For Document’s Spring/Summer 2024 issue, the public secret society and art collective mobilizes a campaign for returning land to Indigenous Americans

A banner promising more effective payroll solutions. Another promoting for-profit nursing school. A poster for Narcan training, and another for a Netflix original series, onto whose star someone’s sharpied a leaking pimple. You look back to your phone and scroll past the sixth near-identical meal replacement service ad of this half-hour commute to watch a poreless influencer hawk a new rice filtrate facial cream—it makes me more myself every day, he intones parasensically. The intercom garbles the name of your stop. You stumble out of the train, tripping up the stairs, each step of which glimmers with fluorescent vinyl platitudes which you learn, upon reaching the top, promote a new aluminum-free deodorant. The fresh air stinks. Overhead, billboards sell you underwear you’re already wearing, and wheatpastes bubble on green construction-shed doors, teasing you with direct-to-consumer 14-karat jewelry and a just-passed tour by one of your favorite bands. In your ear, NPR’s pleading for donations to support its election coverage, but when you raise your finger to turn down the volume, your headphones clatter onto the sidewalk, alighting upon the faded outlines of a “guerrilla” ad campaign an Italian fashion brand sprayed on the concrete six months before, which though not legal, was not described as vandalism.

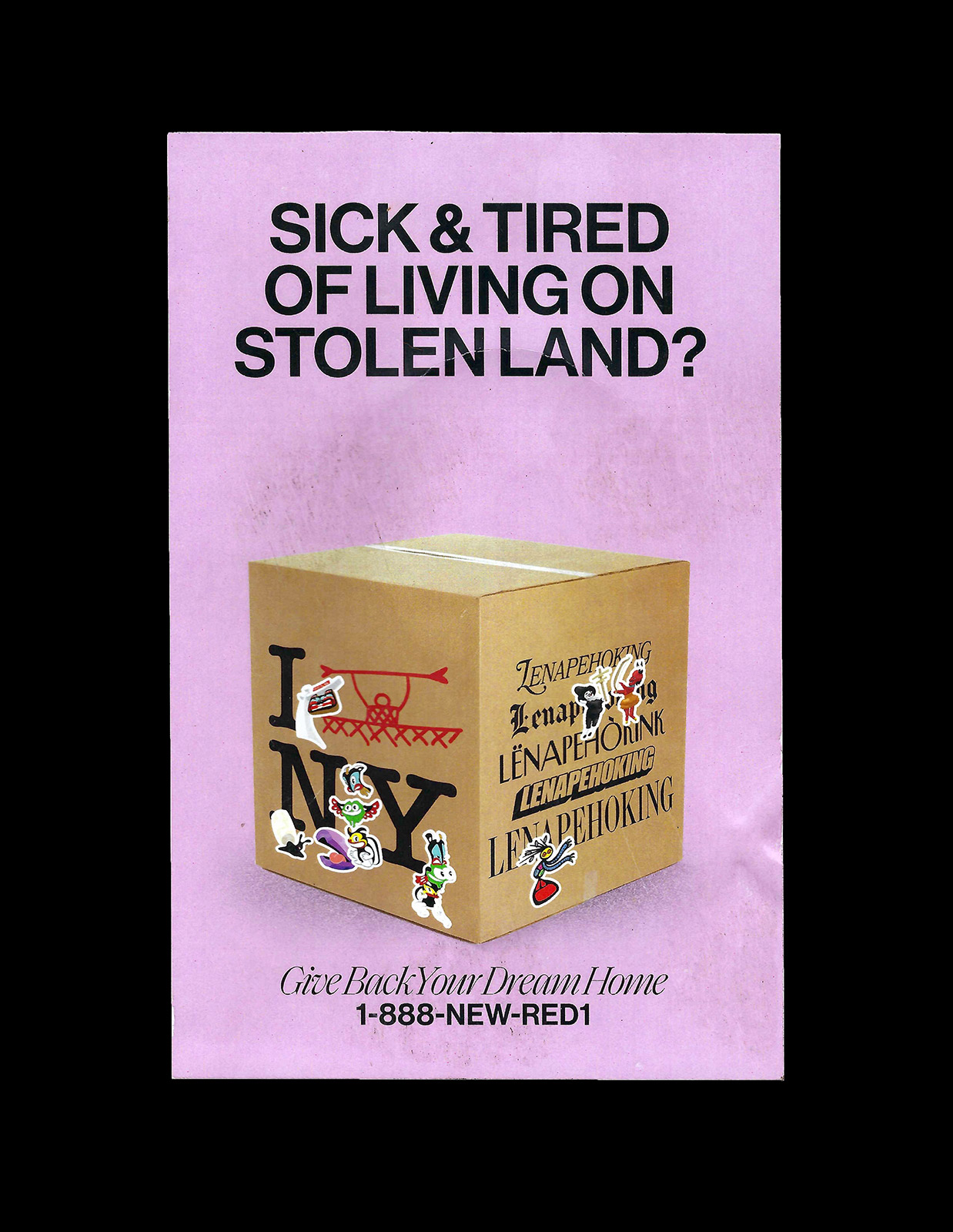

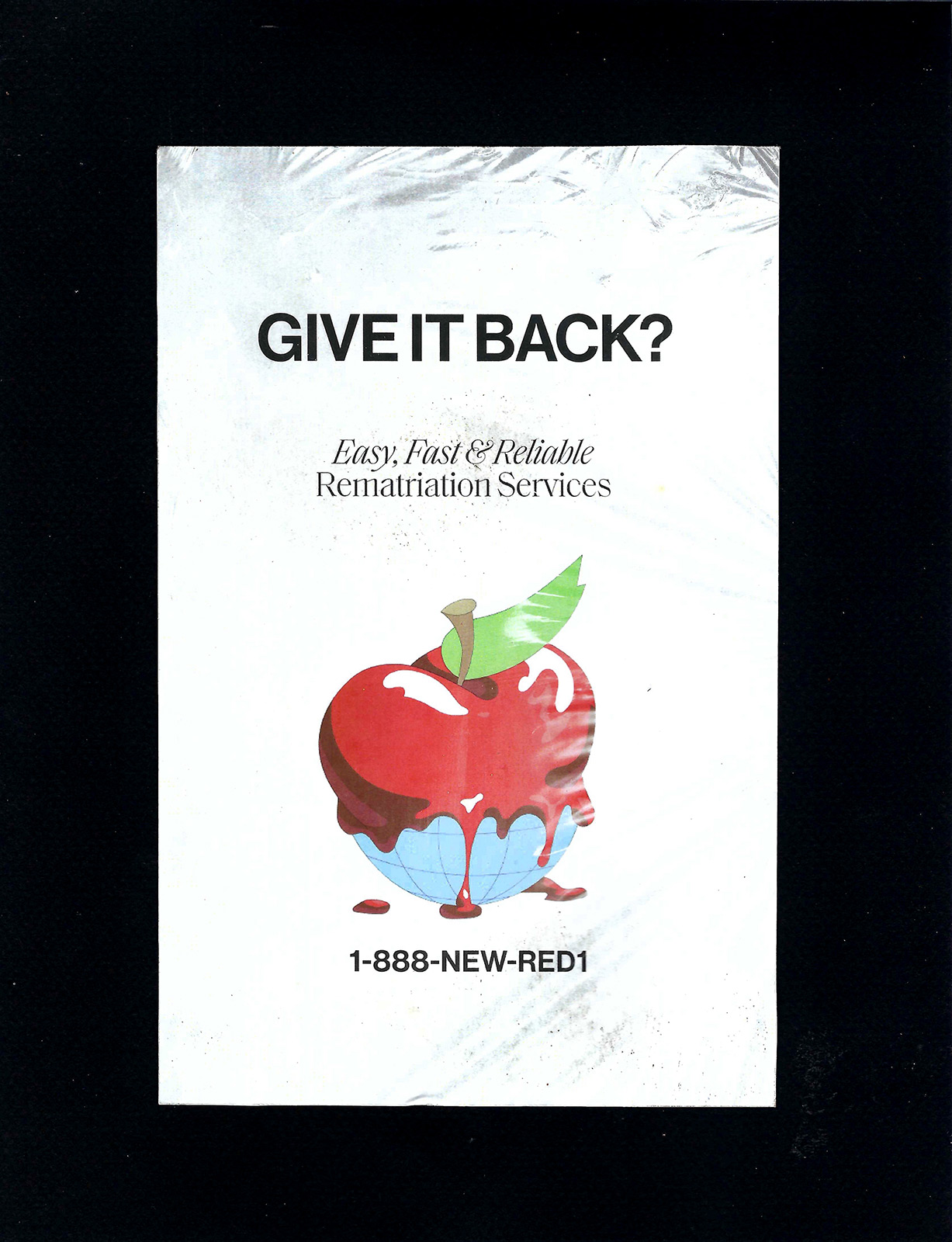

The agitprop of capitalism is everywhere—invisible in its unrelenting visibility—patterning landscapes of cynical symbology captioned by focus-group-tested typefaces whose serifs sprout revised baroque appendages each week. You barely notice—was it ever any different? You think briefly of a post you saw that claimed medieval Europeans only saw, like, three images in their entire life and wonder if that’s why you and all your friends are perpetually begging the few actual ADHD sufferers you know for their surplus Adderall. You decide the fact sounds fake. You decide this—this city of images—is fine. You decide you feel as if your stomach is distending, threatening to prolapse through some orifice you didn’t even know you had, and deduce this might be the start of a panic attack. You remember your mindfulness teletherapy session from earlier that week: Mentally list one thing you taste, two things you smell, three you see, Jessica, LCSW, advised over FaceTime. Spit, piss, Le Labo, smog, glass, and, of course, another ad, bright pink and with an image of a sticker-covered box—selling what, you’re not sure. “SICK & TIRED OF LIVING ON STOLEN LAND?” it asks, reminding you of a self-improvement slogan you’d read on X earlier that day, though this one seems a bit off.

