Document visits the luxury knitwear label’s founder Saskia Dijkstra and brand director Wies Verhoofstad in their 17th-century Amsterdam HQ

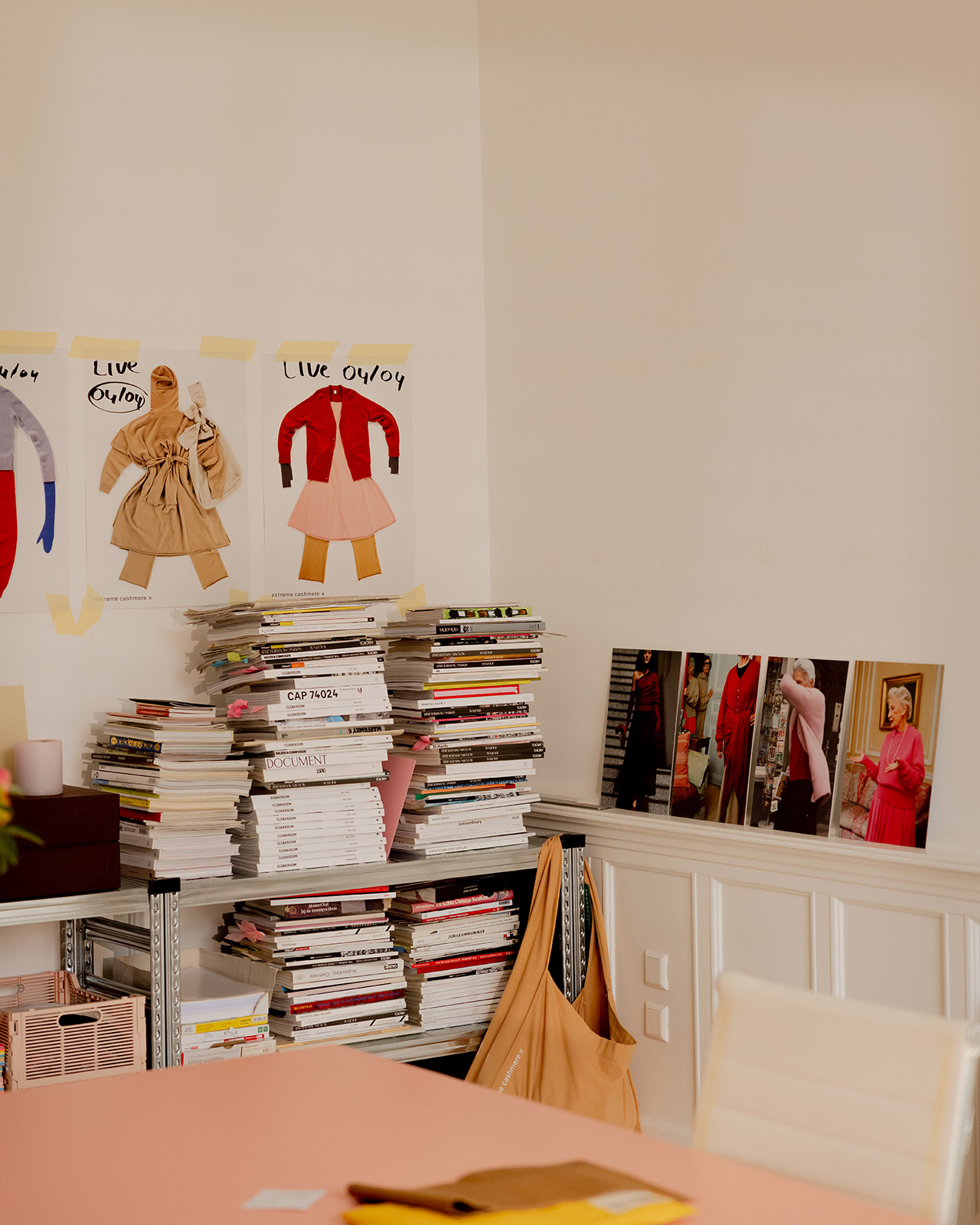

Stepping into the Dutch brand Extreme Cashmere’s central Amsterdam office is something like entering a minimalist cottage-core dreamscape. The knitwear line’s core team, each dressed in a Extreme Cashmere look tailored to their aesthetic, work from a 17th-century converted home on the Prinsengracht canal. Sky-blue hues and cashmere-draped sofas fill an expansive design room. A kitchen with stainless-steel appliances opens up to a crimson-walled dining room, filled with peonies and pink roses with a Delft tile fireplace on one end.

