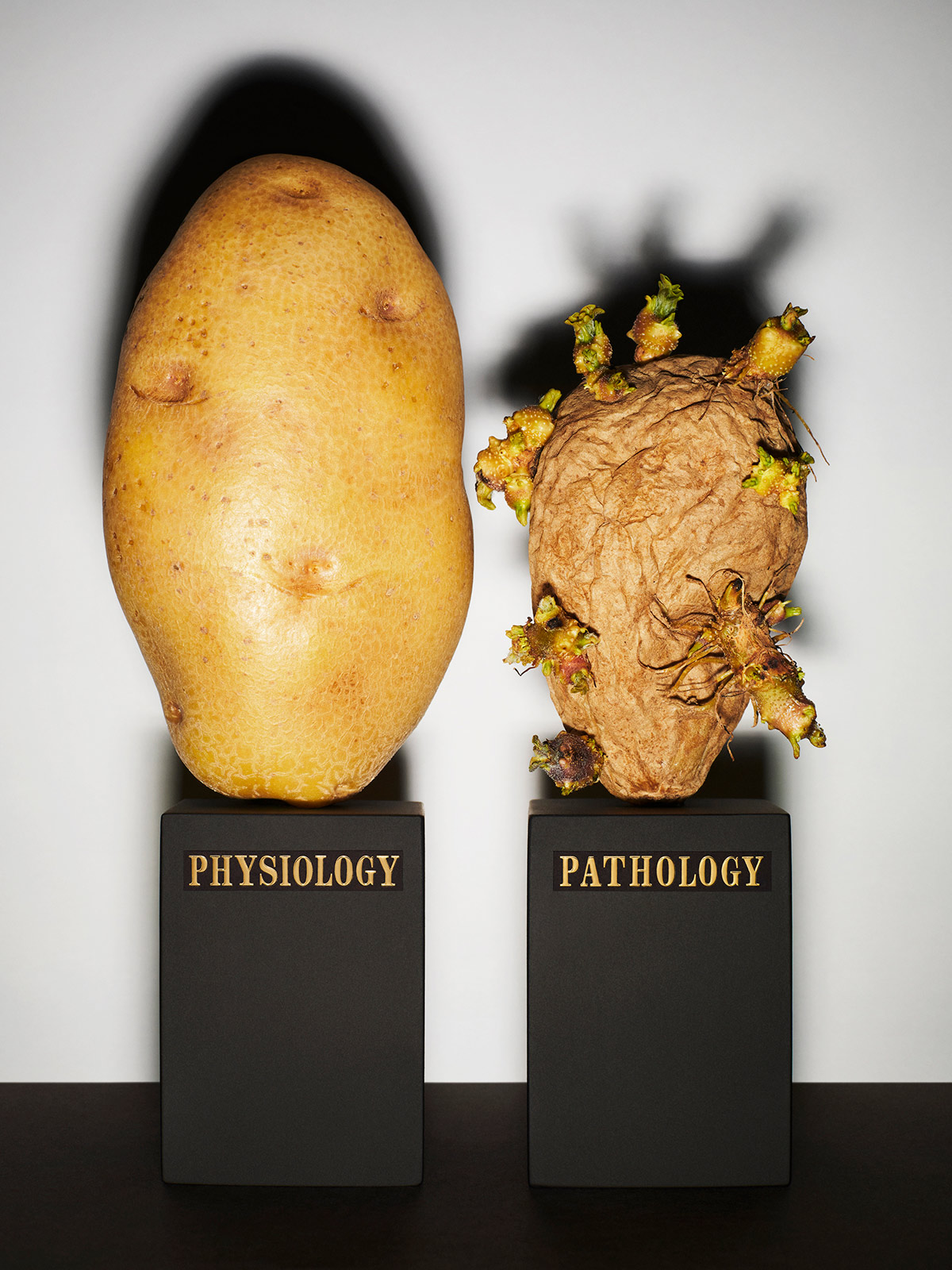

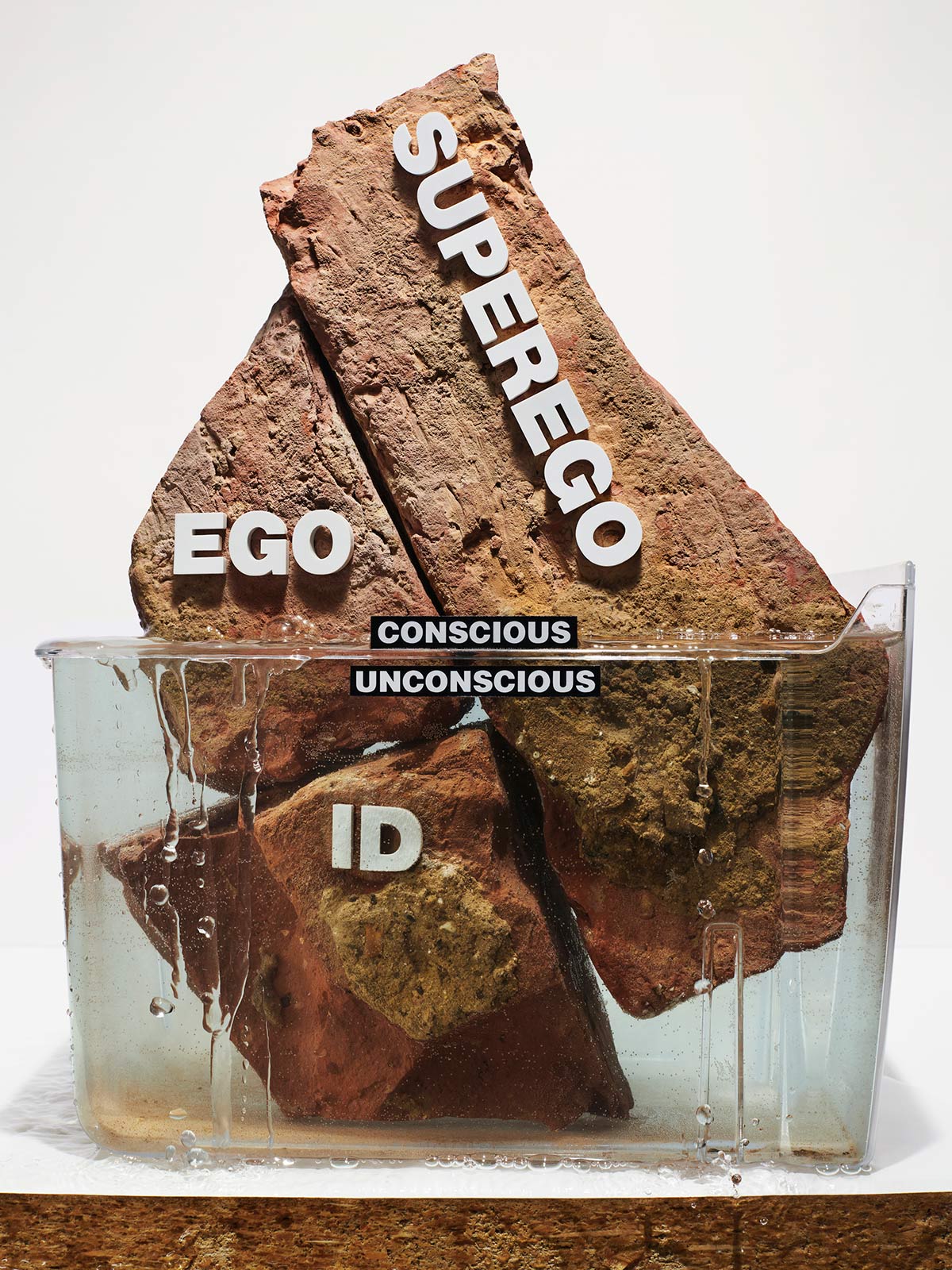

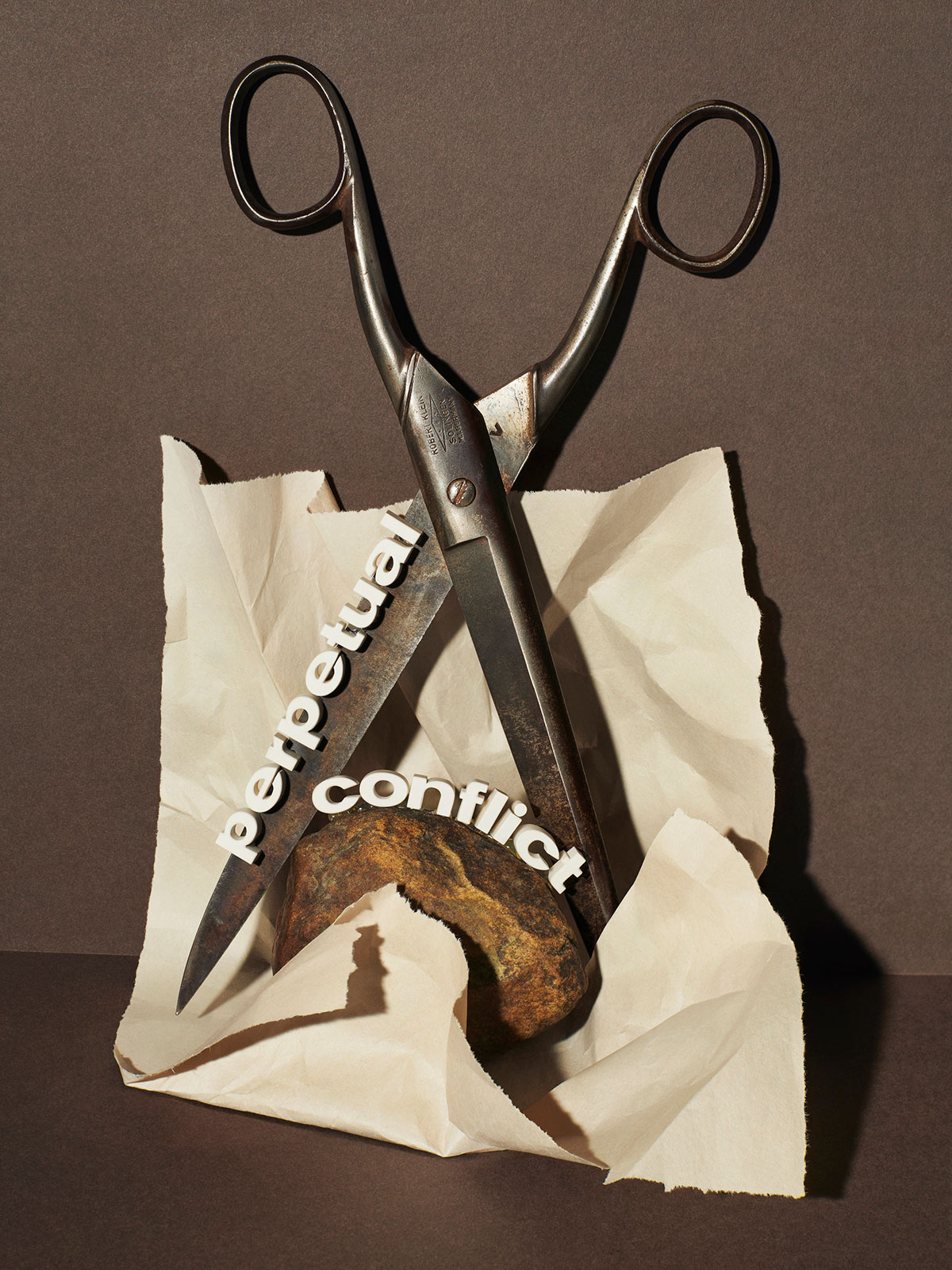

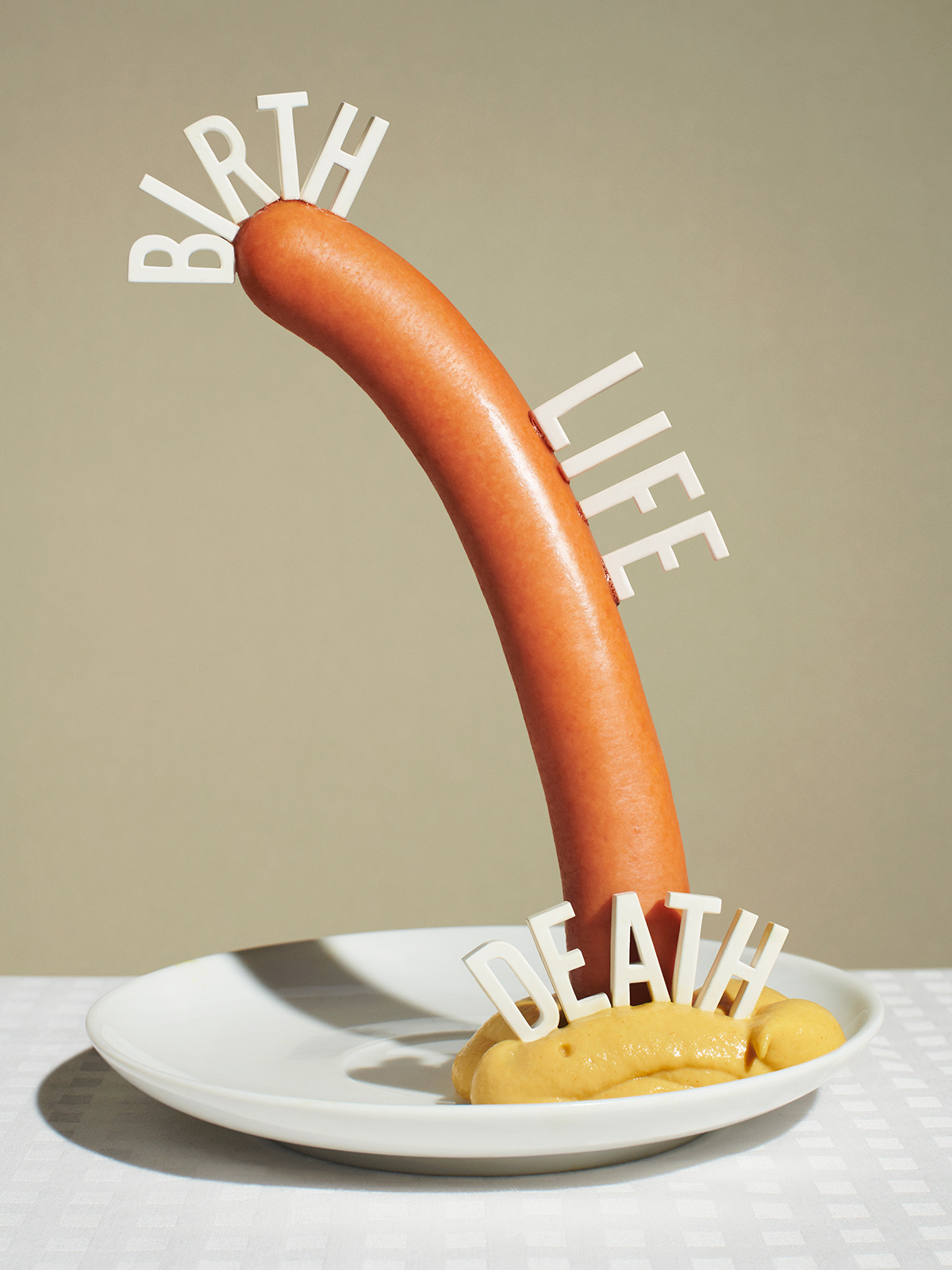

On view at The Corner Gallery in upstate New York, the photographer’s mischievous exhibition creates existential language from the everyday

Nineteenth-century writer Guy de Maupassant famously once said that the only certainty in life is death. For Vienna-born artist and photographer Bela Borsodi, the crux of that life is maintaining curiosity—about god, about semiology, about objects and their role in our existences. On view at The Corner Gallery in upstate New York, his photo series Birth Life Death suggests that inanimate objects have affects their