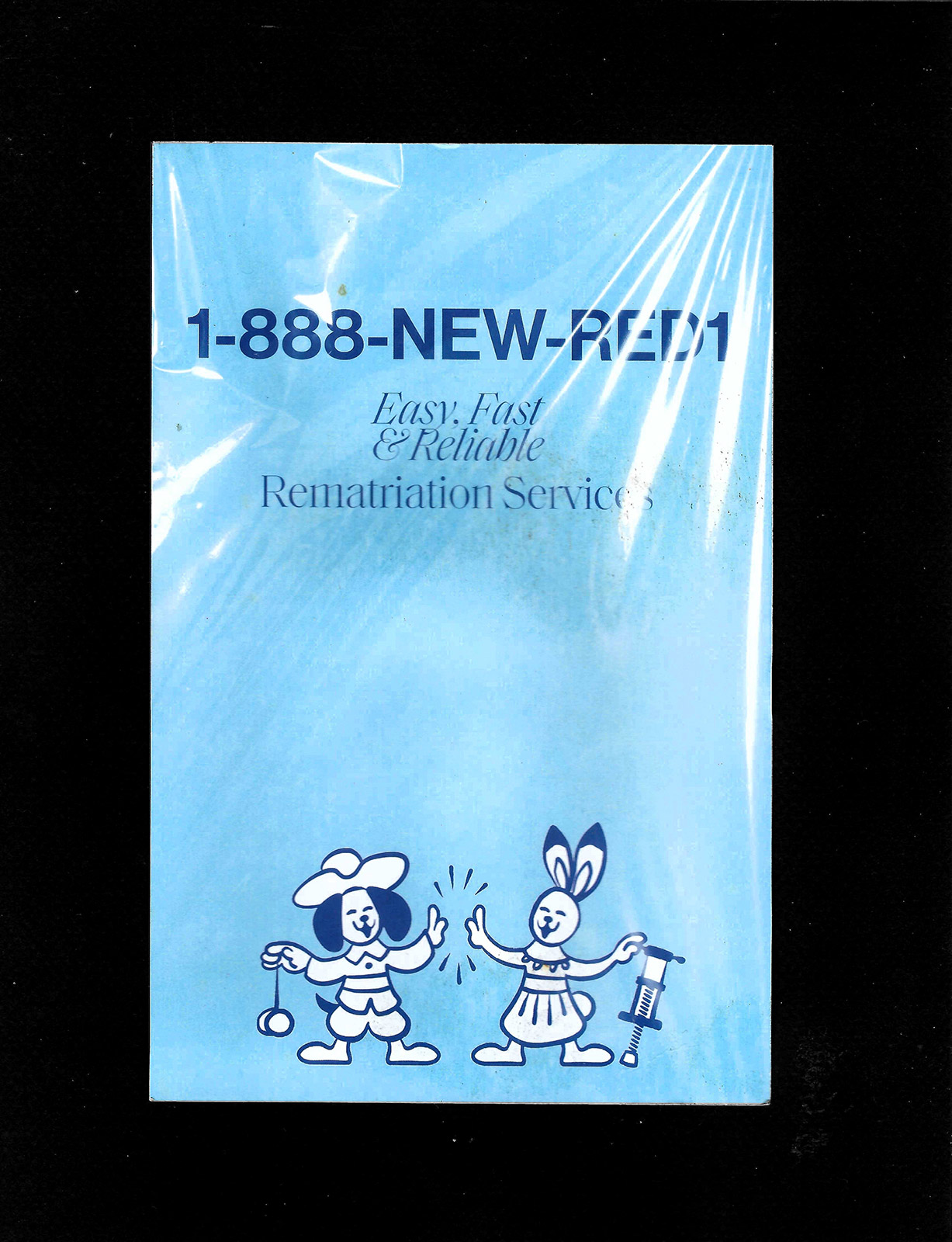

A 1-888 number lines the poster’s bottom. How retro, you think. Jessica says that to get over your anxiety around calling the insurance company, 311, a maître d’, etc., you should practice with less consequential conversations. You dial. Pan-flute elevator music peals. “Hello! Thank you for calling the hotline at New Red Order or NRO for short… We’re so excited for your call!” The Muzak turns more upbeat, possibly calypso. “New Red Order is a public secret society dedicated to expanding Indigenous agency and achieving decolonization, which brings about the repatriation of all Indigenous land—and life.” Air horn.

