The artist and filmmaker joins Whitney Mallett, founding editor of ‘The Whitney Review’ to discuss the artifice of authorship through her alter-ego Val

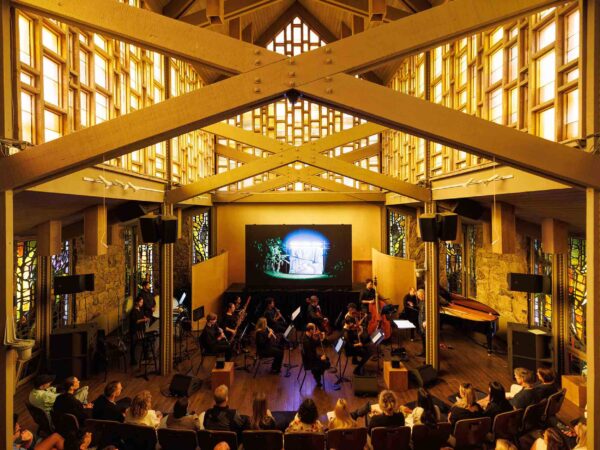

When Mara Mckevitt played Val, she wore a blonde wig, red lipstick, and didn’t show her teeth. This persona Mckevitt invented was just an email address at first. Val was ostensibly a video artist who’d employed Mckevitt as her assistant, but Val was, in fact, Mckevitt’s own invention. Eventually Mckevitt started animating the persona—socializing at gallery openings or taking meetings to discuss potential commissions. Mckevitt would wear the blond wig and perform the character of Val herself. There’s a study of workplace dynamics at the center of the project. When I texted Mckevitt, “It really kills me you were pretending to be your own boss,” she replied, “lol aren’t we all!!!” As the project grew, other performers portrayed Val too. Emily Allan plays her in Mckevitt’s short film, Val, the New York premiere of which my publication The Whitney Review is presenting at Metrograph on May 25. (We’re doing a talkback after too, so consider this both shameless plug and preview.)

