Document asked 15 critics to turn philosopher Roland Barthes’s 1950s magazine column on its head for its Spring/Summer 2024 issue

Throughout the mid-20th century, Barthes wrote essays exploring his day’s emerging cultural myths—later collected and translated in the book Mythologies. Fifteen critics share their takes on some of the famous theorist’s original topics.

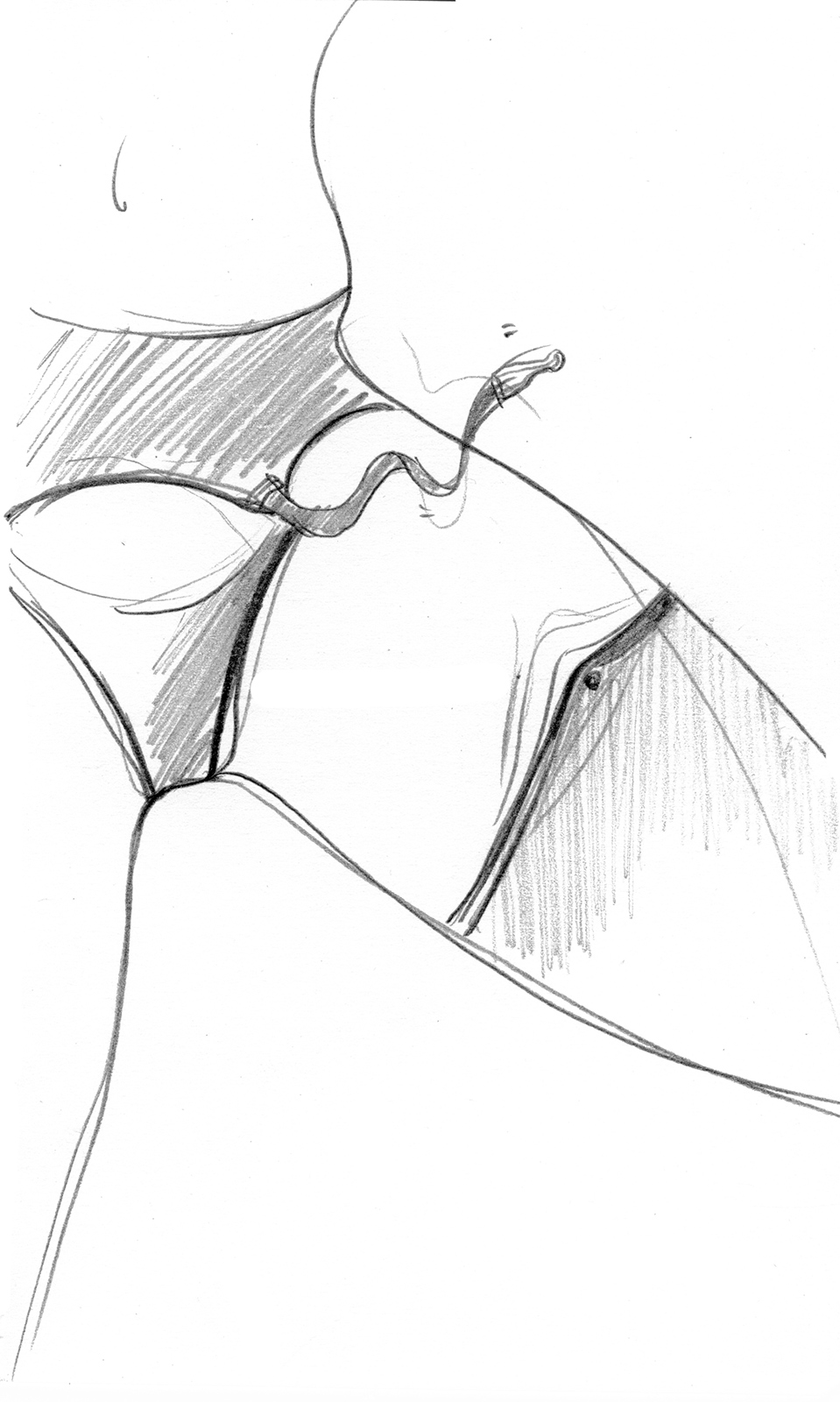

Striptease

by Journey Streams

Public life is a peepshow. No longer confined to sleazy venues and hungry eyes, the striptease begins anew wherever the apparatus of object permanence falters. Her dress is a billboard, interminably concealing a history of forgotten wantings. She who wishes to be known is implicated in this spectacle à la carte, corroborating for herself that which no one else can see. An innermost essence must prove its own presence.

Conversations sutured by vague answers to vague questions outline the cadence of her movement. Her memories are specious. Her appeal is unspecified. Still, a feather tickles a shoulder and her particularity crystallizes into an object itself; a tantalizing glimpse at some deeper, unreachable truth. The garment is unfastened, but pursed against her body.

Through this piecemeal revelation, she feigns a wish to remain concealed in spite of an erotic certainty: She feels most herself when she is naked. Though even as pure flesh, with all signifiers and caveats peeled from her body, there still remain several hundred other membranes concealing something more vulgar. Her allure affirms that we can only have what we can’t want. A strap slips; eye contact. The fantasy is already only yours.

As the layers fall from her figure, the anxiety inscribed in her gesture is less concerned with the exposed body’s unrealized seduction potential, and more with the possibility that, beneath it all, resides a blemish that betrays a fantasy—or an oblivion. At a certain point, the mystique disintegrates. A garter belt hits the floor and her audience is delirious, driven by a feeling without context toward an impossible threshold. She appears decipherable, but she is no more naked than she was before. The desire circuit remains unbroken; nipple pasties are a last resort.

Conjugals

by Taylore Scarabelli

One of America’s foremost representations of modern marriage is a reality television series that follows lonely citizens as they attempt to import life partners from overseas. On TLC’s 90 Day Fiancé, would-be spouses are byproducts of globalization: affordable goods that promise to make their consumers feel beautiful and wanted and seen. For the imported, marriage provides a different type of safety net, one that offers a gateway to working permits and the American dream. Though symbiotic in theory, these relationships are often so culturally, physically, and economically mismatched that fairy-tale endings rarely result. Instead, the network offers drama-fueled spin-offs like Happily Ever After?, in which the emotional and financial toll of immigration-driven marriages appeals to a predominantly American audience whose chaotic corn-fed relationships seem like romcoms by comparison. I remember first watching the series during an extended stay in New York, roughly eight years ago. My roommate and I would laugh at the besotted couples, greedily seeking pleasure in their desperation for partnership and its perks. Soon after, I fell obsessively in love with a Russian immigrant. We married within months, and a year later, my very own green card arrived in the mail. Sometimes I make my husband watch 90 Day Fiancé with me. He doesn’t find it funny.