Down the hall, a series of local chefs—some on staff and others, including the pair behind Michelin-starred fine dining restaurant Zoldering, hired for special occasions—prepare light dishes using local ingredients. In-season white asparagus is topped with hazelnuts, basel, and a fresh strawberry sauce. A homemade chicken liver paté comes with marinated rhubarb. Extreme Cashmere’s young staff of 20-somethings sits down daily to share plates overlooking a picturesque back garden. The image would be cult-like if the energy wasn’t so laidback.

“I don’t like concessions in life,” says Saskia Dijkstra, the brand’s founder. It shows.

The luxury knitwear label, founded in 2016 and now in 300 stores globally, is the product of a simple desire: after over two decades spent producing cashmere for brands like Jil Sander, Dijkstra was still looking for the one sweater created with no compromise.

“We made millions of sweaters and there was really never one I liked,” sighs the Rotterdam native sitting in a spacious, canal-facing entry room. “Because it’s always about margin. It’s, ‘if we need it looser, then the weight goes down and the price goes down,’ so we can use shorter fibers.”

Extreme Cashmere sought to break away from quality compromises. “Our sweaters are heavy. Dense,” Dijkstra explains. “People say, ‘We want it lighter.’ But lighter is not better quality. People make it lighter to get the price down. If you want a lighter sweater you should use a different yarn. Because if you knit it looser it will pill more.”

The resulting cashmere garments are one-size-fits-all and genderless. Color is a focus. Think fire-hydrant red, pale pink and a bright forest green. Tightly knit sheer baseball tees hang alongside oversized (depending on height) cream pullovers, perfect when paired with the brand’s loose knit trousers. The brand recently introduced ultra-fine cashmere dresses. One staffer even mentions wearing her cashmere shrunken cardigan to a rave a couple weeks before.

“I think it works in the past, it works in the present, and it will work in the future as well,” Extreme Cashmere’s brand director Wies Verhoofstad says of the choice to remain unisex, monofiber, and sizeless. “Because it’s simple but you can be very creative.”

The pieces are made in Hangzhou, China, by one of the factories Dijkstra represented for so many years before founding Extreme Cashmere. “I was lucky to work for a factory which was very niche and they had fantastic, skilled people,” grins Dijkstra. “[Today] our technical guy can look at the samples of sweaters and exactly say, ‘That machine is not well and the washing is 30 seconds too long.’ To make sweaters like this you need those people.”

The hope is to change public perceptions of cashmere. (Why can’t it be for young people? Why can’t you wear it in the summer if it is very finely knit? Did you know that high-quality cashmere can go in the wash?)

Extreme Cashmere is also working to dismantle long held stereotypes around Chinese craftsmanship. Ninety five percent of cashmere comes from Northern China and Mongolia, explains Dijkstra. “It’s nice if you do the production in the country where the raw material comes from,” she continues. “So, lambswool is very strong in Scotland and the UK. But cashmere is in China. They know.”

Close relationships between production and design are essential. The knowledge held in production may be the greatest element missing in design decisions today, leading to an array of sustainability and quality issues. Tightening these connections and sharing the benefits opens up a range of possibilities on both sides, sustainable growth being just one.

“For the future, there is so much to do because most of the people in the world have no idea who we are,” says Dijkstra. “There are still so many people to dress.” Verhoofstad concurs: “It could work out that we stay really true to who we are and still get bigger. I feel like this is a luxury not many brands have.”