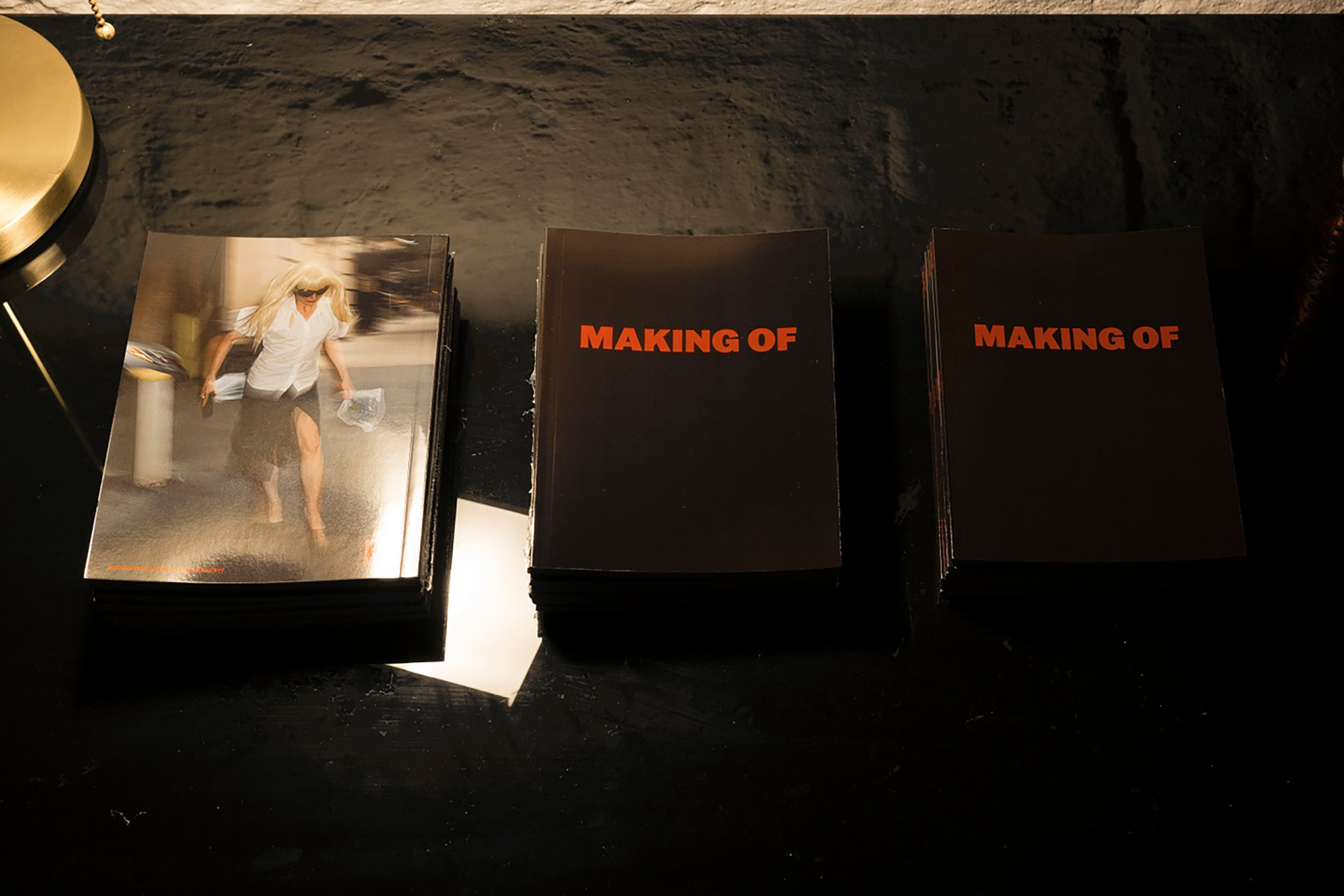

Val might bring to mind popular persona projects like Sasha Fierce or Chris Gaines, but its closest predecessor is Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Roberta Breitmore, an ongoing performance series. The now 83-year-old artist’s first act as Roberta Breitmore came in 1973, when she checked into a hotel under her alter ego’s name. In the following years, Roberta’s activities expanded and included opening a bank account, obtaining credit cards, renting an apartment, seeing a psychiatrist, and joining Weight Watchers. Like with Mckevitt’s Val, Roberta developed her own mannerisms. Hershman Leeson initially played the character herself, but a few years into the project, she sought other performers to take on the guise of Ms. Breitmore. Initially Val was a performance piece Mckevitt was staging in private, the people she was interacting with as “Val” were mostly unaware there was even a performance going on. It developed, however, into the short film Val and the book Making Of (both completed in 2023). The slim 64-page autofiction text published by the Cologne gallery Clementin Seedorf chronicles the project’s origin story and production, including how Mckevitt raised funds. Making Of operates as a kind of control center for the whole body of work but the urtext is the script for the film,” Mckevitt explained.

In the film, shot by Sean Price Williams, Mckevitt does double duty as director and actress, playing Mara, the brunette, while her co-star, Allan (“She’s our generation’s Tilda,” Mckevitt contends) plays Val, the blonde. The two tussle over an external hard drive containing moving-image files. It’s a video artist’s fantasy that .mp4s could operate as a macguffin the way we expect a duffel bag of cash to compel a fight scene with dramatic gravitas. The fetishistic dimensions of this fantasy are keyed up as the film is also beat-for-beat reminiscent of porn.

If there wasn’t already enough that’s-so-meta symbiopsychotaxiplasm going on, brace yourself, because there are more layers to this thing! The alleged backstory behind the production—as reported in Making Of—includes Mckevitt’s working relationship with a character named Sophia. As Mara and Sophia provide companion services, which allow Mckevitt the financial windfall to fund Val, the narrator questions the blurry line between what’s genuine and what’s performative when it comes to how she feels about Sophia. There’s a tenderness to the story of their friendship, while at the same time, Mckevitt’s auto-fictional introspection ratchets up the sheer absurdity of it all—and not just for the events rendered on the page. Mckevitt cuts to the heart of these interactions, confronting us with the different ways we fake it in our own lives. Long after you’ve put the book down, a sense of destabilization just might bleed into how you see your own contracts and relationships. That’s what happened to me, anyway.

Val’s New York premiere finds the film in conversation with two other feats of deadpan cinema: Catherine (2014), starring Jenny Slate, also set in an office, and The Amateurist (1998), directed by and starring Miranda July. When July saw Mckevitt’s film, she said, “I think I already made something for you,” suggesting it’d be generative to have the two films in conversation. In The Amateurist, July directs a version of herself in a wig, static and delay meditating her proxy’s performance on a screen within the screen. It complements parts in Mckevitt’s film where Alicia Novella Vasquez’s character, the remote super-boss of both Mara and Val, appears on a Zoom-esque conference call.

I met up with Mckevitt at her apartment for coffee while her cat named Audio napped nearby to chat about both Val and Making Of.

Whitney Mallett: So your book is called Making Of and on one level it’s the ‘real story,’ catering for our desire for the ‘behind-the-scenes.’

Mara Mckevitt: Which is why people often stay for the Q&A after a film screening. Or why I might watch a documentary about the making of Fitzcarraldo. I feel like I’m getting the ‘real’ situation. It demands authenticity, and in a way, mandates it.

Whitney: But then you’re also playing with our expectation or desire for authenticity, right?

