War-zone fantasies meet suburban poetics in ‘When You Can No Longer Speak, Sing Me a Song,’ the artist’s solo exhibition at No Gallery

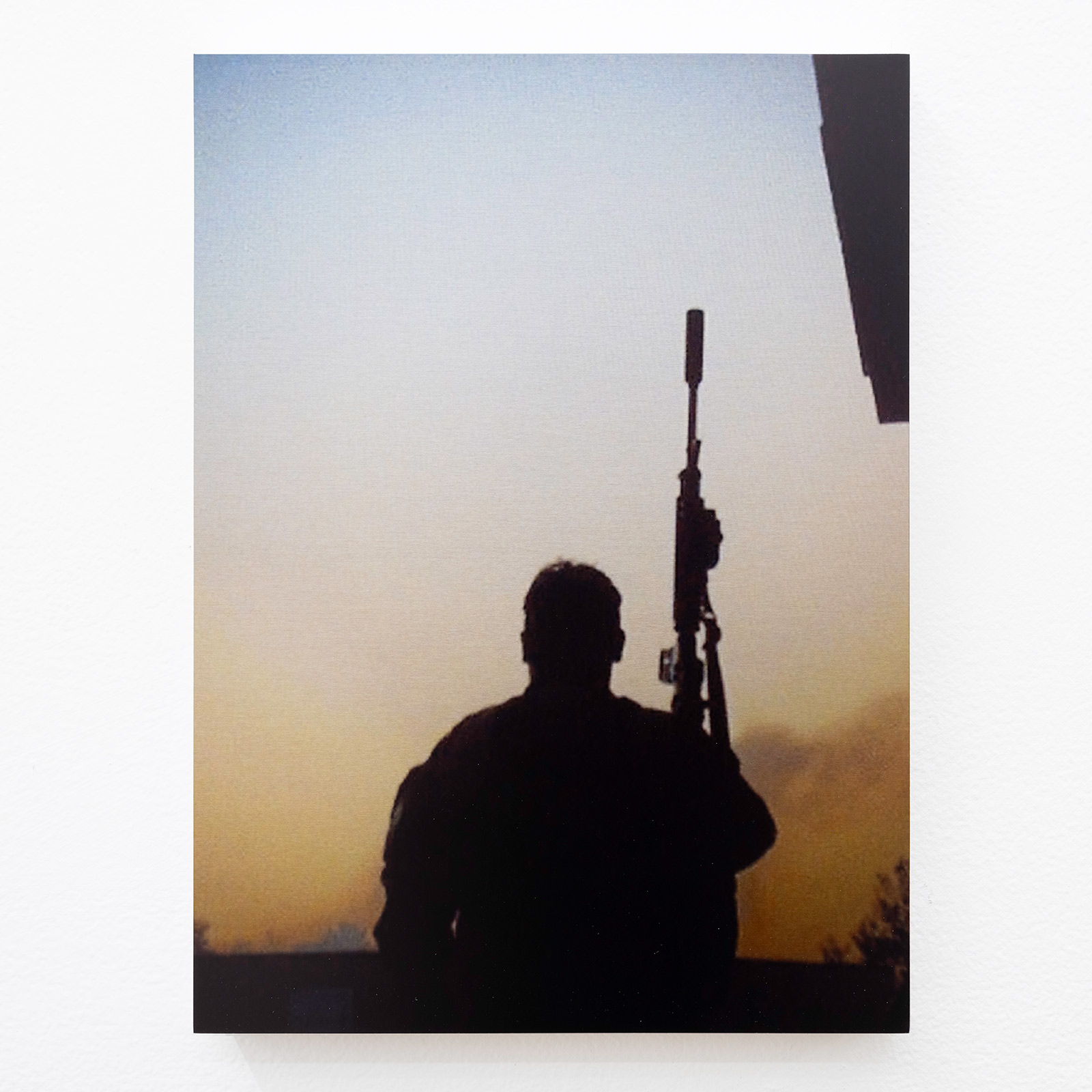

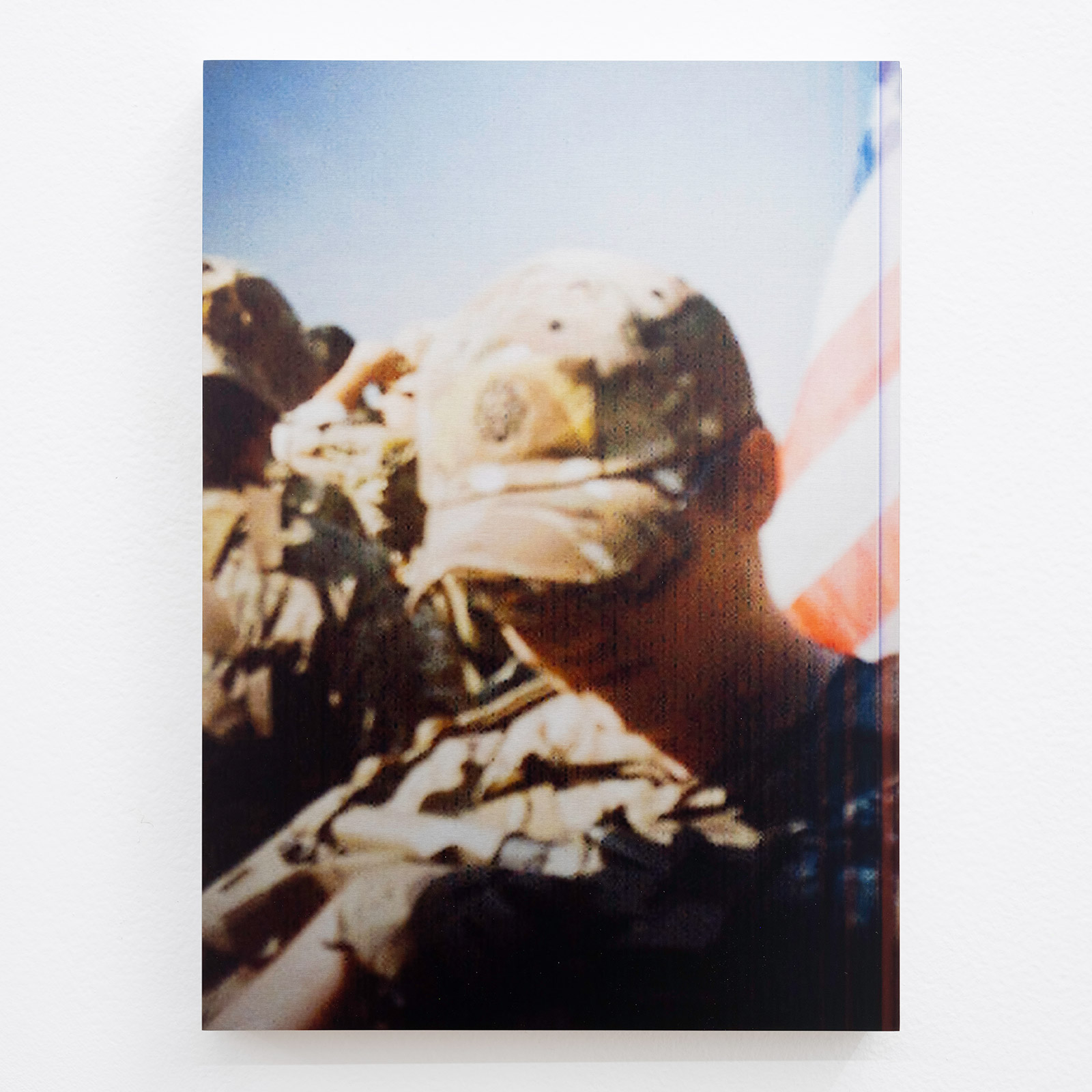

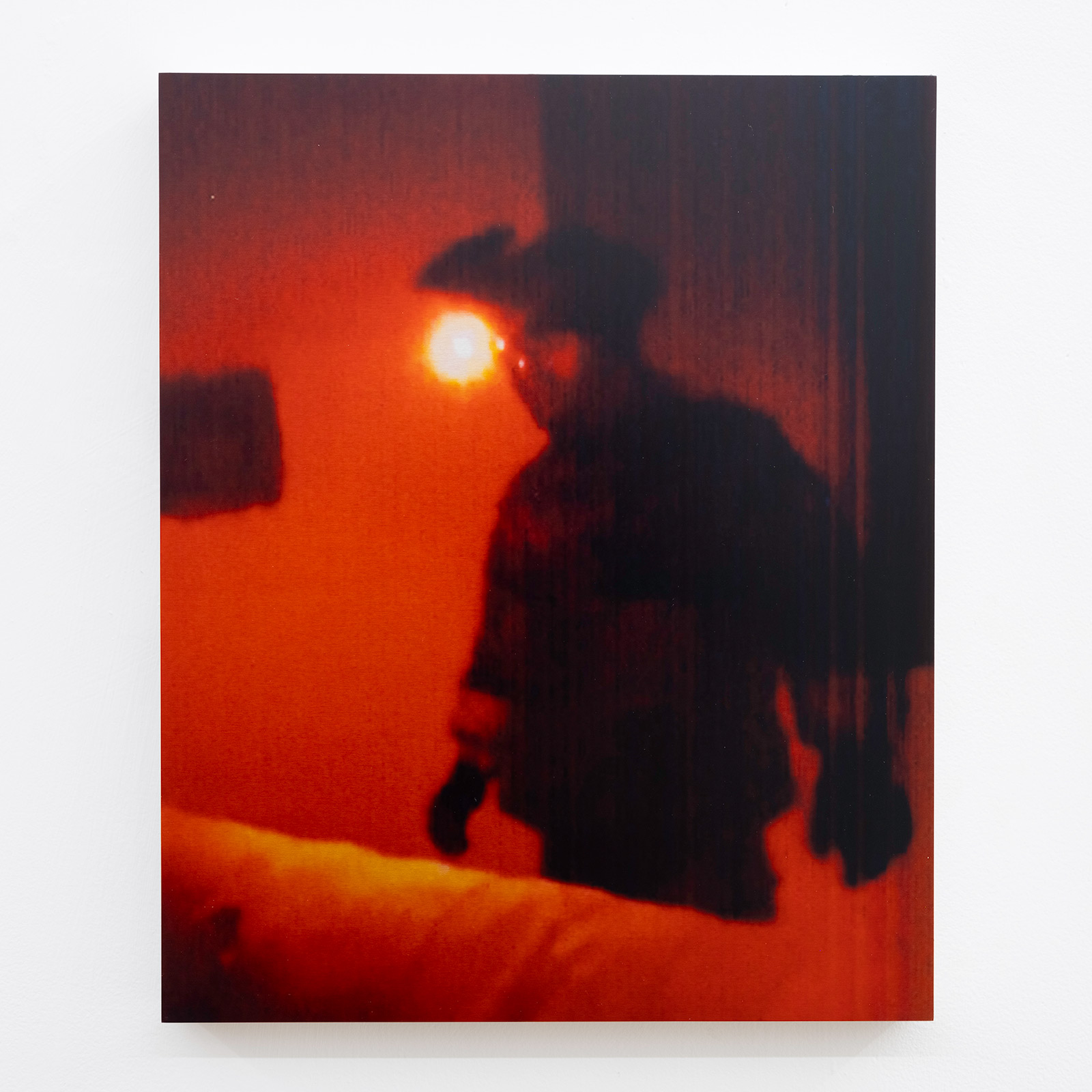

There is a war on display in the photographs of Ben Werther’s uncanny exhibition When You Can No Longer Speak, Sing Me a Song but it is not real. These images were taken by the artist while attending Military Simulation (MilSim) operations and LARPing (Live Action Role Playing) events across the United States.

Werther’s photos appear printed on aluminum on the walls of Chinatown’s No Gallery, as well as in a book, When You Can No Longer Speak, Sing Me a Song, published by New York contemporary art gallery Amanita. The book’s images are guided by a poem Werther wrote from the perspective of one of the last remaining artists of an America ravaged by airsoft LARPers. In this dystopian dreamscape, the battle waged is one for personal identity. Imagined violence and willful dismissals of reality occur both inside and outside of the artist’s book. Bloodless combat is a recreational activity, opening valves to creative expression and self-representation. Werther’s four-year project makes Play-Doh out of truth, history, and man’s search for meaning, not unlike the simulated soldiers he photographs.