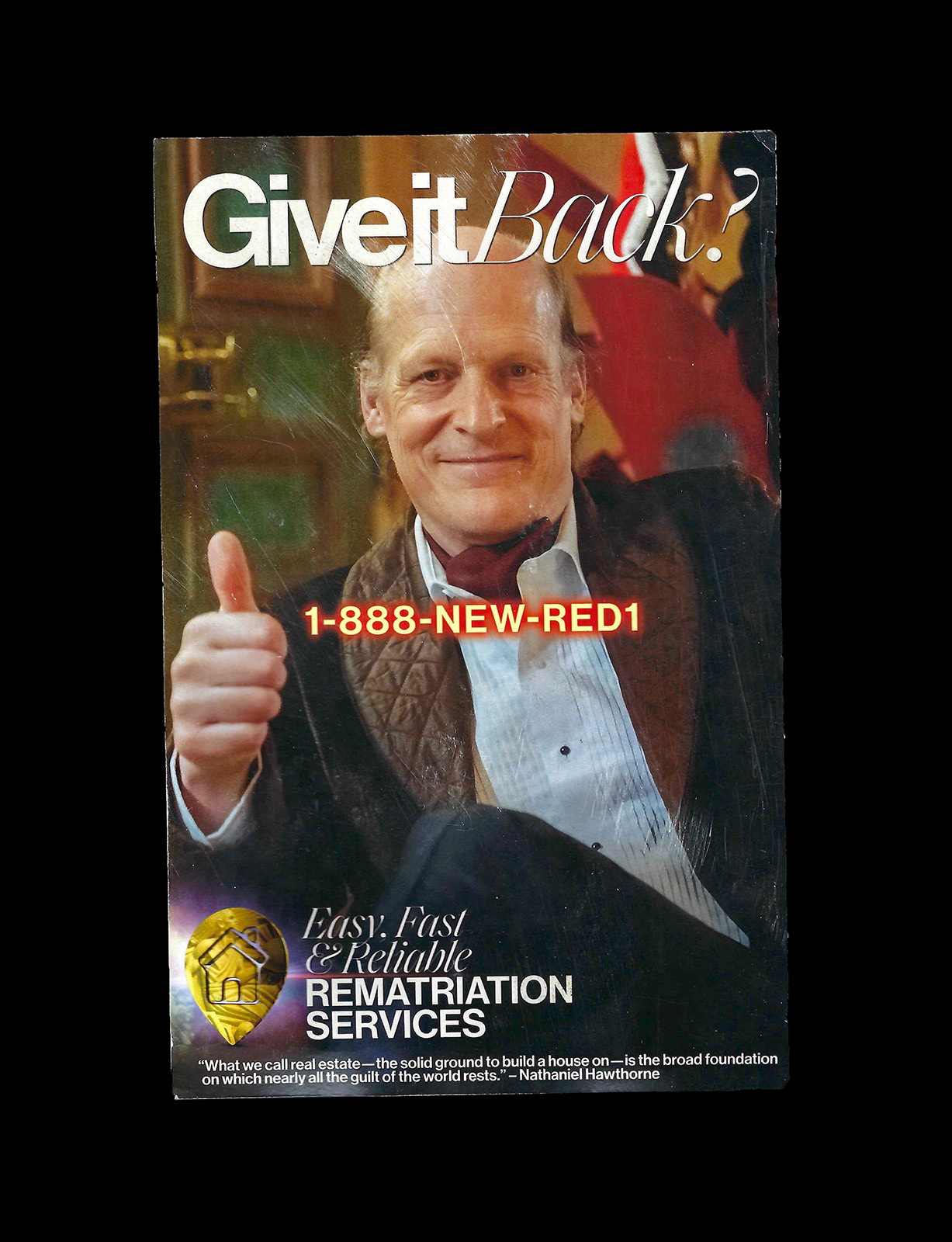

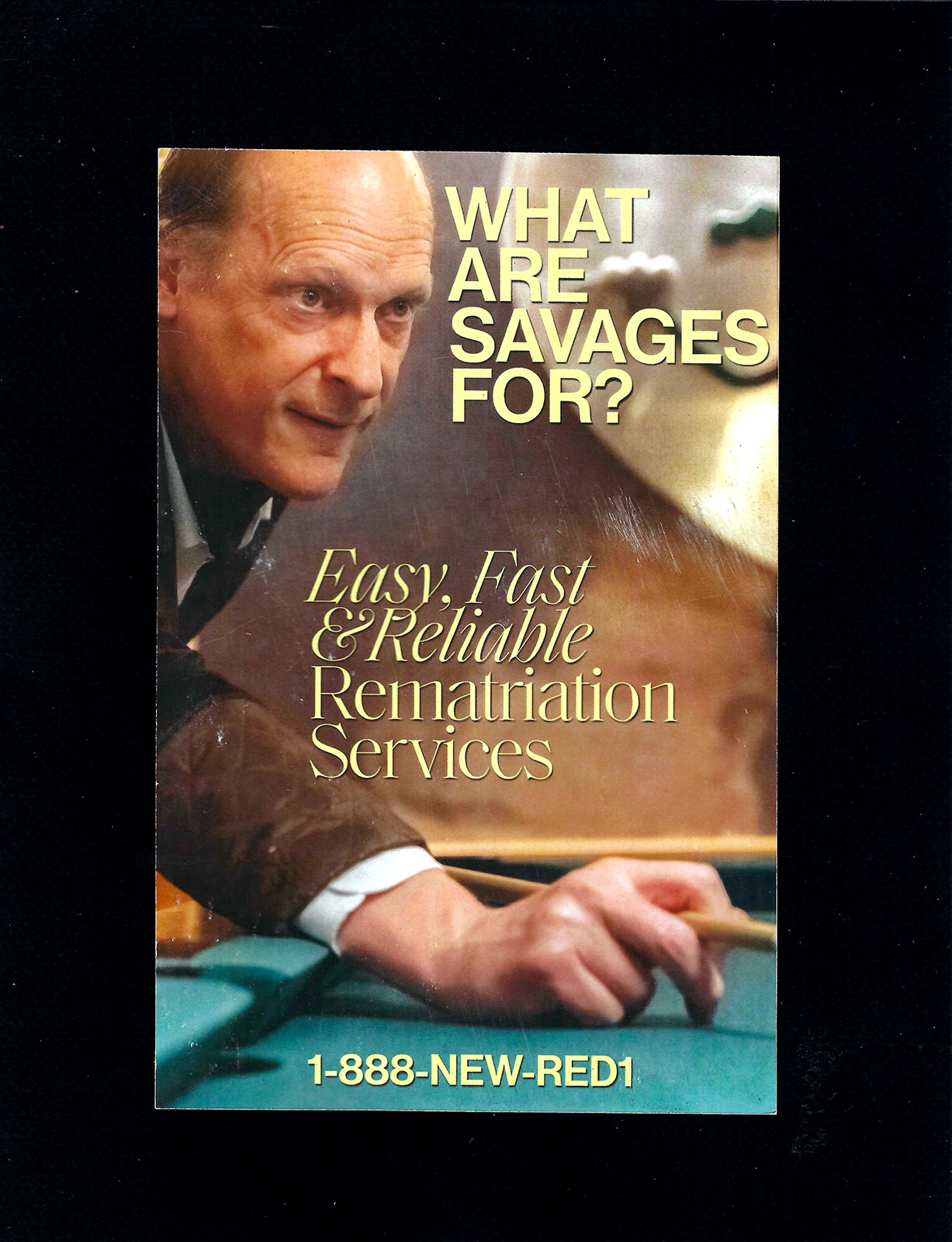

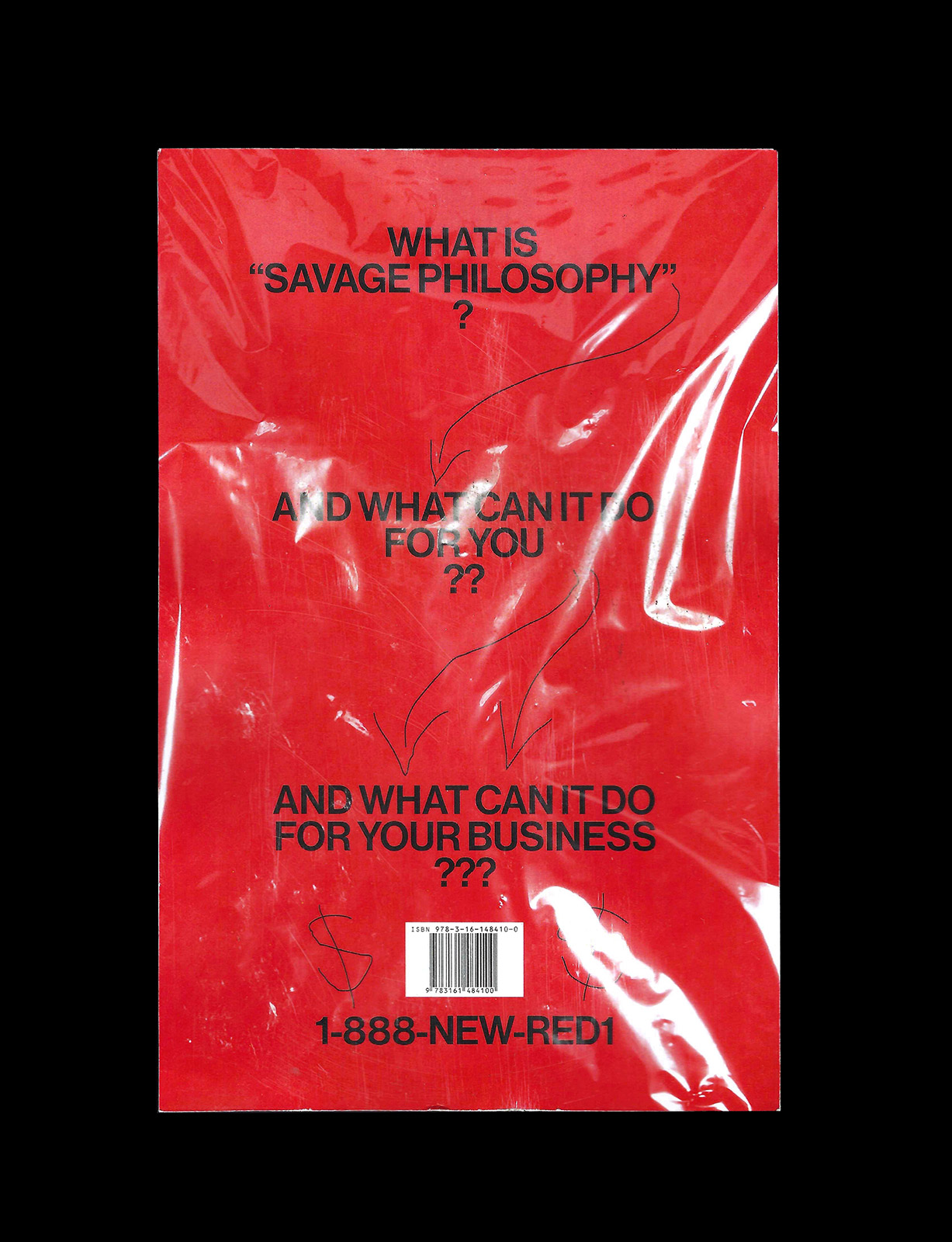

Jackson Polys, Adam Khalil, and Zach Khalil comprise this public secret society, alongside a circulating crew of collaborators (in all that word’s valances). In the case of these posters, those fellow travelers include Riley Hooker, who entered a “brain melding” with the trio to create the quasi-ads, as well as Dylan Clancy, who worked on the spot illustrations. “I feel like something funny happens because a lot of our collaborators are non-native,” says Adam Khalil. “There’s always this moment of hesitation on their part, like, ‘Wait, can I actually do this?’ This collaborative play makes a safe space for unsafe ideas.” These unsafe ideas involve not only exploring the taboos around representations of Indigenous people by