Mara: And my own desire for it! I would love to be an authentic subject, but I don’t think that’s possible. I don’t know if authenticity is even, like, a stable category. When those meme trends erupted like ‘main character syndrome’ and ‘my life is a movie,’ I felt it was proof that no one is necessarily invested in the idea that the self is something real. [Instead, people see] that it is something fabricated for dramatic potential. I think we have some consensus that the self is the most fictitious production, but it doesn’t mean that I am not seduced by the possibility of authenticity.

Whitney: When you conceived of these two interconnected works, the film Val and the book Making Of, did you imagine having any control over which order people might consume them in?

Mara: It didn’t occur to me that I would ever have that control. But I have always been interested in the rule that you should read the book version of something first in order to experience your own cinematic adaptation in your mind before submitting to someone else’s imagining of it. Making Of is based on the production of the short film Val and the short film Val is based on my performance playing the artist Val, who I made up. There’s no coherent order because each form contaminates the other. Making Of operates as a kind of control center for the whole body of work but the urtext is the script for the film.

Whitney: I started with the book, and when the book begins, you’re working as an artist assistant. And eventually this boss of yours inspires the character of Val.

Mara: Val was designed as a sort of matrix of bosses.

Whitney: So you’re playing Val, and you’re also playing Mara, her assistant. You’re recreating the artist-assistant dynamic you had with your former boss but now you’re playing both roles.

Mara: At the beginning, Val was an email address. So she was more of a location before she became a person. Knowingly or not, I think the inception was haunted by Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Animating Val came gradually over time. She would then end up as the author of the work I was making which ultimately recreated the artist-assistant dynamic where you become perhaps too involved in an artwork that you did not ‘make’ which I think is one of the more literal expressions available of authorship-as-sham. And regardless of this dynamic, I don’t believe that anything I’ve made is independent from what I’ve consumed.

Whitney: And you were legit interacting with people this way?

Mara: Yeah, like ‘Val’ directed a shoot starring Monica Mirabile and Sigrid Lauren which wound up becoming a sort of diorama for what would become Val, the short film. During pre-production, they had met me in the role of Val’s assistant. During Zoom calls I was often apologizing for Val’s absence, assuring them that she was really excited about the project.

“It’s not good enough today to just create good discrete cultural objects—you have to perform the role of the author.”

Whitney: It’s cool to me that you were playing the submissive in a larger universe you had control over. This is something I’m always in awe of my grandmother for.

Mara: I was not prepared for you to say ‘my grandmother.’

Whitney: [Laughs] A couple of years ago she became the president of her volunteer organization, and she was always telling me how she would pretend she didn’t know something to get someone to do what she wanted or make her life easier in some way. Strategic humility. This is something me and my mother are, like, incapable of doing. We’re both such know-it-alls. We need you to know we know.

Mara: The process was a big exercise in not knowing what I was doing and still doing it. If I know exactly what I’m going to make, I’m skeptical of my motivations. If I’ve turned over the rock and I’m just showing you the underside of the rock, this is not that fun.

Whitney: You’re not going to surprise yourself and you’re not going to learn anything.

Mara: No, I’m probably not going to learn anything about myself or other people. And I think that’s the fun part. I thought Val could be a sort of toy for me that I could use to avoid all of the seemingly obligatory marketing of the self. And it was embarrassing to be really wrong about that. Like the joke was on me almost immediately. So then I just doubled down, and submitted to what was likely the Freudian repetition compulsion thing.

Whitney: It feels very relevant and insightful to our times, because it’s not good enough today to just create good discrete cultural objects—you have to perform the role of the author. The meta narrative that the artist sits in in the social media marketing landscape is, unfortunately, arguably more important than the actual work. This is frustrating! People seem to be rewarded for it more than focusing on craft. But I feel like what you’ve done is craft a really strong book and film, which then comment on this reality.

Mara: Right, and I think about artists who have ‘opted out’ or refused to participate in the culture industry in certain ways: artists who won’t be photographed, won’t go to openings, who refuse interviews, who abstain from the marketing of personhood, or whatever. And I wonder if at this point, absence or withholding is actually just a market decision—and one that maps on perfectly to the ‘scarcity drives demand’ rule. Like, I think instituting an austerity operation around Val would have been fine but the tenuousness of authorship, performance, documentation, revisionist history… these were more interesting subjects to me than launching an outright personality blackout on myself. If I was going to completely, you know, irreversibly withdraw, go off grid, etc., and just operate entirely through Val in very clandestine terms, it may not have allowed me to actually create a situation in which Person A has an exchange with Val as a discrete entity; Person B has some indication that Val is a project of mine; Person C meets Val, an artist who wants to shoot them; Person D knows about Val through Mara referring regularly to her boss; Person E interviews Val for a news story and there is no Mara at all. I wanted to see what would come from all of these different stories piled up like a car crash.