own. In one photo, a fork labeled “SISYPHUS” balanced on an inclined wooden plank pushes a round root vegetable labeled “THE ABSURD.” In another, a pear wearing a gold nameplate necklace that reads “Salome” looms over a miniature plate displaying the chopped off top of another pear, on display like John the Baptist’s head in the original iconic Renaissance painting by Andrea Solario.

Birth Life Death presents non-living objects with mischief, humor, and verve. Regarding our existential situation amid what he considers an over-designed life, Borsodi reflects on the origins of his latest exhibition with Document’s Editor-in-Chief Nick Vogelson.

Nick Vogelson: Your show is called Birth Life Death. Tell me about the inspiration—how was it conceived? And how long have you been working on it?

Bela Borsodi: It’s a new body of work. I always liked the idea of having tactile words within an image, because as a photographer, you very often deal with the identities and the personality of objects and think about what they mean. This is something I’ve done before in my work where I put letters on things into my photography, but with this new body of work, I realized what I was really interested in was to play with meanings and words. I’m basically a little kid who always has the right three questions in mind: Who am I? Why am I here? And What’s going to happen thereafter? Another, What is this all about? These are the fundamental questions I think that every one of us had as a kid and we just learned to delude ourselves with concepts of god and philosophy and basically cheat ourselves [out of] a real, true answer, because there might not be a real, true answer. I wanted to explore certain meanings with that kind of aesthetic vehicle and that resulted in those photographs.

Nick: You talk about how this is a lineage of existential inquiry that stretches back for centuries.

Bela: Kind of. I mean it was not conceptually driven by that, but this is basically the only answer that I can have. Because these are questions that I will always find interesting. I randomly, for my own sake, pick things that I felt inclined to illustrate with this and to experiment with.