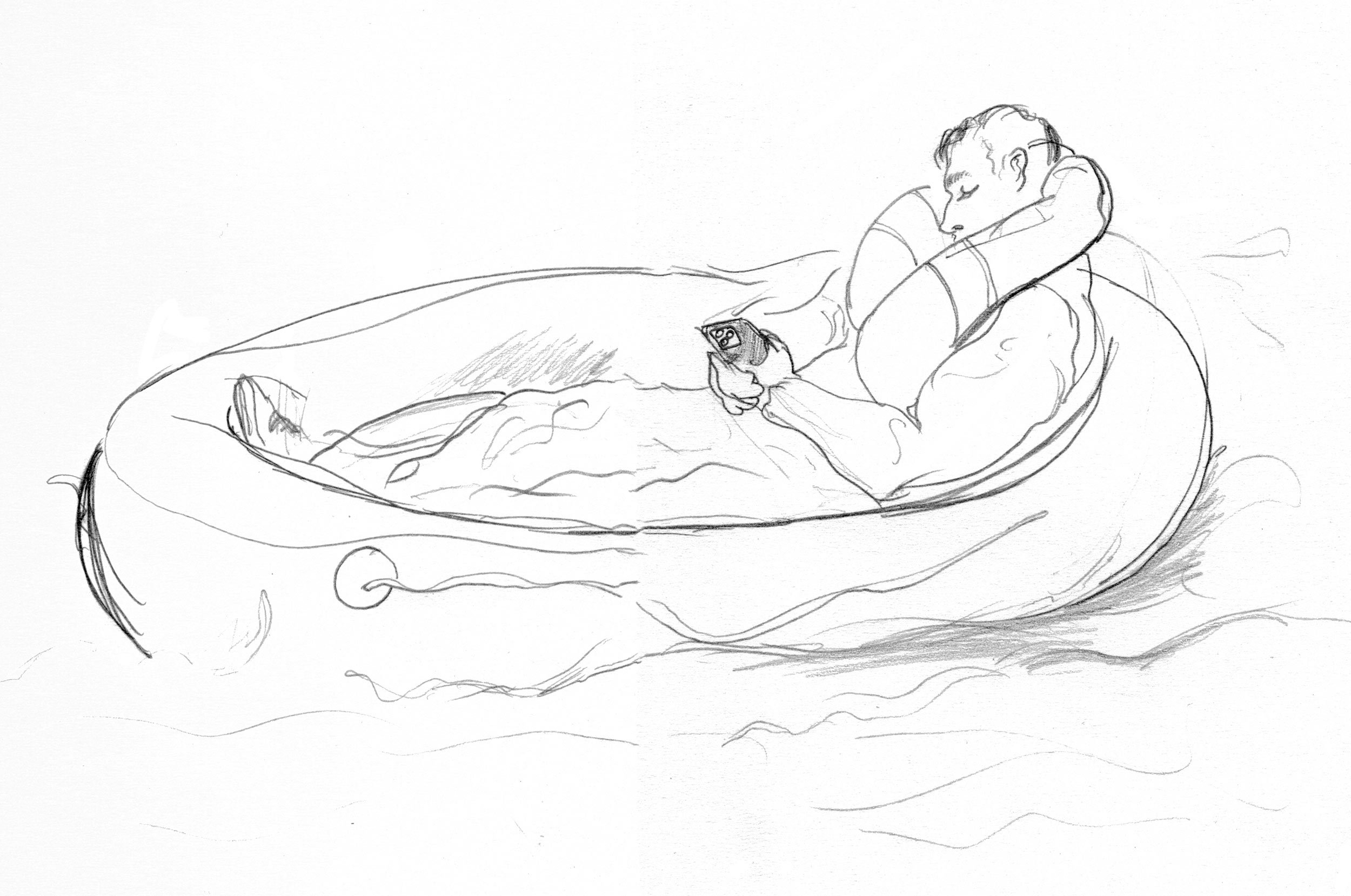

The “Blue Blood” Cruise

by Philippa Snow

In January 2024, the nine-month-long Royal Caribbean Ultimate World Cruise became the latest bit of anecdotal blah with which the international press made its readers drunk, by virtue of it seemingly being attended almost exclusively by TikTok and Instagram influencers. The ship, which is currently freighting all those influencers between 60 countries, has immobilized and gathered them, constituting a temporary reservation where these social curiosities can be kept and, perhaps, studied. This situation, which is as Ballardian as it is Barthian, is divine in its ridiculousness, even if watching it unfold does not feel quite right from an ethical perspective (especially given that the cost of the cruise, for those paying, can run up to $100,000). The influencer’s job—to wear for a fortnight, or for one night, clothes from a cheap chain store, and then discard them into landfill—is full-time, somewhat opaque to those who are not part of their milieu, and suggestive of the possibility of an almost total democratization of both wealth and fame, even if this democratization is entirely theoretical. What are influencers if not ordinary civilians who, via a combination of technology and (questionable) artistry, temporarily borrow a superhuman essence—milkmaids playing at being Marie Antoinette? They’re the new royals, self-obsessed and selfappointed. On camera, they have learned to exude a heightened ultra-realness, and the neutral gestures of their daily lives take on an exorbitantly bold character; rather than being rare beasts, characterized by their membership of a select and ordained breed, it is the purported everydayness of the influencer that makes them, paradoxically and somewhat amusingly, into a kind of secular demigod. Their sacrifice of sanity determines and externalizes the signs of daily bliss, saying that what achievement looks like is being paid to spend nine months on a boat with other people who are being paid to spend nine months on a boat; being teased with the chance of seeing one or more penguins at a distance; eating from a buffet every day, for a length of time equivalent to the full gestational span of a human being; being given the opportunity to see the world, even as one is being seen by the world.