“I think erotic labor is mandated within all types of work, and so is this element of performing authenticity.”

Whitney: It’s complicated, but I’ll say you establish these dynamics very lucidly and quickly, in an economy of pages. And it gets even more complicated than what we’ve even talked about in this interview so far. Because to fund the film about Mara and Val, you start working with Sophia and that’s another doubling, proxy dynamic. By the time the film is made, are Mara and Val also informed by the relationality of Mara and Sophia?

Mara: I think what prompted me to write the book was feeling almost body-checked by the production itself. In the story, making Val’s character creates a job that prompts the performance of Val, necessitating the death of Val, which is expensive and can only be paid for through a deeply complicated and at times incoherent relationship between two other characters: Sophia and Jack. The final act, so to speak, is hiring Emily (based on Emily Allan who plays Val in the film) as an acting coach to teach me how to act as myself—an allegorical exercise as well as a practical one.

Whitney: I liked that Maya [Martinez]’s review of Making Of in The Whitney Review focused on the role of the magician versus the filmmaker, the shared desire to suspend disbelief and the contracts we sign to enter into a given illusion.

Mara: I think so many of us are writing and signing these contracts all day long, suspending and, to some extent, stretching this function to its limit. I often trick myself in order to do things.

Whitney: I also really appreciate how sex work features in the narrative. It’s integral to the material orchestration of these events, but not the central focus.

Mara: I think erotic labor is mandated within all types of work, and so is this element of performing authenticity.

Whitney: You’ve used the word authenticity again. What do you think of the difference between authenticity and sincerity?

Mara: Authenticity registers as an image-heavy thing, and sincerity is a feelings-oriented experience.

Whitney: Yeah, I agree. Authenticity is like fake news. Sincerity is more affect. You wouldn’t say that news story or that paparazzi photo is sincere or insincere. I almost feel like sincerity is 19th century and authenticity is 21st.

Mara: Everyone’s sort of fucking the corpse of authenticity, right? Gideon Jacobs refers to this moment as ‘the Authenticity Wars.’ Like, everyone is clamoring to identify it, blow its cover, copy it, destroy it, and this is likely in part due to its disfiguration via liberal consumer identity. The moment I start to wonder if I’m doing something in an authentic way, I feel I’ve trapped myself in a funhouse. But there are other questions that are more generative. Why am I doing this? What is motivating these decisions? And some of us want to be deceived and do a lot of work to stay in deception. I often find myself in situations where I am moved and manipulated, and am ok with that. I like movies because I want to be convinced and coerced.

“Popular workplace fantasies include fucking your boss or killing your boss. This felt like a sort of natural extension of how renderings of sex and violence are, at the level of choreography, almost interchangeable in mainstream movies.”

Whitney: To be a little stupid for a second, Val feels like a boy movie. As much as it’s about best friends and sex work, it is not girly in the expected ways. It’s more reminiscent of David Fincher’s The Game [1997] and Fight Club [1999].

Mara: I think Val’s architecture is a fantasy around the market value of media. Logically speaking, there isn’t really a situation in which media or information or anything that you could put on a hard drive would present so much dramatic potential, that there would be a physical fight over the drive. It’s not a suitcase full of cash. And maybe the more zoomed-out view of this is underscored ubiquity of content, which we’re expected to make and disperse for free on a regular basis, streaming culture, AI-generated feature films… this is not a world in which you can convince many people of the value of media—of video in particular. The role of video in the art world… It’s hard to sell because it is infinitely reproducible, making the reason to own it very abstract.

Whitney: Without being X-rated, Val somehow feels like a porn. I think?

Mara: Beat for beat, it does behave like an office porn. The dominant character is always entering the space, while the submissive one might as well be part of the furniture. There’s a shrill or otherwise slightly exaggerated conflict. Aside from incest scenarios, work situations make up a significant portion of porn videos. Is that because we spend most of our time at work and therefore it is the most available screen to project sexual fantasy onto? Is it an easily digestible power relationship? Popular workplace fantasies include fucking your boss or killing your boss. This felt like a sort of natural extension of how renderings of sex and violence are, at the level of choreography, almost interchangeable in mainstream movies. Looking back, the choreography felt more conflict-ridden and the fight preparation and formulation felt more erotic.

Whitney: You’re referencing all the references. Sex and violence are typically less referencing the real thing and more self-reflexively referencing visual culture’s representation of the thing. I thought of the word they use to describe the relationship between reality and fiction in the WWE, kayfabe.

Mara: I feel like anytime I watch a fight scene, I could be watching a sex scene. And every time I watch a sex scene, I might as well be watching a fight.