Treating culture as an anthropological object is familiar territory for the artist, who has previously explored market-led nostalgia and collecting in his work on modern folklore, and its consumerist pedigree. With Yandhi (2022), Werther engraved 25-cent coins from each US state with locally circulated myths. Yanhdi considers conspiracy theories as inherently meaningful, a kind of premade language which runs through the culture first as a liquid, and then solidifies, elevated as sacred indisputable texts: xeroxes of ideology or scripture. He transferred handwritten notes left on parked cars onto canvas using ancient rubbing techniques in 2023 with Everyone is a Genius, pointing to the fetishization of analog aesthetics and the individual projection of meaning onto found historical objects. One person’s note on their windshield (“you park like shit”) is another’s message in a bottle. This February in the basement of Amanita, Teenage Tragedy (2024) played a chopped and screwed remix of Taylor Swift on loop, emulating the sounds typically produced in the bedroom studio of a suburban teen. To Werther, these audio productions are examples of attempts to recreate the past and its stylistic signifiers unintentionally transforming into something original, maybe even futuristic. Teenage Tragedy zoned in on cultural stagnation, commercial repackagings of the past, and the ripeness of these for political perversion.

Werther considers today’s modes of cultural production, particularly those with fantasy and reality slippage, as potentially the most potent and culturally significant art-making materials of our time. Before When You Can No Longer Speak, Sing Me a Song, he composed a manifesto concentrating on conspiracy theories, LARP, ARG (Alternate Reality Game), and fan-fiction; how these are utilized as scaffolding for building personal narratives and abstracting context. Functionally, these methods take what already exists and aestheticize it; the manipulation of real conditions to one’s imagination. The readymade’s sin was its literalism, its lack of production—a “non-art” object demanding to be considered an art object. The LARP responds to present conditions, recontextualizing and distorting them, calling new attention to them; things as they suddenly have footnotes. Can LARPing be the new readymade? For Document, Ben Werther asks this and the many more questions that tumble out of it.

Morgan Meier: You’re about four hours out from your opening at No Gallery. How do you feel?

Ben Werther: Can I sit on the couch?

Morgan: Of course. I feel like your shrink.

Ben: I’m very excited. This has just been a lot of work, and at a lot of times has felt like it’s running my life. Preparing for it, going to it, travel, meeting people. It’s been years. I’m glad it’s not going to be something I’m focusing on as an artist anymore.

Morgan: I want to start with the title.

Ben: I wanted the title to be a very Tumblr-sounding quote, like the edgy ones that get spray painted on a wall. I wanted it to have that very specific poetic, fake-deep quality to it.

Morgan: Real eyes, realize, real lies.

Ben: Yes, they obviously have meaning, but it’s also the aesthetic of meaning. It’s like a readymade caption. I looked at a lot of these and found one from some rom-com movie: ‘If we ever stop talking, send me a song.’ I liked thinking about this overly romantic content in the context of LARPing. The LARP being a kind of production that is real but not real, political but not political. These quotes perform meaning more than they hold meaning. I added my own spin, thinking about the relation between speaking and singing; speaking being this objective communication, while the song is communication, it becomes performative. And these expressions of identity that maybe people took for granted in the past, questions of personal identity and subjectivity now put under an increasingly big magnifying glass. Performing identity and perceiving identity—what used to be a speech is now a song.

Morgan: Do you remember first becoming aware of MilSim?

Ben: I saw people doing it a lot growing up. I used to play a lot of paintball with my brother, but I never really thought much of it. I’m from Nashville. People did a lot of airsoft things growing up—that’s pretty normal. I rediscovered it on TikTok during COVID through these videos of people wearing a lot of crazy tactical gear, doing crazy TikTok dances in their mothers’ basements, pile carpet all around them. This really suburban context but hyper-militarized to the point of fetishism. It appealed to me as something I wanted to engage with, but I never thought it would be something I’d do; it’s a big investment. But thinking about it as art, it became something I could investigate and experience. The first time I went I was not thinking of doing the book or doing the show.

Morgan: What was it about this world that drew you in? You’re entering first from a personal point?