Depth Advertising

by Natasha Stagg

We have reached a time when a simulated face created by artificial intelligence, an artistry superior to the human apparatus, is impossible to distinguish as a non-likeness. It is unlike any person in particular, but it is similar enough to persons we recognize as real, and so it is canny. Meanwhile, close friends and acquaintances are representing themselves through filtered imagery as smoothened, stretched, chiseled, with childlike eyes or surreal additions to their bodies. They are less recognizable as real, even if they are very much persons with organs, pulses, breaths.

Then there is the ideal, that ultimate rarity from which these inclinations to modify are born: prepubescent skin on a post-pubescent being (features considered ultra-feminine or masculine or androgynous or healthy or disciplined or fertile or sun-kissed or clean or athletic or wealthy, each being subjective to factors such as era and demographic).

In advertising—and by that I mean all types of promotion, including individual self-depictions sent to potential mates—we find the fine line that is always being redrawn, a line that is based on what we see in other advertisements. Any look can oversaturate or regain relative obscurity and therefore be exciting (again).

Too smooth is too much; it looks artificial, inconsistent, dishonest. We know, of course, that too real is easily accomplished as well. (Beauty products prey on our dissatisfaction with the way we look in photographs, pushing us to “erase” our pores, and so we spackle those gaps with primer wax, essentially a sanitized version of the grease that made them so large in the first place.) Then there is the scam: too good to be true, a vixen reaching out to an outcast with pure intentions.

But another category, the so-real-it-might-be-fake, something so convenient we cannot trust there is even a person behind the image, is a newer phenomenon, one that will no doubt affect the ebbs of commercials and the skincare/makeup industries. How deep does the image go? How many pores are too many, making a face so convincing it feels like a threat?

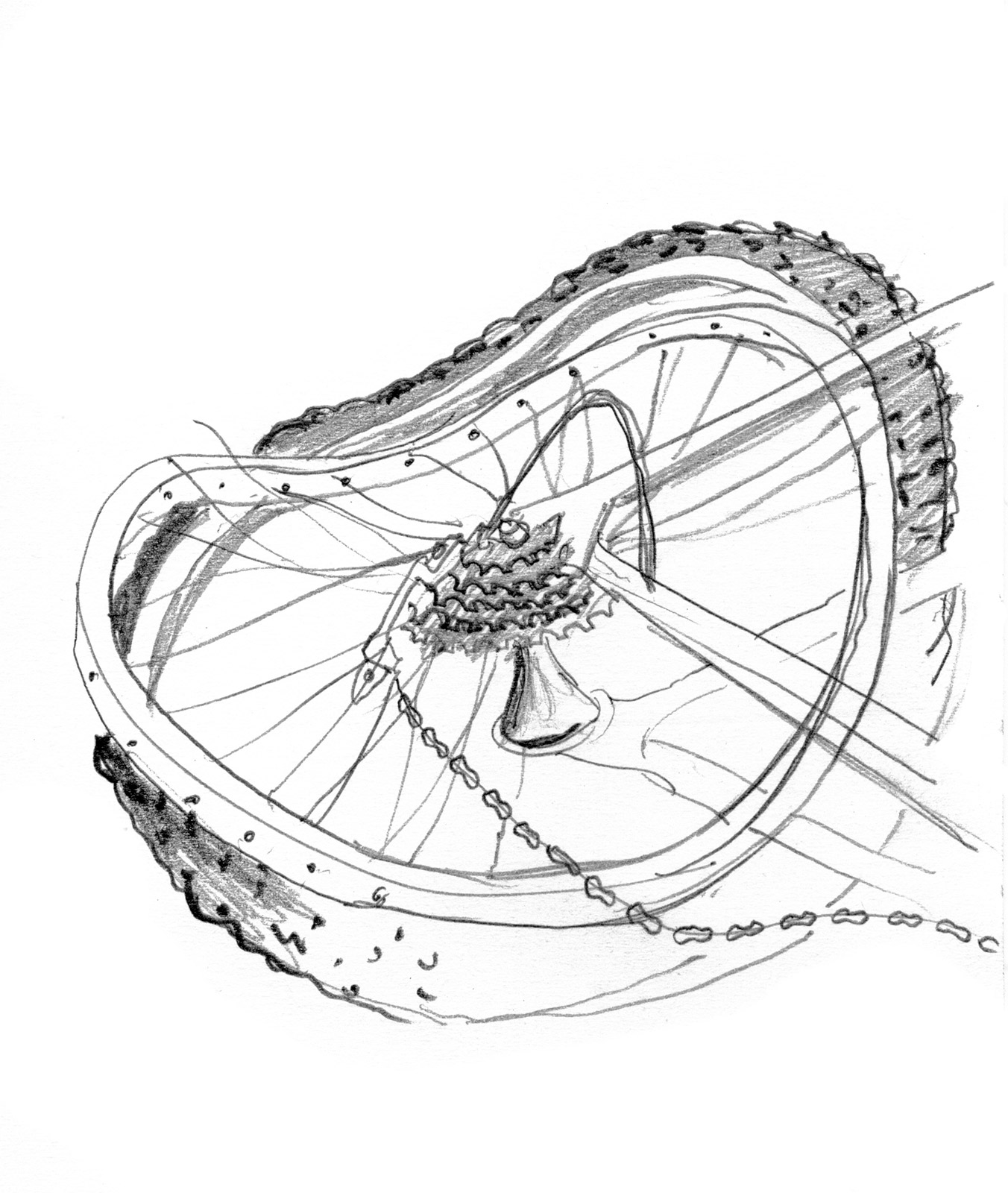

The Tour de France as Epic

by Maya Kotomori

Athletic competition is war. It implies a fight where the winner is not so much vindicated by their success but by the defeat of the other. When competing with others, the opponent is an identifiable assailant; when competing with yourself, the vanquished other is a foe from within. When you crush it, you squish the little thing in you that can’t, won’t, or doesn’t believe in itself. Victory is the ultimate reward, and you have to kill just a teensy part of yourself to get it.