settlers (that white guy you see in many of the posters, as well as in other NRO works, is Jim Fletcher, who previously impersonated American Indians on stage)—but also the project that the 1-888 number asks you to participate in: returning North American land to the descendants of its original inhabitants and stewards.

New Red Order’s art, not despite but precisely through its humor and aestheticization, works to bring this land-back proposition about. In The World’s UnFair, a public installation comissioned by Creative Time and staged outdoors in Long Island City this past fall, the collective created a counterpoint to the namesake exhibitions which often exploited Native people. Post-Disney, the UnFair featured an animatronic beaver and all. But in addition to these sculptural interventions, New Red Order created videos and installations that showcased real-life examples of people who voluntarily returned their land, or money derived from it, to Indigenous communities.

As the collective—with its collaborators—is ever-changing by getting non-natives to turn coats into “informants,” NRO is likewise formally voracious: deploying the vernaculars of advertising and amusement parks, yes, but also documentaries, streetwear, recruitment centers, installations, or, as shown at major venues like the Sharjah Biennial and the Museum of Modern Art, photogrammetry videos that turn sculptures of exponents of the US’s westward expansion into fleshy, uncanny, unnerving 3D renders.

“It acknoweldges that the reality that we’re all inheriting is perversely funny in its ridiculousness. From 1492 to today is a series of missteps that have led us into this moment.”

Tracing a legacy that merges culture jamming and the readymade within the context of contemporary art, Khalil explains that the visually diverse work is in part an “acknowledgment that the absurdity of the reality we’re inheriting is actually maybe enough.” Thus this art—which lives beyond institutions as films, hotlines, billboards, public spectacles, and wheatpastes—appropriates familiar aesthetics as “Trojan horses” which “allow the audience to see the world in a different way.” Polys takes it a step further: If the readymade originates contemporary art, per some thinkers, this means anything can be the found object turned art—a urinal, sure, but even settler colonialism itself. “With that realization, anything is possible,” he says, “and moving as a public secret society, we have to raise visibility, so we have to work with the tropes of publicity and advertorial frameworks.”