Ben: A personal point, but also I think that LARPing and having a demarcated space where the whole point is to be someone that you’re not appealed to me—wanting to understand what that would be like. The feeling of not knowing what it was going to be, taking a left turn from myself personally and as an artist. I had to rent a car and go out in the middle of the woods by myself with all these people that I don’t know and stay there for days.

Morgan: How many?

Ben: It’s really intense, they don’t let you sleep, they try to make it as real as possible. It’s like backpacking, basically. They’re yelling at you. They’re all about two or three days. I attended four of them in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Tennessee, and Indiana.

Morgan: You must be signing serious paperwork. What were you thinking going in?

Ben: Yeah, they make it sound like you could die. But, you know, you can go for a walk and break your leg in a gopher hole. I was very nervous but also excited. I was thinking about drawing or painting, and the work that goes into that, this sort of labor of love and having to live with this thing, mark making. I started thinking of it as a labor but in a different context. Just go. Make friends. Begin.

Morgan: When does the idea for the work come into play?

Ben: It’s had different phases. I decided the easiest way to record it was to photograph it but I was nervous, I didn’t want to be the guy coming from New York trying to ‘get them.’ That was not what I was interested in doing. I tried literally everything camera-wise. I wanted the film ones that Kendall Jenner and influencers use; I wanted it to look like an Urban Outfitters advertisement. Commercialized nostalgia, very staged, but the photos I was taking were terrible. I took all this night vision footage and used none of it. At one point I was taking field recordings to transcribe them into a play… I mean, a cool idea, but not sure how interesting it would be.

“If it were just images it would just be me leaving New York and making something to bring back here. I’m not interested in doing that, or being a journalist. The poem gives it context,”

Morgan: Did the shift from attending as just another guy to coming in as an artist with a project change things for you, or with others?

Ben: No, they don’t care about that. Everyone there is recording it. I’m not special at all. One guy I met interviewed me! He didn’t have a gun, he was going around interviewing everyone with a GoPro. I thought, Oh, crap, this guy’s gonna beat me to it. He was very nice, he had cheese sandwiches. At these events naming it as a LARP is met with a response of ‘it’s not like that.’ LARP is a pejorative term used to strip someone of their identity. They want to dismiss that and those connotations. And I think with the question of exploitation, in the context of this, it is very expensive to go to these events. This is not a group of people that are exploited or have a history of exploitation.

Morgan: When did it become a book?

Ben: After a friend told me I was a text-based artist and that I needed to accept that. If it were just images it would just be me leaving New York and making something to bring back here. I’m not interested in doing that, or being a journalist. The poem gives it context, its dream sequence allowed me to pull from a lot of literary references that I wanted to project onto my experience and thoughts of what this was. Most of the work I’ve made in the past was made to be viewed as one but they always get separated. Making a book you can make the work serially and it will always be viewed serially. The prints are standalone, they have their own material, which you will see.

Morgan: Talk about the decision to print the photographs on aluminum.

Ben: They are matte-dye sublimation printed on aluminum and mounted on museum boxes. The image is burned into the aluminum and there are no whites, so the whites appear as metal surface. They have this sort of interior light. I like the metal, I like the idea of it, this shimmer and reflective quality. This question of divine light is a big theme in the book and a lot of the images. They are objects, and they feel more like small paintings, or artifacts, or screens.

Morgan: Was making the images appear as real as possible your intention?

Ben: I didn’t want it to be that way initially. I wanted them to be like Tumblr photos, I didn’t want body-cam photos. Body cams are incredibly loaded and, in my mind, [are mainly] about curtailing authoritarianism and this question of checks and balances. I feared these would overbear the ideas of fantasy production, and creating images that look like historical images, that look real but aren’t real.

“You’re obsessed with history, you’re obsessed with how history will look back on you because you’re worried about the future, and the lack of future. This becomes what people really mean when they say reality; reality has become hard to understand.”

Morgan: Do you consider MilSim old or new?

Ben: What makes this history is that rather than being historical reenactments, it’s about subjective memory, memories of war and violence. For some people this memory is a video game, it’s historical fetishism, or they really like American Sniper and this ‘heroic guy from Texas’ narrative. These fixations that are historical but not in a way that can be dated, they are from the subjective past. It is productive and subjective, and art-like.