Competition in professional cycling is suicide. There are infinite ways you can kill yourself on a bicycle. That is the spectacle of the Tour de France; not the bizarre glory achieved by shooting through the final bend of the Champs-Élysées, but the pageantry of risking life and limb, hurdling at speeds between 25 and 40 miles per hour (up to 75 when going downhill), balanced on two wheels the width of a cha-cha heel. What does it say about this sporting event that its winningest participant was excommunicated for blood doping? Lance Armstrong’s over-oxygenated blood cells were strong-arming the weak ones much like Peter Sagan did to Mark Cavendish in a famous 2017 crash. Armstrong lost the internal competition and is remembered stripped of his victory; Cavendish dislocated his shoulder in last year’s race in an understandable lapse of balance. Losing on two feet already sucks; failure on a bike adds injury to injury. Psychologically, egos bruise and dreams dash; physically, hands, knees, and shoulders are scraped to bloody pulp.

And aurally, the peloton’s unofficial soundtrack is from Kraftwerk. It feels a bit out of character for a group of German layabouts to take interest in a sporting event so physically involved, and then you remember that Kraftwerk cycles through its members like, well, a grueling high-stakes bike race. Shockingly, like the Tour de France, they’re still around, even after losing several members to mysterious disputes.

“What I wouldn’t give to be a medium-ugly Frenchman preening in high-vis spandex this July,” said no one ever. Or so I imagine—I’ve never learned to ride a bike.

Power and Cool

by Chris Kraus

Even though it came out in 2008, I think of Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah as the first movie of the 21st century. Adapted from Roberto Saviano’s great investigative book about the Neapolitan criminal cartel Camorra, the movie opens with a bloody massacre between two rival clans underneath the cheesy, ultraviolet lighting of a tanning salon. Debuting one year after the final episode of The Sopranos, there is no psychology behind the actions of anyone involved with the Camorra. Fear and money are the only operating factors. The organization reaches everywhere—from housing projects to urban planning to haute couture, where garment factory owners are forced to underbid each other. It’s a world of too many people, too few resources. Boredom, scarcity, malaise, and casually expedient violence… like the Baudelaire line that prefaces Bolaño’s 2666: “An oasis of horror in a desert of boredom.” As Saviano wrote about the film: “We forget what Gomorrah really is. Gomorrah is not a mere synonym with Camorra, Gomorrah is an economic system wherein everything is missing, where there are no investments, no opportunities, no education, no jobs, no resources.”

Wine and Milk

by Paige K. Bradley

Milk is the sort of beverage I pour for myself when I’m alone and want to take the edge off. Dairy, oat, soy, almond—I don’t discriminate. I’m not such a delicate flower that I concern myself with inadvertent hormonal boosts or deficiencies. I have bigger fish to fry.

Wine—I started drinking it in my early 30s (which was years ago, mind you). Often with a piece of broiled salmon since the dish is straightforward enough, and a small flank of it from Whole Foods these days is somehow more affordable than nearly anything else I can imagine preparing for dinner. Thank you, fuck you, Amazon.

In Mythologies, Roland Barthes said “wine supports a varied mythology which does not trouble about contradictions.”

The other night, I pitter-pattered into the kitchen to finish off some 2021 Xinomavro, a Greek red, which my guy had left behind in the fridge for me before he shipped himself out to the West Coast (and, by happenstance, also met one of those Greek shipping heirs). I stayed behind because my self-assigned workload these days can hardly justify a party junket, even to my place of origin.

Slipping up, I pour a glass of milk instead. I stare at it—would I be in for some unpleasant business if I were to have both, then? There’s no one to turn to, especially when you like neither phone calls nor asking Reddit and have zilch in the way of ancestral knowledge. I down the 2 percent and segue to polishing off the vino while marinating the main course—me—in the bath. Slipping into the mind palace wherein I have enough room in this porcelain bucket to actually unfold myself, I reflect on another bit of Barthes: “Wine has at its disposal apparently plastic powers: it can serve as an alibi to dream as well as reality, it depends on the users of the myth.”

An unwelcome gush is more or less all I dream about using milk for. It has a downward momentum, to my mind. I suppose I don’t really respect it, and even if I need it from time to time, it doesn’t hold my interest. Wine has an air of intrigue about it, since we can play word games with it—oh, this one has a tinge of grapefruit, that one’s gravel, and so on. I would say it has an upward swing—ideal for suggestions, propositions, and the like. With each direction swallowed, I felt appropriately neutralized—goodnight moon!

Plastic

by Camille Sojit Pejcha

It’s hard to think of anything more optimistic, or misguided, than plastic. When the first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, was introduced to the public in 1909, it was marketed as “the material of a thousand uses”: a miracle substance that could forge lighter, better, stronger, and (most importantly) cheaper versions of pretty much everything democratizing and duping coveted goods like amber, tortoiseshell, horn, ivory, and, as German scientists discovered in 2017, even diamonds. The problem is that plastic, too, is forever. Over 100 years after its popular adoption, this magical material has worked its way into not only every aspect of human culture but also the human body itself. Tiny particles of microplastic have been found in our lungs, our blood, our shit, our breastmilk, and our placentas.

When plastic took the place of elephant ivory, it was hailed as a savior of the natural world, an antidote to our greed, and a symbol of infinite possibility. But the egalitarian dream of plastic, like the 20th century’s American dream, has been debunked. Today, “plastic” is a synonym for that which is flimsy, fake, superficial, and false. It is, as Barthes wrote, “the very idea of its infinite transformation”—and true to its nature, plastic took on the properties of the society that shaped it.