“We conceptualize so much about things. We give them personality based on how we use them, how we own them, and how we appropriate them. Now, that is basically their voice reflecting back on us.”

Nick: On the one hand, there are objects that you felt inclined to use, on the other hand, you readily acknowledge that they are objects that will one day make up the future landfill, so they’re all for the most part disposable objects. They’re not precious, but you’re tackling precious and timeless ideas. Can you speak to that a little bit?

Bela: Throughout my whole practice as a photographer and as an artist, I have always dealt with thinking about what things are. And I realized that very simple, ordinary things that you might not pay too much attention to—because they don’t stand out in your own idea about how you desire things to be—are more truthful, and more capable of engaging in big questions. It’s very hard to find an object that is not designed. You try to find a chair, and let’s say you do not have the budget for the real, real, real good chairs. You don’t find a chair anymore that you remember, perhaps, sitting in as a kid at your grandmother’s kitchen—a chair that looks like a chair, or a car that looks like a car, a cup that looks like a cup, a lamp that looks like a lamp. Everything is so designed. I think the things that do not obey these rules of our desires, whether they’re good or bad taste, have more qualities that represent what they really are and what they’re about.

We conceptualize so much about things. We give them personality based on how we use them, how we own them, and how we appropriate them. Now, that is basically their voice reflecting back on us.

Nick: How do you think simplicity belies complexity?

Bela: Well, it’s the biggest challenge, I think, for much art: to find a thing, a language that speaks very big, but is actually reduced to its bare minimum in order to be as accurate as possible. Extraordinary, complex things do not necessarily have to look very complex if they’re established as an artwork. They’re stronger when they’re simplified. I mean, how can you explain everything with one little thing? That’s where a lot of thinking is behind those images.

Nick: You also mentioned that something can be humorous, but not frivolous. How do you engage with humor in your work?

Bela: Humor is a very serious matter to me. If you can create something that comes across being humorous, it sort of tickles and challenges the audience. And anybody who might share the sense of humor I feel opens up to more easily and eventually gets it on a more profound level.

Nick: Would you tell us a little bit about Trinity?

Bela: That was one of the first images that came right away, I fell in love with it as I was sketching it out. Actually, give me one second [Bela goes to find his sketches].

In the end, there are three cigarettes smoking. That was my first true [inquiry] also—is it the Holy Spirit or the Holy Ghost? America is the Holy Spirit, the Holy Ghost is more ancient. I’m from Austria, which is still somehow a Catholic country. I mean, to some degree, even though my parents didn’t at all raise me Catholic, if you go to school, Catholicism is a big thing. Even as a kid, I was amazed by how much control this can have over you, and also how extremely humorless Catholicism is. I mean, Jesus never laughed in one story that I know. I thought, How can you trust a person that many people admire who doesn’t have any humor? What I tried to do was bring the humor back to something which is so big and so small, because the big picture of, I don’t know, a supernova doesn’t give a shit about us, or what we believe in. Smoking cigarettes is not a healthy or a good thing, as we all know. So to give those guys the chance to really represent the Holy Trinity… It’s like three guys hanging out, discussing our faith and the future and where we come from and where we go in a very modest little setting.

Nick: There’s another image with biblical references, the John the Baptist reference.

Bela: In art history there is Judith and there is Salome. They both are depicted with the head of a guy: one is Holofernes and the other one is John the Baptist. One of my favorite painters of all time, Lucas Cranach [the Elder], painted the same image of Judith and Holofernes like Salome and John the Baptist, but in that one the head is on a plate. And in the other, it’s carried by Judith with a sword next to it. That’s for the art reference part. The pear in its shape is very much associated with the female form. In this photo, it becomes this big mythological figure by chopping off the head of another of its kind, resembling the whole entity of this big story. It was very endearing to me.

I only did 14 of these artworks, I have five in my drawer that are ready to go, and hundreds more that I would love to do. It’s funny because usually every time I put my hands into something that I want to do, it gets extraordinarily complicated and time consuming in a way. With this one I remember thinking, How can I please come up with something that’s simple? I could put two things together, point, and shoot it, and it’s a great photograph. Technically, I’m equipped to do that, but that’s not the prompt. So I thought, I’m just gonna put the right shoe on the left, and the other on the right, or just take a carrot and force a letter into it and have it dangling. I realized that as much as I wanted to accomplish that, it drifted me to a whole different direction and became very complicated because in the end I need legibility. Attractiveness. And the punk rock aspect that I desired so much in the beginning was never really working out in a way. I put myself into a lot of work.