Morgan: And maybe examples of the more slippery versions of reality today, where we could lose our feet a little?

Ben: Well, to me, this question of truth or reality really concerns the future. This canceled future Mark Fisher talked about. You’re obsessed with history, you’re obsessed with how history will look back on you because you’re worried about the future, and the lack of future. This becomes what people really mean when they say reality; reality has become hard to understand. And that accounts for my obsession with nostalgia or nostalgia culture as a kind of political concern.

Morgan: Were any part of MilSim’s politics, affiliations, or renderings of history a cause of concern or consideration for you?

Ben: At the beginning of every event the guy who organizes them makes everyone do a pledge: ‘I’m a silly war nerd who plays silly war games and I am here at a very big party with my amazing friends and their amazing costumes.’ They hire people to photograph the events and sell the photos back to you like Splash Mountain. This is really not political for these people. It’s only political because I’m like, It’s art. This is more of a fascination with the hero myth; I don’t think it’s political, it’s more of a universal truth.

Morgan: What were some of your influences or reference points?

Ben: A lot of Lovecraftian stuff, Joseph Campbell. When I was thinking, What is it I’m making beyond just being someone at these events? I wanted to create a hero’s journey narrative, and that is the dream-sequence poem. Actually, Lana Del Rey was a huge influence, I was going to call the book Born to Die. The way she constructs personal mythology is a perfect example of what this is and the question is, how does she get away with going to the Waffle House?

Morgan: She themeparks America but then, are they themeparking war?

Ben: Of course, they want combat and war but they don’t actually want war. I think you say ‘combat and war’ and then you mean actual war and I don’t think those are the same. People want conquest. They want the mythology around being a warrior. Take someone like David Goggins. He is an inspirational writer who is not really Mr. Military, but the appeal is he has produced this profound meaning in his life. The military becomes a vessel for that but it’s not actually the military. It’s about the production of meaning.

Morgan: This story is told from the perspective of the last remaining artist attempting to construct meaning from a desolate America at war. Is this you raising a flag, a warning?

Ben: Yeah, of course. The line ‘where everything is known and there is nothing left to be understood, where there is no joy left to seek, and thus no art left to create’ I think about a lot. People are not interested in making art from a place of fascination. Actually, I just have a fear that people will stop making art from a place of fascination. The film Hard To Be a God [2013] was another big influence. It’s about these scientists who go to a planet identical to Earth, but it’s in the future and it’s the dark age. I liked that plotline. I do think there’s a little bit there. I mean, the new dark age, right?

Morgan: Do you think art can save our souls?

Ben: Do I think art can save our souls? Probably not. I wanted to make art about LARPing as a solution to this dark age and to me, it’s hopeful. If all we can make are reiterations of the past, and the only thing you work with is the historical narratives that surround us right now, then how do we lean into the extreme? The extreme is becoming fantasy, becoming something new. I think it’s productive for people to do this. This is an example of people who are creating solace for themselves, and they are also making something new.

Morgan: You say the past, but isn’t one of MilSim defining features its unobservance of history?

Ben: When I say the past—I’m making the leap in my brain—I mean memory including personal memory. People making work about the past and the memory of what already exists. Jackson Pollock would not be making work about the past, he was trying to make something new, it was literally about making what doesn’t exist and only that. People don’t work that way anymore.

Morgan: Elaborate on larping as a readymade.

Ben: Well, first of all, I liked that statement, but I was thinking of the way identity is packaged and repackaged, when personal mythology becomes more of the creative act and maybe that’s the art, and I don’t need to see your painting. I think we have reached an extreme of that. I mean, there are examples of this. Who’s the guy who got on the boat and sailed away? [Laughs] [Writer’s note: that guy was Bas Jan Ader]

Morgan: Will you LARP again?

Ben: I am always LARPing [laughs]. Will I go back to these events? Oh yeah.

When You Can No Longer Speak, Sing Me a Song is on view at No Gallery from May 30 – July 7, 2024. 105 Henry St. #4, New York, NY. The photo book can be purchased directly from Amanita or No Gallery.