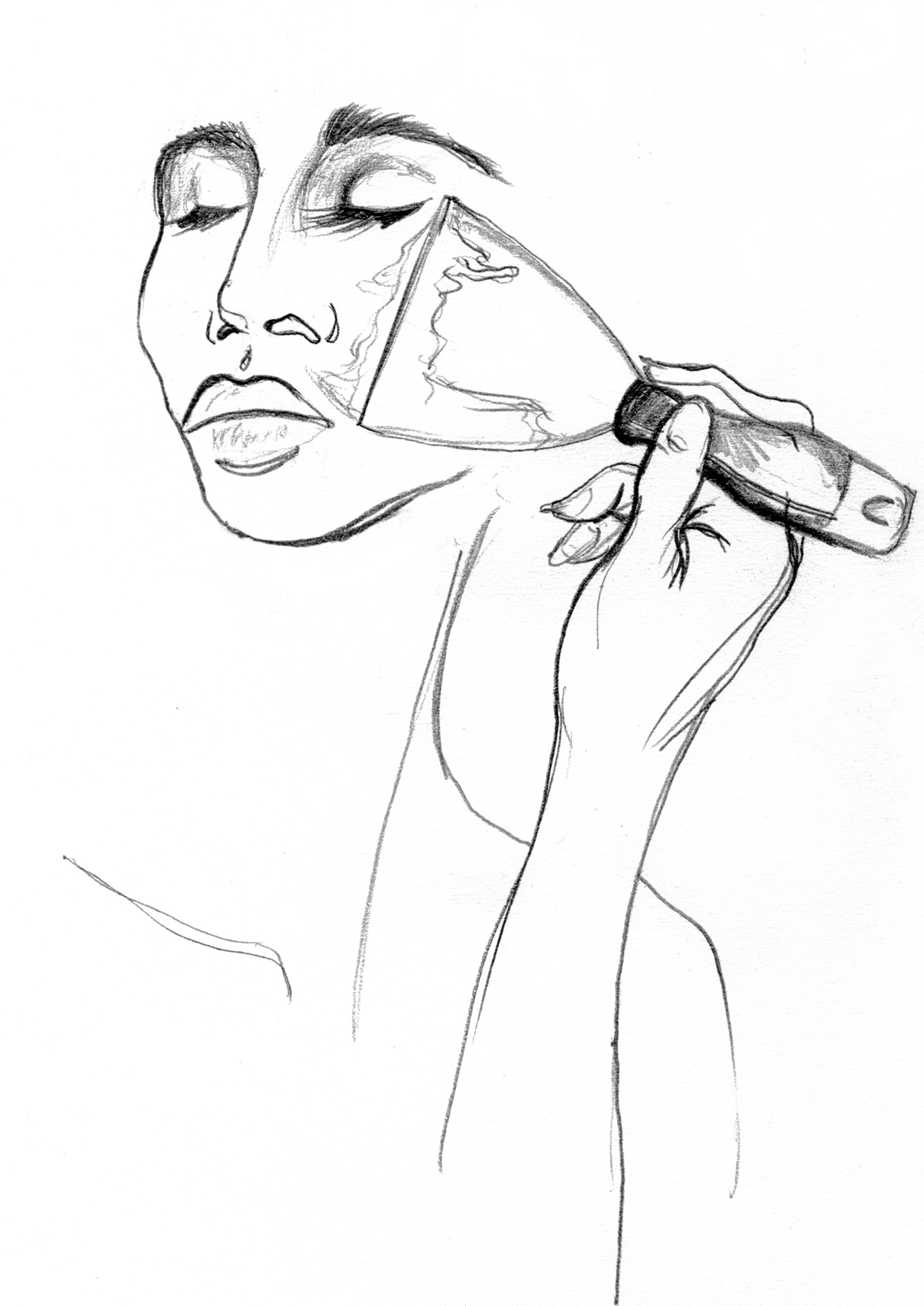

Garbo’s Face

by Jamie Hood

Fame doesn’t turn me on. I bartend for famous people all the time. Mostly I don’t recognize them, an inattention I’ve been told they take as a relief. Really, I feel bad for celebrities, because for them, there’s no getting outside the spectacle anymore, and because today’s celebrity culture is so inert, and so sexless, and sells nothing but artificial youth and its own protracted death, somehow simultaneously. The fact that there’s no actor you could write “Garbo’s Face” about now signals a profound diminution in the world, and I wonder if we’ve suitably grieved this stinging loss of beauty, or our capacity to encounter it—the sort of beauty, as Barthes cites in reference to Rudolph Valentino, that perturbs, that might drive its witness to suicide, and arrives as in a kind of marble, the sort of beauty that promises eternal damnation. (I got my face done last year, and my tits, so don’t take this to mean I’m applying for membership among the growing ranks of Literary Women Against Cosmetic Intervention. Besides, I’m no Garbo and, anyhow, I’m not retiring from public life if I can help it.)

Maybe it’s that everyone’s famous now so no one is, or that 20 years ago, Facebook convinced the zittiest boy in your physics class he could call Angelina Jolie “mid”; maybe it’s just that everything’s gone flat, that our field of vision has been rendered uninterruptible, or that all the world is ugly now anyway. Every day we witness the immensity of this ugliness, we become convinced we must abide the cruelty and violence and exploitation that make our largely tedious lives possible. None of us have faith in the likelihood of our damnation any longer. The only god I hear spoken of now sounds like Ricky Gervais on a fake cross; he doesn’t matter. Hell is just another day on Twitter. Hell is an hour on a stalled train. Hell is no longer an idea; it is a dull procession of events.

Ornamental Cuisine

by Rayne Fisher-Quann

The LCD light looks delicious today, and thank god—we’ve all been so hungry. The figs are fleshy and furled like babies’ fists, desiccated and sparkling in their own sugar. Anchovies swim in olive oil and aqueous cheeses. There are beans—big ones, brothy. Everything is lactic. A thick, textured sauce poured over pickled fish dares me to find it unappetizing, to expose how little I understand about the tastebuds of the cultural upper class. All the most beautiful people are eating translucence: jellied vegetables, candied fruits, a pearl onion, a poached pear, a steamed cabbage leaf, a perfectly jammy egg yolk, an elastic sheen of raw fish. The ceramic tableware that holds it all is kitschy and expensive. The vegetables are always in season. I heard someone say once that the feeling of “grotesque” is borne from friction between the natural and the unnatural, the tension between the living and the un-living; I scroll past a fish head encased in gelatin, a cow’s tongue pickled and preserved, a too-red maraschino cherry.

Scroll to somewhere slightly different and a candy-colored cake will be presented for your consumption, decorated in eddies of thick, calcified icing, styled in an aesthetic pastiche of the ’50s or the ’60s or whichever decade it was when they drank milkshakes from double straws and the boundaries of women’s labor were strictly and comfortably defined. Cake masquerades as inanimate object; class nostalgia masquerades as cake.

I’m scrolling again, looking at a sandwich that’s inedible in one sense because it’s stuffed so full of ingredients that I’d never be able to fit it in my mouth, and inedible in another sense because it only exists on my screen. This food, in this form, is never eaten—it is immortalized, almost always, in a state of pre-consumptive perfection—but it is also eaten over and over and over again, consumed and digested by eyes instead of stomachs. At last, you can have your cake and eat it too—you can eat it until the blue light burns a hole in your corneas. What were you hungry for, again?