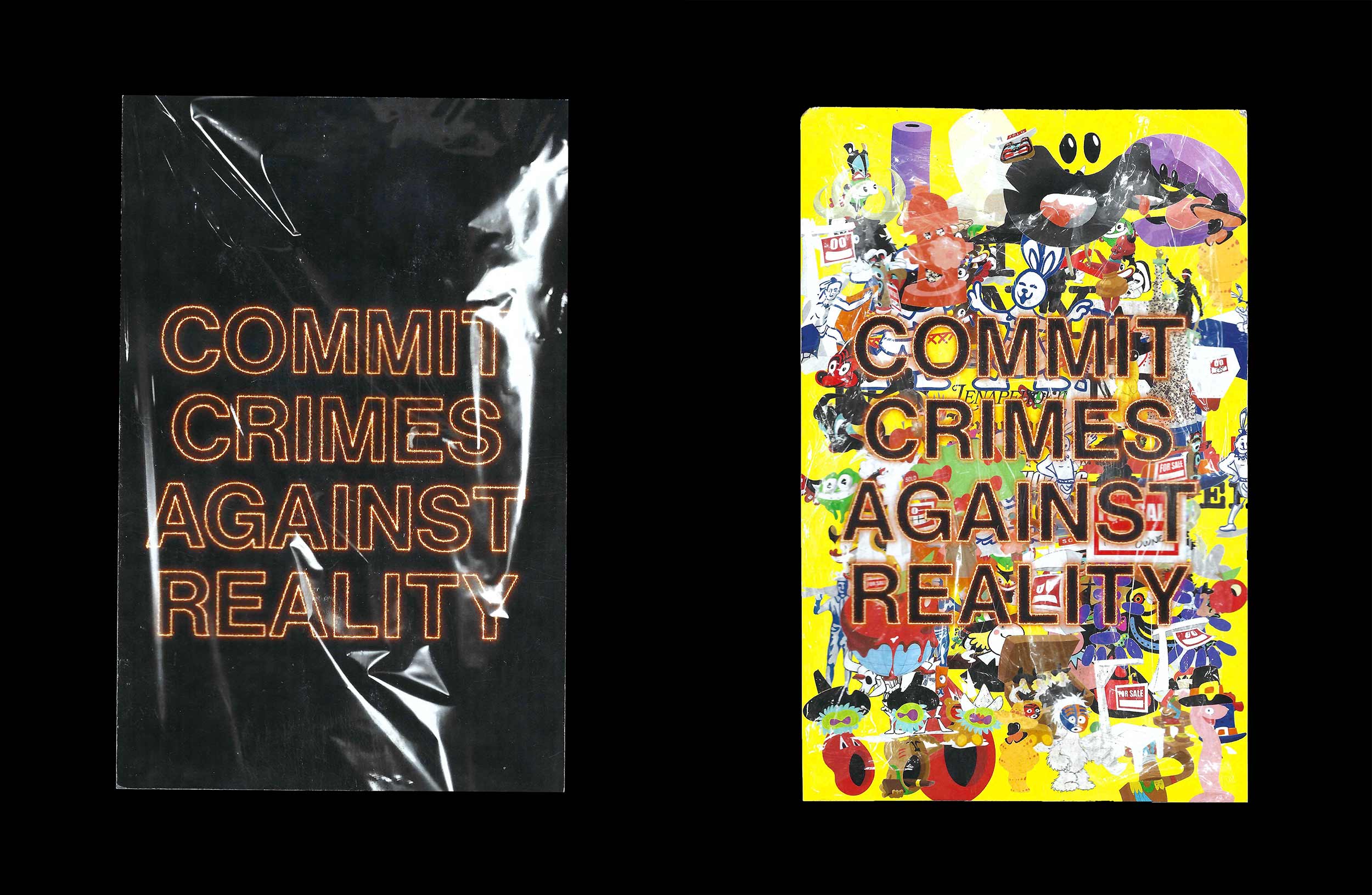

“COMMIT CRIMES AGAINST REALITY” commands one poster. If Polys is correct about settler colonialism being a readymade, Khalil riffs, then perhaps that’s from where the dark humor so prevalent in NRO’s work emerges. “It acknoweldges that the reality that we’re all inheriting is perversely funny in its ridiculousness. From 1492 to today is a series of missteps that have led us into this moment.” But with the awareness of what’s come before—planted in people’s minds with disarming, sly art—we settlers can see those missteps more clearly, and, starting today, give it back.