Myth Today

by Trevor Paglen

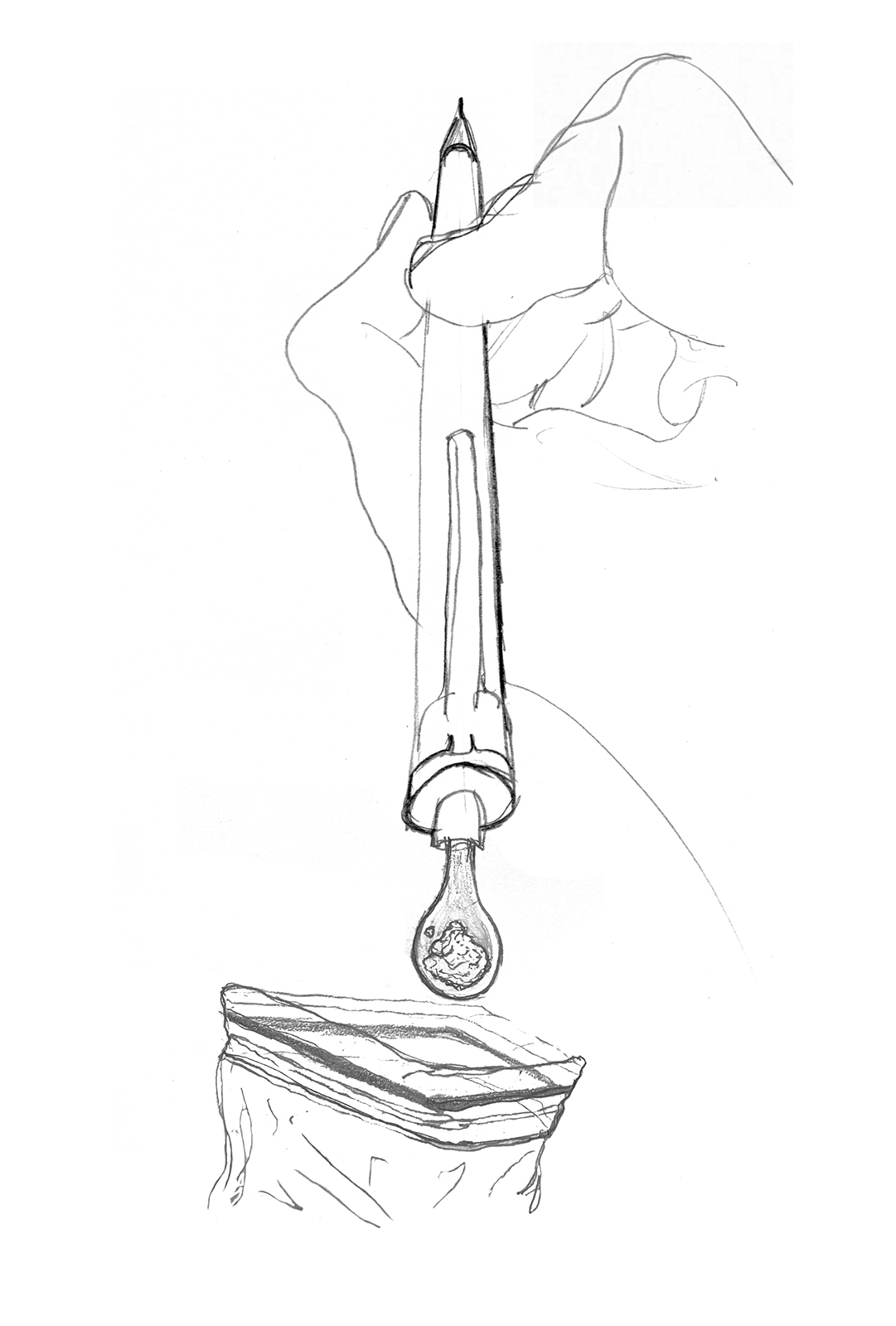

In the concluding essay of Roland Barthes’s Mythologies, titled “Myth Today,” he attempts to theorize the anatomy of mythological images using a framework largely borrowed from Ferdinand de Saussure (for Barthes, visual signifiers and language are somewhat interchangeable). For the French semiotician, myth is a cultural form of conservative politics, the defining feature of which is to depoliticize and naturalize history and power relations in order to make it seem as if the status quo were eternal and innate, rather than contingent and political. At one point in the essay, Barthes reveals his suspicion that there might be a deeper problem: that any linguistic system based on signification, representation, and mediation might have myth-making as a feature rather than a bug. If that were indeed true, could we imagine a different form of language? One that was somehow structurally incapable of producing myths?

In a famous passage, Barthes invokes the image of a woodcutter, writing that “if I am a woodcutter […] I ‘speak the tree,’ I do not speak about it.” In other words, the woodcutter’s language vis-à-vis the tree is “operational” and “transitively linked to its object.” For Barthes, this “operational” relationship between the “speaker” and “object” is defined by action, not representation or mediation. In this transitive vernacular, Barthes sees a glimpse of what a revolutionary language of liberation might look like.

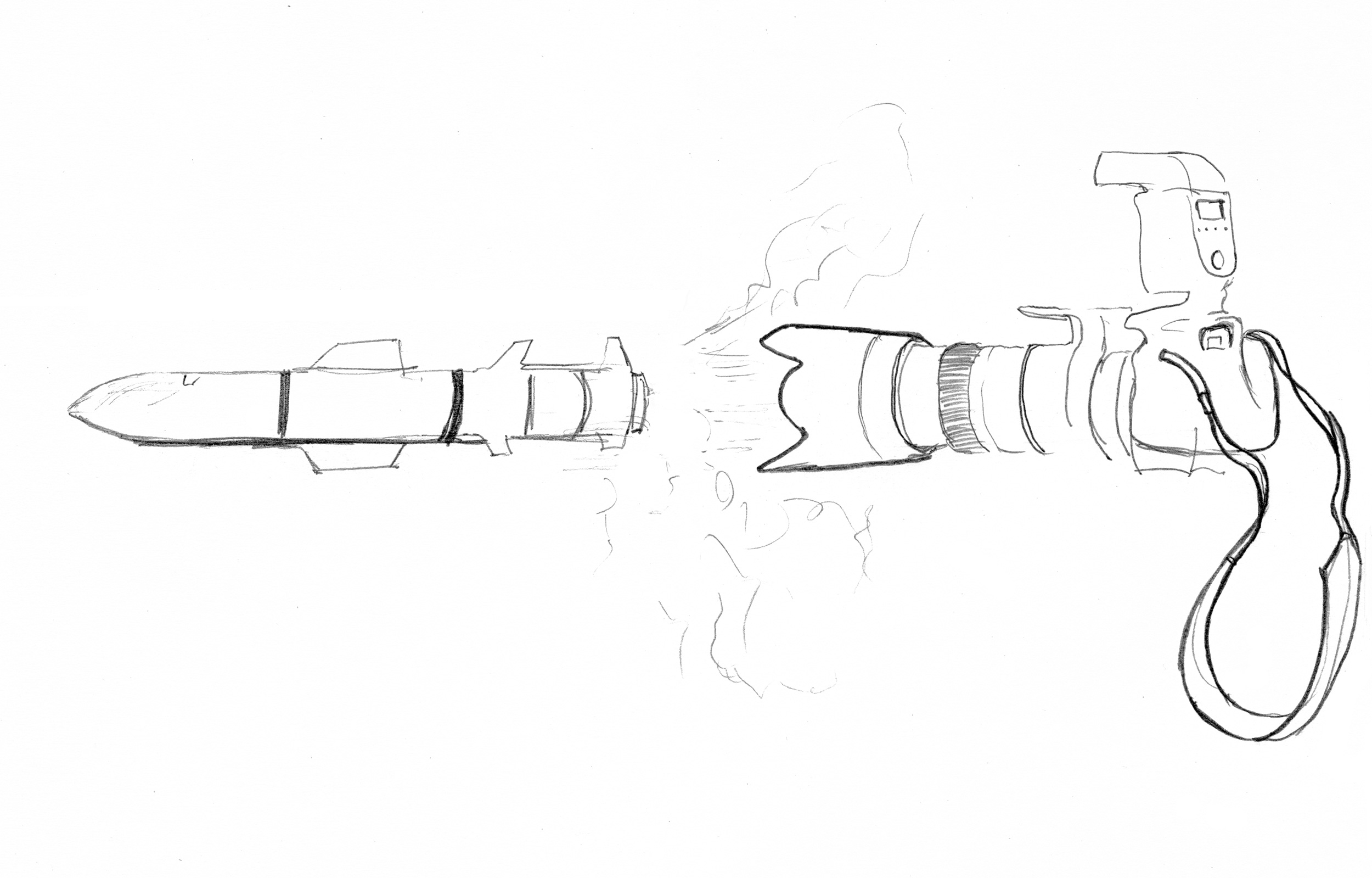

The filmmaker Harun Farocki takes up Barthes’s notion of transitive language in his examination of what he called “operational images”: images that are part of a circuit of action, such as images used in missile guidance, smart bombs, surveillance, and targeting. Farocki suggests that there are indeed images that are not “mythological” in the sense that they’re part of an action, but that this transitive property of images doesn’t guarantee that they point to a politics of liberation (they may do quite the opposite).

The contemporary media landscape—one that is increasingly characterized by a merger of the operational and mythological image—is one Barthes may not have believed to be possible. The algorithmically guided images and media we see on social media and the web are designed to induce a reaction as much as a representation. Think of the salient emotions these types of media are tuned to invoke in us: fear, outrage, etc. With the emergence of generative AI, images and media that are both mythological (“Look what the woke mob is doing!”) and operational (“You are angry!”) will be ever more finely tuned to elicit specific emotional and affective reactions based on each of our metadata profiles.

In short, in an age of increasingly “operational” images, myth is not only far from dead, but, ironically, the transitive properties of images may do more to amplify the salience of reactionary politics than dispel them.

The New Citroën

by Drew Zeiba

When Citroën released its C4 Cactus in 2014, US outlet Car and Driver published a review subtitled “Jean-Paul Sartre, your car is ready.” Sartre serves as shorthand for France’s apparently atmospheric philosophical rigor, contra the mental lassitude of the anglophone petty bourgeois. From this “dek,” as we call the subtitles in the trade, one gathers that Car and Driver’s editors assume their readers have a glancing knowledge of philosophy, so long as it dates back half a century, or, if not, being able to think, “‘Jean-Paul’ sounds pretty French.”

Apart from a Mandela-effect situation—wherein some people believe, with no proof other than an English-original text whose authenticity likewise has no proof, that Sartre, a lifelong anti-imperialist, drove a Dodge Dart—the philosopher’s only connection to automobiles I know of is a connection in name only: the Safe Road Trains for the Environment (SARTRE) project, a European Commission-funded—though primarily Swedish and Spanish endeavor—to engineer electronically inked car platoons.

As for this compact crossover SUV’s Gallic themes, the C and D critic concludes: “Like raw-milk cheese, the Cactus will never come to the States, but it’s something you should be able to talk about at dinner parties. Pretentiously, of course.” (We all have word counts to meet. Working writers of the world unite!)

Nothing should disillusion Anglo-Americans from their pretensions about purported French intellectualism than this 1,000-kilo diesel-powered pod. A drowsy, bug-eyed bubble, the C4 Cactus boasts all the athleticism of an out-of work linebacker. Thick black brackets line its middle headlights (who can say why the front has three sets of lamps), and shiny black glass stripes branch from the rear window, cutting perfectly useless four-inch ribbons over the rear buttresses. Goading the eyes like a proverbial train-wreck, across the four doors on either side stretch polyurethane “Airbumps,” puckered spans that, allegedly, prevent minor dings during city driving. The needles of this so-called cactus, I guess.

As is the case of the triple headlights, the Airbump is not functional in the sense of having an immediate physical use that couldn’t be better addressed otherwise. Rather, it is functional in effectuating a visual vernacular common to cars of all calibers, as well as running shoes, overly cladded “gentrifier apartment” façades, or electronics marketed towards gamers—a quasi-sci-fi aesthetic vocabulary which advertises its distinction not by being “high performance,” but through the baroque performance thereof— a functionless ornamentation not unlike C and D’s referring to “Citroën’s recent époque de malaise” in an appeal to Continental credibility.

But maybe I’m being too harsh. As another likely fabricated quote attributed to Sartre goes: “Only the guy who isn’t rowing has time to rock the boat.”

The Writer on Vacation

by Geoffrey Mak

While the optics of Instagram are coded as autofictional, it isn’t our generation’s hunger for authenticity that fuels the demand for influencers (we know they are a simulation) so much as a collective thirst for the visual representation of leisure at a moment when neoliberal capitalism has made everyone a total entrepreneur of the self. No image personifies this more than the writer on vacation. On Instagram, she could be in Paris or Mexico City discussing gender theory over oysters and cocaine, or she is at the barricades, out to abolish the police, prison system, the family, and the nation-state. That these images delight with a ping of the unexpected (she is simultaneously just like you and who you could never be) affirms, rather than refutes, the impossibility of its claim. There can be no writer on vacation because she is permanently at work. She is always thinking. She is always interesting. Because the writer’s practice uses the stuff of the everyday—words, thoughts—she has effectively converted her everyday into labor. Posts demanding a ceasefire now and photos of her lying topless on a bed in blue Wrangler jeans are all part of the job chronicled on a three-column grid. There is no “free time” for the writer. If all that can be documented is that which can be commodified, dreamspace remains the only site left where she is free. She dreams of the naked man in an apartment window overlooking the High Line at night. She dreams of the solar eclipse over the Texan desert. She dreams of the revolution.

Toys

by Skype Williams

I’ve been playing The Sims 2 since it was released in 2004. Twenty years later, there is still a large community of creators making “mods” (as they’re commonly known in the community) for it: Mods can enhance and distort the software so heavily that it can become a completely different game. Another difference of adult play: My family’s shitty Compaq couldn’t have handled the 50GB of mods I have now.

There’s a stigma attached to an adult interest in toys or children’s media beyond adolescence. Think of “Disney Adults” (voluntarily engaging in arrested development), Barbie connoisseurs (relative sophisticates), or Funko POP! collectors (somewhere in the middle of the development spectrum). But what The Sims players share with Disney Adults and their ilk, beyond their respective communities, is that now, as grownups, we can indulge in and afford things we never could as children.

In my current game of The Sims 2 (the version specification is significant for those in the know), there are taxes, social security funds, qualifications and certifications for different jobs, and a mayor who decides it all. My vision is economy based. It forces the characters to make hard decisions; it’s perhaps difficult to understand for an outsider, but these characters take on lives of their own. I allow them to make decisions that make sense for them as individuals, and it creates stakes for me, their omniscient creator.

Physical toys like Barbie are fixed objects, leaving room for projection—you don’t need Ken or a Dream House because you can use your imagination to create different lives for her and give her a personality. Because it’s so “interactive,” The Sims could be more limited; the seeming range of choices prevents you from seeing the choices you can’t make, and thus what you can bring from your own mind. But with mods, you’re breaking this product apart and putting it together into something else. Either way, it’s about what you bring to it.

In terms of play experience, there’s not a radical break between the physical object or the digital interface. However, playing The Sims is much more discreet than, say, collecting Barbies; you can do it with the same machine you binge watch or answer emails with. For those who don’t play The Sims, new possibilities for gameplay seem unimaginable. They are little Sims in their own right, locked in rooms without windows or doors, unable to conceive or even see how expansive this “toy” can be. As Simmers, we can understand this arrested development with an air of sophistication, but ultimately (and gleefully) end up somewhere in between.

Einstein’s Brain

by Bruce Benderson

There’s a certain irony in my writing about this text by Barthes that is related to the importance of time in Einstein’s 1905 special theory of relativity, which asserts that the rate at which time passes depends upon your frame of reference. This is an idea that can also represent, at least metaphorically, changes that have occurred within my own life. The many decades I’ve had to digest Barthes’s Mythologies (the initial discovery of which, in my 20s, struck me as a seminal, perhaps earth-shattering, event) have recast this philosopher—one of our most treasured semioticians—within a less profound frame of reference: that of the dandy. It’s a dramatic change in point of view that I perhaps should have not found so surprising, having recently read a separately published appendix accompanying French novelist and essayist Benoît Duteurtre’s controversial polemical essay against Pierre Boulez, Requiem pour une avant-garde, in which Duteurtre posited an iron-clad dichotomy between two aesthetic schools. One side of that dichotomy, which Duteurtre believes French artists and intellectuals have emphasized for more than a century, champions visual and aural harmony, an immersion in sensuality, playfulness, and a high regard for pleasure. This is in opposition to the agonized profundity of the German school, characterized by a pessimistic ontology, permanently unresolved emotional conflict, and expressionistic gestures of post-romantic agony. Barthes obviously belongs on the French side, but which of his qualities place him specifically in the subcategory of dandy? When he alights upon a wide variety of dazzling literary, philosophical, and media references, before bouncing teasingly away, does he ever delve beneath the surface of any of these ideas? Or am I dealing, instead—I wondered during this most recent reading—with a clever and quick-thinking “jack of all trades,” whose ludic dance hovers perpetually at the surface, necessitating a denial of all substance, taken even further by a portrayal of the surface itself as nothing more than a pattern of fake entangled significations imposed by systems of power? Barthes was a young man when he wrote the short essays in Mythologies, and perhaps still in the grips of that rebelliousness that makes iconoclasm so enjoyable. Rhetorically, he puts himself in a category of one, as the only mind that can “see through” the spectacle that is controlling the rest of us, and this “above-it-all” attitude is a common characteristic of the dandy. Unfortunately, such an approach proves inadequate when it comes to the subject of Einstein’s brain. Rather than dealing with the substance of his thought, Barthes shrinks the idea of Einstein into a paper-thin linguistic sign whose mediatic superficiality he can scornfully deride and indict for its reduction of all of existence to the simple formula E=mc². Barthes’s approach precludes dealing with any of the ramifications of Einstein’s Theories, which encompass not only events as life-changing as the atomic bomb but also later experiments debunking Einstein’s rejection of quantum theory. For Barthes the dandy, such historical and cultural objects can’t be accessed except through the violent deconstruction of their cultural signification—and if they exist, it is only in the myths we create about them.